- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This newly revised and expanded second edition of The Soviet Union Today provides a comprehensive introduction to contemporary Soviet reality. Written by thirty experts, the book is divided into eight general sections: history, politics, the armed forces, the physical context, the economy, science and technology, culture, and society. The individual chapters, which are intended to respond to the questions most frequently asked about the Soviet Union, are devoted to everything from the Lenin cult to the KGB; from Soviet architecture to Soviet education; from the status of women and ethnic minorities to the question of religion. All of the chapters from the first edition have been updated, and five new chapters—on the Soviet cinema, mass media, foreign trade, arms control, and the legal system—have been added. An annotated list of further reading suggestions and a special "Note for Travelers" enhance this volume's usefulness. Students, teachers, journalists, prospective tourists, and anyone interested in Soviet life will find this new edition of The Soviet Union Today an essential and stimulating guide to understanding the world's largest country.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226116631, 9780226116617eBook ISBN

9780226226286SOCIETY

The authors of this final section of the book discuss various of the more urgent questions raised by a survey of Soviet society today. Ralph S. Clem, in describing its complex ethnic structure, points out the many problems it has in common with other multi-ethnic societies and reaches the perhaps surprising conclusion that, on the whole, Soviet rule has strengthened the position of the ethnic minorities. The current state of religion is the subject of Paul A. Lucey’s essay, which, like the chapter preceding it, abounds in facts not readily available elsewhere. Readers may again be surprised to learn that at least 30 percent of the Soviet population are practicing believers—not as high a proportion as in the United States, to be sure, but considerably higher than in many other Western societies. Mary Ellen Fischer then raises “the woman question”—not just the legal rights and status of Soviet women but the actualities of their situation with respect to both the unfulfilled promises of the past and their future prospects. And Peter B. Maggs, in explaining the workings of Soviet law, provides numerous insights into Soviet society in the larger compass.

In the final chapter of the book, David E. Powell reminds us of the traumatic history of Soviet society; points to the generally beneficial nature, until recently, of social change in the Soviet Union; and expands on certain ominous developments in Soviet society today. His essay may be read as a detailed summary of points raised in various earlier chapters. The picture to emerge is one of a troubled society, its heroic—or tragic—age behind it, its future uncertain. But Powell also notes that much of what he discusses is endemic in modern life. It is right that this book should conclude with a reminder of our common humanity.

26

Ethnicity

RALPH S. CLEM

On April 14, 1978, several thousand people took to the streets of Tbilisi, the capital of the Georgian Republic of the Soviet Union, in protest against changes in the republic’s constitution that would have downgraded the official status of the Georgian language. The next day, the authorities canceled the proposed revisions and restored the indigenous tongue to its privileged position.1 The significance of this event, probably not fully appreciated in the West, lies in its dramatic illustration of the salient aspect of contemporary Soviet reality: that the Soviet Union is an ethnically diverse state, one in which all of the problems common to multi-ethnic countries manifest themselves. If one wishes to understand the forces shaping Soviet society, therefore, the nature and role of ethnicity is a prime consideration.

