eBook - ePub

The Voice as Something More

Essays toward Materiality

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Voice as Something More

Essays toward Materiality

About this book

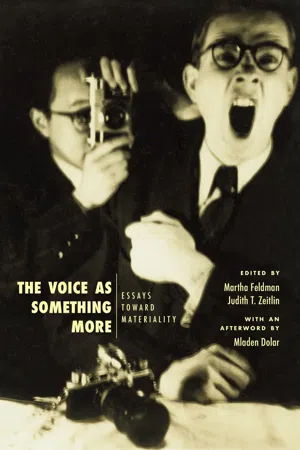

In the contemporary world, voices are caught up in fundamentally different realms of discourse, practice, and culture: between sounding and nonsounding, material and nonmaterial, literal and metaphorical. In The Voice as Something More, Martha Feldman and Judith T. Zeitlin tackle these paradoxes with a bold and rigorous collection of essays that look at voice as both object of desire and material object.

Using Mladen Dolar's influential A Voice and Nothing More as a reference point, The Voice as Something More reorients Dolar's psychoanalytic analysis around the material dimensions of voices—their physicality and timbre, the fleshiness of their mechanisms, the veils that hide them, and the devices that enhance and distort them. Throughout, the essays put the body back in voice. Ending with a new essay by Dolar that offers reflections on these vocal aesthetics and paradoxes, this authoritative, multidisciplinary collection, ranging from Europe and the Americas to East Asia, from classics and music to film and literature, will serve as an essential entry point for scholars and students who are thinking toward materiality.

Using Mladen Dolar's influential A Voice and Nothing More as a reference point, The Voice as Something More reorients Dolar's psychoanalytic analysis around the material dimensions of voices—their physicality and timbre, the fleshiness of their mechanisms, the veils that hide them, and the devices that enhance and distort them. Throughout, the essays put the body back in voice. Ending with a new essay by Dolar that offers reflections on these vocal aesthetics and paradoxes, this authoritative, multidisciplinary collection, ranging from Europe and the Americas to East Asia, from classics and music to film and literature, will serve as an essential entry point for scholars and students who are thinking toward materiality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Voice as Something More by Martha Feldman, Judith T. Zeitlin, Martha Feldman,Judith T. Zeitlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Musik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Sound-Producing Voice

1

Speech and/in Song

STEVEN RINGS

In our daily world of social interactions, singing is marked, speech unmarked; in the world of song, the reverse holds.1 Such, at least, is the commonsense view, which might tempt us to assume a difference in kind between speech and song. Yet scholars from fields as diverse as anthropology, linguistics, and cognitive science have long argued that the difference is instead one of degree—speech and singing arrayed on a continuum. Aaron Fox, for example, lends an attentive ear to the musicality of everyday speech in white, rural Texas, and explores its affiliations with country singing.2 Fox’s work intervenes in a long ethnomusicological tradition of probing the porous border between speech and song.3 An intellectual world away, perceptual psychologist Diana Deutsch has demonstrated the ways in which repeated snippets of speech can quickly begin to sound like singing.4 She stumbled on the phenomenon heard in website example 1.1 which involves her own voice—by accident, while editing a recording. As one listens, the change is both gradual and immediate, a difference in degree that eventually throws off its cloak to reveal a difference in kind. Deutsch’s voice seems to cross a qualitative threshold at some point, taking on a kind of material insistence. Removed from the syntagmatic chain of speech, the musical aspects of her voice—pitch, rhythm, timbre—are somehow vivified, brought to life and dancing before our ears. The words’ propositional force, by contrast, falls away, leaving behind a phonemic husk. Sounds behaving strangely, indeed.

Though Deutsch artificially manufactures her example through a looped recording, real-world examples in which repetitive, heightened speech approaches the condition of song are not hard to find: the auctioneer, the keening mother, the charismatic preacher, the Quranic reciter. In such examples, musicality and communicative context are inseparable. But a small technological nudge can disturb the balance. Consider website example 1.2, the opening of Steve Reich’s 1965 tape piece It’s Gonna Rain.5 Reich manipulates a recording of Pentecostal preacher Brother Walter delivering an apocalyptic sermon in San Francisco’s Union Square in 1964. Walter’s speech approaches the condition of song all on its own, an effect that Reich heightens through unnervingly tight loops.

