eBook - ePub

Race and Photography

Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876-1980

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Race and Photography studies the changing function of photography from the 1870s to the 1940s within the field of the "science of race," what many today consider the paradigm of pseudo-science. Amos Morris-Reich looks at the ways photography enabled not just new forms of documentation but new forms of perception. Foregoing the political lens through which we usually look back at race science, he holds it up instead within the light of the history of science, using it to explore how science is defined; how evidence is produced, used, and interpreted; and how science shapes the imagination and vice versa.

Exploring the development of racial photography wherever it took place, including countries like France and England, Morris-Reich pays special attention to the German and Jewish contexts of scientific racism. Through careful reconstruction of individual cases, conceptual genealogies, and patterns of practice, he compares the intended roles of photography with its actual use in scientific argumentation. He examines the diverse ways it was used to establish racial ideologies—as illustrations of types, statistical data, or as self-evident record of racial signs. Altogether, Morris-Reich visits this troubling history to outline important truths about the roles of visual argumentation, imagination, perception, aesthetics, epistemology, and ideology within scientific study.

Exploring the development of racial photography wherever it took place, including countries like France and England, Morris-Reich pays special attention to the German and Jewish contexts of scientific racism. Through careful reconstruction of individual cases, conceptual genealogies, and patterns of practice, he compares the intended roles of photography with its actual use in scientific argumentation. He examines the diverse ways it was used to establish racial ideologies—as illustrations of types, statistical data, or as self-evident record of racial signs. Altogether, Morris-Reich visits this troubling history to outline important truths about the roles of visual argumentation, imagination, perception, aesthetics, epistemology, and ideology within scientific study.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Race and Photography by Amos Morris-Reich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226320885, 9780226320748eBook ISBN

9780226320915Chapter 1

The Type and the Gaze: Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876–1918

Three genealogical threads converge in scientific racial photography of the 1920s and 1930s within the context of German society. These threads are intimately connected to transformations in the conceptualization of race from Carl Victor and Friedrich Wilhelm Dammann’s Races of Men of 1876 to Hans F. K. Günther’s Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes of 1922.

In the first section of this chapter, I commence with a short note on Dammann’s Atlas and then reconstruct three indispensable moments in the history of anthropometric photography: Alphonse Bertillon’s anthropometric photography, Francis Galton’s composite photography, and Rudolf Martin’s standardization of anthropometric photography. A particular emphasis will be placed on questions of scientific control and transformations in the epistemological status of photography. Within this genealogy, photography is intimately connected to statistics, a connection that finds expression in the emergence of a specific visual code as well.

In the second part of the chapter, I shift the perspective to a parallel and lesser-known genealogy that was intricately tied to the emergence of Mendelian genetics. This genealogy, developed by Carl Heinrich Stratz, Redcliffe N. Salaman, and Eugen Fischer, could be termed Mendelian photography. Focused on the study of the gaze as a specific racial characteristic, this genealogy increasingly involved the question of the visible versus the invisible in the photograph. I argue that it is crucial for understanding racial writers of the Weimar and Nazi period.

In the final part of the chapter I turn to yet a different intellectual discourse. I examine the antimechanistic notions of “seeing” elaborated in German philosophy and history of art through the discussion of two books, one by sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel and the other by historian of art Heinrich Wölfflin.

If anthropometric genealogy lent prestige to the use of photography as a major scientific device in the study of race, the photographic study of the gaze was appropriated and further developed by Weimar and Nazi writers toward racial observation. While photography was tied to anthropological notions of race, the idea that seeing was relative to race was not simply a pseudoscientific argument concerning neurological differences between races. Rather, this concept was based on ideas that were drawn from cultural relativism and in fact constituted a reinterpretation of ideas expressed by major intellectual figures such as Simmel and Wölfflin.

