- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

I Swear I Saw This records visionary anthropologist Michael Taussig's reflections on the fieldwork notebooks he kept through forty years of travels in Colombia. Taking as a starting point a drawing he made in Medellin in 2006—as well as its caption, "I swear I saw this"—Taussig considers the fieldwork notebook as a type of modernist literature and the place where writers and other creators first work out the imaginative logic of discovery.

Notebooks mix the raw material of observation with reverie, juxtaposed, in Taussig's case, with drawings, watercolors, and newspaper cuttings, which blend the inner and outer worlds in a fashion reminiscent of Brion Gysin and William Burroughs's surreal cut-up technique. Focusing on the small details and observations that are lost when writers convert their notes into finished pieces, Taussig calls for new ways of seeing and using the notebook as form. Memory emerges as a central motif in I Swear I Saw This as he explores his penchant to inscribe new recollections in the margins or directly over the original entries days or weeks after an event. This palimpsest of afterthoughts leads to ruminations on Freud's analysis of dreams, Proust's thoughts on the involuntary workings of memory, and Benjamin's theories of history—fieldwork, Taussig writes, provokes childhood memories with startling ease.

I Swear I Saw This exhibits Taussig's characteristic verve and intellectual audacity, here combined with a revelatory sense of intimacy. He writes, "drawing is thus a depicting, a hauling, an unraveling, and being impelled toward something or somebody." Readers will exult in joining Taussig once again as he follows the threads of a tangled skein of inspired associations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Swear I Saw This by Michael Taussig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780226789835, 9780226789828eBook ISBN

97802267898421

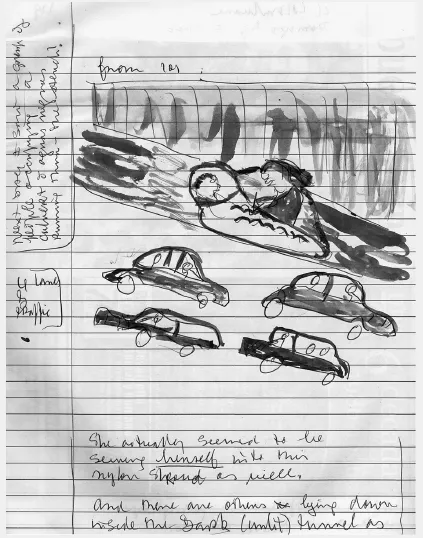

This is a drawing in my notebook of some people I saw lying down at the entrance to a freeway tunnel in Medellin in July 2006. There were even people lying in the pitchblack tunnel. It was 1:30 in the afternoon.

The sides of the freeway before you enter the tunnel are high there, like a canyon, and there is not much room between the cars and the clifflike walls. “Why do they choose this place?” I asked the driver. “Because it’s warm in the tunnel,” he replied. Medellin is the city of eternal spring, famous for its annual flower festival and entrepreneurial energy.

I saw a man and woman. At least I think she was a woman and he was a man. And she was sewing the man into a white nylon bag, the sort of bag peasants use to hold potatoes or corn, tied over the back of a burro making its way doggedly to market. Craning my neck, I saw all this in the three seconds or less it took my taxi to speed past. I made a note in my notebook. Underneath in red pencil I later wrote:

I SWEAR I SAW THIS

And after that I made the drawing, as if I still couldn’t believe what I had seen. When I now turn the pages of the notebook, this picture jumps out.

If I ask what grabs me and why this picture jumps out, my thoughts swarm around a question: What is the difference between seeing and believing? I can write I Swear I Saw This as many times as I like, in red, green, yellow, and blue, but it won’t be enough. The drawing is more than the result of seeing. It is a seeing that doubts itself, and, beyond that, doubts the world of man. Born of doubt in the act of perception, this little picture is like a startle response aimed at simplifying and repeating that act to such a degree that it starts to feel like a talisman. This must be where witnessing separates itself from seeing, where witnessing becomes holy writ: mysterious, complicated, powerful. And necessary.

Looking at this drawing, which now surpasses the experience that gave rise to it, my eye dwells on the mix of calm and desperation in making a shelter out of a nylon bag by the edge of a stream of automobiles. I am carried away by the idea of making a home in the eye of the hurricane, a home in a nation in which it is estimated that close to four million people or one person in ten are now homeless due to paramilitaries often assisted by the Colombian army driving peasants off the land. If you consider just the rural population, which is from where most of the displaced people come, the figure is more like one in four, such that by October 2009, an estimated one hundred and forty thousand people had been murdered by paramilitaries.1

I might add that of all the large cities in Colombia, Medellin is, to my mind, the most associated with paramilitaries. There is a magnetic attraction between the two, and it is not by chance that in this city in particular I would witness the attempt to make a home in this freaky no-man’s-land on the side of the freeway.

