eBook - ePub

Performing Afro-Cuba

Image, Voice, Spectacle in the Making of Race and History

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Visitors to Cuba will notice that Afro-Cuban figures and references are everywhere: in popular music and folklore shows, paintings and dolls of Santería saints in airport shops, and even restaurants with plantation themes. In Performing Afro-Cuba, Kristina Wirtz examines how the animation of Cuba's colonial past and African heritage through such figures and performances not only reflects but also shapes the Cuban experience of Blackness. She also investigates how this process operates at different spatial and temporal scales—from the immediate present to the imagined past, from the barrio to the socialist state.

Wirtz analyzes a variety of performances and the ways they construct Cuban racial and historical imaginations. She offers a sophisticated view of performance as enacting diverse revolutionary ideals, religious notions, and racial identity politics, and she outlines how these concepts play out in the ongoing institutionalization of folklore as an official, even state-sponsored, category. Employing Bakhtin's concept of "chronotopes"—the semiotic construction of space-time—she examines the roles of voice, temporality, embodiment, imagery, and memory in the racializing process. The result is a deftly balanced study that marries racial studies, performance studies, anthropology, and semiotics to explore the nature of race as a cultural sign, one that is always in process, always shifting.

Wirtz analyzes a variety of performances and the ways they construct Cuban racial and historical imaginations. She offers a sophisticated view of performance as enacting diverse revolutionary ideals, religious notions, and racial identity politics, and she outlines how these concepts play out in the ongoing institutionalization of folklore as an official, even state-sponsored, category. Employing Bakhtin's concept of "chronotopes"—the semiotic construction of space-time—she examines the roles of voice, temporality, embodiment, imagery, and memory in the racializing process. The result is a deftly balanced study that marries racial studies, performance studies, anthropology, and semiotics to explore the nature of race as a cultural sign, one that is always in process, always shifting.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Performing Afro-Cuba by Kristina Wirtz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226119052, 9780226118864eBook ISBN

97802261191991

Semiotics of Race and History

Señores, hasta aquí llegamos, al compás de este vaivén

Saludando al territorio, y pa’ la Isuama también

Gentle audience, we have arrived as far as here, in time with this journey

Greeting the territory, and the Isuama [society] as well

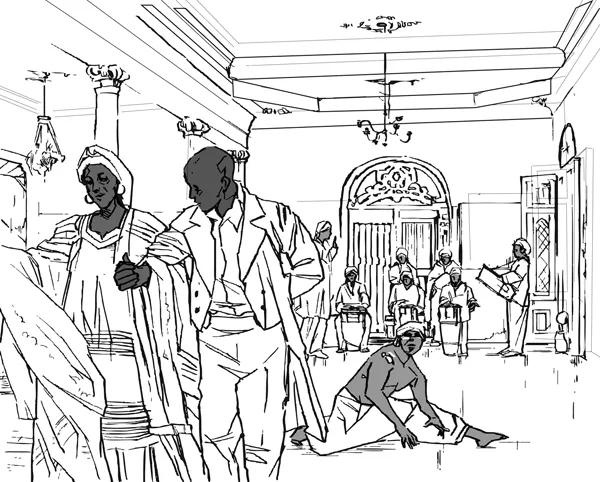

A memory: Two dancers sweep onto the floor before the audience as the song begins. They are elegantly dressed, Sergio in a grey suit with tails and Maura daintily holding up the skirt of her ruffled, floor-length white dress, and their postures are regal, even haughty (fig. 1.1). They are royalty, stepping high to the drums.

Que la reina del cabildo, ja, ja, ja, es la que se va coronada

That the queen of the cabildo, ha ha ha, is the one who bears the crown

So sings the lead singer, Manolo Rafael Cisnero Lescay, in his operatic baritone, backed by three other singers as the chorus, repeating his lines. A sly, crouching figure watches: a male dancer clad only in loose white britches gathered just below the knee, head wrapped in a red kerchief. Wielding his machete, he follows the pair with awe, then beckons to five companions, who join him in pantomiming their fascination with the elegant pair and their dance. The elegant couple exits and the men repeat their steps, intermingled with dances of carrying loads and cutting sugarcane: the labor of slaves. The song’s lyrics now repeat a new refrain between lead and chorus:

Eso es verdad, eso es así, Olugo me trajo a Cuba a bailar carabalí

That’s the truth, that’s how it is, Olugo brought me to Cuba to dance carabalí

Suddenly, a striking figure appears, moving with fierce energy: Chirri is dressed in loose britches like the other “congos,” his bare chest is crisscrossed with white strips of cloth and a long pendant, and his cheeks are hatched with painted African “country mark” scars, bright white on his dark skin. As he dances around the others, intimidating them, he puffs at a cigar stub and rolls his widened eyes, his face frozen in a fixed stare (see fig. 1.2). He conjures the brujo, witch; he throws the others into paroxysms of possession trance on the floor. He works his dark magic, pulling snakes from a tall, carved wooden vessel that evokes both drum and witch’s cauldron, then duels with a challenger, and after that stalks the very edge of the audience with two thin torches, burning each along the length of his arm. In a nifty theatrical trick, he blows streams of fire from his mouth then extinguishes the flaming wands in his mouth.

