eBook - ePub

Landscapes of Accumulation

Real Estate and the Neoliberal Imagination in Contemporary India

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Landscapes of Accumulation

Real Estate and the Neoliberal Imagination in Contemporary India

About this book

Over the past few decades, India has experienced a sudden and spectacular urban transformation. Gleaming business complexes encroach on fields and villages. Giant condominium communities offer gated security, indoor gyms, and pristine pools. Spacious, air-conditioned malls have sprung up alongside open-air markets.

In Landscapes of Accumulation, Llerena Guiu Searle examines India's booming developments and offers a nuanced ethnographic treatment of late capitalism. India's land, she shows, is rapidly transforming from a site of agricultural and industrial production to an international financial resource. Drawing on intensive fieldwork with investors, developers, real estate agents, and others, Searle documents the new private sector partnerships and practices that are transforming India's built environment, as well as widely shared stories of growth and development that themselves create self-fulfilling prophecies of success. As a result, India's cities are becoming ever more inaccessible to the country's poor. Landscapes of Accumulation will be a welcome contribution to the international study of neoliberalism, finance, and urban development and will be of particular interest to those studying rapid—and perhaps unsustainable—development across the Global South.

In Landscapes of Accumulation, Llerena Guiu Searle examines India's booming developments and offers a nuanced ethnographic treatment of late capitalism. India's land, she shows, is rapidly transforming from a site of agricultural and industrial production to an international financial resource. Drawing on intensive fieldwork with investors, developers, real estate agents, and others, Searle documents the new private sector partnerships and practices that are transforming India's built environment, as well as widely shared stories of growth and development that themselves create self-fulfilling prophecies of success. As a result, India's cities are becoming ever more inaccessible to the country's poor. Landscapes of Accumulation will be a welcome contribution to the international study of neoliberalism, finance, and urban development and will be of particular interest to those studying rapid—and perhaps unsustainable—development across the Global South.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Landscapes of Accumulation by Llerena Guiu Searle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226385068, 9780226384900eBook ISBN

97802263852351

Routes of Accumulation

Gurgaon

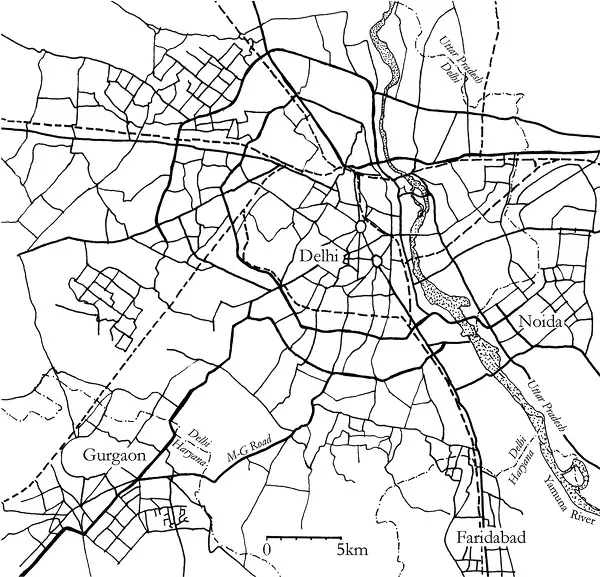

During my fieldwork, to get to Gurgaon, twenty kilometers southwest of central Delhi as the crow flies, you would travel south through the city’s variegated urban fabric and down the Mehrauli-Gurgaon Road (fig. 1.1).1 Its numerous lanes of traffic wind past wooded scrub, nurseries, and stone dealers; side lanes lead to villages and “farmhouses” (estates of the rich and famous). There is always at least one pani-wala with his umbrella-shaded metal box inscribed machine se thanda pani (machine-cooled water) serving the crowd at the bus stop at Andheria More, the major intersection where the traffic coming south along the Mehrauli-Gurgaon Road meets the traffic coming east from Vasant Kunj. You can also catch a ride from here in one of the SUVs that buzz up and down the road taking workers to Gurgaon’s call centers. On the right side of the road, behind a line of trees now marooned in traffic, people sell hand-forged metal implements from a row of huts. Andheria More gets its name from andheri, darkness, and mor, a turn. According to a friend who used to commute along this road, even a few years ago, there was “nothing” here; it was a turn into the darkness. Now this is a bustling thoroughfare, linking Delhi to up-and-coming Gurgaon.

Figure 1.1. Delhi and surrounding cities of the National Capital Region.