Three years after I saw these people by the freeway tunnel, the BBC reported in May of 2009 that soldiers in the Colombian army were murdering civilians and then changing the clothes of the corpses to those of guerrilla fighters so as to boost their guerrilla “kill count.”2 Newly applied free-market policies in the army reward individual soldiers with promotions and vacations according to the number of “terrorists” they kill. They get new language as well, the corpses being referred to by the army and its critics as false positives. The current president, Juan Manuel Santos, was the person overseeing this program in his capacity as minister of defense. He was elected by a landslide in June 2010.

The BBC report claims that 1,500 young men have been killed this way, with more cases being notified daily. Most of them occur in the province of Antioquia, the capital of which is Medellin. “It is alleged that soldiers were sent to the city of Medellin to round up homeless people from the streets who were later presented by the army as rebels killed in combat.”3

They have no land but no-man’s-land.

Once there was forest. They cleared the forest and grew plantains and corn. Then came the cattle. Everyone loves cattle. There is something magical about cattle. From the poorest peasant to the president of the republic, they all want cattle and they always want more—more cattle, that is. The word “cattle” is the root of capital, as in capitalism. The communist guerrillas saw their chance. They started to tax the cattlemen, and in retaliation the cattlemen hired killers called paramilitaries to clear the land of people so as to protect their cattle and then their cocaine-trafficking cousins and friends and now their plantations of African palm for biofuel as well. Before long they owned a good deal more than that. They owned the mayors. They owned the governors of the different provinces, they owned most of Congress and most of the president’s cabinet. The just-retired president of the republic comes from Medellin, and he too is a noted cattleman, retiring to his ranch whenever possible, to brand cows. Imagine a cow without a brand, without an owner! Running free in no-man’s-land!

Once there was forest. Now there is a nylon bag.

The one hundred and forty thousand poor country people assassinated by paramilitaries, recruited and paid for by rich landowners and businessmen, must have known they were dying in a good cause, if the virulent antiterrorist rhetoric of the president of the republic from 2002 to 2010 is anything to go by. That was President Alvaro Uribe Vélez, recipient of a Simón Bolívar Scholarship from the British Council and a nomination to become a senior associate member at the St. Antony’s College, Oxford, doubtless for his scholarly acumen. As governor of Antioquia before he became president for an unconstitutional two terms, he fomented Convivir, one of the first paramilitary groups in Colombia and certainly one of its largest. Close to the entire populations of villages have been massacred by paramilitaries these past twenty years while the army looked the other way or else supplied the names and photographs of the people to be tortured and killed and have their bodies displayed in parts hung from barbed-wire fences. The people of Naya were taken out by machete. The priest of Trujillo was cut into pieces with a power saw. The stories are legion. President Uribe was given the Medal of Freedom by another president, George W Bush. Otherwise it’s a nice enough place, like anywhere else with people adapted to an awful situation like the proverbial three monkeys. I ask a poet from Equatorial Guinea who has been in Colombia twenty years what’s it like back there in that dreadful African country with its thirty plus years of dictatorship. What happens to the mindset of the people? A naïve question, no doubt. “Look around yourself right here in Colombia!” he replies. For any moment you too could answer the phone and receive an amenaza—a death threat—because of your big mouth, your involvement in what is identified as proguerrilla activity, your raising issues of human rights or giving a student a low grade. And why are you complaining?

Somewhere, somehow, real reality breaks through the scrim. It is speaking to you at the other end of the telephone.

There are other moments like that, small and intimate and hardly worth mentioning or measuring. They hold you transfixed. Think of the people lying by the freeway tunnel in Medellin as the taxi hurtles past, a transit both ephemeral and eternal.

What I see also is an unholy alliance or at least symmetry between the enclosed space of the automobiles rushing into the tunnel and the nylon cocoon into which the woman seems to be sewing the man. The automobile offers the fantasy of a safe space in a cruel and unpredictable world, a space of intimacy and daydreaming. Yet the automobile is also a hazard, a leading cause of death and disability in the third world. As against this, consider a home on the freeway made of nylon bags, a home that takes the organic form of the insect world, like the cocoon of a grub destined to become a butterfly.

In this vein I also discern a fearful symmetry between the nylon cocoon and the steep concrete walls adjoining the unlit tunnel of the freeway. When I ask the taxi driver why people would choose to lie there, and he responds, “Because it’s warm,” my question assumes the sheer unfathomability, the impossibility of imagining that human beings would choose such a place to lie down in the same way as you or I lie down in our bedrooms. My question already has built into it my fear and my astonishment that people would choose such radical enclosure. Why would you put yourself into this concrete grave? And his response, “Because it’s warm,” suggests that it has been chosen because of its embrace.

