- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Jazz Age. The phrase conjures images of Louis Armstrong holding court at the Sunset Cafe in Chicago, Duke Ellington dazzling crowds at the Cotton Club in Harlem, and star singers like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. But the Jazz Age was every bit as much of a Paris phenomenon as it was a Chicago and New York scene.

In Paris Blues, Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. He pinpoints key issues of race and nation in France's complicated jazz history from the 1920s through the 1950s. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet, among others—what he asks is how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Fry focuses throughout on early jazz and swing but includes its re-creation—reinvention—in the 1950s. Along the way, he pays tribute to forgotten traditions such as black musical theater, white show bands, and French wartime swing. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and contributes greatly to a growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France.

In Paris Blues, Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. He pinpoints key issues of race and nation in France's complicated jazz history from the 1920s through the 1950s. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet, among others—what he asks is how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Fry focuses throughout on early jazz and swing but includes its re-creation—reinvention—in the 1950s. Along the way, he pays tribute to forgotten traditions such as black musical theater, white show bands, and French wartime swing. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and contributes greatly to a growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paris Blues by Andy Fry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rethinking the Revue nègre

Black Musical Theatre after Josephine Baker

“Keepin’ It Real”: Bamboozled in Paris

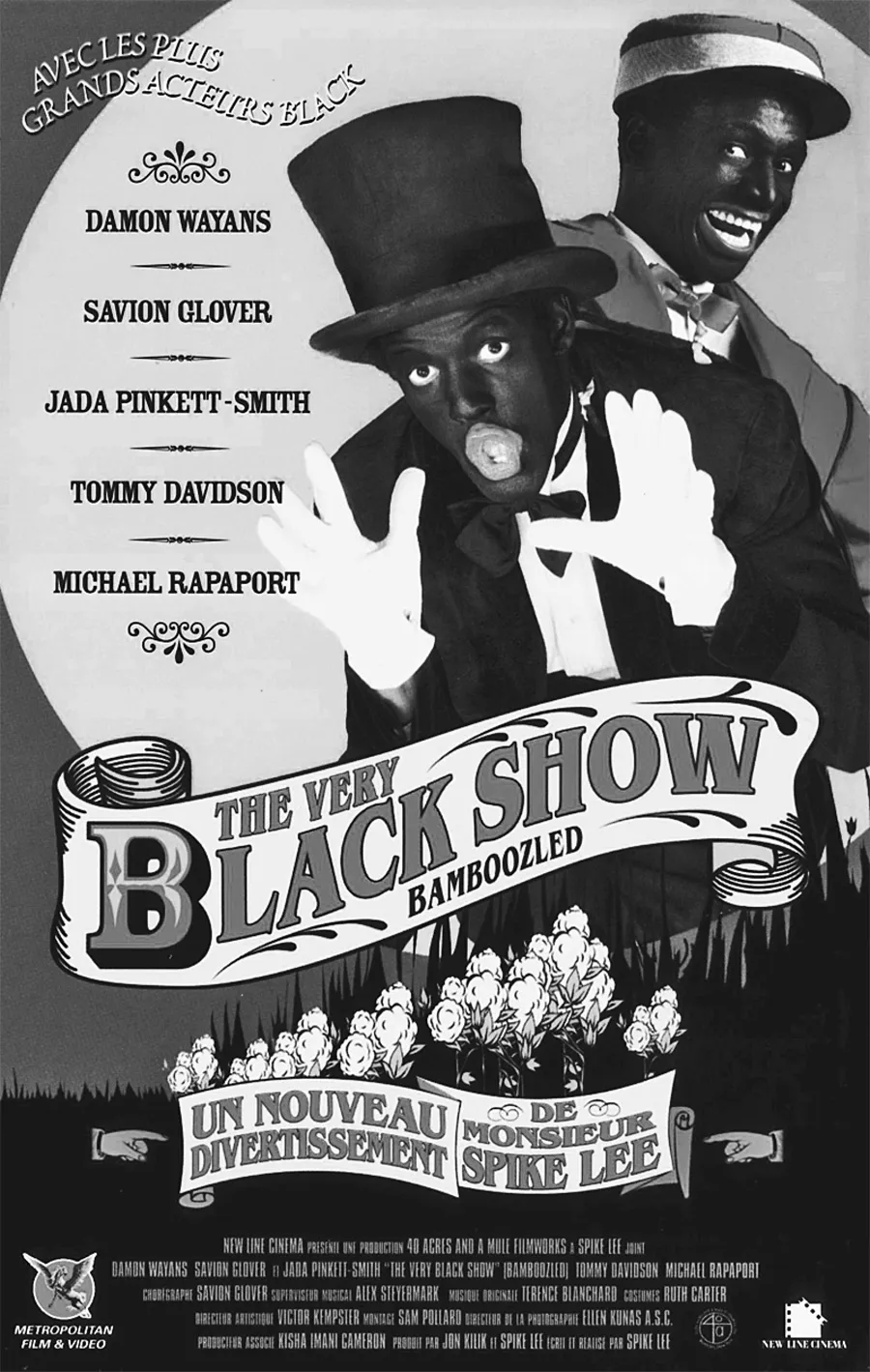