Part One: Anthropometric Photography

Alphonse Bertillon, Francis Galton, and Rudolf Martin could be described as the three most important figures in the history of anthropometric photography from 1880 to 1920.1 Each was instrumental in establishing the use of photography as a measuring device in the study of race as well as the scientific prestige it came to enjoy within science and wider culture.

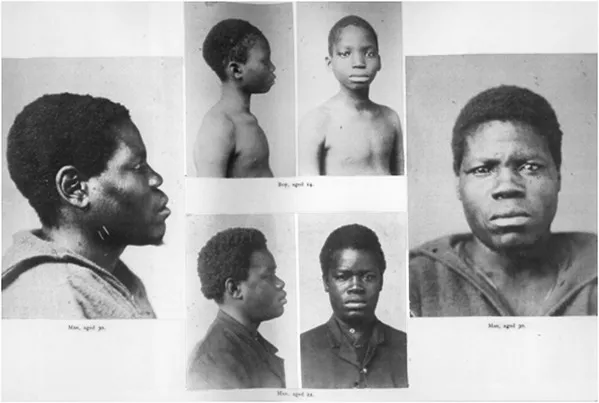

Photography was integrated into anthropological work from its very inception in the middle of the nineteenth century.2 Carl Victor and Friedrich Wilhelm Dammann’s famous Races of Men, arguably the most influential racial photographic book of the nineteenth century, can serve as a starting point in examining the transformations in the role of photography for the study of race and their shifting epistemological underpinnings between the 1880s and 1918. The “brothers Dammann’s book” (in fact they were not brothers), which appeared in England in 1876, is conceived as a photographic atlas of the different races of man. In this album-sized book, each page comprises high-quality black-and-white photographic reproductions, which appear accompanied by titles and coupled with brief textual descriptions of central physical and mental traits of the respective type that appear in small print under the photographs. As customary in contemporary botanical atlases, individual humans were presented as specimens of their type and are seen to correspond with the central traits of the type. The atlas as a whole, conceived along an evolutionary scale, moves from what they perceived as primitive types to the highly developed ones: from the Polynesian to the Germanic.3 Photographs merely illustrate for the general readership the gallery of types that make up the human species (fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1. “Zanzibar Coast.” Dammann’s Ethnological Photographic Gallery consists of racial type photographs. Pages are composed of large photographs accompanied by short textual description of typical features (“the skull of the Negro is remarkably solid and thick, so that in fighting they often butt against each other like rams, without much damage to either combatant”). Carl Victor and Friedrich Wilhelm Dammann, Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men (London: Trübner, 1876), plate 16.

But before I turn to their cases in more detail, I cannot avoid a short note on antisemitism in this respect. Both Bertillon and Galton were involved in antisemitic campaigns and expressed antisemitic views: as an expert on identification, Bertillon took an active part in the Dreyfus affair.4 Galton, after completing a composite photograph of Jewish schoolboys, wrote on one occasion that he was struck by the diffidence of the Jewish gaze.5 Antisemitism, therefore, while not central to their discussions of photography, was culturally and ideologically associated with this scientific genealogy.

Alphonse Bertillon: Measurement and Identification

Alphonse Bertillon was not an anthropologist or an academic, but as the founder of modern anthropometric photography, his contributions to the field are essential for a historical account of the development of anthropometric photography from the final decades of the nineteenth century through the first decades of the twentieth. Bertillon developed the anthropometric method toward different goals than Galton or Martin, emphasizing the significance of practical considerations in the development of scientific photography.

Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914) was the son of Louis Adolphe Bertillon, a physician and statistician. After being expelled from the Imperial Lycée of Versailles, Bertillon held a number of jobs in England and France before being conscripted into the French army in 1875. In 1879, after his discharge, with no real higher education, his father arranged for his employment in a low-level clerical job at the prefecture of police in Paris. Bertillon, whose duty included copying onto small cards the descriptions of criminals apprehended each day, realized that what he was laboriously rerecording was practically useless for the purpose of identifying recidivists. With a general familiarity with anthropological statistics and anthropometric techniques from his father and brother, he devised a system of identification that relied on eleven different bodily measurements and the color of the eyes, hair, and skin. This system proved so successful in identifying recidivists that it was quickly adopted by all developed countries, and Bertillon himself became the head of the Department of Judicial Identity, created for the Paris prefecture of police in 1888.6

Toward the method of identification, Bertillon introduced photographic methods that revolutionized existing ones. Like Rudolf Martin later, as we will see, Bertillon was less interested in photography as a medium than in its service for criminological practices. He recognized that the main problems in identification of criminals lay not in making good photographic likenesses but in being able to classify or compare them. He was the first to develop, in 1883, a photographic archive: a card-based system that allowed easy retrieval of stored data based on strict uniformity. The card listed a range of physical characteristics, and from 1892 onward, fingerprints, to supplement exact one-seventh-scale photographs. He described his system in Photography: With an Appendix on Anthropometrical Classification and Identification (1890).

Bertillon’s aims were practical and operational, the identification of individuals—a response to the demands of urban police work and the politics of fragmented class struggle during the Third Republic. While working toward different goals, the uses of photography by Bertillon, Galton, and Martin were in different ways grounded in the emergence and codification of social statistics in the 1830s and 1840s and relied heavily on the notion of the l’homme moyen. This term was coined by astronomer and statistician Adolphe Quetelet, who showed statistical regularities in rates of birth, death, and crime.7 Galton and Martin both connected this notion to that of a “central type,” while in contrast, Bertillon did not address this issue, as his aim was practical: individual identification. Of particular importance for the use of photography by 1920s and 1930s racial writers was scientific control, the relationship between visibility and invisibility, and the relationship between photography and statistics.

Strict control was essential to Bertillon’s anthropometric system. One of the major problems with earlier attempts at criminal identification concerned standardization of portraits. The precise method Bertillon invented to register offenders and classify the photographs to guarantee their retrieval is less important in our context than the fact, in the words of Allan Sekula, that Bertillon was engaged in a “two-sided taming of the contingency of the photograph.”8 In order to compare two photographs and to carry out and compare measurements with archived photographs, Bertillon realized, control was absolutely necessary. Control, however, was not unique to photography but rather to measurement as such. Bertillon insisted on a standard focal length, even and consistent lighting, and a fixed distance between the camera and the sitter. He introduced the profile view to cancel the contingency of expression, as the contour of the head remained consistent with time.9

In a recent doctoral dissertation, Josh Ellenbogen has argued that Bertillon’s use of photography established an approach to identity that was “stripped of the idea of resemblance.”10 Bertillon’s photographic method did not aim at images that would resemble the photographed but in fact were based on a certain form of alienation, on training the eye to know how to interpret. Bertillon systematically differentiated between the professionally educated eye and the layman’s.11 Bertillon’s method was designed for the professionally trained eye, which “means nothing in relation to the world of quotidian appearance, is worthless to the inexpert eye.”12 As opposed to the racial writers of the 1920s and 1930s, however, Bertillon sought to establish the kind of “seeing” that he conceived as nonintuitive or innate but conventional and learned (fig. 1.2).13

For the untrained policemen, for friends or family of the prisoner, the frontal view of a face was more likely to be recognizable.14 From the profile photograph anyone, including the prisoner himself, will have great difficulty at identification. The trained eye was dependent on particular conventions and their minute execution precisely because they were not based on memory ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Note about Scanning and Reproduction of Photographs

- Introduction

- 1 · The Type and the Gaze: Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876–1918

- 2 · Racial Photographs from Icons to Schemes: The “Case” of Central and Eastern European Jews, 1880–1927

- 3 · Serialization as Construction of Meaning: The Photographic Practice of Hans F. K. Günther in Context

- 4 · Racial Photographs as “Thought Experiments”: The Photographic Method of Ludwig Ferdinand Clauß

- 5 · Racial Photography in Palestine

- Notes

- Index