![]()

ONE

Skilled Visions: Toward an Ecology of Visual Inscriptions

CRISTINA GRASSENI

A large part of ethnographic research, of theoretical reflections, and of commonsense assumptions about vision presumes that those who see are individual spectators and/or social actors, who impose certain social representations on experience. The “skilled visions” approach considers vision as a social activity, a proactive engagement with the world, a realm of expertise that depends heavily on trained perception and on a structured environment. This concept of, and approach to, vision allows us to recontextualize the critique of visualism in the wider contemporary debate on the anthropology of practice and the construction of knowledge.

Introduction

This chapter proposes a survey of some of the approaches to visuality that proliferate at the margins and across the disciplinary boundaries of visual anthropology. It seeks to explain how they contribute methodological tools and insightful case studies that help in charting influences and intellectual hybridizations on and around the history of visual anthropology. In particular, I shall refer to the “skilled visions” approach in the anthropology of vision (Grasseni 2007b), to ethnomethodological studies of visualization in scientific practice (Lynch 1985, 1990, 2001; Lynch and Woolgar 1990), and to Latour’s actor-network theory (1991)—in particular, his approach to visualization and cognition (1986). I shall also draw on cultural psychology and the study of the role of artifacts in communication and cognition (e.g., Hutchins 1986, 1993, 1995; Hutchins and Klausen 1998; Suchman 1987, 1998; Suchman and Trigg 1993). I shall highlight the convergence of visual analysis and discourse analysis, especially in the work of Charles Goodwin (1994, 1996, 1997, 2000; Goodwin and Goodwin 1998; Goodwin and Ueno 2000). I shall argue that these trends are interesting to visual anthropologists as they converge toward a notion of vision that investigates it as the action of a body in an environment, considering it as a form of practical, emotional, and sensual knowledge and privileging case studies that deal with apprenticeship, training, and routines of action.

The aim of this chapter is thus to propose a theoretical approach to the field of “visual anthropology,” which not only interprets it as the study of visual and pictorial culture but poses the question of an “anthropology of vision” as a field of inquiry worth investigating through ethnographic means and methods. In order to roughly define these “strategies of the eye” (Faeta 2003), I propose the following preliminary considerations, which I will elaborate in the following section: First, looking is a technique of the body (Mauss 1935/1979); as such it is culturally inculcated and socially performed as habitus (Bourdieu 1972).1 Second, learning how to look at the world, or how to visualize particular objects or phenomena, is a form of social apprenticeship. Learning a skilled way of looking, therefore, involves senses and emotions as the apprentice becomes proficient in carrying out a form of expertise. Third, the concepts of apprenticeship and of culturally competent ways of seeing lead the ethnographer to keep an analytical focus on different types of “schooling of the eye,” or schools of seeing—for lack of a better word to translate scuole dello sguardo, literally “schools of gaze.”

In alluding to the “gaze,” I by no means mean to invoke a disembodied or abstracted way of looking; I am instead seeking to define an intent and skillful capacity for looking, which I have named elsewhere “skilled vision” (Grasseni 2004a). Schooling of the gaze, in this sense, permeates every aspect of our daily, professional, artistic, and emotional lives. As a result, an anthropology of the visual is not exhausted solely by the production, utilization and cultural analysis of audiovisual, digital, or multimedia texts but includes, too, a close ethnographic analysis of the contexts and protagonists of the schooling of the eye.

As a way of anticipating what is meant here by an “ecology of visual inscriptions,” I refer mainly to the recent trend in ecological anthropology (Ingold 2000), which owes much to some key notions of ecological psychology, such as that of affordance (Gibson 1979), and to the study of perception and cognition as participatory and embedded. By that I mean a situated action performed in a guiding, structured environment (Rogoff 2003; Suchman 1987). If vision is to be explored as a situated practice, it will be of paramount importance to single out the constraints and possibilities offered by the material and social environment that structures visual practice (Ceruti 1986), in terms both of the artifacts employed to guide and channel it, and of the cognitive interactions and communications that help one to attune one’s perceptions and actions to those of others in the same environment.

Exploring Vision as a Situated Practice

The misconception that visual anthropology is exclusively concerned with producing or analyzing images (whether filmic, photographic, or of other kinds) has led to the rather banal and objectionable distinction between a discipline of words and a discipline of images. On the one hand, texts would be both capable of and passively open to transparent analysis, objective critique, and exhaustive description, while images would be opaque, affording too many opportunities and possibilities of interpretation. Hence visual texts would be subjective and incomplete.

Without wishing to enter the vexed question of realism versus relativism (Hollis and Lukes 1982; Hacking 1983; Nichols 1991; Winston 1995), let us remember as a commonly held premise that vision is not an automatic, mimetic capacity for crafting “copies” of things, processes, and images—which must have important implications for the ways we practice visual anthropology, and anthropology tout court. Visual knowledge should not be interpreted as a “realist” adequatio intellectus ad rem but rather as a form of cultural construction of the world around us. This is just one possible way of posing “the epistemological question” in visual anthropology: How do we consider our representations of the world as valid?