FIGURE 1.1 Sergio Hechavarría Gallardo and Maura Isaac Álvarez perform a Carabalí dance as another dancer in the role of a “Congo” watches, in Trilogía africana, by Ballet Folklórico Cutumba, Santiago de Cuba, July 2006. Line drawing by Jessica Krcmarik of still image from author’s video recording, used with permission.

I have seen Santiago de Cuba’s Ballet Folklórico Cutumba rehearse and perform this piece, Trilogia africana, several times over the years, but my memory always fixes on this one performance in 2006, in the colonial ambience of the Casa de Estudiantes, just off the old central Parque de Céspedes plaza in Santiago de Cuba, eastern Cuba.1 The Casa de Estudiantes, which closed soon thereafter for renovation, is a classically Spanish colonial two-story mansion, built as a square around an open-air central courtyard, with its expanse of tile floors, and graceful, arched columns, the folding chairs set out facing an area for performance and with the Cutumba musical ensemble—percussionists and singers—lining the opposite wall. All around was Caribbean yellow with white trim—decrepit, crumbling, and therefore much more evocative of times past. A large Cuban audience surrounded a group of visiting European dance aficionados perched on metal folding chairs, everyone responding with excitement, gasps, even shouts and squeals, as the performance progressed.

FIGURE 1.2 Robert (Chirri) Nordé LaVallé dances the role of the brujo, “witch,” in Trilogía africana, by Ballet Folklórico Cutumba, Santiago de Cuba, July 2006. Line drawing by Jessica Krcmarik of still image from author’s video recording, used with permission.

This is my memory, aided by my video recording of the event. The performance itself is a remembrance, a re-creation of some imagined past of Afro-Cuba set amid the colonial architecture. All of its elements of music, dance, choreographed narrative, instruments, costumes, makeup, and even the dancers’ brown-hued skin convey a sense of what the traditions and legacies of African-descended Cubans are and, thus, of what Cuba’s African heritage means today. In this book, I examine how performing particular stories about the past, on stages, in streets, and during rituals, shapes processes of racialization in the present. William Faulkner’s aphorism echoes for me in Cutumba’s performance: “The past is never dead. It is not even past” (from Requiem for a Nun [1951]). The past moves in and through the present, like a ghost, or a memory, or a sense of tradition, and it does so because living people selectively animate particular pasts, choosing what will be remembered as history, what kinds of things will serve as signs of that history, what will be forgotten, and what relationship those signs defined as “past” will have with the present moment. While some tellings of the past gain a hegemonic hold on particular locations of the present, histories are heterogeneously conceived, being active creations in and of each moment of the present. The prevalence of performances like the “African Trilogy” tells us that some remembrance of Cuba’s colonial past as a slave society has significance for Cubans today. I take this observation as the opening for investigating: What significance? For whom? And why?

Consider the ongoing relevance of the transatlantic slave trade and slave societies in the Americas: What does this history, shared throughout the Western hemisphere and the wider Atlantic World, mean to us in this present moment of the early twenty-first century? The persistent racial hierarchies evident in African Diaspora societies throughout the Americas are proof enough of slavery’s legacy. But in many American societies, not least among much of the U.S. population, the times of slavery feel very distant. In some societies—Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, Argentina—the past of African slavery has faded almost into oblivion. To others—many Cubans, Surinamese Saramaka, African Americans—the era of slavery feels quite recent still.2 Why these differences? What stake do we have in situating slavery in the distant versus the near past, in citing or denying its contemporary relevance?

In a groundbreaking critique of “verificationist” approaches to studying historical consciousness in and of the African Diaspora, David Scott (1991, 278) argues for replacing concerns about authenticating the historical narratives of subaltern groups with questions about how such narratives construct “relations among pasts, presents, and futures” and with what consequences. Notable among responses to this call, Edmund Gordon and Mark Anderson (1999) and Paul Johnson (2007) have examined shifting “horizons” of historical consciousness among Garifuna and Nicaraguan Creole communities that destabilize anthropological assumptions that who “belongs” to the African Diaspora (or doesn’t) is necessarily obvious. As Gordon and Anderson (1999) suggest, ethnographies of diaspora identification are needed. I would extend this call to understand the historical consciousness of subaltern groups not only in themselves but also in relation to other often powerful forms of historical and racial consciousness that may construct Blackness (alongside other racialized categories) and thus membership in the African Diaspora (or its impossibility) as self-evident categories.

