- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the most influential choreographers of the twentieth century, Merce Cunningham is known for introducing chance to dance. Far too often, however, accounts of Cunningham's work have neglected its full scope, focusing on his collaborations with the visionary composer John Cage or insisting that randomness was the singular goal of his choreography. In this book, the first dedicated to the complete arc of Cunningham's career, Carrie Noland brings new insight to this transformative artist's philosophy and work, providing a fresh perspective on his artistic process while exploring aspects of his choreographic practice never studied before.

Examining a rich and previously unseen archive that includes photographs, film footage, and unpublished writing by Cunningham, Noland counters prior understandings of Cunningham's influential embrace of the unintended, demonstrating that Cunningham in fact set limits on the role chance played in his dances. Drawing on Cunningham's written and performed work, Noland reveals that Cunningham introduced variables before the chance procedure was applied and later shaped and modified the chance results. Chapters explore his relation not only to Cage, but also Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, James Joyce, and Bill T. Jones. Ultimately, Noland shows that Cunningham approached movement as more than "movement in itself," and that his work enacted archetypal human dramas. This remarkable book will forever change our appreciation of the choreographer's work and legacy.

Examining a rich and previously unseen archive that includes photographs, film footage, and unpublished writing by Cunningham, Noland counters prior understandings of Cunningham's influential embrace of the unintended, demonstrating that Cunningham in fact set limits on the role chance played in his dances. Drawing on Cunningham's written and performed work, Noland reveals that Cunningham introduced variables before the chance procedure was applied and later shaped and modified the chance results. Chapters explore his relation not only to Cage, but also Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, James Joyce, and Bill T. Jones. Ultimately, Noland shows that Cunningham approached movement as more than "movement in itself," and that his work enacted archetypal human dramas. This remarkable book will forever change our appreciation of the choreographer's work and legacy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

(1)

Recycling the Readymade

Marcel Duchamp and the Rendez-Vous in Walkaround Time

Preservation has always been central to Merce Cunningham’s work. Figuring out how to capture and repeat the steps and phrases he executed in the studio was a preoccupation that generated innovations—not in dance notation, since he never learned or developed a notational system, but rather in compositional technique. Arguably, Cunningham was as interested in processes of recycling as he was in processes of invention.1 He developed a modular approach, which made shorthand notation less cumbersome and allowed for permutation, self-citation, and preservation of the already done. While other variables of the dance production, such as music, lighting, costumes, and décor, might have been out of his hands, in most cases the dancing on stage was fully anticipated, planned down to the last shift of the gaze.

In the face of repeated queries from interviewers and audience members concerning the role of unplanned actions in his dances, Cunningham would respond unequivocally that improvisation was not part of his chance aesthetic. With very few exceptions, dancers were forbidden to improvise. Although at times encouraged to develop their own independent interpretation of the phrasing, they followed a carefully scripted sequence of movements and poses from which they were expected never to deviate. Yet from the beginning, the public confused “chance operations” with “improvisation,” perhaps because both were seen to undermine the authorial function. The term indeterminacy, which John Cage began using in the mid-1950s, increased the confusion of spectators, who assumed that an “indeterminate” work was one in which performers were at liberty to do whatever they chose. But indeterminacy as Cage defined it was never equivalent to improvisation as he defined it.2 A work that is “indeterminate with respect to its performance” gave performers a range of possible actions to execute, but it did not allow unfettered invention.3

It is true that during the 1960s Cunningham experimented with indeterminacy in works such as Field Dances (1963), where he gave each dancer a collection of actions to be performed whenever the dancer was inspired to do so. Intrigued by Judson Dance Theater choreographers, he tested out the effects of incorporating pedestrian movement and performing actual tasks on stage (such as watering a plant in Variations V of 1965).4 But these innovations were quickly abandoned, for it was crucial to Cunningham’s process that a movement, phrase, or entire dance, once set on dancers, be preserved in such a way that it could be repeated. The repeatability of the random was, in fact, a top priority; it might even be said that repeatability, as a quality of the dance itself, was almost as significant as the originality of the sequence achieved by chance means. That is, as opposed to an aesthetics of improvisation, which values procedures that might engender the unrepeatable, Cunningham’s chance aesthetic privileges procedures designed to yield that which can be memorized and retained (even if with difficulty). A phrase that a Cunningham dancer improvised during the performance would most likely not enter the repertory; more important still, it would not have that quality of necessity Cunningham’s movements receive as a result of having been repeatedly rehearsed until mastered. It is not incidental to Cunningham’s aesthetic that spectators have frequently remarked on the “necessary”—rather than spontaneous—quality of the movement sequences, which I associate here with his handling of the arbitrary as an object to be preserved.5 The repetition of a phrase during the rehearsal period creates in performance an aura of necessity because the dancer knows precisely what she needs to do. But of course the performance situation, as a form of repetition, submits the learned phrase to contingency yet again.

