eBook - ePub

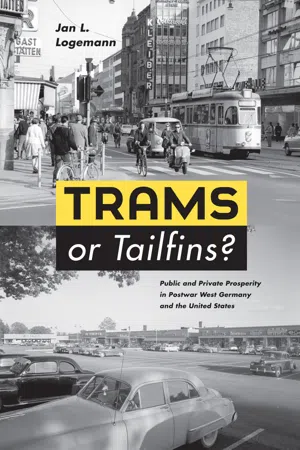

Trams or Tailfins?

Public and Private Prosperity in Postwar West Germany and the United States

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trams or Tailfins?

Public and Private Prosperity in Postwar West Germany and the United States

About this book

In the years that followed World War II, both the United States and the newly formed West German republic had an opportunity to remake their economies. Since then, much has been made of a supposed "Americanization" of European consumer societies—in Germany and elsewhere. Arguing against these foggy notions, Jan L. Logemann takes a comparative look at the development of postwar mass consumption in West Germany and the United States and the emergence of discrete consumer modernities.

In Trams or Tailfins?, Logemann explains how the decisions made at this crucial time helped to define both of these economic superpowers in the second half of the twentieth century. While Americans splurged on private cars and bought goods on credit in suburban shopping malls, Germans rebuilt public transit and developed pedestrian shopping streets in their city centers—choices that continue to shape the quality and character of life decades later. Outlining the abundant differences in the structures of consumer society, consumer habits, and the role of public consumption in these countries, Logemann reveals the many subtle ways that the spheres of government, society, and physical space define how we live.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trams or Tailfins? by Jan L. Logemann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

State—Private Consumption and the Framework of Public Policy

The state has been a central force in shaping modern consumer societies: private consumption has always been framed by public policy. Since the late nineteenth century in particular, the regulation of retail and consumer goods gained in importance as consumers organized politically and the “standard of living” became a focus of wage and price policies.1 While the political debates on both sides on the Atlantic frequently dealt with similar problems, the emerging consumer societies in Germany and the United States were embedded in profoundly different political economies—revealed clearly in the years after World War I—which produced distinct patterns of consumer economic regulation and balances between private and public consumption.

While the United States was increasingly geared toward competitive large-scale mass production and distribution of private consumer goods, with very limited state intervention, Germany produced a more “organized” capitalism that saw a great deal of both state and corporate regulation.2 As American industry and consumers rallied around the promise of material abundance through Fordist mass production at ever lower prices, Europeans by and large held on to a consumer society that was shaped by the tastes of the bourgeois elite and centered on small shops and craft production.3

German consumers, far more than Americans, looked to the state to regulate central aspects of everyday consumption and to ensure a basic standard of living.4 During the Weimar years, the German political economy saw an expansion of public consumption in the form of increased welfare as well as expanded social security that grounded citizenship more strongly in social rights than in the United States. While its policies were neither comprehensive nor uncontroversial, the German state was more willing to address standard-of-living questions by means of public redistribution and public consumption.5 On the local level, “municipal socialism” did much to broaden the array of public goods available to consumers, from energy and transportation to housing and cultural entertainment.6

In 1920s America, by contrast, improving the standard of living was primarily left to market forces, while the more regulatory and interventionist state of the Progressive era gave way to welfare capitalist schemes. The private-public welfare state of employer-based health insurance and pension systems that would come to full fruition during the 1950s and ’60s had its roots in the rise of group insurance models during the post–World War I period.7 The American path to raising the consumer’s standard of living was centered on private disposable income. The “pocketbook” politics that emerged in the first decades of the twentieth century focused on the increasing availability of consumer goods at affordable prices.8 A plethora of brand-name goods became nationally available, and advertising copy sought to create a national consumer culture and consumer identities that revolved around the use of consumer products.9