Too often, the very concept of race, and particularly of Blackness, gets divorced from its history of conquest, slavery, and normalized inequality to be set on a timeless, eternal plane as an inescapable biological reality, written in phenotype and genealogy. Such naturalized notions of Blackness, in turn, are linked to longstanding imaginings of Africa as a continent unified into a homogenous, culturally and racially deterministic region like no other (Mudimbe 1994). At the broadest level, a contribution of this book is to demonstrate anew that concepts of race do have a history, that racial logics, including ideologies of racial embodiment, require continued cultural effort to be sustained, and that the historical imagination is inextricably entangled with the racial imagination. Blackness is neither a straightforward natural category nor a straightforward historical category. It is, rather, a complex series of cultural constructions whose various, overlapping histories encompass several continents and oceans over half a millenium.

Cuba is but one site where Blackness is a salient category, and it is the site I focus on in this book. Cubans recognize Blackness both as a matter of African descent that, because of miscegenation, may or may not quite always align with racialized phenotypic markers, and as a cultural inheritance from Africa and African descendants in Cuba. Tremendous complexities result from this dual realization of Blackness as genealogical and cultural heritage—complexities only hinted at by formulations such as Fidel Castro’s (1975) claim that Cuba is not only Latin American but “a Latin-African nation” because “the blood of Africa runs abundantly in our veins.” On the occasion of Castro’s speech, claims of Blackness “in the blood” were a rhetorical strategy situating racial discrimination in Cuba’s prerevolutionary past and antifascist, anti-imperialist “internationalist” struggle in its present and future. The ways in which Blackness is temporalized are evident in folkloric as well as political performances, where the latter in fact often implicitly point to the former.3 I suggest that studying links between folklore performances of Blackness and Cuban national historical consciousness can tell us something more general about how racialization works everywhere.

One strand of my argument will be to trace out the performative effects of folklore performance, and here I must pause to explain my terminology. The distinction between performance and the performative that I follow in this book is not a new one, but I find the interface between the two to be productive. Quite a lot of the data I present concern performances, meaning events framed as virtuosic displays, in the sense developed by Dell Hymes and Richard Bauman, among others (Bauman 1993, 2011; Bauman and Briggs 1990; Hymes 1972). This is because so much of folklore performance in contemporary Cuba has focused on figurations of Blackness. But to speak of racialization processes, as I do, is to also invoke the performative, in the sense proposed by natural language philosopher John Austin and developed by more recent social theorists such as Judith Butler, and meaning the capacity of social actors to constitute their worlds. The most simple case is Austin’s speech acts—paradigmatically, constructions such as “I promise,” “I command”—but notice that the performative effects of such utterances depend, among other things, on social norms arising out of histories of use that presuppose what such constructions “do” in the world. Clearly, the performative function of language exceeds the limited case of verb constructions that explicitly state their intended effect (Silverstein 2001). In the work of Butler and others, the notion of the performative has been developed to explain how seemingly durable but sociohistorically specific constructs—gender, race, class—are given social force through their ongoing reiterations that create subjects as well as the (gendered, raced, classed, etc.) subject positions we occupy. The performative need not co-occur with specially framed performances, in the first sense above, since the performative permeates everyday interaction and larger-scale discursive processes alike. But I am particularly interested in the performative effects of folklore performances in mobilizing figurations of Blackness that do indeed have wide impact, or so I argue, on how Blackness matters in the Cuban historical imagination and as a contemporary subject position.

The particular story that unfolds in this book—of race and history, of folk religiosity and folklore performance, of pride and prejudice—began for me in mingled bedazzlement and puzzlement. From my first days in the eastern Cuban city of Santiago de Cuba in early 1998, my attention was drawn to folkloric and religious dances that enacted, I was told, traditions of enslaved Africans and their Afro-Cuban descendants. Performers and audiences, mostly self-identifying as Afro-Cuban in this most “Caribbean” of Cuban cities, expressed pride in these traditions. Not only professional performers of folklore but also amateur enthusiasts, musicians and dancers in carnival comparsas (Cuban carnival ensembles), and practitioners of Cuba’s host of folk religions partook in reanimating African and slave figures from Cuba’s past.

