eBook - ePub

The Remittance Landscape

Spaces of Migration in Rural Mexico and Urban USA

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Immigrants in the United States send more than $20 billion every year back to Mexico—one of the largest flows of such remittances in the world. With The Remittance Landscape, Sarah Lynn Lopez offers the first extended look at what is done with that money, and in particular how the building boom that it has generated has changed Mexican towns and villages.

Lopez not only identifies a clear correspondence between the flow of remittances and the recent building boom in rural Mexico but also proposes that this construction boom itself motivates migration and changes social and cultural life for migrants and their families. At the same time, migrants are changing the landscapes of cities in the United States: for example, Chicago and Los Angeles are home to buildings explicitly created as headquarters for Mexican workers from several Mexican states such as Jalisco, Michoacán, and Zacatecas. Through careful ethnographic and architectural analysis, and fieldwork on both sides of the border, Lopez brings migrant hometowns to life and positions them within the larger debates about immigration.

Lopez not only identifies a clear correspondence between the flow of remittances and the recent building boom in rural Mexico but also proposes that this construction boom itself motivates migration and changes social and cultural life for migrants and their families. At the same time, migrants are changing the landscapes of cities in the United States: for example, Chicago and Los Angeles are home to buildings explicitly created as headquarters for Mexican workers from several Mexican states such as Jalisco, Michoacán, and Zacatecas. Through careful ethnographic and architectural analysis, and fieldwork on both sides of the border, Lopez brings migrant hometowns to life and positions them within the larger debates about immigration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Remittance Landscape by Sarah Lynn Lopez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9780226202815, 9780226105130eBook ISBN

97802262029521 The Remittance House

Dream Homes at a Distance

In the small town of Pegueros, in the region of Los Altos, Jalisco, Antonio Rodríguez built three new houses, each one an improvment on the last. The first incorporated several sculptural and ornamental features, including an inscription on the entryway lintel, beneath a miniature cupola. It reads (in English), “DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS.” On this house situated across the street from his childhood home, the inscription addresses his parents each day when they leave their house to buy food or spend time in the plaza. While they will not see Antonio, who lives and works in Los Angeles, his homage remains. All three houses remain vacant or occupied by a villager who guards and maintains the property. Daily, these arrangements, and the houses themselves, demonstrate Antonio’s gratitude to family and the pueblo in his absence.

Located on a rather drab street between two unadorned peso houses, this sculptural home is an exceptional example of what I call the remittance house. I use this term to refer to a house built with dollars earned by a Mexican migrant in the United States and sent—remitted—to Mexico for the construction of his or her dream house. More broadly, I use this term to emphasize remitting and migration as key components of contemporary long-distance building practices around the globe.1 While such houses exhibit similarities, every remittance house is unique and embodies the specific circumstances of the migrant who finances and builds it. Some migrants and their families build informally, adding rooms as the need arises, while others use architectural plans to construct entirely new houses on their land. Understated facades may blend in with the surrounding buildings, or highly ornamental designs may announce a migrant’s success abroad. In Mexico, dating back to at least the middle of the twentieth century, the remittance house has crystallized migrant narratives and desires amid shifting cultural milieus. As artifacts of complex relationships, these houses are also embedded in the macro processes of globalization and transnational migration.

Figure 1.01. Ornamental, hand-carved cantera stone (soft limestone quarried locally) frames the entry of Antonio Rodríguez’s remittance house in Pegueros, Jalisco. An inscription above the doorway reads, “DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS.” Photograph by author.

For at least a century, American immigrants’ remittances have dramatically affected the vernacular rural landscapes of their hometowns. As early as 1913, the New York Times observed that Italian immigrant laborers “go back when they have accumulated American money, buy property and restore it,” with the result that “in squalid villages stand new, clean houses” built by “Italians who have come back from America.”2 Similarly, the Chinese built remittance houses in the late nineteenth century for family members who remained in China. Today, Turkish migrants in Germany, Portuguese migrants in France, and Central American migrants in the United States use hard-earned wages to build new houses in their hometowns.3

The current scale of remitting and the continuous movement of migrants between Mexico and the United States are unprecedented. This fast-growing sector of the economy is spearheading home building for migrants and their families throughout Mexico.4 However, the consequences of imagining, building, and living in these homes for local communities, family life, and local construction practices and markets have received scant attention.5