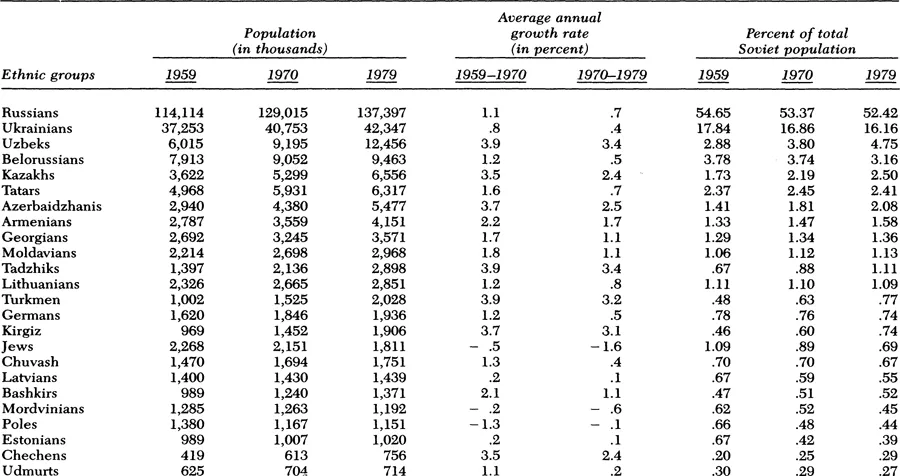

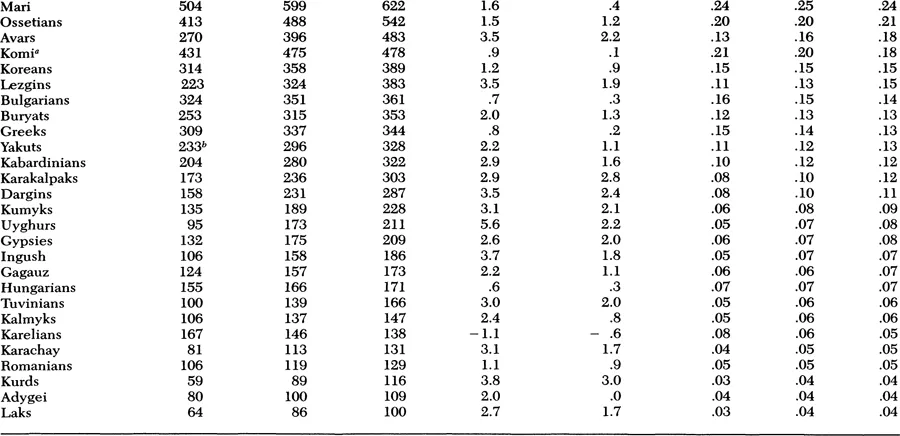

The Soviet Union is one of the world’s most ethnically heterogeneous countries in terms both of the number of ethnic groups and of their respective sociocultural characteristics. The population of the country comprises some 100 separate ethnic groups—or nationalities, in Soviet parlance—among which is to be found an extraordinary variety of languages, religions, phenotypes, and the other attributes, tangible and intangible, of ethnic identity. The Russians are by far the largest such group numerically, accounting for just over half the country’s population. Minority groups range from several tens of millions to several thousands (see table).

This remarkable assemblage of peoples is the result of a historical process of territorial expansion that lasted for about four centuries. During this period the Russians moved out in all directions from their ethnic hearth in the northwestern part of what is today the Soviet Union to take over neighboring lands inhabited by non-Russians. The empire of the last century was formed, in other words, through the addition of non-Russian territory to the Russian core; and the present Soviet state is, geographically, almost identical to its tsarist predecessor.

POPULATION OF MAJOR SOVIET ETHNIC GROUPS

Sources: 1959 and 1970 figures from Tsentral’noe Statisticheskoe Upravlenie, Itogi Vsesoiuznoi Perepisi Naseleniia 1970 goda (Moscow: Statistika, 1973) IV, pp. 9–11; 1979 figures from Tsentral’noe Statischeskoe Upravlenie, Naselenie SSSR (Moscow: Politicheskaia Literatura, 1980), pp. 23-26.

aFigure for Komi includes Komi-Permyaki.

bThe number of Yakuts was reported as 236,655 in the 1959 census itself.

Two key elements of the present ethnic situation derive from the manner in which the state took shape spatially. First, it is generally the case that the periphery of the Soviet Union is ethnically non-Russian territory whereas the Russian homeland is geographically the center, a situation fraught with obvious geopolitical significance. Non-Russian lands extend in a vast arc from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the northwest (Estonia, Latvia, and Luthuania); south along the western border (Belorussia, Ukraine, and Moldavia); east across the Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaidzhan); on to Central Asia (the areas inhabited by Turkmen, Uzbeks, Tadzhiks, and Kirgiz) and the Kazakh steppe; and, finally, across Asia to the Pacific Ocean (homelands of the Buryats, Tuvinians, Altays, Khakas, and other peoples). Sharpening this Russian/non-Russian, center/periphery dichotomy are several irredentist situations in which members of the same ethnic group live on both sides of the Soviet border, as in the case of the Finnish Karelians, much of whose homeland was incorporated into the Soviet Union in World War II.

Second, in spite of the proliferation of ethnic Russians in all regions of the country, the other Soviet peoples are still usually concentrated in their ancestral homelands. Thus, ethnicity, in the Soviet context, has a territorial aspect that differentiates it in some degree from multi-ethnic societies that evolved through immigration. Furthermore, the Soviet Union is structured administratively as a federation of 15 nominally independent units (union republics), each of which is officially the homeland of a major national group. Smaller nationalities and some of the larger ethnic groups with homelands in the interior (where even nominal independence would be an obvious fiction) are recognized administratively by lower-level units of various types. All told, there are 53 ethnically defined political-administrative units in the Soviet Union, representing over half of all Soviet national groups.

Given this complex ethnic structure, it is imperative to investigate ethnicity with respect to Soviet history, contemporary reality, and the future of the “Union” itself. Unfortunately, in spite of the increasing number of relevant works appearing in the Soviet Union and in the West, and even though the best of them are insightful and factually informative, our understanding of Soviet society in general and of ethnicity in particular has been hampered by an approach to societal phenomena in that country that regards them as basically unique. This particularistic approach, it should be stressed, has generally been adhered to on both sides of the ideological divide.