Consumer products became not only more available but also more affordable to Americans by the 1920s. An expansion in the use consumer credit, for one, played a central role in the creation of a broad middle market, which neutralized some existing class-based differences in consumption patterns.10 More fundamentally, however, the American mass production regime, which was in many ways symbolized by Henry Ford’s assembly-line production of the low-price Model T automobile, rested on the promise of higher wages as in Ford’s introduction of the five-dollar workday in 1914. Consumer products thus grew—if unevenly—more affordable to the workers that produced them in the 1920s. While still limited, widely contested, and introduced somewhat haphazardly during the 1920s and ’30s, the postwar compromise around market-organized mass production and mass consumption was prefigured in important ways during the interwar period.11

The American economic model certainly appealed to many Europeans as a vision of cultural democratization and material improvement. Talk of “Americanisms”—the interwar equivalent of “Americanization”—was part and parcel of Weimar public discourse. Numerous aspects of an emerging consumer society could be found in 1920s Germany as well; modern retail structures such as the department store had found their way into the major urban centers of Germany as early as the end of the nineteenth century.12 To many Germans, however, from intellectuals and social elites to industrialists and the vast number of small shopkeepers, the American model also presented a severe challenge. Department stores were at the center of heated public debates—frequently infused with anti-Semitic undertones—about changes in retail structure and the potential consequences to traditional small shopkeepers.13 While small retailers were perhaps no match for chain stores and other American mass distribution retailers of the time, they still wielded enough political clout to challenge American-style mass distribution systems. Producers similarly were often resistant to new forms of marketing-driven strategies and price-driven competition and instead emphasized a traditional focus on quality production in a less competitive “coordinated capitalism.”14 Conservatives decried American “mass” culture as conformist and as a threat to German culture.15 Social Democrats, even if intrigued by the possibility for high wages and expanded consumption under Fordism, nonetheless rejected the limited role of unions and public consumption in the United States.16 Intellectuals on the left, finally, were critical of commercial consumption and the “culture industry,” which appeared to undercut working-class consciousness.

Despite the best efforts of American advertisers venturing on the German market by the 1920s, German attitudes toward consumption did not coalesce with the American mass consumption model.17 The German path to consumer modernity that began to take shape would couch modern consumption within the interests of both social democracy and labor organizations on the left and industry and retailer concerns on the right. Both labor and management, as well as German consumers in general, were ultimately also more likely than their American counterparts to look to the state for regulation of the consumer marketplace.18

The Shared Challenge of the Great Depression

The Great Depression brought questions of mass consumption to the forefront of the political agenda in Germany as in the United States. In New Deal America, the key to overcoming the Depression was eventually seen in expanding consumer purchasing power.19 While strengthening the role of the state in the consumer marketplace and connecting to regulatory traditions of the Progressive era, New Deal policies would ultimately reassert the centrality of private consumption in the American political economy. After 1933, the National Socialist regime in Germany also picked up on the promise of consumer prosperity, projecting its own model of a consumer society as a promise to overcome the social and economic strife of the depression.

The American government exerted unprecedented influence on the consumer market during the New Deal. Several federal programs were aimed at widening consumer markets and ultimately laid the groundwork for the postwar mass consumer society. The New Deal, to be sure, was a disparate set of policies and, especially at the beginning, included a number of regulatory approaches such as restrictive NRA (National Recovery Administration) price policies and AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Administration) price maintenance that ran counter to ideas of promoting growth through mass consumption. What ultimately won the day was a set of policies that aimed at expanding a consumer-oriented marketplace by providing, among other things, plentiful and cheap energy and credit for future growth.20 The creation of Social Security and various public works programs are well-known New Deal efforts to foster domestic purchasing power, but just as integral to the story were agencies such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Federal Loan Administration, or the Tennessee Valley Administration, which promoted infrastructure and credit development. More than just laying the groundwork for the suburban housing boom of later decades, legislation such as the National Housing Act of 1934 provided for the modernization of homes through affordable loans for appliances. Electrification programs, furthermore, drove down utility costs and effectively created mass demand.21 While direct income redistribution (e.g., through taxation) remained limited, public spending within the framework of a capitalist economy became the hallmark of the New Deal and would be taken to new heights during World War II.22

