- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

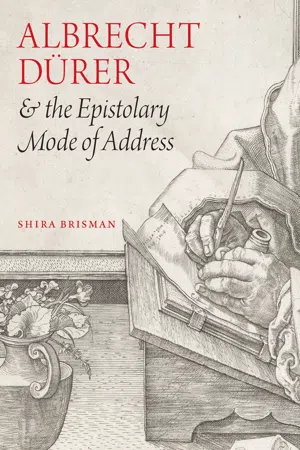

Albrecht Dürer and the Epistolary Mode of Address

About this book

Art historians have long looked to letters to secure biographical details; clarify relationships between artists and patrons; and present artists as modern, self-aware individuals. This book takes a novel approach: focusing on Albrecht Dürer, Shira Brisman is the first to argue that the experience of writing, sending, and receiving letters shaped how he treated the work of art as an agent for communication.

In the early modern period, before the establishment of a reliable postal system, letters faced risks of interception and delay. During the Reformation, the printing press threatened to expose intimate exchanges and blur the line between public and private life. Exploring the complex travel patterns of sixteenth-century missives, Brisman explains how these issues of sending and receiving informed Dürer's artistic practices. His success, she contends, was due in large part to his development of pictorial strategies—an epistolary mode of address—marked by a direct, intimate appeal to the viewer, an appeal that also acknowledged the distance and delay that defers the message before it can reach its recipient. As images, often in the form of prints, coursed through an open market, and artists lost direct control over the sale and reception of their work, Germany's chief printmaker navigated the new terrain by creating in his images a balance between legibility and concealment, intimacy and public address.

In the early modern period, before the establishment of a reliable postal system, letters faced risks of interception and delay. During the Reformation, the printing press threatened to expose intimate exchanges and blur the line between public and private life. Exploring the complex travel patterns of sixteenth-century missives, Brisman explains how these issues of sending and receiving informed Dürer's artistic practices. His success, she contends, was due in large part to his development of pictorial strategies—an epistolary mode of address—marked by a direct, intimate appeal to the viewer, an appeal that also acknowledged the distance and delay that defers the message before it can reach its recipient. As images, often in the form of prints, coursed through an open market, and artists lost direct control over the sale and reception of their work, Germany's chief printmaker navigated the new terrain by creating in his images a balance between legibility and concealment, intimacy and public address.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Albrecht Dürer and the Epistolary Mode of Address by Shira Brisman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Composing

CHAPTER ONE

The Body of a Letter

The experience of writing, sending, and receiving letters shaped how Albrecht Dürer conceived of the message-bearing properties of his works of art. In certain passages, his images offer openly communicative gestures, such as declarative text; at other moments, they suggest but withhold, luring the beholder’s attention toward contents placed at a distance, tucked within a disappearing device such as a closed container, or a page turned away from view. These calibrations of legibility, proximity, and openness are pictorial devices that share traits with the letter, a mode of correspondence that is predicated on distance, prone to delay, and susceptible to receipt by audiences that may far exceed the named addressee. To position his epistolary activities and the postal conditions of his day at intersections with the making, selling, and distribution of his art is to clarify how Dürer advanced the image’s status as an occasion for interpretive reading.

In an example of direct address, Dürer includes a portrait of himself standing amid an imagined gathering that he painted for the Brotherhood of the Rosary, a confraternity of German merchants in Venice (fig. 1.1). Gazing out, he holds a sign, “Exegit quinquemestri spatio Albertus Durer Germanus M.D.VI.” The sheet graphically announces his name, place of origin, and the time it took him to complete the commission. In a manner allusive of the cartellini of Italian painters, the upper edge of the page curls forward, threatening to conceal the words, as if their visibility were a privilege of the viewer’s timely arrival before the image.1 Dürer’s public announcement is made coy by the suggestion of this contingency.

Fig. 1.1. Albrecht Dürer, Brotherhood of the Rosary (detail), 1506. Oil on panel, 162 × 194.5 cm. Prague, National Gallery. Photo: Národni Galerie, Prague, Czech Republic / Bridgeman Images.

