- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Hélio Oiticica (1937–80) was one of the most brilliant Brazilian artists of the 1960s and 1970s. He was a forerunner of participatory art, and his melding of geometric abstraction and bodily engagement has influenced contemporary artists from Cildo Meireles and Ricardo Basbaum to Gabriel Orozco, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and Olafur Eliasson. This book examines Oiticica's impressive works against the backdrop of Brazil's dramatic postwar push for modernization.

From Oiticica's late 1950s experiments with painting and color to his mid-1960s wearable Parangolés, Small traces a series of artistic procedures that foreground the activation of the spectator. Analyzing works, propositions, and a wealth of archival material, she shows how Oiticica's practice recast—in a sense "folded"—Brazil's utopian vision of progress as well as the legacy of European constructive art. Ultimately, the book argues that the effectiveness of Oiticica's participatory works stems not from a renunciation of art, but rather from their ability to produce epistemological models that reimagine the traditional boundaries between art and life.

From Oiticica's late 1950s experiments with painting and color to his mid-1960s wearable Parangolés, Small traces a series of artistic procedures that foreground the activation of the spectator. Analyzing works, propositions, and a wealth of archival material, she shows how Oiticica's practice recast—in a sense "folded"—Brazil's utopian vision of progress as well as the legacy of European constructive art. Ultimately, the book argues that the effectiveness of Oiticica's participatory works stems not from a renunciation of art, but rather from their ability to produce epistemological models that reimagine the traditional boundaries between art and life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hélio Oiticica by Irene V. Small in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Folded and the Flat

What is inside is also outside.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

This path may lie in the creation of special objects (non-objects) that occur outside all artistic convention and reaffirm art as the primary formulation of the world.

Ferreira Gullar

In Brazil in the late 1950s and early 1960s, some works of art were folded things. They displayed physical folds: pleats that drew space within them, creating inner cavities and hidden clefts, or bends that pressed flat planes into three-dimensional figures, cutting through space and organizing form against it. But their folded character was virtual as well: a free-floating notch seemingly displaced from a plane, a temporal twisting, a hinge between work and world.

