- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For decades, China's Xinjiang region has been the site of clashes between long-residing Uyghur and Han settlers. Up until now, much scholarly attention has been paid to state actions and the Uyghur's efforts to resist cultural and economic repression. This has left the other half of the puzzle—the motivations and ambitions of Han settlers themselves—sorely understudied.

With Oil and Water, anthropologist Tom Cliff offers the first ethnographic study of Han in Xinjiang, using in-depth vignettes, oral histories, and more than fifty original photographs to explore how and why they became the people they are now. By shifting focus to the lived experience of ordinary Han settlers, Oil and Water provides an entirely new perspective on Chinese nation building in the twenty-first century and demonstrates the vital role that Xinjiang Han play in national politics—not simply as Beijing's pawns, but as individuals pursuing their own survival and dreams on the frontier.

With Oil and Water, anthropologist Tom Cliff offers the first ethnographic study of Han in Xinjiang, using in-depth vignettes, oral histories, and more than fifty original photographs to explore how and why they became the people they are now. By shifting focus to the lived experience of ordinary Han settlers, Oil and Water provides an entirely new perspective on Chinese nation building in the twenty-first century and demonstrates the vital role that Xinjiang Han play in national politics—not simply as Beijing's pawns, but as individuals pursuing their own survival and dreams on the frontier.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oil and Water by Tom Cliff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226360133, 9780226359939eBook ISBN

9780226360270ONE

Constructing the Civilized City

I am a constructor (jianshezhe 建设者), and so is my husband. A constructor is somebody who has their own goal, and their goal is very clear, and they relentlessly pursue this goal through their work. . . . A constructor is perfectly happy to contribute all their energies and wisdom to achieving this goal. . . . There are many types of constructors . . . but every constructor’s goal is identical. For example, my parents are bingtuan people, and my husband’s parents are cadres, but we are all constructors. What sort of constructors? Constructors of Korla! Although the work that we do is different, our goal is identical: we all aim to make Korla even better, even more beautiful, even more prosperous and strong. That is a constructor.

Idle people, or people who come to Korla only to play around and make a bit of money, are not constructors. Let’s say somebody from neidi hears that Korla is good fun, so they come here to get a bit of work, and to play in the karaoke bars in their time off. Then they go back home after a year or two, or even less. Did they come to Korla? Yes, they came to Korla. Did they expend effort for Korla? Yes, they expended effort. [However], we don’t call these people constructors—they don’t have the consciousness (juewu 觉悟) of a constructor.

YANYAN, A KORLA BENDIREN, 2009

The title constructor implies entitlement and incites emulation, and is at once broadly attributed, widely claimed, and hotly contested in contemporary Xinjiang. This chapter deals with constructor discourse and the social and physical spaces that it creates—and is created by.

Implicit in much of the state and public discourse on construction is an assumption that the physical labor that a constructor does is part of a deeper and further-reaching project of sociocultural transformation. The stated endpoint of this transformation is a “harmonious” and “modern society”—arrived at through eradication, rather than acceptance, of difference, and molding to a particular statist ideal. The aims of construction in 21st century Xinjiang take the cultural and political aesthetics of the Chinese metropole as their guide. The object of construction here is not just Xinjiang-the-place but also the “undeveloped” peoples and cultures of the borderland: there are intimate connections between social and spatial engineering. Constructors are both inter-ethnic and intra-ethnic civilizers (Harrell 1995).

Constructor discourse is a useful optic through which to view social divisions because individuals and groups define and deploy the term constructor to serve their own interests and the interests of people who are “like them,” or allied with them. Many recent Han in-migrants deploy an ahistorical discourse of inclusion—“we [Han] are all constructors”—that is premised on Xinjiang’s current and continual need of construction. On the other hand, the settlers of the 1950s and ‘60s and their descendants speak a discourse of distinction, explicitly basing their demands for preferential treatment on the contribution that they or their forebears have made in the past. Old Xinjiang people claim and leverage firstcomer status in an attempt to marginalize recent arrivals. This notion—of inherent and justified firstcomer privilege—is “a quintessentially frontier idea” (Kopytoff 1987, 53). The narrator of the epigraph to this chapter, Yanyan, seeks to further narrow the category of constructor by insisting that only those with a certain “consciousness” are deserving of the title, regardless of time of migration. Yanyan is contracted by the local government to deliver compulsory mass lectures on civilization and etiquette to the staff of large government work units, and private companies in the service industry. She thus not only reflects the view of many Han in Korla that the act of construction must be a conscious one, but also shapes it. Without consciousness, the argument goes, they cannot be constructors, and only constructors are entitled to the fullness of state patronage.

Bingtuan Construction

The ever-changing picture of construction in [Xinjiang] is marked with our writing. This is our greatest happiness.