Thus, Soviet scholars almost always adhere to the Marxist view that social dynamics—including ethnic group relations—are determined by the nature of the specific economic system, and they therefore maintain that societies based on a socialist economy will be inherently different from capitalist societies. Any cross-system similarities in social trends are dismissed by Soviet scholars as superficial and ephemeral.

In the West, on the other hand, comparative research in the social sciences has long been hampered by an unscientific tradition that holds that societal traits are unique to time and place and not amenable to broad generalizations because of cultural conditioning and human unpredictability. Moreover, as Robert Lewis has noted, Western scholars have attributed a uniqueness to Soviet society on the assumption that a “totalitarian” state is capable of decisively controlling basic social processes.2 If a government could actually regulate, with even moderate success, such aspects of human behavior as migration, then a fundamental difference would indeed exist between totalitarian states and those in the West, where social trends are, in effect, the summation of myriad individual actions. A difference of that kind would then rule out the use of models derived from Western experience in explaining social change in the Soviet Union.

Partly as a consequence of this attitude we in the West have tended to impute to Soviet society a distinctiveness that is not usually warranted by the facts. It seems clear enough that, so far as ethnicity is concerned, today’s Soviet Union has much more in common with other multi-ethnic societies than not. If we consider the ethnically related troubles in such Western states as Belgium, Canada, Spain, and the United States, it will come as no surprise that bilingualism, assimilation, ethnic intermarriage, affirmative action, regional autonomy, a shifting composition of the population along ethnic lines, and the geographical mixing of ethnic groups through migration are all contentious issues in the multi-ethnic Soviet Union as well.

Language is perhaps the most sensitive of these issues, especially the role and status of the official lingua franca, Russian, in relation to the various non-Russian tongues. The importance of this issue derives in part from the overtly ethno-symbolic quality of language, in part from the belief among scholars, both Western and Soviet, that the increasingly widespread use of Russian by non-Russians presages a loss of ethnic identity—or ethnic assimilation. And the most serious aspect of the issue concerns the use of Russian in education, whether as the medium of instruction or as the object of separate study.

Following the advent of Soviet rule, the network of indigenous language schools in the various national homelands was greatly expanded. Yet considerable variation exists today in the degree to which the non-Russian tongues are in fact an integral part of the school system. The use of non-Russian languages as the medium of instruction differs from group to group, with some nationalities granted much more extensive rights than others. These rights are tied to the ranking of the ethnic territories in the federal hierarchy. Students who are members of numerically larger ethnic groups can receive native-language instruction throughout secondary school and, in some cases, at the university as well (although the selection of courses available in the vernacular may be limited). Those from smaller nationalities may only be able to attend school in their own language in the primary grades, if that.

Another facet of this question is the choice available to parents. Schools in which Russian is the medium of instruction have been established in all of the non-Russian ethno-territories in addition to native-language schools, leaving parents of any nationality the choice of sending their children to either type of school. Until 1958, however, children were required to study Russian in the native-language schools and the local language in the Russian-language schools. Then the Soviet government promulgated a set of educational reforms, one of which made the study of languages other than the medium of instruction voluntary rather than mandatory. This led to some hostility and resistance among several of the largest non-Russian ethnic groups, apparently out of fear that non-Russian students in Russian-language schools would abandon non-Russian language courses. This move was also seen by some in the West as further evidence that the Soviet authorities were attempting to accelerate the process of ethnic homogenization or Russification.

If the Soviet government has been actively promoting the formal adoption of Russian as one’s “native tongue” by non-Russians, it has not had much apparent success. The 1979 Soviet census revealed that only about 13 percent of the non-Russian population considered Russian their native tongue; the comparable figure was 10.8 percent in 1959 and 11.5 percent in 1970. At the same time, 49 percent of all non-Russians said that they had a fluent command of Russian as a second language, which represents a major increase, even since 1970, when the comparable figure was 37 percent. These and other linguistic data indicate a growing trend toward bilingualism among the non-Russian ethnic minorities. The number of Russians who speak another language remains quite small, however.

Brian Silver has suggested that whereas the influence of social change (urbanization, higher levels of education, and a greater frequency of inter-ethnic contact) has had the effect of promoting the use of Russian, retention of the non-Russian tongues has been perpetuated by the maintenance of the native-language schools and by extensive use of these languages in the media.3 In short, allowing for differences among nationalities and especially between generations (today’s young people tend to have a higher level of Russian fluency and to be less faithful to their native tongue), the ethnic minorities certainly are not yet disappearing linguistically.