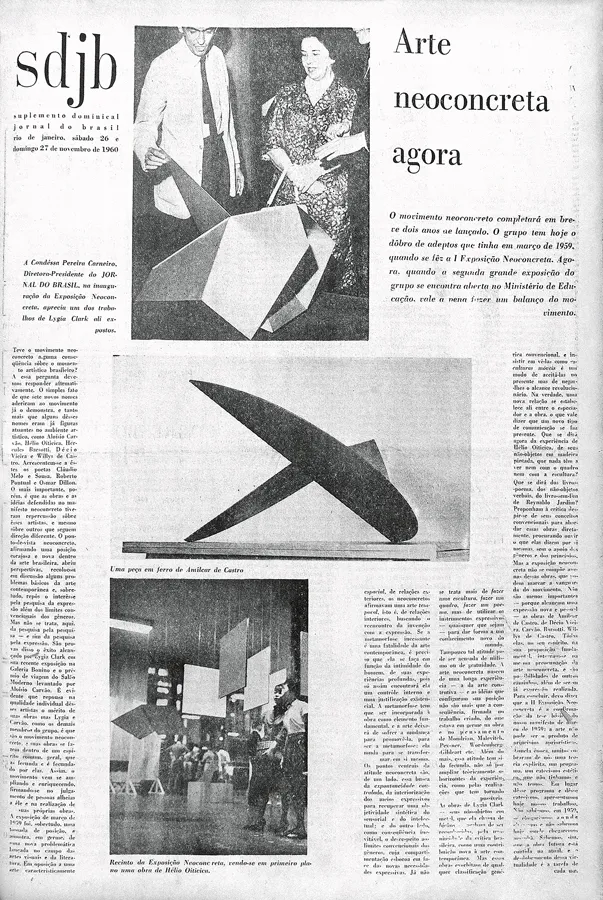

Such folded works illustrate the article “Arte Neoconcreta Agora” (Neoconcrete Art Now), published by poet and critic Ferreira Gullar in the Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil on November 27, 1960 (fig. 1.1). At top, Gullar and Countess Maurina Pereira Carneiro examine a metal sculpture by Lygia Clark, the former touching the corner of the sculpture, his hand poised as if about to turn a giant page. The hinged and folded sheets of aluminum that comprise the sculpture—its “pages”—were meant to be turned. Turned, that is, and propped, flattened, swiveled, flipped, buckled, collapsed. Clark named this sculpture and its corresponding series a Bicho (animal, critter, or beast) because each work had a life of its own. Flip one “page” and the sculpture’s entire form changes in response as its flat, polygonal shapes pivot into unexpected three-dimensional configurations. Turn it back, or attempt to, and an entirely new set of possibilities is disclosed. The Bicho’s form reveals itself successively, one “page” after another in time. Yet its heterogeneous movements defy linearity. “It is a living organism, an essentially active work,” wrote Clark. “When they ask me how many possibilities of movement [it has], I respond: ‘I don’t know, you don’t know, but it knows.’ The ‘Bichos,’” she continued, “have no reverse side.”1

Fig. 1.1 Ferreira Gullar, “Arte Neoconcreta Agora,” Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil, November 27, 1960. Courtesy of Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação do Jornal do Brasil and Ferreira Gullar.

Pictured below Clark’s sculpture is an untitled sculpture by Amílcar de Castro, likewise constructed from planes of folded metal. Unlike the Bicho, these rigid iron sheets cannot be manipulated. This work does not concern physical participation but rather the phenomenal experience of form in space: the consequences of a plane submitted to time and weight in order to fold; the apprehension of a shape that no longer has sides but, surfaces of interior and exterior extension. Space does not exist apart from form in de Castro’s sculpture. It is created, squeezed out, and enveloped by the fold. The sculpture’s generative aspect does not lie in its medium so much as in the way its materiality dynamizes and defamiliarizes spatial perception. In Gullar’s words: “It is no longer a question of making a sculpture, of making a canvas, of making a poem, but of utilizing expressive instruments—whatever they might be—in order to give form to a new understanding of the world.”2

The illustration of de Castro’s sculpture merely implies a viewer who produces such an understanding in concert with the work. But this viewer returns in the article’s last photograph of two hanging works by Hélio Oiticica made from painted wooden plaques. In the background is a Relevo Espacial (Spatial Relief) (fig. 1.23), a folded, origami-like construction composed of two interpenetrating lozenges, and in the foreground, the artist’s Bilateral Equali, an aggregate of five double-sided squares suspended so as to create rectilinear columns of air. In each work, subtle variations in painterly tone—red and orange in the first instance, white-on-white in the second—render surface and edge as a series of chromatic zones. This spatialized modulation of color compels viewers to circumambulate the work and occupy its spatial intervals. Integrating plane and periphery through the cessation or continuity of a given tone, viewers perceptually create and recreate the work’s folds, activating its structure in kind.

As the photograph makes clear, Oiticica’s hanging works have little use for frames. Frames enclose works of art from space, so designating their self-sufficiency. The folded forms and operations of these works depend upon space. In so doing, they enter into a dialogue, not simply with space but with everything space contains: the unordered world of real bodies, the chaotic realm of ordinary things. This, too, is visible in the picture. In seeking to capture the works’ scale, their phenomenological solicitation of the viewer, and finally their peculiar status as neither painting nor sculpture but suspended spatial structure, the photographer has documented a host of contingencies: the gloss of the suspending wires, the wooden scaffolding of a poster board, the puckering of a viewer’s shirt, the glint of an overhead light. Incidental to the work, such details are nevertheless pulled into its orbit in the process of encounter and documentation. The folds that turn these works back upon themselves, generating their reflexivity as autonomous aesthetic entities, then, are also the folds that dispel the distinctions between a given work’s interior and exterior space. Here, self-same operations consistently give rise to difference rather than equivalency.