In these examples, we hear song emerging from within speech, so to speak, as a kind of latent presence or potential. And when it emerges, the voice can seem to reclaim its material autonomy, phoné asserting itself over and against logos.6 Per Aaron Fox, this material assertion is an effect of singing in general: “Singing heightens the aural and visceral presence of the vocalizing body in language, calling attention to the physical medium of the voice, the normally taken-for-granted channel of ‘ordinary’ speech.”7 But what about those contexts when “ordinary speech” is not the norm, but singing is? That is, what about speech in the world of song? If quotidian speech makes the materiality of the singing voice perspicuous, does song repay the debt? That is, in the world of song, does speech become audible?

I pose these questions not to suggest that they admit of univocal answers—there are too many traditions of speaking within song for that—but to prime our ears for the gallery of examples that I will explore in this chapter. They are drawn from diverse popular song traditions—early country to recent hip-hop—and each involves a performer who both speaks and sings. This leaves out a lot, most notably art music traditions like Sprechstimme, melodrama, Singspiel, opéra bouffe, and so on, as well as musical theater. Moreover, I will not consider popular music examples in which an individual speaks who is not the singer (think Vincent Price in Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”). There will nevertheless be plenty to discuss. I am especially interested in the ways in which speech can emerge as a marked figure against the unmarked ground of more conventionally coded musical sound, a relationship that can focus our ears on the very sonic features that often fade into transparency (or inaudibility) in everyday talk, as Fox notes. Here, though, Fox’s relationship is reversed, as it is speech that can seem to regain its granular opacity within song. We will also attend to the ways in which the speech-song dynamic can interact with questions of meaning, sometimes animating lyrics with a kind of heightened hermeneutic legibility, at others suggesting a dialectic of interiority and exteriority, at still others, modeling diverse modes of real-world social or performative interaction. Finally, I will explore the ways in which these performers vocally navigate the transition from song to speech or vice versa. In some examples, vocalists explicitly cordon speech off from song—the commonsense notion of a difference in kind retaining its force—while in others, performers fluidly traverse a continuum between speech and song. Strikingly, through the 1980s, vocalists of the latter type—whom we might call “continuum singers”—tend to come from largely white, northern, urban scenes lionized by a critical elite (think folk revival, punk, indie). By contrast, the more sharply demarcated examples reside on the margins of elite taste (think early country and R&B). Along the way I will venture some thoughts on this rather Bourdieuian state of affairs,8 and also note its dissolution in the hip-hop era, which has led to an extraordinary flourishing of vocal practices, speech and song circulating ever more freely.

Hank Williams, “Pictures from Life’s Other Side” (1951)

There is an entire genre of country song called the “recitation song,” in which the singer either speaks throughout or alternates speaking and singing. The subject matter is often devotional or cautionary, with nods to tent revival and radio preaching traditions. As Hank Williams biographers Colin Escott, George Meritt, and William MacEwen put it, “The recitation was a little homily, usually with a strong moral undertone, narrated to musical accompaniment.”9 Recorded examples date back to the 1930s; by the 1950s, recitation songs were an old-fashioned, niche item. Hank Williams nevertheless maintained a deep fondness for the genre, despite his producer Fred Rose’s resistance, and recorded some of its most celebrated examples in the final years of his life, under the name Luke the Drifter.10 Among the most famous is “Pictures from Life’s Other Side,” which Williams recorded in 1951, and which became the first track on the posthumous LP Hank Williams as Luke the Drifter. The song consists of three spoken verses and one sung chorus. The verses narrate tragic scenes “from life’s other side,” while the chorus offers a capsule meditation in song. Website example 1.3 includes the first verse and the beginning of the chorus.