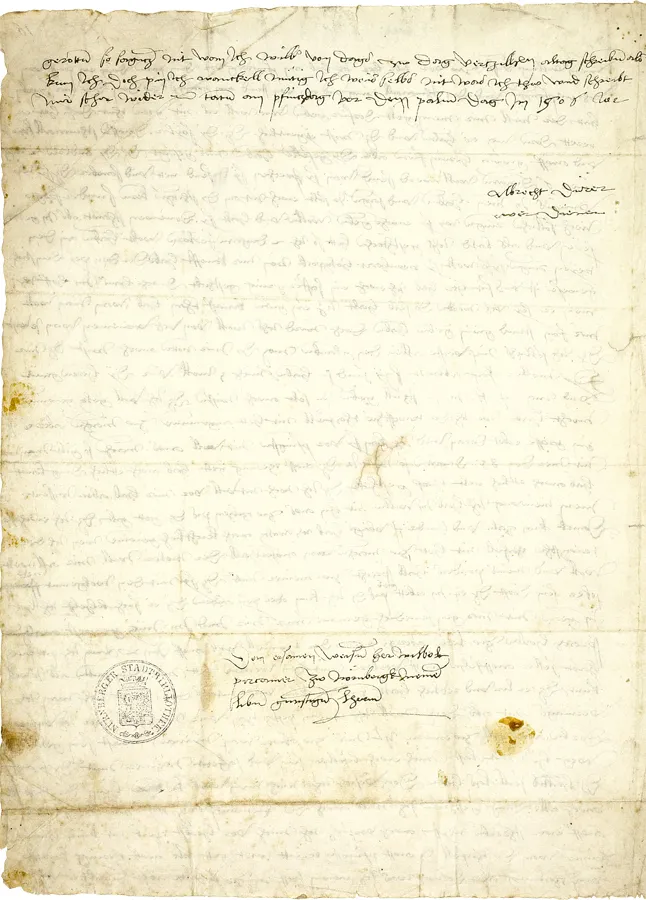

In 1506, the year the painting was made, Dürer was not at home and was doing a lot of writing. Of the many missives that he sent from abroad, ten letters to Willibald Pirckheimer are extant. No replies survive. When composing for his friend, Dürer would fill a page from top to bottom in continuous lines of text without paragraph breaks. A gap between the salutation and the “body” of the letter was a mark of hierarchical discrepancy between the author and the recipient.2 The interval mirrored social distance. Letters to familiars contained no such margin. This convention evokes a rich set of associations for historians of visual art: blank space indicates interpersonal remove, whereas crowded cursive is a mark of intimacy. When he was finished writing, Dürer would tuck the written part inward, allowing the unmarked remainder on the verso to serve as the surface for the address (envelopes did not yet exist).3 When opened, the exterior markings form the bas-de-page (fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. Letter from Albrecht Dürer to Willibald Pirckheimer, April 2, 1506. Photo: © Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg.

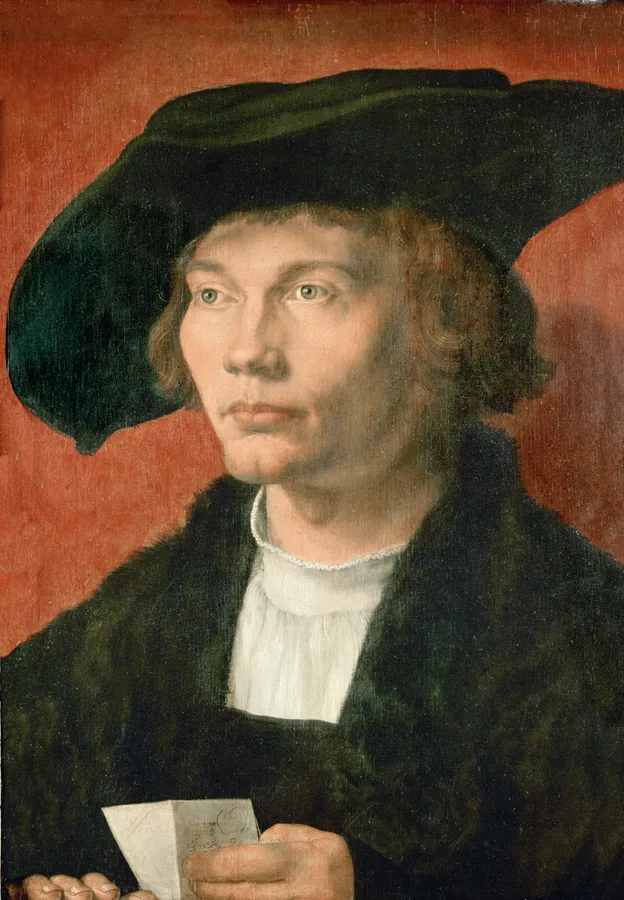

To read a letter, the recipient had to tear a belted strip that had been woven through slits in the page made with a knife or break the seal that fastened folded parts together.4 Hans Holbein alludes to the rupture required to access the interior of a letter in his portrait of the Danzig merchant Georg Gisze (fig. 1.3).5 One of his hands frames the script, while the other rips the page and slips a finger inside. The insignia that sealed Dürer’s letters displayed a pair of open doors, an allusion to the origin of his family name in the word Tür.6 The artist’s heraldic emblem lent a visual pun to the experience of prying open a missive by marking the transition to the interior of a letter with the image of a threshold opened for passage inside.

Fig. 1.3. Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Georg Gisze, 1532. Oil on oak panel, 96.3 × 85.7 cm. Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie. Photo: bpk, Berlin / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie / Art Resource, NY.