Another way of judging the extent to which ethnic homogenization has taken place in the Soviet Union is to look at the frequency of intermarriage. Given the taboos generally associated with this subject, it is not surprising that among the non-Russian peoples of the Soviet Union there is a consistently high level of in-group marriage (endogamy). The major work on this subject, based on 1969 data from 14 of the large non-Russian nationalities, shows that in no case did the level of those marrying endogamously drop below 82 percent and that for nine of the 14 groups the percentage of endogamous marriages was over 92.4 Even when demographic and sociocultural factors are taken into account, the impression remains that ethnic attachments are sufficiently strong to condition significantly the choice of a marriage partner—this in spite of the fact that the Soviet government views exogamy as “progressive.”

Inasmuch as linguistic Russification and the incidence of exogamy have been relatively limited in scope, we may suppose that ethnic reidentification—or assimilation—has been similarly insignificant. While recognizing that it is extremely difficult to measure assimilation empirically, one study put the total number of non-Russians who from 1926 to 1970 assumed a Russian identity at between 4 and 6 million or about 2 percent of the 1970 population.5 The vast majority of those assimilated were Ukrainians and Belorussians, who are linguistically and culturally akin to the Russians. A few other groups—Karelians, Mordvinians, Germans, and Jews among them—accounted for almost all of the balance. Among most Soviet ethnic groups, therefore, assimilation is virtually unknown.

Sociologist Daniel Bell points to several key aspects of ethnicity that account for its salience and persistence in the contemporary world and are directly relevant to the Soviet situation.6 The first of these is the politicization of ethnicity, wherein the proliferation of the power of the state forces people to rely on ethnic groups as a means of bringing pressure to bear on the system. The Soviet “revolution from above” made it obvious to all where the center of power was and established the state as the focus for any claims to be made by ethnic groups. As Glazer and Moynihan put it, the Soviet state is obviously “the direct arbiter of economic well-being.”7 The ethnic group turns out to be an ideal vehicle for exacting concessions from the state, as Bell noted, because it combines an interest-group function with an affective tie. Furthermore, the Soviet regime has done much to legitimate this approach, since it insists on labeling individuals ethnically and has acted (perhaps not always deliberately) to stimulate ethnic awareness in a variety of ways.

By far the most important sanctioning of ethnicity in the Soviet Union lies in the very political structure of the state. The creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a federation of ethnic territories has been viewed as a clever solution to the problem of disintegration inherent in multi-ethnic countries, a problem of immediate concern in the early years of Soviet power.8 Ethnic autonomy, as represented in the elaborate treaty arrangements binding the ethnic units to the Union, was plainly a tactical political concession, probably thought to be temporary. Yet by formalizing the ethnic configuration of the state, Lenin and his successors provided what turned out to be a lasting, legitimate focus of national aspirations. It could be argued, then, that what was viewed by some as a shrewd manuever and a fraud has instead proved to be a means whereby ethnic group interests, such as education and native-language rights, can be safeguarded and appropriate demands can be made on the state.

Moreover, because the ethno-territorial link was and is legally explicit, the regions have become the instruments for attaining the central goal of Soviet policy toward the nationalities: the approximate equalization of levels of socioeconomic development among them. The government has had some notable successes in this respect, in education and public health, for instance. But the following three interconnected factors have impeded further progress and are likely to continue to do so.

• As do most countries, the Soviet Union has its economic “problem regions.” Owing to the geographically unequal distribution of natural resources, the exigencies of war and strategic considerations, and the pressing need to optimize scarce investment capital, some areas remain relatively backward.9 Since ethnic groups are usually found mainly in their respective homelands, those groups inhabiting the backward regions will be relatively disadvantaged.

• A second reason for the failure to close the inter-ethnic development gap has been the proliferation of Russians throughout the Soviet Union. Unfavorable economic and social conditions, particularly in the rural areas of their own ethnic territory, provided the impetus for the out-migration of millions of Russians to other parts of the country, including the non-Russian lands, where their number rose from 6.2 million in 1926 to 23.9 million in 1979. The vast majority of these Russian migrants settled in urban areas and in many instances took the better jobs, thereby foreclosing opportunities for upward mobility by the local inhabitants. Once a Russian presence is established it takes on an inertial character, since a large Russian population in a non-Russian area provides the linguistic and cultural atmosphere attractive to other Russian migrants.

• The third and potentially most troublesome factor is the striking inter-ethnic variation in population growth (see table). Broadly speaking, the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- History

- Politics

- The Armed Forces

- The Physical Context

- The Economy

- Science and Technology

- Culture

- Society

- Further Reading Suggestions

- A Note for Travelers

- Authors

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Soviet Union Today by James Cracraft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.