As I dwell on these thoughts I suspect that this hideous location is chosen because it is hideous and, what’s more, dangerous. There, at least you are probably safer from attack by police, death-squad vigilantes, and other poor people.

Then there is that other type of enclosure, the one that grabs me most, that part of the picture in which the woman seems to be enclosing herself as well as the man. Stitch by stitch the outside is becoming the inside. The stitcher becomes the stitched. I am reminded of that little boy years ago in a funeral service in Bogotá who said, “I want to live in a closet.” His parents were research sociologists working for the Jesuits in Bogotá, gathering and publishing statistics on political violence. They were assassinated in 1997 late at night in their bedroom by paramilitaries. The boy escaped by hiding in a closet.

All of this comes to mind when I ask myself why I drew this scene and why this drawing has power over me. But I feel something is missing in what I have said or in the way I am saying it, something that undoes or at least alters meaning along the lines of what Roland Barthes rather dramatically called “the third meaning.” You’ve heard of the third eye and the third man. Now you’ve got the third meaning!

Barthes was a restless thinker. No sooner had he gotten things squared away with his semiotic theory than he found exceptions to the theory because the very act of squaring things self-destructs. What is called “theory” gives you insight. But it does so at the expense of closing off things as well. Theory can never do justice to the contingent, the concrete, or the particular.4 Yet if you don’t exercise that theory muscle to the extent that you realize its limits, then you won’t get to that cherished Zenlike moment of the mastery of nonmastery.

Yes! Barthes saw what he called the “information” in any given image. Yes! He saw what he called the symbolism, too. But nevertheless he became painfully aware of the shortfall between all of that and something else this act of interpretation created. “I receive (and probably even first and foremost) a third meaning,” he wrote, “evident, erratic, obstinate.” What’s more, he spoke of being “held” by the image and that to the extent that “We cannot describe the third meaning . . . I cannot name that which pricks me.”5 Quite an admission.

Is that how a talisman works, I wonder, setting traps made of third meanings? The dangerous spirits out to get you are deflected by the design that is the talisman, kept busy trying to figure out the meaning but cannot. Their mistake. And one we repeat endlessly ourselves, too.

Third “meaning” is not really a meaning at all, but a gap or hole or hermeneutic trap that interpretation itself causes while refusing to give up the struggle. As such, the third meaning has an awful lot to do with the frightening yet liberating sense of enclosure as the last gasp of protection in a heartless world hell-bent on apocalypse as it roars into the tunnel of no return.

My eye fixes on the woman—if she is a woman—sewing herself into the nylon bag. And there’s the stillness. Barthes recalls Baudelaire, who wrote of “the emphatic truth of gesture in the important moments of life.” That is how I think of this woman’s gesture, or should I say how I think of my drawing of such in which what appears as the edge of the bag as a firm blue line encloses the sewer herself. That is my gesture.

But let us for the moment remember that this is only half my story. The other half is the act of making the image. My picture of the people by the freeway is drawn from the flow of life. What I see is real, not a picture. Later on I draw it so it becomes an image, but something strange occurs in this transition. This is surely an old story, the travail of translation as we oscillate from one realm to the other. This is what Genet was getting at when he wrote, “Put all the images in language in a place of safety and make use of them, for they are in the desert, and it’s in the desert we must go and look for them.”6 Thus Genet, the writer, enamored of images that were not really images but words. Where do such images exist then? They must exist between and within the words, on another plane, which we might as well call the desert, perhaps in the oases in the desert, as when Barthes refers us to carnival.

In an attempt to get across its skittishness, Barthes places his third meaning in the realm of puns and jokes and “useless exertions indifferent to moral or aesthetic categories,” such that it sides with “the carnival aspect of things.” To me, the woman sewing, apparently indifferent to the danger around her, can be equated with the realm to which Barthes points. But the carnival lies elsewhere.

For all his originality, Barthes can be seen as drawing upon an older tradition, that of surrealism, as espoused and articulated in 1929 by a German émigré living in Paris, Walter Benjamin, for whom surreal meaning has everything to do with the carnival dance of image and word. Surrealism, he said, takes advantage of the fact that life seemed worth living nowhere but on the threshold between sleeping and waking, across which, back and forth, flood multitudinous images. In this threshold situation, language opens up such that “sound and image, image and sound, interpenetrated with automatic precision and such felicity that no chink was left for the penny-in-the-slot called ‘meaning.’”7

Like the threshold to the Medellin tunnel where the homeless lie midway between sleeping and waking, the threshold of the surrealists between sleeping and waking is quintessentially urban, as when Benjamin writes of the “crossroads where ghostl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Afterthoughts

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index