The lines along which a letter creases draw boundaries of protected knowledge. The exterior advertises the name of the reader while concealing the contents to which he has access. Portraits from Dürer’s time borrow the analogy of the fold. Gripped in the hands of merchants or kings, letters allow an artist to label his client by subtle means, within the conceits of represented space, at the same time that they hint at the sitter’s possession of information contained within the plicated sheet. The portrait of Bernhard von Resten that Dürer would paint on another journey, his visit to the Netherlands in 1520–21, differentiates what the viewer knows and can see (the external appearance of the sitter, the outer casing of the folded letter) from what the person portrayed possesses (access to content that the painting does not disclose; fig. 1.4).7 The trope of this balance, applied coolly in the work of German portraiture of the early sixteenth century, is pushed to even greater depths in representations that do not necessarily include the motif of the letter, as in the “outward splendor and inner doubt” of Bronzino’s pictures.8

Fig. 1.4. Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of Bernhard von Resten, 1521. Oil on panel, 46 × 32 cm. Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

By fate of their survival over centuries, Dürer’s Venetian correspondences have been scrutinized for biographical information about the artist’s friendship with a leading Nuremberg humanist, his management of monetary and familial affairs from abroad, his comparative statements about the German and Italian members of his trade, and his documentation of the payments that he received from his patrons.9 But readers of Dürer’s letters have also lamented the paltry offerings that they provide, compared with what historians long to know, such as which works of southern art he saw and admired. In 1876 Moriz Thausing published a Dürer letter from April 25 that had been newly discovered. The letter contains a description of a ring that Dürer had previously sent with a letter and an account of the messengers by whom it traveled. Thausing made only the most modest claims about the document’s contribution to Dürer studies.10 In another essay, Alfred Werner expressed regret that the contents of the artist’s letters fail to provide psychological insight: “For nowhere does Dürer talk about himself, about his inner life and feelings, as directly as Vincent van Gogh does [in his letters to his brother]. Unfortunately, too much space is taken up with details about the precious stones and other items Pirckheimer had commissioned Dürer to buy for him at Venice.”11 Instead of lending emotional cadence to his pictures, Dürer’s letters give descriptions of how he has navigated the markets to spend Pirckheimer’s money on requested goods—jewels, carpets, and feathers—and accounts of the messengers he has sent and the dates of the dispatches of his previous missives.

These record-keeping specifics have much to do with how the artist thought about production and conveyance. Anxiety about the efficacies of communication was a part of Dürer’s everyday life. As he wrote, he calculated intervals between transmission and response and expressed concern about receipt when he had not heard back in adequate time. As Pirckheimer’s buying agent in Venice, Dürer learned to bargain in an economy not his own. He waited for replies of whether his acquisitions had pleased. Dürer’s Italian journey was a lesson in preciousness. At the same time that he was shopping for materials that had unique indexes of value, he was learning how southern artists assessed merit in his trade, and he was experiencing, through the writing, sending, and receiving of letters, what contact with another was worth.

The aim of this chapter is to explain the relationship of these ideas and events and, in doing so, to establish the interpretive method that this book as a whole puts forth. In what follows, I propose five examples of how Dürer’s uses of the conventions of letter writing provide a language for describing how his works of art communicate with their audiences.

First Proposal: The Afterlife of an Epistle

Dürer’s private letters initiate acts of communication that will follow the preliminary contact between author and recipient. Through Pirckheimer, he sends letters to be passed on to his mother, as well as tidings to be delivered verbally to other residents of Nuremberg.12 The communicative role of the letter was not restricted to a dialogical model. Rather, letters operated simultaneously to establish intimacy with the named addressee while also launching a series of message transmissions to other parties. Thus, what is often characterized as a literary conceit of humanists’ correspondences—that the address to an individual belied the letter’s true ambition to construct a community of readers—may also apply to epistles in the vernacular that seem to modern readers classifiable as “private.”13

While Dürer was in Venice, Pirckheimer took care of his friend’s family. After Dürer’s return to Nuremberg, the two continued to act as each other’s proxies. A letter composed by Cornelius Grapheus in Antwerp on February 23, 1524, is addressed to Dürer “or in his absence to Willibald Pirckheimer.”14 When the author of a letter wanted to prohibit the circulation of a message, he might entrust the discreet contents to oral recitation by the messenger.15 Grapheus leaves his news unwritten and says that the bearers of the letter will supply the information that he wishes to convey. The distribution of contents between the written portion of a letter and the speaking duties of its courier was a consequence of the proneness of letters to interception during travel and dissemination after arrival.

The interconnectedness of intimacy and repercussive contact provides a context for understanding certain works of art that may seem both to offer a public statement and to serve a restricted audience. The double address can be detected most clearly in Dürer’s printed portraits, where he announces his personal connection to the sitter as well as the image’s commemorative function. A large woodcut of Ulrich Varnbüler juxtaposes in Roman capitals the sitter’s name and the date with a message written in a Fraktur that calls attention to its authorship: “Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg wishes to preserve by this likeness Ulrich surnamed Varnbüler, Chancellor of the Supreme Court of the Roman Empire, and at the same time a distinguished scholar of language, because of his singular affection for him, and also to honor him by rendering this image for posterity” (fig. 1.5).16 This announcement of Dürer’s affections and his declaration of Varnbüler’s public title are presented as if pasted to the backgro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Composing

- Part Two: Sending

- Part Three: Receiving

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index