I agree with Tim Ingold (1993c, 2000), that we should not think of looking as just a capacity for image-reading or for discerning a predetermined design already present in nature (2001). I would like to discuss here the possibility of carrying out an ethnographic analysis of ways of seeing which, in my interpretation at least, cannot be disjointed from specific ways of looking. This will lead me, in the following section, to consider some responses to the “epistemological question” within neighboring disciplines, such as the anthropology of science, that can be particularly relevant to an anthropology of vision, albeit not devoid of problematic aspects.

In a project that I have carried out in the last few years I have asked fellow anthropologists and professionals from other disciplines to contribute case studies of the ways in which people actually use their eyes.2 I shall quote some of these examples in order to highlight what I mean by “skilled vision” and to explain how this notion may contribute a relativist, constructivist, and ecological solution to the epistemological question in visual anthropology.

The idea was to situate vision in a scenario of everyday skilled activities and to underline both the social and the material dimensions of visual training. Gathering different “ethnographies of sight” led to the conclusion that there is no “vision” as such; instead there are professional, aesthetic, ecstatic, sensual, and erotic exercises of vision, each a skilled and social activity in itself. Consequently, I have proposed the notion of “skilled visions,” in the plural, to acknowledge a plurality of visual practices that employ different kinds of gestural competence, develop within different kinds of apprenticeship, and are differently embodied (Grasseni 2007c). Examples of visual training in high- and low-tech practices (from architecture to urban planning, from scientific laboratories to medical training, from botanical to artistic apprenticeship) stress the importance of local rules and highlight the processes by which consensus on notions of beauty, propriety, and exactness is achieved socially.

This opens up an important aside, which I shall not follow up here but which is worth considering as part of the issues framing the epistemological question, that is, the relation between power and knowledge. A critical focus on imaging technologies—meant as mediators of meaning, power, and knowledge—frequently leads to an often implicit equation between vision and the disembodied, abstracted and rationalizing ways of seeing. From the point of view of the rediscovery of the senses, of the body, and of the local dimensions of knowledge, “visualism” stands for the technification of seeing, for the global inculturation of shallow media images and for the loss of the capacity to “look for oneself.”3 To this, we can oppose two orders of considerations.

First, we are by now used to critiquing Cartesian, formalized, and disembodied forms of visualization as carrying the power of Western rationality or exercising forms of surveillance. But we should remember that the opposite does not necessarily hold: embodied vision is not powerless. On the contrary, the social exercise of sight can be “an activity through which certain social actors find the materials for the maintenance of power” (Herzfeld 2007, 207; see also Herzfeld 2004). For instance, artifacts such as icons, models, and imaging technologies have great importance in inculcating a sense of aesthetic propriety that is seized through the eyes but belongs, in fact, to the visceral, to the core itself of identity—professional and beyond.4 So if vision is cultural, this does not only mean that different cultures hold radically different metaphors for, and hierarchies of, the senses (as the works of Constance Classen and David Howes convincingly demonstrate). It also means that the conditions for the construction of meaningful visual knowledge are local, situated, and contextual—even in the highly technified, standardized, and functional Western world. Some examples from the ethnography of science, in the next section, will substantiate this.

Second, we should consider that visual skill is often invisible! It is a capacity for attention before it can become productive of any kind of visual representation, and, as Brenda Farnell puts it in this volume, “analysis and interpretations must be grounded in the multiple and complex invisible forms of cultural knowledge that make that which is visible and meaningful to its practitioners.” Therefore, we should find appropriate ways of investigating such tacit knowledge in its making, for instance, by studying the material and relational structure of its contexts of production. In the examples that follow, for instance, participant observation, analytic camerawork, and art-historical investigation have been used.

One “learns to see” in cultural ways. Visual training happens within forms of social (and sometimes, but not always, professional) apprenticeship. Francesco Ronzon (2007) elaborates ironically on visual skill from the margins of acceptable theatrical performance, following a group of drag queens acting on stage in the gay clubs of Verona, Italy. He “follows the followers” of Madame Sisi, a well-established drag performer posing particular attention to the artifacts and conversations exchanged by Madame Sisi’s fans. Artifacts such as posters or photographs of gay “icons” support and acknowledge collective notions of “propriety” and “beauty.” Appreciative and critical remarks about each other’s looks further negotiate and contextualize such notions. Here, “skilled vision” is the result of verbal, social, and aesthetic training carried out as resistance in the face of discrimination and marginalization. The ethnographer, newly exposed to this form of life, has to “pick up” the relevant cues in an environment where commonsensical definitions of beauty and grace break down.

A second example uses the technique of the analytic revisitation of filmed images, in time-lapse and slow motion, to highlight cultural patterns of movement. Riccardo Putti (2005, 2008) refers to “cultural kinesics” (Carpitella 1981a, 1981b) to distill the patterned behavior of visitors at an exhibition in Siena dedicated to fourteenth-century Gothic art. In particular, he highlights the widespread use of indexicals and acts of pointing to direct the visitors’ attention, notices that acts of orientation and self-disposition in the space are a fundamental factor in the overall aesthetic experience of the visitor, and underlines a commonality of experience created by the space and rhythm of movement of other people’s bodies in space. He concludes that vision is not exclusively visual but a resonant, kinetic, synthetic mode of perception.