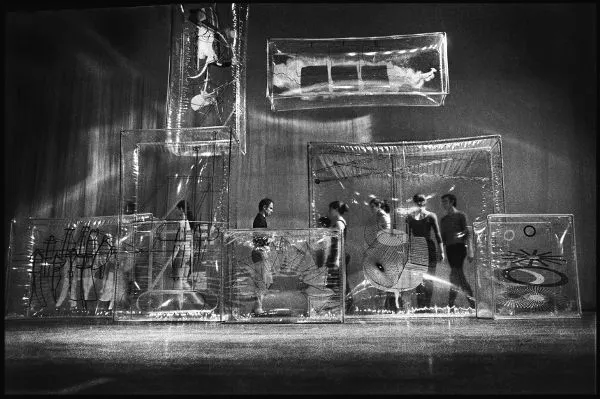

This chapter takes as its primary focus the paradoxical relation between the arbitrary and the necessary, the unexpected and its repetition, as it plays out in Cunningham’s Walkaround Time of 1968. (See figure 1.1.) Like Marcel Duchamp, he knew that contingency is solicited rather than suppressed by repetition because repetition always has a performative dimension. When Duchamp sought to counteract his own congealed habits (his training and “taste”6) by employing elements of chance, then congealing the aleatory results in “works” that he not only preserved but also multiplied—and thus altered—he inaugurated what is arguably the most productive line of questioning to animate the twentieth-century avant-garde, including the entire generation to which Cage and Cunningham belonged. As a performing artist, Cunningham was able to realize one of Duchamp’s cherished goals: to destabilize the category of the work through the category of the Event.7 Yet while some attention has been paid to the impact of Duchamp on Cunningham’s (and Cage’s) aleatory methods, few scholars have explored how Duchamp’s interest in the allied strategies of replication and recycling inform the performance genres that Cunningham developed.8

1.1

Merce Cunningham, Walkaround Time (1968). Photograph by James Klosty (1968). Reprinted with permission from James Klosty.

“Canning Chance”

According to his own testimony, Cunningham began using coin tossing as a compositional method in 1950–51 in order to short-circuit his own movement habits, which he believed would limit his power to invent. The procedure he used—often based on one that Cage had recently developed—involved generating dance sequences from a predetermined “gamut” of movements. He then preserved—recorded on paper—the results as a choreography so that they could be repeated over and over. The penultimate step (even after he became infirm in the 1980s) was to teach the sequence to the dancers, working with several or one at a time, depending on the effect he hoped to achieve.9

But the preserved phrase did not remain entirely unmodified, either during the step-by-step process of notation and acquisition or once the dancers had brought it to the stage. After generating, notating, and physically assimilating (through a brutal process of repetition) the chance-derived sequence—that is, after “canning chance,” to evoke Duchamp’s concise phrase—Cunningham added variables to the actual performance situation that would challenge the dancers’ ability to repeat with precision what they had learned—variables, in other words, meant to revive through repetition what was in the “can.”10 The noncollaborative collaborative process that Cunningham, Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg perfected in the 1960s expanded the scope of this performance practice, weaving together chance and archival preservation, the emergence of the new and the repetition of the habitual, the creation of the singular and the manufacture of the multiple. In repeatedly performing works that could not be replaced, Cunningham juxtaposed a set of “paradoxical principles,” revealing the insufficiency of a logic that opposes the work and the performance, anticipation and delay.11

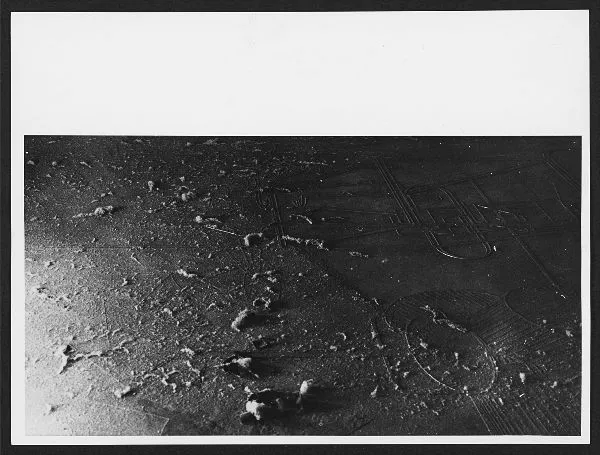

Duchamp first employed a method for conserving the products of a chance operation (or “canning chance”) in 1913 when he “composed” the score for his Erratum musical by drawing musical notes from a bag. For the second version of the piece, titled proleptically La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même: Erratum musical, he conceived of holding a funnel containing numbered balls—each number corresponding to a musical note—and letting the balls fall through the funnel into the open wagonettes of a toy train that ran at variable speeds.12 In both cases he transferred the sequence produced by chance onto a musical staff, thereby recording the results. He followed roughly the same procedure in Élévage de poussière of 1920, only with a photographic instead of a paper support. A shot by Man Ray captured for posterity the chance arrangement of dust particles as they had accumulated on the reverse side of Duchamp’s unfinished La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même of 1915–23 (otherwise known as Le grand verre, or The Large Glass). (See figures 1.2 and 1.3.) The practice of using photography to freeze or “can” a phenomenon that exists and evolves in time would become important to Cunningham as well.