SHANGHAI “SENT-DOWN YOUTH” LEADER (SCMP, #3697, MAY 9, 1966, 27)

The bingtuan claims—for itself and its population—archetypal constructor status. It is a well-supported claim. After 1949, the first group to be spoken about as constructors of Xinjiang were the soldier-farmers of the Xinjiang Wilderness Reclamation Army, the immediate precursor to the bingtuan (see Tian 1953). They were directed in 1950 to “defend the border and open the wasteland” by establishing agricultural colonies in strategic locations in Xinjiang. The victorious Communists saw Xinjiang as a tabula rasa, just as the Qing did before them (Millward 1998, 110). The fact that, at the establishment of New China, Xinjiang was already a diverse and dusty palimpsest of cultures, conflicts, and polities—both imagined and extant—presented no obstacle to this time-honored conceit. It was, after all, the conqueror’s prerogative: each new regime in history has depended on the discursive construction of future potential for its own salvation. Since the bingtuan was formally established in October 1954, its evolution has framed the social, political, and economic milieu of Xinjiang; any understanding of contemporary Xinjiang must take the bingtuan into account.

The bingtuan was the main force behind Han in-migration to and cultural transformation in Xinjiang until at least the end of the Mao era. For example, an estimated 50,000 “sent-down youth” from Shanghai were in Xinjiang by 1965 (White 1979, 505–6), and the number reached 450,000 by 1972, of which at least 160,000 served on “army farms” (Bernstein 1977, 69, 191) that were almost all part of the bingtuan system. The bingtuan today is almost entirely civilian, and is both a SOE group and a parallel “quasigovernment” (zhun zhengfu 准政府) in Xinjiang (Zhou and Chen 2012, 38). It has a population of 2.5 million, 12% of Xinjiang’s population, but it occupies 30% of the arable land of the region. Although the physical spaces that the bingtuan governs are nested within Xinjiang, it has a separate budget, its own police force, and its own court system—a sort of bounded sovereignty.

Internally, the bingtuan is arguably the least reformed physical and bureaucratic entity of comparable scope in China today. The resilience of the organization is related to the fact that it is still seen by the central government as playing an important role in maintaining social and political stability in Xinjiang. In part, this is because the bingtuan’s 94% Han population occupies key peri-urban, rural, and border regions. Moreover, the legal parameters governing this settler population remain different to those that govern non-bingtuan populations throughout the rest of rural China, including Xinjiang. These differential modes of governance result in a significant socioeconomic and politico-legal divide between the bingtuan population (especially the newcomers) and the non-bingtuan population (Cliff 2009).

The bingtuan becomes even more important when studying the personal histories of the Han community in Xinjiang because the bingtuan always has been almost exclusively Han populated and a large proportion of old Xinjiang people were themselves raised on bingtuan farms. Everybody who lives in Xinjiang is, in some way, affected by the presence and past of the bingtuan.

Korla’s initial urban urge came from the bingtuan. When Korla people claim that “before liberation [1949], there was nothing much in Korla, just a dirty little river and a few Uyghur farmers; even the Uyghurs came after the Han started to build the city,” they are claiming constructor status for the bingtuan pioneers. In 1949 Han people amounted to only 1.4% of the population of Korla. At that time, Korla was a small county town of less than 30,000 people. A few small Uyghur villages spread out to the south of the township and were enclosed and somewhat protected by a large bend that the Peacock River makes after it passes the Iron Gate Pass, and before it enters the hard stony desert en route to extinction in the wastelands to the east. After 1955 the in-migration of over 55,000 Han tripled the total population and by 1965 Han people constituted a 56.4% majority (XJ50N 2005, 505). An administrative reshuffle helps to explain this rapid growth: Korla took over from the nearby county of Yanqi as the administrative center for Bazhou in 1960 (Bazhou Government Net 2004) and the bingtuan’s Second Agricultural Division shifted its headquarters to Korla at the same time (Bingtuan Second Agricultural Division 2006).

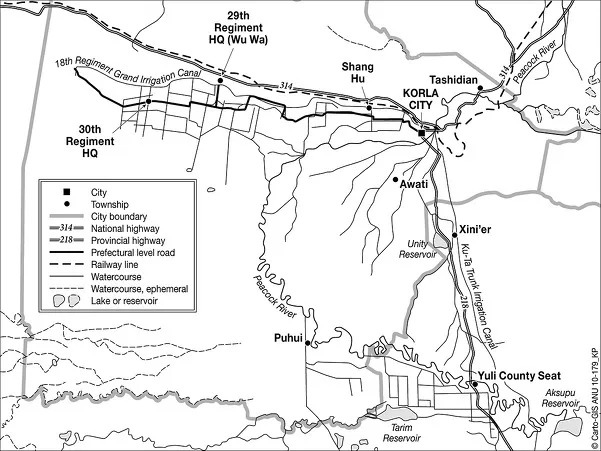

The bingtuan’s unequaled transformative influence on social space and economy in Korla region began, however, during 1950–51 with the construction of the 18th Regiment Grand Irrigation Canal. The 35.2-kilometer-long canal took 7,000 people just nine months to build. In 750,000 person-days, laborers removed 375,000 cubic meters (490,000 cubic yards) of earth and stone. The unlined canal initially flowed at 7.5 cubic meters (9.8 cubic yards) per second and enabled an irrigated area of 50,000 mu (8,330 acres) (Jin 1994, 497).