The occasion for these photographs was the 2° Exposição de Arte Neoconcreta (2nd Exhibition of Neoconcrete Art), which opened in Rio de Janeiro on November 21, 1960. At this exhibition, the budding movement of Neoconcretism demonstrated its vigor, having added several members to its ranks—Oiticica among them.3 Gullar emphasized that the Neonconcretists did not “constitute a ‘group’” and that their works exceeded “any conventional classification of genre.”4 Rather, their coherence stemmed from a shared investment in the work of art’s capacity to activate spectators through emergent rather than predetermined perceptual phenomena. For Gullar, this established nothing short of a “new type of communication.”5

What might such a “new type of communication” have meant in Brazil circa 1960? A type of communication reported in a newspaper, itself a vehicle for communication, and announced by a writer—Gullar—pictured within his article as an ideal viewer and thus coproducer of the Neoconcrete work? Between 1956 and 1961, Brazil’s most advanced modern art and poetry were divulged, theorized, and debated in the pages of the Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil, the Sunday supplement of the Rio-based daily Jornal do Brasil. Gullar was an art critic for the supplement and principal theorist of the Neoconcrete movement. The countess was director and president of the Jornal do Brasil, and it was her initiative that had brought the Suplemento Dominical into being in 1956. The photograph of the two with Clark’s Bicho at the top of the article “Arte Neoconcreta Agora” thus sets forth a complex chain of associations between readers and writers, artworks and pages, patrons and spectators, observers and users. Such a relay situates the embodied encounter described within the bounds of the article vis-à-vis the embodied encounter that occurs beyond it—in the space of information transfer typified by the newspaper itself.

This space, too, is conditioned by folds. Folds that collapse a newspaper’s textual density into an object, that are reversed when its pages are extended on a plane, that are reiterated and reconfigured by readers in the process of navigating the newspaper’s content. Indeed, it would be tempting to suggest that these dual instances of folding—the folded artwork and the folded pages of the newspaper—are isomorphic in character. Such a one-to-one correspondence would posit the work of art as a self-contained model for a social practice writ large. Yet the newspaper and the Neoconcrete work approach communication and a host of attendant terms—information, fact, message, knowledge—through radically different means. While the prototypical form of the newspaper is folded, for example, its informational content is legible only when it establishes a readerly zone that is flat. This zone may consist of a full two-page spread or a single column isolated by a reader by means of multiple folds. In either case, folding is a means of delivering flatness. But it is flatness that is the newspaper’s privileged communicative state.

By contrast, the Neoconcrete work conveys no content save the spatial and chromatic relations produced in the process of its perception. It does not transmit preexisting information as much as it provides the conditions for informational construction within a situated time and space. Like the newspaper, it becomes a communicative entity by virtue of its folds. But we might say that it mobilizes the newspaper’s medium rather than its message, isolating that interval in which content is suspended in favor of the independent materiality of the page. Refusing to reference or illustrate the world, the Neoconcrete work nevertheless establishes a coterminous relationship with it in time and space. The “new type of communication” lauded by Gullar is therefore one positioned in contradistinction to that of the newspaper, but plied from the very caesuras by which a newspaper’s communication takes shape.