A historical analysis of botanical illustrations in eighteenth-century colonial science confirms this. Daniela Bleichmar has studied how naturalists were trained at length before going to the field, reading authoritative texts, memorizing and redrawing their illustrations. “Seeing was neither simple nor immediate, but a sophisticated technique that identified practitioners as belonging or not to a community of observers” (Bleichmar 2007, 175).5 Bleichmar discusses how “the notion of sight went beyond the physiological act of seeing to involve rather insight—an accretion that the paradox of the blind naturalist brings to the fore. The acumen of observation became so characteristic of the very persona of the naturalist that one could even do without the eyes” (168). To substantiate this claim, she quotes the case of Georgius Everhardus Rumphius (1627–1702), a German botanist and collector employed by the Dutch East India Company, who lost his eyesight.

Despite this considerable challenge, over the second half of the seventeenth century Rumphius amassed an incomparable collection of natural objects, many of which he sold to the Grand Duke of Tuscany as the basis of an impressive natural history cabinet. Rumphius also had many items drawn, and wrote or dictated their scientific descriptions in preparation for publication. These images and texts furnished the material for two titles appearing posthumously over the first half of the eighteenth century, The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet (1705) and The Ambonese Herbarium (1741–55). (167)

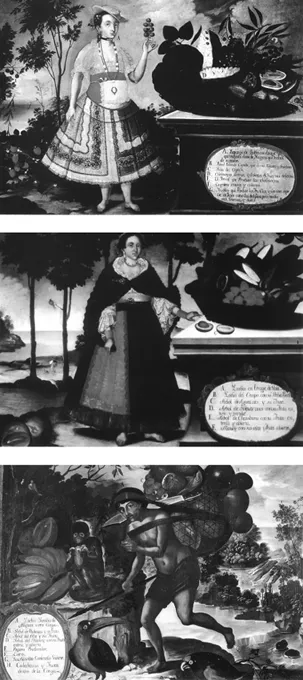

Bleichmar argues that it was the authority of this kind of skilled vision that was implicitly drawn upon, when organizing and producing completely different kinds of representation of local knowledge, namely taxonomies of race ordered by degrees of miscegenation. Casta paintings of the late eighteenth century typically compiled model images of individuals or couples of different ethnicities, according to a white-to-black gradation correlated to occupation, social standing, and disposition. The ideological nature of this kind of taxonomic enterprise stands out glaringly now. What I wish to stress here is that it was a form of figurative display of a shared and implicit visual knowledge about “race.” The taxonomic classification and the diagrammatic disposition in space added to the analytical nature of such display (figure 1.1).

1.1 Vicente Albán, Cuadros de mestizaje, six pieces (Quito, 1783). Courtesy of the Museo de América, Madrid.

The final example highlights the enduring guiding influence of structured environments and cultural artifacts for the social inculcation of skilled visual tasks. I refer to my own study of breeding “aesthetics”—the educated capacity of perceiving the animal body in terms of functional beauty—among dairy breeders in particular (see Grasseni 2005a, 2005b). The ethnography was conducted among breeders of the Italian Brown, a milking cow “progeny” breed developed through artificial insemination and intensive inbreeding from the original Swiss Brown breed. Professional breeders learn to look at cows and appreciate their “beauty” in highly functional terms. They assess, by looking, which desirable “milking” traits have been developed, and to what degree, in any single cow. In order to understand how this sensibility is developed, we need to look at what Bruno Latour (1986) would call “the socio-technical system” of animal husbandry: that is, at the interactions between breeders, cows, and the artifacts that mediate their mutual perception. Among the children of breeders, for instance, toys play a transparent role in the social mimicry of adult expertise. Plastic toys mimic the ideal of good form that is found in champion specimens (Grasseni 2007c, 47–66), recalling in detail the “morpho-functional” traits that are evaluated favorably in both cattle fairs and inbreeding practices (see figure 1.2). By observing daily such icons of animal “perfection,” the breeders’ children incorporate them into their everyday ecology of attention.

The use of such toys parallels the cognitive and social role played by scale models of “ideal cows” in the settings of their parents’ professional life. Scale models of prize cows serve, in fact, as trophies at cattle fairs. They are exhibited both in domestic and in professional contexts, thus serving both an educational purpose and one of social acknowledgment. Toys and trophies recapitulate both the historical development and the social inculcation of a professional aesthetics (Grasseni 2004a). This case study shows that what are or are not deemed to be “good looking” animals is often a question of how you learn to look at them. Which kind of visual training one is exposed to is often a case of professional history and of social hegemony. In this case the model Brown cow, mimicked by the plastic toy and the cattle fair trophy, is associated with a recent history of intensive dairy farming and with the ideological promotion of pure breeds with specialized functions.

The point of this ethnography was to stress the convergence of intellectual interest in cognitive artifacts—such as models and diagrams—with the practical concerns of technologies of power and simplification. This could not be cleare...