The 18th Regiment irrigation canal initially reached to Wuwa village on the northern, uphill side of the 18th Regiment. The 18th Regiment was later renamed the 29th Regiment, and Wuwa township now serves as its regimental headquarters. Figure 1.1 (map) shows the geometric organization of space in the newly opened areas associated with the bingtuan—compare the straight outlines of the bingtuan irrigation channels and fields to the scribbly lines of natural seasonal watercourses and the still relatively organic-looking irrigation deltas of the villages (many populated largely by Uyghurs) to the south of Korla. Although these are both recent images, the organization of rural space—land and water resources—shown in them dates from no later than the 1960s. The flat land presented no physical obstacle to the ordered geometric arrangement seen in these images; irrigation enabled large-scale agriculture; Maoist ideology labeled the land as wasteland and positioned nature as an “enemy” to be conquered through violent struggle (Shapiro 2001). For the demobilized soldiers turned bingtuan pioneers, the new “war” was at least as arduous as, and promised an even less-glamorous conclusion than, the civil war that many of them had been fighting for most of their adult life. Subsequent waves of bingtuan settlers, most of them civilian, came to Xinjiang through the 1950s and ’60s as what Mette Hansen calls “subaltern colonisers” (2005, 7). They established their sites of settlement “at the margins of civility” (Workman 1993, 179). In Korla, this meant attempting to farm the salty and inhospitable desert-fringe to the west of what was then a small agricultural settlement and postal waystation. The bingtuan’s survival today depends on convincing funding authorities (the center) of its continuing relevance and thus the necessity of maintaining the institution into the 21st century. In practice, this means demonstrating that it plays an important role in constructing the sacred dyad—“stability and development”—and indefinitely sustaining the notion that Xinjiang is in need of such construction.

1.1 Korla city administrative region map. The irrigation channels of the 29th and 30th regiments can be seen in the top left quadrant of the map. The Uyghur-populated rural areas are south and west of Korla city, around Awati village. Korla city itself is in the top right quadrant.

State Constructor Discourses, 1949–2011

In state terminology, constructor is a flexible and polysemic term, especially when looked at over time. The 135,000 demobilized troops that became the bingtuan have also been referred to as pioneers (chuangyezhe 创业者) (Wang 1985, 2). Since these “reclamation warriors” constituted less than 4% of the total population of Xinjiang at the time and the vast majority of them were Han born outside Xinjiang, (XJSYB 1955–2005, sec. 2-3; Yao and Zhang 2005, 29), it is clear that both constructor and pioneer were culturally specific, even implicitly ethnicized, terms.

Physical construction on China’s borderlands has long been associated with the construction (or realization) of the notion of the Zhonghua minzu (中华民族), a sort of pan-“Chinese” nationalism that takes the Han as the core ethnic group with the most advanced culture.1 In the Republican era, Liang Qichao and others argued “that the unitary yet multi ethnic nature of the Zhonghua minzu was defined by a complex, unfolding national consciousness (minzu yishi)” (Leibold 2011, 347, 358–59). Within the 21st-century PRC geobody, the notion of Zhonghua minzu correlates to territorial and ethnic unity.2 An August 2011 article in the Bingtuan Daily stated, “In the early days of the pioneering bingtuan undertaking, developing Chinese national spirit (Zhonghua minzu jingshen) and revolutionary tradition, and transforming the old rivers and mountains was driven by the pioneers’ own initiative” (Wang L. 2011). The article thus also attributed to the bingtuan pioneers an agency that they did not possess and an ex post facto voluntarism that was seen as lacking at the time. Officers and troops of the 25th Division, for example, spent the first 50 days of 1950 in political study sessions that were aimed at convincing them to accept that they were in Xinjiang, to protect and to construct, fo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Constructing the Civilized City

- 2 The Individual and the Era-Defining Institutions of State

- 3 Structured Mobility in a Neo-Danwei

- 4 Legends and Aspirations of the Oil Elite

- 5 Lives of Guanxi

- 6 Married to the Structure

- 7 The Partnership of Stability in Xinjiang

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photo Essay: Urban development in Korla, 2007–10

- Photo Essay: Portraits of “Old Xinjiang People,”