- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

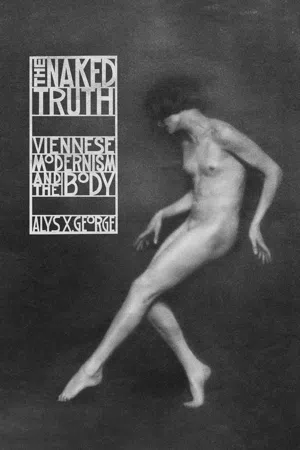

Uncovers the interplay of the physical and the aesthetic that shaped Viennese modernism and offers a new interpretation of this moment in the history of the West.

Viennese modernism is often described in terms of a fin-de-siècle fascination with the psyche. But this stereotype of the movement as essentially cerebral overlooks a rich cultural history of the body. The Naked Truth, an interdisciplinary tour de force, addresses this lacuna, fundamentally recasting the visual, literary, and performative cultures of Viennese modernism through an innovative focus on the corporeal.

Alys X. George explores the modernist focus on the flesh by turning our attention to the second Vienna medical school, which revolutionized the field of anatomy in the 1800s. As she traces the results of this materialist influence across a broad range of cultural forms—exhibitions, literature, portraiture, dance, film, and more—George brings into dialogue a diverse group of historical protagonists, from canonical figures such as Egon Schiele, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal to long-overlooked ones, including author and doctor Marie Pappenheim, journalist Else Feldmann, and dancers Grete Wiesenthal, Gertrud Bodenwieser, and Hilde Holger. She deftly blends analyses of popular and "high" culture, laying to rest the notion that Viennese modernism was an exclusively male movement. The Naked Truth uncovers the complex interplay of the physical and the aesthetic that shaped modernism and offers a striking new interpretation of this fascinating moment in the history of the West.

Viennese modernism is often described in terms of a fin-de-siècle fascination with the psyche. But this stereotype of the movement as essentially cerebral overlooks a rich cultural history of the body. The Naked Truth, an interdisciplinary tour de force, addresses this lacuna, fundamentally recasting the visual, literary, and performative cultures of Viennese modernism through an innovative focus on the corporeal.

Alys X. George explores the modernist focus on the flesh by turning our attention to the second Vienna medical school, which revolutionized the field of anatomy in the 1800s. As she traces the results of this materialist influence across a broad range of cultural forms—exhibitions, literature, portraiture, dance, film, and more—George brings into dialogue a diverse group of historical protagonists, from canonical figures such as Egon Schiele, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal to long-overlooked ones, including author and doctor Marie Pappenheim, journalist Else Feldmann, and dancers Grete Wiesenthal, Gertrud Bodenwieser, and Hilde Holger. She deftly blends analyses of popular and "high" culture, laying to rest the notion that Viennese modernism was an exclusively male movement. The Naked Truth uncovers the complex interplay of the physical and the aesthetic that shaped modernism and offers a striking new interpretation of this fascinating moment in the history of the West.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Naked Truth by Alys X. George in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780226819969, 9780226669984eBook ISBN

9780226695006Chapter One

The Body on Display: Staging the Other, Shaping the Self

The postal ship arriving from Budapest on the afternoon of July 10, 1896, docked at the Weißgerberlände on the Danube canal in Vienna’s third district. Local newspapers had been trumpeting the ship’s arrival days in advance, and a crowd over two thousand strong turned out to welcome the vessel. Journalists from the Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, and other dailies were on the scene that day and reported how, with “thunderous jubilation, like at an electoral victory,” the throngs cheered the visitors and surged toward the quay, each person straining to catch a glimpse of the disembarking party. The police, anticipating such a commotion, had fenced off and restricted public access to the landing earlier in the day. Despite their best efforts, though, the authorities could maintain crowd control only with great effort.1 What could have incited the normally decorous Viennese to such feverish anticipation? The arriving contingent consisted of close to seventy natives from Africa’s Gold Coast, and the Extrablatt’s writer remarked that the Viennese people “would have lifted the black people onto their shoulders if they could have.”2 “Ashanti fever” had gripped Vienna.3

The thirty men, eighteen women, and twenty children4—purportedly members of the Ashanti people of what is today south-central Ghana—had arrived to take part in the latest in a series of so-called ethnographic or anthropological exhibitions, also known as Völkerschauen (shows of peoples), and which I will refer to here as human displays.5 The human display was a form of popular entertainment that became ever more fashionable in Europe around the turn of the century. Vienna alone was host to more than fifty such exhibitions between 1870 and 1910, averaging more than one per year for forty years straight.6 Audiences likewise swarmed to another kind of exhibition staged after the turn of the century, with increasing frequency into the interwar years: hygiene exhibitions. Both trends hinged on the public staging and display of the human body for consumption and comparison. While human displays profited from exploitation and voyeuristic spectatorship in their stagings of the “exotic” body of the cultural Other, hygiene exhibitions trafficked in knowledge about the bodily Self. Despite their marked differences, both phenomena posited surprisingly homologous utopian concepts of “natural” and “authentic” living and “natural” and “ideal” bodies, which acted as foils for the anxieties of modern society.