Arriving in Paris one spring, early in the research for this book, I had a peculiar experience. As I thumbed through the week’s entertainment listings in Pariscope, eager for a distraction from apartment hunting, two men in blackface stared out at me (fig. 1.1). They were presenting The Very Black Show, as Spike Lee’s film Bamboozled was known in France. This polemic on the representation of African Americans had so far escaped my attention, so its release at the moment I returned to the city to research its history of black musical theatre was unnerving, perhaps even uncanny. Suddenly my subject seemed à la mode.

As its opening lines are anxious to establish, Bamboozled is a satire. Meticulously spoken Negro (his term) TV writer Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) prefaces his desperate attempt to lose an insufferable job at ailing corporation CNS with a definition of that dramatic type. Gone are the days when he would write middle-class dramas and situation comedies that his boss Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport) could call “white people with black faces.” With his “black wife and two biracial kids,” Dunwitty has told Delacroix, “I . . . know niggers better than you”: “Brother man, I’m blacker than you. I’m keepin’ it real. . . . You’re just frontin’, tryin’ to be white.” Under such an edict to dig into his roots, Delacroix will deliver exactly what is expected of him: a very “black” show.

Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show stars two African American street entertainers (tap dancer Savion Glover and comedian Tommy Davidson) whom Delacroix used to pass on his way to work. Renamed after stars of a former era, Mantan (for Mantan Moreland) and Sleep ’n’ Eat (Willie Best’s moniker) revive minstrel routines, complete with chickens and watermelons, in blackface and comic attire. “Two real coons,” they call themselves (in honor of Williams and Walker), from a time when “nigras knew they place” [sic]. The studio audience look around nervously before they applaud; the film viewer’s position is similarly uncomfortable. When I saw it in Paris, the cinemagoers, primarily people of color, first laughed uproariously then gradually fell into silence. As Delacroix asks when told the network had taken his (supposedly satirical) show and “made it funnier”: “Funnier to whom? And at whose expense?”

FIGURE 1.1. French publicity poster for The Very Black Show (Bamboozled), dir. Spike Lee (2000).