Source: Adapted from Eicher Delhi city map, Eicher Goodearth Limited, 2006. Drawn by author. Computer graphics by Joshua Enck.

Near the Delhi-Haryana line, the road turns to the right and rises, crossing the Delhi Ridge, as the tail end of the Aravalli hills is called. Here you can glimpse the occasional, lumbering nilgai (an Indian antelope) among the scrub and trees. From the ridge, you descend into a chaos of billboards selling alcohol and real estate: Gurgaon. The road zips past Corporate Park and the Global Business Park, each with large expanses of mirrored, tinted glass. The cream-colored walls of Garden Estate, one of the earliest gated housing complexes in Gurgaon, are visible behind walls of bougainvillea to the right. The road takes a tight bend at the village of Sikandarpur, past construction supply vendors and real estate brokers. Another sharp turn brings you to a strip of road where thirteen malls in different stages of construction elbow for space.

In front of the malls is a littoral zone of parking, pedestrians, and small shops with jaunty, jostling signs: plywood dealers, hardware vendors, painters, brokers, decorators, stone dealers, contractors, electricians. The city’s main business seems to be self-construction. Cars are parked higgledy-piggledy, overflowing designated parking areas. Shoppers wind past water-tanker tractors and chai stands to reach security-guarded, manicured mall entrance areas.

Gurgaon’s industrial clusters are along the National Highway-8: to the north, the Maruti automotive factory, started in the early 1980s, and to the south, Hero Honda scooters. Numerous multinational industrial suppliers have located near these plants. Since the late 1990s, alongside manufacturing, textiles, and pharmaceuticals, the information technology industry has boomed here. In 2006–7, Gurgaon accounted for 10 percent of the country’s software exports and its call centers employed between 150,000 and 200,000 people (GurgaonWorkersNews; Vinayak 2006). Familiar names like Nokia and Pepsi adorn Gurgaon’s Business Centers, World Trade Centers, and Info-Technology Parks.

To the north of the Mehrauli-Gurgaon Road, past the residential neighborhood DLF City Phase II (named after its developer, Delhi Land and Finance), DLF’s recent corporate venture, Cyber Greens, is actually blue with tinted glass and metal siding (fig. 1.2). To the south is DLF’s golf course, the American Express Building, and the concrete and rebar husks of the housing complexes coming up along Golf Course Road: the Palm Springs, the Exotica, the Pinnacle, the Belaire, La Lagune, and others. Cheap metal fencing lines Golf Course Road, supporting lush, colorful advertisements for as-yet-nonexistent places: happy families, romantic couples, swimming pools, and palms are all familiar motifs (fig. 1.3). Beyond the fencing and the sweeping entrance archways of future projects are muddy lots and dusty, windswept fields.

Figure 1.2. DLF Cyber Greens, Gurgaon, 2007.

Source: Photo by author.

Figure 1.3. Advertisements line Golf Course Road, Gurgaon, 2007.

Source: Photo by author.

Banners advertising “world-class” real estate and “international standard” construction crowd Gurgaon’s intersections. The new malls, housing complexes, and business parks being constructed in Gurgaon are not unique to India but familiar to cities the world over. New residential complexes offer amenities that might seem unremarkable to Americans: gyms, swimming pools, clubhouses, master bathrooms with his-and-hers sinks, open kitchens, and children’s rooms. However, such elements are new to Indian housing, as evidenced by the manuals for living that developers issue to new residents.

Gurgaon’s architecture is not merely self-consciously global; it is futuristic. Taking architectural cues from Dubai, Shanghai, Singapore, and California, Indian builders are imagining a global future and building it in Indian now. The buildings themselves—with their spiraling atriums, space-needle towers, and jutting prows—seem forerunners of a future age. Gurgaon’s futuristic malls, gated high-rise housing, golf courses, and five-star hotels tower over the remnants of fields and villages. Where once farmers grew mustard, employees of transnational corporations can now sip coffee or shop for Mercedes Benz cars. In popular media and everyday discourse, Gurgaon’s glitzy buildings have come to index India’s newfound prosperity and the country’s new footing on the global economic stage.

To understand how radical Gurgaon appears to many Indians, we must understand it in the context of Delhi’s existing landscapes. Gurgaon’s malls and high-rises contrast starkly with the narrow lanes of the walled seventeenth-century city built by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan; the grand avenues and monuments of Colonial New Delhi, built after the British moved their capital from Calcutta in 1912; the neighborhoods hastily allotted to some of the 500,000 refugees who flocked to the city after the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947; the spacious bungalows of South Delhi; and the neighborhoods built by the Delhi Development Authority in the state’s grand (but unsuccessful) bid to provide housing. Just as these landscapes tell us something about the time in which they were built, making Delhi’s architecture a palimpsest of its history, so too do Gurgaon’s malls and high-rises reflect the current era of liberalization.