This chapter explores how the forms of remittance houses not only embed social meanings but also structure social life and relations between individuals, genders, classes, and groups and establish categories or descriptions fundamental to society.6 Houses—a critical space of migration—reflect and reproduce the social condition of migrants. I examine the meanings and implications of remittance houses through geographically and historically contextualized ethnographies of migrants and their families. Because remittance projects are often informal—paid for in cash without contracts or documentation—I rely on narrative accounts of migrants and migrant families as a primary source for understanding how they spend remittances, the motives that drive them, and the unique history of individual building projects. Architectural analysis of these houses defines the remittance house as a unit of analysis for larger social, political, and architectural discourses about migration and global building practices in rural places. Remittance houses are emblems of the rising social status of once impoverished rural farmers. Yet the houses and the specific forms they take also have unintended consequences that many migrants did not anticipate when building them. For example, the increased symbolic value of the house frequently corresponds to a diminished functional or use value, as migrants living in the United States are unable to occupy them. Similarly, architectural styles and spaces suggest lifestyles that remain unattainable for most. The remittance house can be read both architecturally and allegorically—it is both a house form and a crystallization of the inequities that underpin migrants’ lives.

The spaces of the remittance house are also indicators of a profound transformation in rural Mexican society.7 Perhaps the single most striking quality of remittance construction is the social distance embedded in its form. Scholars of the built environment can contribute to the study of how migration is transforming rural Mexican society by analyzing changes in spatial form at both migrants’ places of origin and their point of arrival.8 Social relations stretched across geographies and exacerbated by distance increasingly define local places. The price of improving the domestic dwelling is abandoning it, and investments in the community can end up producing new social and spatial divisions within it. Absence is a necessary precondition for migrants to realize their dream house.

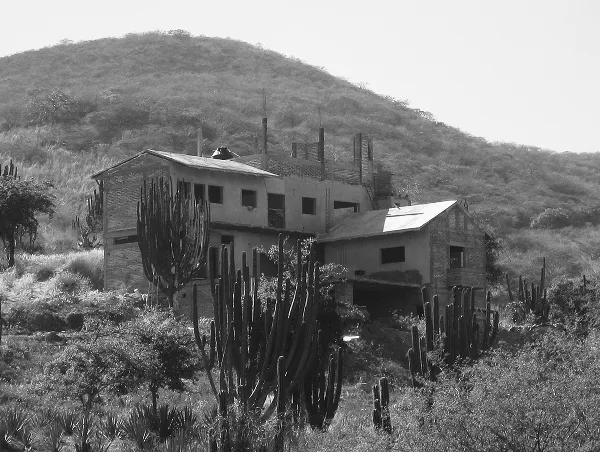

Figure 1.02. Unfinished remittance house, San Miguel Hidalgo, Jalisco. Photograph by author.

The Village in Historical Context

Jalisco, Mexico, is located about fifteen hundred miles south of the US-Mexico border along the Pacific Coast. It is one of the Mexican states with the highest rates of emigration.9 Migration to the United States from rural Jalisco dates back to the late nineteenth century. Even before the railroad connected the northern region of Jalisco to California at the turn of the twentieth century, people were heading north on foot.

At the turn of the twentieth century, large-scale agricultural production based on unequal power relations between hacendados (owners of hacienda plantations) and indebted campesinos (farmers) established agricultural communities. Campesinos in pueblos surrounding the hacienda often planted and harvested land that belonged to the hacendados or powerful families, known as caciques. In remote localities, very small subsistence-farming communities, known as ranchos, were composed of one or two extended families. In such places, in part due to the neglect of the federal government, most rural inhabitants built modest houses with local materials.

Figure 1.03. Map of the state of Jalisco, showing the capital, Guadalajara, the municipalities of Autlán de Navarro and El Limón, and the pueblo San Miguel de Hidalgo. All three communities have long histories of migration to the United States. Drawn by Chesney Floyd.

Figure 1.04. A modestly scaled remittance house breaks the continuous mud-brick wall of two adjacent houses that defines the street in Mexican pueblos. The gated entry patio introduces the layered, formal threshold typical in the United States to the Mexican streetscape. Photograph by author.