While the principal target of Lee’s ire is the white-dominated entertainment industry, which perpetuates racist stereotypes, Bamboozled is by no means singular in its attack. Regardless of his original intent, Delacroix becomes complicit, as does his ambitious assistant, Sloan Hopkins (Jada Pinkett-Smith). She’s a “house-nigger” “working hard for the man on the plantation,” according to her brother Julius, a.k.a. Big Blak Afrika (hip-hop artist Mos Def). But he and his band of quasi-revolutionary gangsta rappers, the Mau Maus, are also ceaselessly lampooned, particularly in their empty-headed song “Blak iz Blak.” While Sleep ’n’ Eat and Mantan throw off success in renunciation of the minstrel mask, the Mau Maus turn words into action and execute Mantan (live on TV and the Internet) for his treachery against the race.1 By now, the viewer might legitimately ask if Spike Lee’s satire has not itself lapsed into stereotype. That, of course, is precisely the point: for African American performers (and directors), minstrelsy is at once an unavoidable, sometimes desirable, reference and a dangerous, often destructive, force.2

My interest in Bamboozled is more than anecdotal. The film asks some important questions that resonate with this chapter. How is “black culture” defined and who may access it? When does “authenticity” become stereotype? To what extent can African Americans control their representation on stage and screen? The history and legacy of minstrelsy is a fraught topic, but one that can now lay claim to a sophisticated literature bridging several disciplines.3 While raising public awareness of these issues, Bamboozled, some complained, failed to distinguish adequately between different contexts and eras: “who did what to whom,” in the words of scholar Michele Wallace.4 If minstrelsy traded in images that today are unpalatable, it did so in myriad circumstances and their politics were not always the same. Particularly at its nineteenth-century origins, it may have challenged social hierarchies as much as consolidated them, and affection as well as animosity drives the stereotypes; at least in part, minstrelsy functioned as a means to critique mainstream society from a position outside of it. The decline from satire into demeaning comedy seems almost to be topicalized, within the film world of Bamboozled, in the fall from grace of Delacroix’s show.

These questions may have been well rehearsed in the American context, but in France they are much less frequently raised. Indeed, it is still fondly imagined in some quarters that African Americans escaped prejudice there and were welcomed by everyone as true artists. While the critical response to Bamboozled in France was mixed, therefore, most reviewers agreed that its relevance to them was limited if not lacking: they distanced the minstrel mask both geographically (a US phenomenon, ignoring the extent to which it had traveled) and historically (a nineteenth-century theatrical tradition, forgetting Bamboozled’s setting in contemporary TV). These “negative and often racist representation[s],” thought one writer, demonstrated “American show business’s shameful past”; they were characteristic in particular of late nineteenth-century minstrelsy.5 Another wondered why Lee rehearsed old grievances rather than taking the next step: the “relative advancement of current practices [mœurs]” would allow him to “mix colors or, better, to ignore them” without risking offense.6 Race, critics seemed to argue, was an American problem, and at that one of the past.

More egalitarian online discussion lists offered contrasting views—ones in which French attitudes were implicated. One writer thought Bamboozled the “best film for all self-respecting blacks to see”; a “lucid critique of the current position of blacks in the Western media,” which was especially relevant “in France . . . where minorities must still caricature themselves to appear on TV.” Another agreed: it represented a profound reflection on “the condition of blacks in France and in the world.”7 The fate of the movie with Parisian audiences, then, comes as little surprise: released in a handful of mainstream houses, it was soon showing in only one, Images d’Ailleurs, “premier espace cinéma black de Paris”—the cinematic equivalent of a ghetto.

Contemporary French representations of people of color are beyond the scope of my project.8 But I do hope to fill one historical lacuna in the Paris reviews: the black shows of the 1920s and 1930s—a time when, the story goes, African Americans were in vogue in France. A scene eventually omitted from the movie might have made the point: a picture of a naked Josephine Baker adorns the wall of Mantan’s dressing room.9 But, a few stars excepted, memories are short; the connection runs much deeper. In fact, the original Mantan, Mantan Moreland, was among the many black entertainers who performed in the French capital during the entre-deux-guerres. Like it or not, the French are implicated in this history, if in different ways to Americans. In this chapter, I study a number of black shows, examining both their production and their reception in Paris in some detail, and endeavoring to understand the dialogue that took place between performers and audience.