1.2

Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Élévage de poussière (Dust Breeding) (1920). Photograph, gelatin silver print. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019. © 2019 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Marcel Duchamp Exhibition Records, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives.

1.3

Marcel Duchamp, La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, or The Large Glass) (1915–23). Oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 9 feet 1¼ inches × 70 inches × 3⅜ inches (277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952-98-1. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019.

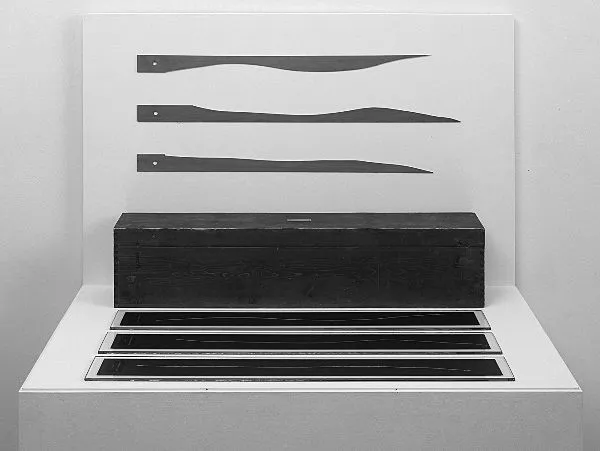

The evocative expression le hasard en conserve, “canned chance,” emerged from Duchamp’s pen in 1914 to describe a work he had been laboring on since 1913 titled 3 Stoppages étalon (3 Standard Stoppages).13 According to his account, to make 3 Standard Stoppages Duchamp dropped three lengths of string, each approximately a meter long, from the height of one meter from the floor. Using varnish, he then glued the dropped strings onto pieces of canvas and cut wooden shapes based on their curves, thereby preserving their aleatory plastic form for posterity. (See figure 1.4.) In The Green Box (1934)—a set of notes with which Cage and Cunningham were familiar—Duchamp underscored that his objective had been to allow each string to fall “as it pleases.”14 Thus, 3 Standard Stoppages perfected a procedure Duchamp would use many times—in Unhappy Readymade (1919),15 Élévage de poussière, and elsewhere—which consisted in preserving a “condition prevailing at a given moment” as a sculptural memento.16 Just as 3 Standard Stoppages froze the results of gravity first on canvas, then on wooden slats placed in a coffin-like box, so, too, works like Élévage de poussière turn accident into monument in a way that anticipates Cage’s and Cunningham’s chance-generated works. The procedures they developed during the 1950s—using I Ching hexagrams or imperfections on a sheet of paper to determine sequences (or continuities)—hark back to Duchamp’s early Dadaist gestures. In particular, the Duchampian archival logic of producing the aleatory, then freezing it or placing it inside a box (boîte) governs what we might call the archival logic of Cunningham’s choreographic practice.

1.4

Marcel Duchamp, 3 Stoppages étalon (Three Standard Stoppages) (1913; replica 1964). Mixed media, 400 × 1300 × 900 mm. Art © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019. Photo © Tate, London/Art Resource, NY.

Cage first met Duchamp in 1942 at the home of Peggy Guggenheim, but the entire Cage milieu—Cunningham as well as Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns—developed a closer acquaintance with him during the 1960s. Critics have long recognized that Duchamp’s influence on the postwar American neo-avant-garde was profound and long lasting. However, whereas Cage tended to emphasize Duchamp’s probing of authorial control through the invention of non-intentional methods, Johns became intrigued with Duchampian seriality. And while the generation of artists around Daniel Buren and Michael Asher focused on Duchamp’s institutional critique, Cunningham, as might be expected, took up Duchamp’s challenge to explore the relationship between movement and stasis, advancing and congealing, which the artist had investigated earlier in works such as Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (fig. 1.5). Cunningham’s homage to Duchamp, Walkaround Time of 1968, confirms that he was well aware of the legacy he was inheriting. From start to finish, this dance is a meditation on movement and immobility; it is also a rehearsal of Duchampian motifs: the nude, the machine (the simple motor), the transparency, and the “readymade.” Finally, Cunningham explored Duchamp’s procedures of reprisal and permutation, which rely on a modular approach to artisti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- (1) Recycling the Readymade: Marcel Duchamp and the Rendez-Vous in Walkaround Time

- (2) Summerspace: The Body in Writing

- (3) Nine Permanent Emotions and Sixteen Dances: Drama in Cunningham

- (4) “Passion in Slow Motion”: Suite for Five and the Photographic Impulse

- (5) Bound and Unbound: The Reconstruction of Crises

- (6) The Ethnics of Vaudeville, the Rhythms of Roaratorio

- (7) Buddhism in the Theatre

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Merce Cunningham by Carrie Noland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.