In fighting the Depression over the course of the 1930s and especially after the American entry into the war, consumption became ever more intimately entwined with notions of Americans citizenship and patriotism.23 As purchasing power became the new consensus of liberal New Deal social and economic policy, consumers were expected to wield their power accordingly.24 At the same time, as Lizabeth Cohen contends, the late 1930s saw politically organized and empowered consumers actively engaged in shaping price policies, for example through widespread “buyer’s strikes.”25 The history of postwar mass consumption cannot be written without recourse to New Deal legacies in housing, credit, and energy policy; promoting mass consumption had become a tool of progressive politics. During the New Deal, however, mass consumption was also framed in a political context that harbored at least the possibility for more radical visions of consumer organization and more direct public regulation of the consumer marketplace.

Consumer policies in the wake of the Depression in Nazi Germany have received some attention in recent years as an aspect of the “modernity” of the National Socialist regime.26 While economic policy under the Nazis was not uniformly oriented toward modern notions of economic growth, its promotion of infrastructure did have modernizing effects. Furthermore, many Nazi leaders, recognizing the importance of consumer demand, looked to the mass production of consumer goods as a means to break down social division and garner support among German workers.27 As much as American “materialism” was rejected, industrial leaders and policy makers looked to the United States for technical innovations in the realm of mass production.28

In its rhetoric, Nazi consumer policy had initially focused on the protection of small shopkeepers and craft producers, who counted among the core constituencies of the party. Indeed, the 1930s saw legislative restriction on modern retailing forms such as the department store and consumer cooperatives.29 Even before Hitler’s ascent to power, Nazi-led protests in 1932 had brought legislation curbing the expansion of chain stores. Now the state was stepping up regulation of advertising in an effort to make the consumer marketplace more honest and less competitive.30 These protectionist efforts culminated most dramatically in the attacks on and subsequent “aryanization” of countless Jewish-owned shops and, most importantly, department stores during and after the pogroms of November 1938. Ultimately, the hopes of the small shopkeepers were betrayed as other policies of the regime benefited the growth of ever-larger cartels and modern forms of mass production.

Consumers, after all, were a broader, more attractive constituency than shopkeepers; as the economy began to rebound in the mid-1930s the promise of new forms of consumer goods began to permeate Nazi propaganda. Mass-produced items, from the Volksempfänger (people’s receiver) to the Volkswagen (people’s car), were meant to entice large parts of the population to whom such products had been unavailable before.31 The Nazi leisure organization Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) advertised vacations for working-class Germans, including cruises to such exotic places as Norway and Madeira.32 In Nuremberg, the Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung began to professionalize market research and the study of consumption.33 Housing experts and urban planners began to anticipate modern traffic demands and promoted models of rationalized mass housing production for a consumer market that would transcend the class divisions of earlier decades.34

For all these modernization efforts, the Nazi regime pursued a distinctly “German” model of a modern consumer society. Not only were the promises of consumer prosperity restricted to ethnically German members of the Volksgemeinschaft, but consumption was in many ways subordinate to political and ideological demands. Advertisers were urged to “Germanize” the language and style of their ads. To achieve greater autarchy and independence from imports, the regime pushed “patriotic” German products such as apples in favor of imported citrus fruit.35 Nazi leisure programs were less concerned with individual preferences than with organized group experiences infused with ideological subtexts. As consumer culture was politicized during the 1930s, free consumer choice was limited.

Nazi consumer politics presented postwar West Germany with a mixed legacy. Hartmut Berghoff has aptly char...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Divergent Paths to Mass Consumer Modernity: Comparing West Germany and the United States

- Part 1. State—Private Consumption and the Framework of Public Policy Introduction to Part One

- Part 2. Society—The Social Significance of Consumption Introduction to Part Two

- Part 3. Space—Urban and Suburban Spaces of Consumption Introduction to Part Three

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index