eBook - ePub

All the World's a Fair

Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

All the World's a Fair

Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916

About this book

A groundbreaking account of the ways the United States used world's fairs to extend its empire abroad and racial hierarchies at home

In All the World's a Fair, Robert W. Rydell argues that America's nineteenth-century world's fairs served to legitimate racial exploitation at home and the creation of an empire abroad. He looks in particular to the "ethnological" displays of nonwhites—set up by showmen but endorsed by prominent anthropologists—which lent scientific credibility to popular racial attitudes and helped build public support for domestic and foreign policies. Rydell's lively and thought-provoking study draws on archival records, newspaper and magazine articles, guidebooks, popular novels, and oral histories to tell a new story of American history and empire.

In All the World's a Fair, Robert W. Rydell argues that America's nineteenth-century world's fairs served to legitimate racial exploitation at home and the creation of an empire abroad. He looks in particular to the "ethnological" displays of nonwhites—set up by showmen but endorsed by prominent anthropologists—which lent scientific credibility to popular racial attitudes and helped build public support for domestic and foreign policies. Rydell's lively and thought-provoking study draws on archival records, newspaper and magazine articles, guidebooks, popular novels, and oral histories to tell a new story of American history and empire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access All the World's a Fair by Robert W. Rydell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780226732404, 9780226732398eBook ISBN

97802269232531

The Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876: The Exposition as a “Moral Influence”

Come back across the bridge of time

And swear an oath that holds you fast,

To make the future as sublime

As is the memory of the past!

Fourth of July Memorial, 1876

He was a young man, evidently just fresh from some interior village. He was naturally no fool, but it could be plainly seen that he knew next to nothing of men or of the world, and that his visit to the world’s fair was the crowning event in his quiet life.

New York Times, 1876

The teachings survive the demolition of the buildings.

William P. Blake, 18721

ON THE OVERCAST MORNING of 10 May 1876, the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia officially opened to the public. The 186,672 visitors to the fairgrounds that first day began a stream of almost ten million people who saw the exhibition. Before its conclusion in mid-November, nearly one-fifth of the population of the United States passed through the turnstiles, making the attendance at this international exposition larger than at any held previously in any country.2

After early apathy, ambivalence, and even outright hostility to the enterprise, a sense of growing anticipation began building in the City of Brotherly Love in early 1876 and spread throughout the country. It had become, in the words of one newspaper, a “swelling act.” Foreign and domestic newspaper correspondents found ample copy as exhibit halls filled with displays ranging from exquisite, exotic silks to practical tools and to “Old Abe,” the Wisconsin war eagle that had been in thirty-six Civil War battles.3

Life in Philadelphia was a story. With the price of lodging in the lead, the cost of living soared. “Prices have gone up fifty per cent, with indications that the maximum of extortion has not been reached by any means,” declared the New York Times. One firm went so far as to purchase Oak Cemetery, remove the tombstones, and erect a campground to handle the expected overflow crowds from boardinghouses. “Philadelphia,” Harper’s Bazaar had quipped in March, “appears for the nonce to have thrown off her sombre Quaker apparel, and to have ushered in the Centennial with much the air of a venerable old lady endeavoring to execute some difficult steps in the can-can.” This description, while good-natured, was both revealing and misleading. The international exposition, like the cancan, was a novelty of comparatively recent origin, the first international exposition having taken place in London in 1851. Yet the men and women who organized the Centennial Exhibition were not wholly inexperienced with the medium of fairs. Several of the directors had participated in the Sanitary Fairs held in Philadelphia during the Civil War. And the war itself had taught many army officers, who later became exposition officials, lessons in efficient management and organization. Furthermore, Alfred T. Goshorn, director-general of the Centennial Commission, far from being a newcomer to fairs, had been in charge of industrial exhibitions in Cincinnati since the conclusion of the war. And, if Harper’s metaphor of the cancan was not entirely apt, neither was its stereotypical conception of Philadelphia’s earlier dourness. Philadelphia’s Quaker roots had nothing to do with the gloom that had settled over the city and the whole country. The unhealed social and political wounds left by the war would have been difficult to cope with in the best of circumstances, but these problems had been compounded manyfold by the industrial depression of 1873. By 1876 the Gilded Age had already earned its name. But if Philadelphians could find an almost comic relief from the unsettled condition of the country in the spectacle of a world’s fair, perhaps other Americans, as Harper’s recommended, could do likewise. Minimally, the exposition promised a diversion from endless accounts of political corruption in Washington, collapse of financial and mercantile establishments, and stories of working-class discontent with the industrial system.4