Contexts and Controversies: La Revue nègre

One moment in particular was notable by its absence from the Bamboozled reviews: La Revue nègre, Josephine Baker’s first Paris show, in 1925. Assembled in New York by white American Caroline Dudley, an all-black troupe famously performed putative scenes of African American life—“Mississippi Steam Boat Race,” “New York Skyscraper,” “Charleston Cabaret,” and so on—on the stage of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.10 So successful were they that theatre manager André Daven, director Jacques-Charles, and poster artist Paul Colin would all later be eager to claim a formative role. Baker’s biographers have sometimes begun their narratives with La Revue nègre, although it was far from the beginning of her career.11 Writers always give particular attention to Baker and Joe Alex’s “Danse de sauvage,” barely clad, in feathers—the most shocking routine of all. Certain descriptions—André Levinson’s “black Venus that haunted Baudelaire,” Janet Flanner’s “unforgettable female ebony statue,” even Robert de Flers’s “lamentable transatlantic exhibitionism which has us reverting to the ape”—signify an almost apocalyptical moment.12 Less often heard are the reactions of some of Baker’s co-performers, who were “horrified at how disgusting Josie was behaving . . . doing her nigger routine”: “She had no self-respect, no shame,” complained one.13 Acclaim and horror are juxtaposed, even combined, in the reviews: La Revue nègre represented equally “the most barbaric spectacle imaginable” and “the very quintessence of modernism.”14 No account of les années folles is complete without it.

Such is the actual and rhetorical importance assigned to La Revue nègre that it has come to represent both the apex of African American entertainment in Paris and, paradoxically, the crux of a reaction against it.15 As is well-known, the show was the last all-black affair in which Baker performed, and the only one in France. While she moved on to feature as an exotic star at the Folies-Bergère and Casino de Paris, most of the troupe had soon returned home. La Revue nègre thus serves as the mythologized origin of a star who comes to stand for—becomes synonymous with—African American show business in Paris. Typical is a republication of Paul Colin’s 1927 lithograph series, Le Tumulte noir, renamed Josephine Baker and “La Revue nègre.”16 Although it includes several images of Baker, this is not a portrayal of the Champs-Élysées show but a survey of black music and dancing in Paris. More than just marketing, the confusion extends to an introductory essay by Karen Dalton and Henry Louis Gates. Set on a one-track path, they misidentify as Baker the final image, of entertainer Adelaide Hall (about whom more below), and fail to notice that two others are not unknown revelers but familiar figures on the French stage, Joe Alex and Hal Sherman, respectively (the latter was in fact white).17

Worse, if Baker was the only real black star in Paris, as the authors suggest, even her appeal was not to last. While acknowledging the images’ sometimes questionable connotations, Dalton and Gates insist that they represent a last flowering of racial tolerance: an expression, in their words, of “the communal sigh of relief African Americans exhaled” in this “color-blind land of tolerance” where “they could savor the freedom of feeling like a human being for the very first time.”18 They quickly about-face: “This climate of openness would not last, however. Already in 1921, what became known as ‘The Call to Order’ . . . [was] admonishing a return to French ‘classical’ traditions and a rejection of . . . foreign influences. . . . Throughout Europe, resentment mounted. . . . And although the National Socialist party would not come to power in Germany until 1933, the first volume of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf had already appeared in 1925.”19 Here both chronology and geography are distorted in order to locate an incipient conservatism, if not fascism. More judicious but in broad agreement, Jody Blake also thinks La Revue nègre was seminal: it “secured the triumph of African American music and dance and unleashed the backlash against it”; it “gave added momentum . . . to a Call to Order in popular entertainment.”20 Both Blake and other authors find support for this argument in contemporary statements now dismissing jazz by composers such as Da...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Rethinking the Revue nègre

- 2. Jack à l’Opéra

- 3. “Du jazz hot à La Créole”

- 4. “That Gypsy in France”

- 5. Remembrance of Jazz Past

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index