Sometimes, these performances brought me face to face with the kind of caricatured depictions of “primitive” and “wild” Africans, like the brujo (witch) and his corps of dancing slaves, that uneasily reminded me of North American traditions of blackface minstrelsy and Wild West shows featuring “primitive” Indians. To complicate matters, many of the performance tropes of folklore shows—bulging eyes, fixed stares, grimaces and inarticulate cries, fierce displays with machetes, speech keyed as “African”—were also evident in semiprivate religious ceremonies, when saints and spirits possessed people to mingle among the living and dispense advice. These riveting and unsettling performances demanded my attention, and in 2006 I began to study these stereotyped and instantly recognizable figures of Africans, slaves, maroons (escaped slaves), and Black witches. Such characterizations are staples of folkloric dance choreographies by amateur clubs and professional ensembles alike, in which they may interact with each other in dramatic tableaus that Cubans have long called “theaters of relations.” They appear not only as physical types, marked by distinctive costumes, props, speech styles, choreographies, and behaviors—and significantly, darker skin color of the performers—but also as discursive figures and voices in songs from a wide array of religious, folkloric, and popular music genres. In raising the ghosts of Cuba’s colonial slave society, these performances raise questions about how the past is imagined and what role these images of the past have in the present.

It will be apparent that the story goes back much further than my relatively recent ethnographic encounter with Cuba at the end of the 1990s. Racializing performances of Blackness have a history as long as the history of African presence in Cuba and indeed its colonizer, the Iberian Peninsula. In the age of Cervantes, Spanish writers were producing comic dialogues and sacred song lyrics representing a distinctive, parodied “African” voice, one that became the sound of bozal, or “wild,” African-born slaves. This imagination of a new category of sub-Saharan Africans, in turn, drew on an older history of Christian-Moor-Jew-Gypsy relations in southwestern Europe, one whose traces remain evident.4 And, in turn, the legacy of early age-of-exploration Iberian genres such as the negrillo is evident throughout colonial Latin America as well, from Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz’s literary production in late seventeenth-century New Spain (now Mexico) to Cuba’s mid-nineteenth-century teatro bufo and the twentieth-century blackface performances that followed. There is also a somewhat more obscure lineage of African critiques and counterparodies, less visible in the written historical record and more evident in performance traditions of religious cofraternities and societies of mutual aid and latter-day folklore societies and carnival ensembles. More apparent yet are twentieth- and twenty-first-century spaces of Afro-Cuban self-definition, pride, and autonomy, including these same folklore and carnival societies but also religious practices, grassroots carnival traditions, and other family- and neighborhood-centered interactional spaces.

To add to the complexity, the Cuban revolutionary state has, since taking power in 1959, prioritized the cultural forms identified with the lower classes—peasants and proletariat—that comprise what the Cuban Ministry of Culture characterizes as the “folk” and “popular” realms of culture. Such official attention, oscillating between surveillance, celebration, preservation, appropriation, and control, has been a mixed blessing. With it has come state support for what it designates to be “carriers of tradition,” “aficionado” groups, and professional ensembles serving as “interpreters of tradition” for local, national, and international audiences (the terms in quotes are official categories). Cultural forms identified as African or Black have, in the course of these processes of folklorization, become almost synonymous with “the folkloric” in Cuba (Duany 1988), an identification that began even before the sea change of the 1959 revolution. These forms encompass kinds of ritual practice, sociality, music, and dance. Perhaps most prominent are popular religious practices, such as Santería and the Reglas de Palo. Diverse kinds of associations are keyed as Black, even though participation has long been racially inclusive: in western Cuba there are Abakuá men’s secret societies and wide-open rumba jams; where I do research in eastern Cuba, traditional folklore societies organized by neighborhood are prominent, including the Carabalí cabildos and the “congas” or carnival comparsas. And emanating from these and other sites marked for their “Black” authenticity are many genres of “Afro-Cuban” folkloric music and dance, now well-cataloged in the repertoires of state-sponsored folklore ensembles. As such, these forms and the social groups they mark have become essential to the work of historical imagination by the state and by its citizens, at various ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Agradecimientos

- List of Illustrations

- 1. Semiotics of Race and History

- 2. Image-inations of Blackness

- 3. Bodies in Motion: Routes of Blackness in the Carnivalesque

- 4. Voices: Chronotopic Registers and Historical Imagination in Cuban Folk Religious Rituals

- 5. Pride: Singing Black History in the Carabalí Cabildos

- 6. Performance: State-Sponsored Folklore Spectacles of Blackness as History

- 7. Brutology: The Enregisterment of Bozal, from “Blackface” Theater to Spirit Possession

- Notes

- References Cited

- Index