From such gloomy vistas, the Centennial Exhibition provided a welcome change. Yet, rather than merely offering an escape from the economic and political uncertainties of the Reconstruction years, the fair was a calculated response to these conditions. Its organizers sought to challenge doubts and restore confidence in the vitality of America’s system of government as well as in the social and economic structure of the country. From the moment the gates swung open at nine o’clock on the morning of 10 May, the fair operated as “a school for the nation,” a working model of an “American Mecca.”5

Despite the rain, which the day before had drenched the city and turned portions of the fairgrounds into a quagmire of mud and rotting straw, crowds began arriving several hours before the ceremonies were scheduled to get under way. The fair, occupying a portion of Fairmount Park’s three thousand acres, was situated on a plateau intersected by wooded dells and meandering streams. From the high points of the elevation visitors could gaze upon the Schuylkill River, the exhibition buildings, and the central city.6

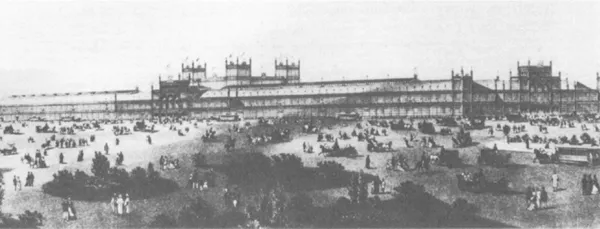

The major buildings themselves were colossal edifices. Along the southern edge of the grounds was the Main Building, 1,880 feet long by 464 feet wide. The wood, iron, and glass structure was the largest in the world. West of the Main Building, and next largest, was Machinery Hall. On the northern portion of the fairgrounds was another gigantic structure, Agricultural Hall. Devoted to displays of agricultural machinery, its modified Gothic outlines covered more than ten acres. On a line between Agricultural Hall and the Main Building was Horticultural Hall, the most ornamental of the exposition buildings. The interior contained specimens of exotic plants, model greenhouses, gardening tools, and elegant containers. Twenty feet above the floor a gallery encircling the building afforded a view “as entrancing as a poet’s dream.” Taken in its totality, the interior scene added up to “an Arabian Nights’ sort of gorgeousness.” Between Horticultural Hall and the Main Building was Memorial Hall, “the most imposing and substantial of all the Exhibition structures,” which housed paintings and sculpture from around the world, including “Iolanthe,” an extraordinary “alto-relievo . . . in butter,” sculpted by an Arkansas woman.7

In addition to the five main exhibition buildings, there were seventeen state buildings, nine foreign government buildings, many restaurants, six cigar pavilions, popcorn stands, beer gardens, the Singer Sewing Machine Building, the Photograph Gallery, the Turkish Coffee Building, the Shoe and Leather Building, the Bible Pavilion, the Centennial National Bank, the New England Log House, a Nevada Quartz Mill, a Woman’s School House, and, significantly, the Woman’s Pavilion. The exhibition directors had even granted permission for a Burial Casket Building—much to the embarrassment of Americans concerned with proving the cultural worth of their country to European visitors.8

Fig. 1. Centennial vision of American progress. Cover, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Monthly, 1, no. 3 (1876), courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Library, California State University, Fresno.

The throngs rushing through the 106 entrances, each adorned with “American trophies, shields, flags, eagles, etc.,” could well anticipate all of this and a great deal more with the help of newspaper coverage and guidebooks to the exposition. But seeing was believing. Statues and fountains added to the splendor. West of Machinery Hall was the immense, but incomplete, Centennial Fountain, designed by Herman Kim and funded by the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America. The central figure was an enormous statue of Moses atop a granite mass in the midst of a circular basin forty feet in diameter. Around the basin, drinking fountains were set at the bases of nine-foot marble statues representing prominent American Catholics. Other monumental figures abounded. B’nai B’rith erected a statue of Religious Liberty, twenty feet tall, that had as its centerpiece a female warrior with the American shield for a breastplate, typifying “the genius of liberty.” Near the base of the figure was an eagle clutching a snake in its talons, representing the end of slavery. Completing the allegory were inscriptions from the Constitution. Other heroic statues dotted the exhibition grounds. In addition to representations of Columbus and Elias Howe, there was the American Soldier’s Monument, weighing thirty tons, and the John Witherspoon Memorial erected by American Presbyterians. French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi sent over the Torch of Liberty from the as yet unfinished Statue of Liberty. And, as a monument to the Victorian age of which the Centennial Exhibition was a part, there was also a statue of Thomas Carlyle. This setting, at once pastoral and heroic, appealed to many fairgoers. “Dear Mother,” wrote a young woman after seeing the grounds, “Oh! Oh!! O-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o!!!!!!”9