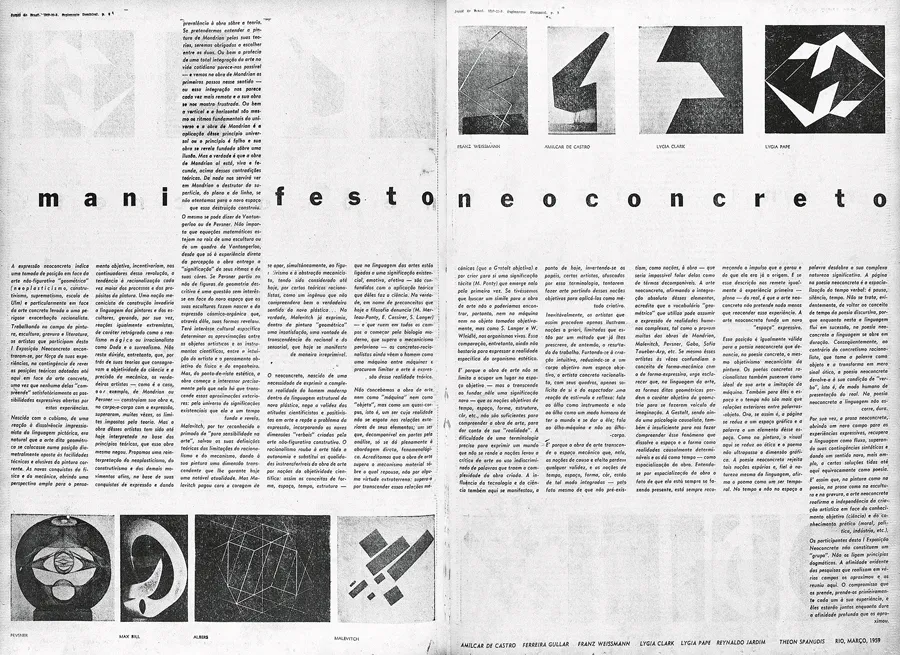

This chapter charts the emergence of two communicative modes—“the folded” and “the flat”—that were operative within works and discourses of Brazilian geometric abstraction between 1956 and 1961 and that shape the aesthetic field through which Oiticica conceived of his first mature works. This period coincides with the split of the Concrete artists and poets of Rio from those of São Paulo following the 1° Exposição Nacional de Arte Concreta (1st National Exhibition of Concrete Art), which opened in São Paulo in December 1956 and traveled to Rio in February 1957. It also coincides with the complete run of the Suplemento Dominical, which published key polemics leading to the rupture and served as the discursive vehicle for the new movement of Neoconcretism to establish its theoretical claims (fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil, March 22, 1959. Courtesy of Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação do Jornal do Brasil.

The break between the two groups has long been narrated as a difference in sensibility: between Concrete rationality and Neoconcrete intuition. First advanced in contemporaneous polemics but repeated ad infinitum in later accounts, this explanation appeals to long-standing, if highly clichéd, tensions between residents of the two cities.6 In its sheer simplicity, it has consolidated putatively coherent historical movements while ignoring the fluidity of identification and divergence. While this regionalist narrative is insufficient as a causal explanation for the distinctions between Concretism and Neoconcretism, we must nevertheless take seriously the imperative to become distinct to comprehend the historical import of the works in question.7 As Brazilian critic Ronaldo Brito argued in his pioneering 1975 analysis, Neoconcretism staked its significance on a negation or supersession of Concretism in largely art historical terms.8 Yet in so doing, Neoconcretism crystallized the limits of the claim to universality upheld by Concrete movements in Brazil and elsewhere. By refusing to acknowledge either rupture or contradiction (for them, the Neoconcretists were simply “disoriented” Concretists), the Concretists held on to this universalist fiction, even as it butted up against the local specificities of Brazil.

Such misalignments between universality and place are not surprising, as Concretism was itself something of a phantasm in the postwar period. Although its name derives from an eponymous 1930 manifesto by Theo van Doesburg that outlines a rigorously anti-representational, anti-naturalistic basis for painting, its implications in Brazil were tightly bound to articulations popularized by Swiss artist Max Bill and Argentine artist, theorist, and designer Tomás Maldonado in the 1940s and 1950s.9 Trained at the Bauhaus in the late 1920s, Bill was associated with avant-garde figures such as Piet Mondrian and Jean Arp in the 1930s. In the postwar period, he fashioned himself as the principal disseminator of Concrete art in the international sphere. Through publications, exhibitions, and at the Hochschule für Gestaltung—an institute of design he cofounded in 1953 in Ulm, Germany—Bill promoted a systematic, mathematical art that, lacking the radicalism of earlier avant-gardes, was nevertheless utopian and universalizing in its aspirations. In 1950, the newly inaugurated Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) staged a retrospective of Bill’s work. The following year, his sculpture Tripartite Unity won the international prize at the 1st São Paulo Bienal.10 In 1953 he returned to Brazi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Note on the Text

- Introduction

- 1 The Folded and the Flat

- 2 The Cell and the Plan

- 3 Ready-Constructible Color

- 4 What a Body Can Do

- Coda

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index