The crisp distinction between vocal modalities is immediately evident. As in all of his Luke the Drifter recitations, Williams shuttles between two discrete registers: he either speaks or he sings, but he does not shade gradually from one to the other. Yet it is worth noting that the spoken portions are not everyday speech—they are heightened. Williams’s intonation suggests the fervor and intensity of a radio preacher, while the prosody and rhyme scheme match the sung chorus rather than the rhythms of colloquial speech. Indeed, at times his reciting voice feels almost yoked to the musical structure, pulled ineluctably forward. This is one reason for the sense of urgency and peril that belies the folksy drawl. Another is Williams’s tendency to draw out certain syllables with quivering intensity, as on the words “pictures” (pronounced “pitchers”) and “love” in the third line of verse one (“There’s pictures of love and of passion”). Why, then, do the verses register so unambiguously as speech? Most obvious is Williams’s treatment of pitch and contour. He explicitly—and perhaps exaggeratedly—shapes each syllable with the characteristic arch of speech, sliding into and out of emphasized syllables, rather than settling on sustained pitches slotted into the discrete locations of the diatonic scale (in this case, E major).

This avoidance of sung pitch means that Williams’s voice can no longer project that central element of popular song: the melody. But the melody is there, nestled into the musical accompaniment behind Williams’s recitation. Note the fiddle in website example 1.3 (played by Jerry Rivers). This is a phenomenon common to recitation songs, and indeed to songs in many genres that involve speaking: the melodic line, as though extracted from the voice, is relocated to a different part of the sonic texture. I will refer to this as melodic “ghosting.” Williams’s speaking voice is ghosted throughout the song: by Rivers’s fiddle in verses one and three, by Don Helms’s steel guitar in verse two. Tellingly, the ghosted melody disappears in the chorus, when Williams sings. Yet the logic of ghosting is not subtractive in any simple sense: the voice is not made less by the process. Rather, it can seem to gain a kind of palpable materiality, as the complex grain of speech emerges into sonic relief against the conventional code of the melody and its embedding country waltz. By making sonically explicit that parameter of the musical texture that the voice no longer possesses—melody—the ghosted line paradoxically amplifies the speaking voice. Ghosted melody settles unobtrusively into the accompanimental fabric, reinvesting the speaking voice with obdurate, material difference.

In country recitation songs, this crisp division between recitation and coded song indexes a shift in implied participatory musicking.11 In the verses, Williams addresses the listener in narration; in the chorus, he solicits participation.12 Singing, after all, affords “singing along.”13 Indeed, the musical code underwrites the social efficacy of group singing, allowing participants to anticipate pitch and rhythm, affording entrainment with the overall flow of the music (however inexact that entrainment might be in practice).14 Everyday speech affords no such opportunities for entrainment or pitch matching. Though one perhaps could “speak along” to Williams’s recitation in “Pictures from Life’s Other Side,” given its regular prosody, to do so would seem odd. The narrative explicitly suggests a direct address. Indeed, Williams enacts this address even more explicitly on other Luke the Drifter songs, beginning with locutions that evoke radio preaching, such as “You know, friends . . .” (“Help Me Understand”) or “Now, friends . . .” (“I’ve Been down That Road Before”). When the sung chorus or refrain arrives, one can then easily imagine an audience that had been listening attentively to the verse joining in for the chorus, much as a congregation sings a hymn after a sermon.

The interaction of speech and song in country recitations often invites hermeneutic attention. Consider website example 1.4, the final verse from “Pictures from Life’s Other Side.” Williams recites the opening of the verse as before, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Illustrations

- List of Musical Examples (Print)

- List of Website Examples (Audiovisual)

- introduction

- The Clamor of Voices

- part i Sound-Producing Voice

- part ii Limit Cases

- part iii Vocal Owners and Borrowed Voices

- part iv Myth, Wound, and Gap

- part v Interlude: The Gendered Voice

- part vi Technology, Difference, and the Uncanny

- List of Contributors

- Index