To study the remittance house I focus on San Miguel Hidalgo, a pueblo in the south of Jalisco established before the Spanish viceregal period. San Miguel’s range of building types (from adobe brick huts to lavish remittance houses), its location in a region of Jalisco that has a high emigration rate, and its proximity to the other sites examined in this book contributed to my selection of the site. San Miguel, a pueblo of approximately five hundred inhabitants, was entirely (and remains partially) owned by two caciques. As with many pueblos in Jalisco, San Miguel’s built environment reflects its migration history. The impact of emigration to the United States on the community dates to around 1960.10 Various remittance houses—the types range from one-story cement-block houses to large, ornate mansions—share party walls with preremittance-era adobe brick houses, some of which are hundreds of years old. Although San Miguel is a unique case, it provides information about the remittance house that can be applied across disparate remittance landscapes.11

This study is limited to rural places and to individuals who cross the US-Mexico border and work in jobs that are not related to the illegal drug market. However, remittance houses are not only in rural places. New homes built in midsized and large cities need to be analyzed. So do remittance homes built by migrants who have not necessarily crossed international boundaries. Rural Mexicans who have migrated to Guadalajara sometimes build homes in their pueblos of origin that reflect urban Mexican architectural styles. And finally, remittance capital does not result only from economic migrants working legal and ordinary jobs; remittance capital is also increasingly linked to illicit jobs related to Mexico’s narco-industry.12 Narco-architecture is also funded by capital embedded in distant markets and activities and tied to the political economy of both countries. While remittance architecture is being built in both rural and urban localities, and while distant markets support the production of both migrant remittance homes and narco-architecture, I focus on migrant homes in rural locations where the built fabric was relatively consistent before migration and where remittances mark a radical change in what is possible.

Traditional House Forms in Rural Mexico

In rural Mexico, building an adobe house has traditionally been a communal activity performed by men. Until recently, the principal building material in rural Jalisco was adobe brick—a mixture of earth, zacate (grass), and horse manure. To make adobe brick, laborers worked in complementary ways: one worker’s knowledge of where the tierra buena (good earth) was located was complemented by another worker’s knowledge of brick-drying techniques. Also, the vulnerability of adobe construction to the elements—notably water, wind, and pests—required a homeowner to continuously tend to his house and to rely on his neighbors to keep it in good condition. These processes reinforced ties between individuals and the immediate environment and created an interdependent community.

While most men in the village were known as albañiles (ordinary house builders), some possessed special craft skills: one was able to build roofs and another to craft wooden doors. These specialized skills allowed neighbors to strengthen their standing in the community by extending their help to other families. Similarly, barter produced systems of mutual interdependence in which farm produce could be exchanged for labor and expertise—one farmer’s honey would be traded for another’s time. This pattern of exchange allowed a seemingly homogenous community to articulate important social distinctions.

Traditional dwellings in San Miguel also exhibit a close fit between domestic space and an agrarian way of life. Typical houses consist of a courtyard (or a large enclosed yard) surrounded by inward-facing living quarters and an interior porch connecting private rooms with the communal space of the courtyard. The courtyard, a multifunctional space, is by far the most frequently used area in the house. In the courtyard a large outdoor comal, or wood-burning oven for stewing meat and making bread, a well, and a tub for washing clothes are situated among fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Corrals and stables for livestock, and sheds for tools to make honey or adobe bricks, often constitute an enclosure along one side of the yard. When taken together, these spaces of production allowed families to maintain a level of self-sufficiency.

The exterior wall that encloses the courtyard house also defines the edge of the street. This front wall is fully attached and continuous with neighboring structures, forming an uninterrupted facade. The wall supports a traditional roof known as dos aguas (two waters) covered with clay tile, with a ridge that parallels the street and extends seamlessly from one house to the next. The wall and roof create a continuous fabric that separates public from private space.13

Traditionally, people build and enlarge adobe homes in an incremental fashion. The Rodríguez house, built around 1930, exemplifies this incremental, informal approach to the construction of domestic space. Originally a one-room dwelling, the enclosed space consisted of a communal sleeping area attached to a large unfenced yard. Adults slept on the dirt floor, while wooden boards that rested on the wooden roof beams created a tiny (and dangerous) atticlike space for their seven children to sleep next to piles of corn. During the dry months their five boys slept outside. About twenty years later the family added two additional rooms to provide separate sleeping quarters for boys and girls. Shortly thereafter they extended and enclosed the long veranda or patio on the cour...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Remittance Space

- 1 The Remittance House

- 2 Tres por Uno

- 3 El Jaripeo

- 4 La Casa de Cultura

- 5 In Search of a Better Death

- 6 Migrant Metropolis

- Conclusion: Rethinking Migration and Place

- Notes

- Index