Especially if we consider Gurgaon’s striking buildings as tools for making money, then understanding the city’s sudden growth requires understanding how developers—and now international fund managers—accumulate capital through the built environment. How did constructing Gurgaon come to seem profitable—and why in the 1990s and 2000s? I argue that the liberalization of the economy in the 1990s changed the structure of the real estate industry: it ushered in new roles for private-sector elites and spurred the growth of real estate–related markets such as mortgage financing and media, which precipitated the real estate boom that transformed Gurgaon into a sign of globalization.

Most importantly, accumulating capital through the built environment has entailed not just constructing buildings, but engaging with finance capital. Liberalization opened Indian real estate to new sources of finance capital from abroad, making foreign investors important new actors in the industry. In conjunction with Indian developers, consultants, lawyers, and bureaucrats, investors have attempted to transform Indian land and buildings from local resources for farmers or industrialists into international financial resources from which they can profit.

Liberalization

In India in 1970, state-run television only broadcast a couple of hours a day; a highly centralized and state-monitored film industry dominated music recording; foreign goods were hard to come by; only a few (Ambassador) cars plied the roads; and many construction companies worked exclusively for the government or for clients in the Middle East. Today, there is a proliferation of media—from satellite TV to regional-language newspapers—an influx of foreign goods and companies, and a construction boom.2

Many of these changes have roots in the1970s and 1980s, but the watershed moment to which scholars refer is 1991, when the Government of India repealed many of the protectionist policies of the Nehruvian state. With the aim of “making Indian industry globally competitive and increasing the extent of integration with the global economy” (Department of Economic Affairs 1996), the Government of India adopted reforms designed to tighten monetary policy; increase exports; reduce state involvement in industry, banking, and financial markets; and increase foreign investment.3 With these reforms, India opened its markets to networks of global finance and embarked on an “externally oriented, consumption-led path to national prosperity” (Mazzarella 2003, 5).

This external orientation has changed the game of real estate. The liberalization of the Indian economy precipitated a flurry of construction as developers scrambled to construct space for foreign tenants, non-resident Indians, and an Indian nouveau riche. As they used new sources of finance to do so, they have helped develop Indian real estate as a financial instrument in its own right, a means for foreign firms and wealthy Indians to invest in Indian buildings alongside stocks and bonds. I turn now to the legal and institutional changes that have enabled Indian real estate to grow so rapidly.

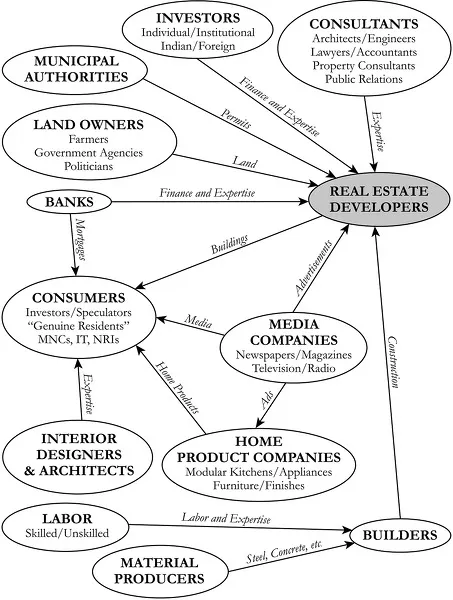

Interconnected Markets and the Real Estate Developer’s Role

To understand the effects of liberalization on the Indian real estate market, it helps to visualize “Indian real estate” as a series of interconnected markets for building-related products and services. These include markets in land, permits, construction materials, project finance, consulting services, mortgages, media about real estate, consumer durables, and home decorating products (fig. 1.4). Each of these interrelated markets consists of buyers and sellers, of course, but many of the buyers are real estate–related companies (construction, media, and consulting firms, for example) rather than building occupiers (home buyers or corporate tenants). Each of these interconnected markets has grown over the last twenty years, especially since liberalization.4

Figure 1.4. The Indian real estate industry consists of numero...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Money Terms

- Introduction: Building Stories

- 1 Routes of Accumulation

- PART I Speculating on Indian Futures

- PART II Conflict and Commensuration

- Notes

- References

- Index