Unlike many subsequent fairs, the landscaping was largely completed and almost all the buildings and exhibits were ready by opening day. The crowds rapidly filled every available space across from the platforms erected for the ceremonies between the Art Building and the Main Building. Some climbed statues, and others found their way to rooftops. “A hundred thousand people in a crowd and not one peasant,” commented a journalist. A local correspondent found in the crowd a hierarchy “suggestive of a modernized Babel without its guilt and folly, in the confusion of the various forms of human language to be heard, from our own familiar and vigorous Anglo-Saxon to the guttural of our barbaric Aboriginese, or the sing-sing jargon of the ‘heathen Chinese.’” Newspapers tried to foster the impression that people from foreign countries were “treated with the utmost respect and courtesy” and that the crowd, above all, was orderly even in the absense of direct military supervision. Generally overlooked were expressions of racial hostility that followed the decorous opening proceedings. Turks, Egyptians, Spaniards, Japanese, and the Chinese, a contemporary noted, “were followed by large crowds of idle boys and men, who hooted and shouted at them as if they had been animals of a strange species instead of visitors who were entitled to only the most courteous attention.” This outburst of racial hostility did not detract entirely from the general orderliness of the crowd during the ceremonies and the exposition as a whole. Rather, it revealed that white Americans brought their accumulated racial attitudes with them to the fair and that fairgoers found nothing in the opening ceremonies to negate their racial assumptions.10

Fig. 2. Main Building, Centennial Exhibition. Lithograph courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Photograph Collection.

In describing the opening ceremony, Reverend D. Otis Kellogg explained the orderly nature of the crowds as being a direct result of the impression created by “the majesty of the exposition itself.” “The imposing edifices were there to speak,” he observed, “and emphatically do they do their work. With an effect like some of the European Cathedrals, the Main Building exceeds any of them in extent many times over. . . . Then there were the eminent men of the land coming as representatives of the power of the country to acknowledge the grandeur of Industry.” It was precisely the religious aura about the opening that led the Philadelphia Press to declare: “Let us, therefore, to-day bare our heads and take off our sandals, for we tread on holy ground.” This effort to shape American culture, however, would have been incomplete without the explicitly didactic lessons provided by the speakers themselves.11

Introduced with music composed by Richard Wagner and conducted by Theodore Thomas, the ceremonies emphasized national unity and America’s destiny as God’s chosen nation. Hope for the future provided the text for the speech delivered by Joseph R. Hawley, president of the Centennial Commission. He expressed his “fervent hope” that “all parties and classes” would come to the exhibition “to study the evidence of our resources, to measure the progress of a hundred years, and to examine to our profit the wonderful products of other lands.” President Grant concluded the speechmaking by urging the audience to make “a careful examination of what is about to be exhibited to you,” bearing in mind that America’s greatest achievements still lay in the future.12

Fig. 3. Machinery Hall seen through the Finance Building. Stereoscope card from Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