Advances in medicine and hygiene in the second half of the nineteenth century had afforded people lives that were healthier and longer than ever before. The popularization of discoveries from the life sciences and medicine gave more and more Austrians knowledge about their bodies, allowing them to reflect on and tailor their lifestyles to achieve improved health and longevity. While modernization and scientific progress certainly bettered the lives of many, the heightened attention to individual and social disciplining of the body also revealed a gap between physical ideals to be striven for and people’s corporeal realities. The longing of an entire generation for “new men” and “new women”—in short, for a modern human being, who became a paradigm of twentieth-century revolutionaries, reformers, and dictators alike—necessitated a new relationship with the body and new discourses of the body.7 At work here is a process of identity construction, both individual and collective, a process that occurs through the staging, visualization, and representation of two bodies: the body of the Self and the body of the Other. As this chapter proposes, the shaping of individual and collective corporeal identities commensurate with turn-of-the-century Viennese modernism and modernity at large was played out in the display of human bodies in popular culture.

At work in all of these contexts is a sense of longing—a desire to recover something lost, to make present something absent, or to access something (or someone) forbidden or unapproachable. From their inception, human displays were designed to give the impression of authentic encounter. Just as such exhibitions sold audiences the premise that they were seeing authentic native peoples who live in closer alignment with nature, the life reform and hygiene movement promised physiological optimization—an approach to the body’s “authentic” state—through improved lifestyles. At the heart of this longing, in both cases, is the human body. And the sciences and medicine were, as we will see, deeply implicated in the objectification and instrumentalization of the body—its display, exoticizing, documentation, eroticizing, comparison, and classification—that permeated Viennese life in the decades around the turn of the century. These domains also filtered into Viennese modernism.

Read together, the issues outlined here find a prominent place in the cultural production of one of the leading players in fin-de-siècle Vienna, but one typically read as a quixotic, bohemian contrarian: Peter Altenberg. Altenberg’s oeuvre is a remarkable nexus for the phenomena highlighted above—the vogue for human displays and the life reform movement—as well as for the diverse elements of the cultural discourse of the body around 1900. Perhaps more than anyone else at work in turn-of-the-century Vienna, Altenberg took up Hermann Bahr’s call to engage with the body and create a “new man” to go along with the modernist spirit. In turn, Altenberg’s experiments shed light on processes of personal and collective identity construction through the body in fin-de-siècle Vienna.

Science and Spectacle: “Exotic” Bodies on Display

The jubilant reception that greeted the Ashantis at the Weißgerberlände in July 1896 was crowned by a celebrity parade in typical Viennese style. Fiaker, the horse-drawn carriages so characteristic of the city’s image even today, ferried the participants from the quay to the city center and around the Ringstraße, before arriving at the zoological garden in the Prater park.8 The Ashanti village was very literally a human zoo inside a zoo. There, the “villa colony,” as it was called, consisted of roughly a dozen huts, arranged in circular fashion around an open tract, where it would remain for more than three months.9 While earlier human displays had aroused ample journalistic attention, the Ashanti village’s size, scale, and detail kindled unprecedented public and media excitement. The exuberant crowds that had met the arriving ship turned out en masse for the duration of the exhibition, breaking all prior box office records. Fifteen thousand visitors attended on the opening afternoon alone; for the month of July one hundred and six thousand attendees were counted. On Sundays, the exhibition regularly drew up to thirty thousand paying visitors, and some days were so full that entry had to be restricted.10 Both highbrow Viennese newspapers, such as the liberal Neue Freie Presse, and the popular press kept curious readers current about the daily goings-on at the Ashanti village in great detail. The Neues Wiener Tagblatt and Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, for example, dedicated significant column space to the events. Stories and dispatches—often with prominent front-page or feuilleton placement—appeared nearly every day for the show’s tenure. “‘Ashanti’ has become the ultimate word du jour in Vienna,” remarked Robert Franceschini, science feuilletonist for the Neues Wiener Tagblatt. He continued:

It is as if there were only few other interests to be had in Vienna that are more important than a visit to the Negro village. . . . Since the black caravan came here from Budapest, almost only one stereotypical question is heard in public places and when people meet on the street: “Have you been to [see] the Ashantis?” And there is hardly any get-together without the Ashanti village sooner or later being the topic of conversation. The public displays a virtually feverish attention for it, and like people at archery and singing festivals [Schützen- und Sängerfesten], who are happy when they get to shake the hand of an archer or singer, now they are happy when they can sit at a table with Negroes or carry a black child in their arms. Brotherhoods are toasted to, friendships forged, and some European enthusiasts even attempt gallant overtures toward the beauties from the Gold Coast.11

Franceschini’s summary captures something of the enthusiasm the exhibition aroused. Even decades later, the memories of visiting the exhibition remained vivid, as an article from the Arbeiter-Zeitung from 1928 by the journalist Else Feldmann documents.12 While such accounts highlight the Viennese public’s sustained desire for contact with the peoples on display, they do not, for the most part, reflect critically either on how these people came to be on display in Vienna or on their experiences.

The 1896 Ashanti village was an unmatched box office hit, but it was hardly the first such exhibition in Vienna. Human displays date back to the first third of the nineteenth century, and the Ashanti were among the first to arrive in Vienna. In 1833, for example, the Wiener Zeitung ran advertisements announcing an exhibition of “Africans from the warmongering nation of the Ashantis.”13 Beginning in the early 1870s and continuing well into the 1920s and 1930s, a steady stream of indigenous peoples—Sudanese, Swahili, Sinhalese, Zulu, Australian Aborigines, Native Americans, Bedouins, Siamese, Samoans, Burmese, Inuits, American cowboys, and countless others—populated Vienna’s public exhibitions grounds. Exhibitions of this kind were fixtures in the popular entertainment landscape of the 1860s and early 1870s throughout Europe. The German impresario Carl Hagenbeck (1844–1913), however, knew to capitalize on this trend and coined the term Völkerschau to describe the live visual displays of humans that would make him famous. Hagenbeck had already made a name for himself with his family-run animal menagerie and zoological garden in Hamburg by 1875, when he began importing and exhibiting non-Western peoples for “ethnographic” purposes. Traveling performances such as Hagenbeck’s ranged from a single person to ensembles of hundreds, and each exhibition was designed to present a specific geographical region or a particular national, cultural, or ethnic group. The troupes traveled from city to city, appearing at world’s fairs, museums, and other popular entertainment venues across Europe. Most frequently, though, they ended up in zoological gardens like the one in Vienna’s Prater park—which were undergoing a transformation in purpose in the late nineteenth century. Here, entire villages were constructed, complete with dozens of “authentic” huts, places of worship, and ritual grounds for dances and other cultural performances. Often, such native villages were set up alongside sculpted botanical and zoological landscapes that displayed flora and fauna native to the region in question.14

Fig. 4. “The Ashanti Chief with His Royal Court” on display in Vienna, 1897. Wiener Bilder, May 16, 1897, 3. Photographer unknown. ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

The human display craze in fin-de-siècle Vienna and elsewhere can be read in the context of a wider culture of what Vanessa R. Schwartz has called “spectacular realities,” which emerged from and played a pivotal role in the entertainment industry of the late nineteenth century. These included such popular cultural forms as the mass illustrated press, wax museums, dioramas and panoramas, early film, and anatomical, pathological, and ethnographic museum collections, all of which purported to represent contemporary life “realistically,” but in fact relied on sensationalism to reach the broadest possible audiences.15 In Vienna, the majority of human displays were concentrated in the Prater, the park that became a focus of Viennese public life after Emperor Joseph II opened it for general recreation in the mid-eighteenth century. By the late nineteenth century, the Prater—with its central attraction, the Wurstelprater amusement zone, immortalized by Felix Salten in his 1911 book16—had become a “doubly exotic” site of twin spectatorial pursuits: masses crowding the exhibition spaces to catch glimpses of “exotic” peoples; and an educated, bourgeois audience purporting to observe the “primitive” gawking behavior of a broad mass public.17 “Exotic” behaviors and “exotic” bodies alike were the subjects of study.

Among the visitors were not only the usual Prater habitués, the working classes, but also the heir presumptive Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Viennese artistic set, including Richard Beer-Hofmann, Arthur Schnitzler, Felix Salten, and Peter Altenberg, many of whom rendered their encounters in literature.18 Theodor Herzl, for example, expressed amazement about the exhibitions on view in “The Human Zoo” (Der Menschengarten), which ran in the Neue Freie Presse in April 1897. “Well now I have seen everything!” he marveled in the article, whose title is a play on the word Tiergarten (“animal garden,” or zoo). “In the Prater there are any number of ‘wild’ people and animals currently assembled, brought here by entrepreneurs for curious onlookers who could never travel to such faraway places. One sees Samoans, Singhalese, and Ashantis, and in the cages, pens, pits, and enclosures all manner of beasts, worms, and birds. . . . In what forms the species that want to survive take refuge! And what terrors the struggle for survival generates.”19 The liberal Neue Freie Presse—for which Herzl was the Paris correspondent during the Dreyfus affair in the mid-1890s, and of which he ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Translations

- Introduction

- 1. The Body on Display: Staging the Other, Shaping the Self

- 2. The Body in Pieces: Viennese Literature’s Anatomies

- 3. The Patient’s Body: Working-Class Women in the Clinic

- 4. The Body in Motion: Staging Silent Expression

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index