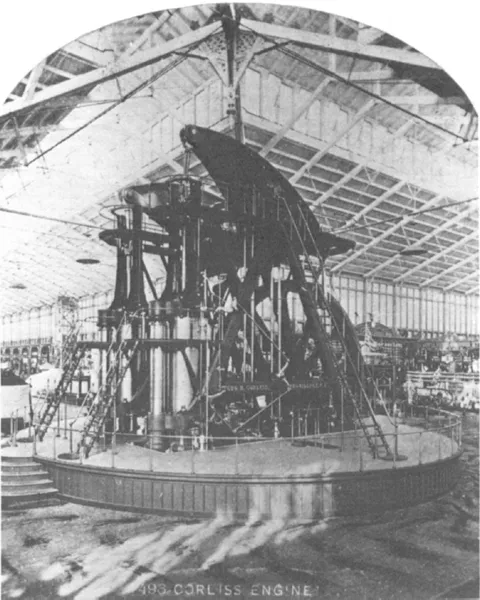

When the orchestra and chorus played the “Hallelujah Chorus” at the conclusion of Grant’s remarks, one phase of the inaugural proceedings was complete. The climax, however, had yet to occur. President Grant, Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil, and Director-General Goshorn took their places at the head of a procession of four thousand invited dignitaries. After reviewing the foreign and domestic displays in the Main Building, they arrived at the exposition’s centerpiece, the Corliss engine, in Machinery Hall. George Corliss, commissioner from Rhode Island and designer of the machine, gave operating instructions to the two heads of state. Then both men turned wheels and started the generator that provided the power for the exhibits in Machinery Hall.13

The Corliss engine was the most impressive display on the exhibition grounds. With its steam boiler tucked out of sight and earshot in an adjacent power supply building, the engine, despite its size, ran with an awesome, silent power—“an athlete of steel and iron.” When Walt Whitman visited Machinery Hall several weeks later, “he ordered his chair to be stopped before the great, great engine . . . and there he sat looking at this colossal and mighty piece of machinery for half an hour in silence . . . contemplating the ponderous motions of the greatest machinery man has built.” His less renowned companion, California poet Joaquin Miller, summed up the reaction of many not only to the Corliss engine, but to the fair as a whole: “How the American’s heart thrills with pride and love of his land as he contemplates the vast exhibition of art and prowess here.” “Great as it seems today,” Miller forecast, “it is but the acorn from which shall grow the wide-spreading oak of a century’s growth.”14

Fig. 4. Corliss engine: “An athlete of steel and iron.” From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Any number of exhibits—the Westinghouse air brake, various refrigeration processes, the telephone, Vienna bread, Fleischmann’s yeast—could be singled out as ample proof of Miller’s prediction that the fair would have a lasting impact on American life. Just as profound as any single exhibit or group of displays, however, were the values and ideas that channeled the exhibits into a coherent picture. As the opening-day speeches made clear, the exposition was intended to teach a lesson about progress. The lesson was far from benign, for the artifacts and people embodied in the “world’s epitome” at the fair were presented in hierarchical fashion and in the context of America’s material growth and development. This design well suited the small group of affluent citizens who organized the Centennial into a dynamic vision of past, present, and future.15

Several persons originated the idea of celebrating America’s centennial with an international exhibition. The most influential was probably John L. Campbell, a professor at Wabash College in Indiana, who proposed a commemorative fair in an 1864 address delivered at the Smithsonian Institution. In the heat of the war the response to his proposal was lukewarm. Selective prodding of congressmen and public officials in Philadelphia by Campbell, John Bigelow, Charles B. Norton, and M. Richards Mucklé, however, finally led the Select Council of Philadelphia, on 20 January 1870, to endorse unanimously the plan for an international exhibition. The council was next joined by the Franklin Institute and the state legislature, which presented memorials to Congress urging federal sanction for the event. Daniel J. Morrell, representative from Pennsylvania, chairman of the House Committee on Manufactures, and “one of the most eminent and successful [iron] manufacturers of Pennsylvania,” guided the bill through Congress. In its final form the bill empowered the president to appoint commissioners from the states and territories upon the recommendation of the governors. At its first meeting in March 1872, Joseph R. Hawley was elected president of the United States Centennial Commission and Campbell, by this time a commissioner from Indiana, was elected secretary. Hawley, formerly a Civil War major general, had served as governor and congressman from Connecticut and become a successful Hartford newspaper publisher. His administrative skill was widely recognized, but the Centennial promised to be an immense project. So, soon after the first meeting of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876: The Exposition as a “Moral Influence”

- 2. The Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893: “And Was Jerusalem Builded Here?”

- 3. The New Orleans, Atlanta, and Nashville Expositions: New Markets, “New Negroes,” and a New South

- 4. The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, Omaha, 1898: “Concomitant to Empire”

- 5. The Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo: “Pax 1901”

- 6. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, Saint Louis, 1904: “The Coronation of Civilization”

- 7. The Expositions in Portland and Seattle: “To Celebrate the Past and to Exploit the Future”

- 8. The Expositions in San Francisco and San Diego: Toward the World of Tomorrow

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index