- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This classic study of how 282 men in the United States found their jobs not only proves "it's not what you know but who you know," but also demonstrates how social activity influences labor markets. Examining the link between job contacts and social structure, Granovetter recognizes networking as the crucial link between economists studies of labor mobility and more focused studies of an individual's motivation to find work.

This second edition is updated with a new Afterword and includes Granovetter's influential article "Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problems of Embeddedness."

"Who would imagine that a book with such a prosaic title as 'getting a job' could pose such provocative questions about social structure and even social policy? In a remarkably ingenious and deceptively simple analysis of data gathered from a carefully designed sample of professional, technical, and managerial employees . . . Granovetter manages to raise a number of critical issues for the economic theory of labor markets as well as for theories of social structure by exploiting the emerging 'social network' perspective."—Edward O. Laumann, American Journal of Sociology

"This short volume has much to offer readers of many disciplines. . . . Granovetter demonstrates ingenuity in his design and collection of data."—Jacob Siegel, Monthly Labor Review

"A fascinating exploration, for Granovetter's principal interest lies in utilizing sociological theory and method to ascertain the nature of the linkages through which labor market information is transmitted by 'friends and relatives.'"—Herbert Parnes, Industrial and Labor Relations Review

This second edition is updated with a new Afterword and includes Granovetter's influential article "Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problems of Embeddedness."

"Who would imagine that a book with such a prosaic title as 'getting a job' could pose such provocative questions about social structure and even social policy? In a remarkably ingenious and deceptively simple analysis of data gathered from a carefully designed sample of professional, technical, and managerial employees . . . Granovetter manages to raise a number of critical issues for the economic theory of labor markets as well as for theories of social structure by exploiting the emerging 'social network' perspective."—Edward O. Laumann, American Journal of Sociology

"This short volume has much to offer readers of many disciplines. . . . Granovetter demonstrates ingenuity in his design and collection of data."—Jacob Siegel, Monthly Labor Review

"A fascinating exploration, for Granovetter's principal interest lies in utilizing sociological theory and method to ascertain the nature of the linkages through which labor market information is transmitted by 'friends and relatives.'"—Herbert Parnes, Industrial and Labor Relations Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Getting a Job by Mark Granovetter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Careers. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Toward Causal Models

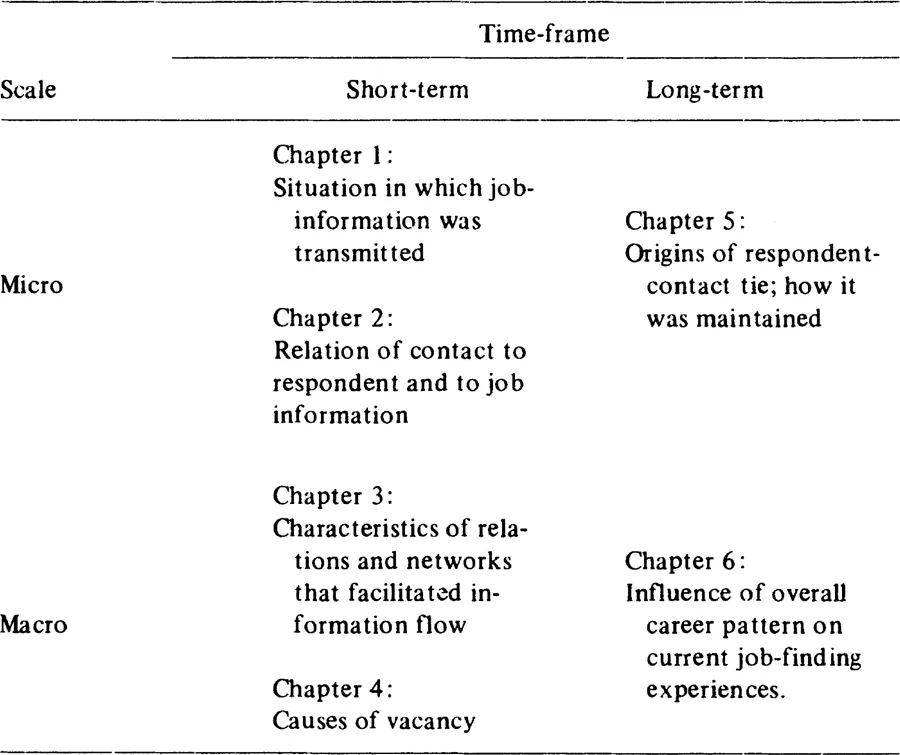

In this section of the book I will attempt to develop and explore causal explanations. The event to be explained is the acquisition of job-information by my respondents and my focus is heavily on cases where personal contacts are used. What it might mean to “explain” such an event is ambiguous. Causal investigations may be undertaken at many different levels. The first distinction of level to be made here is that of time frame. We may distinguish between immediate causes and those that operate over long time periods, comparable at least to that of a man’s average job tenure, in some cases to his entire career. Crosscutting the dimension of time is that of scale; some causes are immediate in the sense that they involve only the respondent and his personal contacts, whereas others involve individuals and jobs unknown to the respondent, possibly at considerable social distance, in a sense to be defined later. We may abbreviate these two dimensions to long-term/short-term, and micro/macro, although the dichotomies are crude. “Long-term” is really a residual category for causes that are not immediate, and “macro” has a similar relation to “micro.” Hence, both “long-term” and “macro” causes may be less long-term and less macro than many aspects of society which we are accustomed to discuss under those rubrics.

Four sequences of short-term causal questions provide the substance of Chapters 1–4. These are: 1) in what types of interpersonal situations was job information passed? The answer to this leads also to a discussion of economic theory, which labels all such situations “job search”; 2) how were personal contacts connected to respondents and to the job information which they offered?; 3) What motivated contacts to offer job information? What characteristics of interpersonal relations and networks facilitated the movement of such information from its source to its ultimate destination? 4) How did there come to be, in the first place, an opening in the job about which information was passed? These four series of questions progress from micro to macro concerns, within the short-term time frame.

Chapters 5 and 6 take up long-term causal questions. 1) How did the respondent originally become connected to the person who ultimately gave him job information? What characteristics of the individual or of his life history contributed to this connection and its maintenance? 2) What characteristics of a person’s career, of his movement through a system of jobs, affected his likelihood of finding jobs through personal contacts? Emphasis again moves, relatively speaking, from micro to macro levels. In Chapter 7 I will attempt to draw together the threads of these chapters to arrive at a somewhat integrated idea of the causal sequences involved. Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual scheme that has guided the organization of these chapters.

Figure 1. Dimensions of causality in the transmission of job information.

Chapter 1

“Job Search” and Economic Theory

There is some overlap between the subject matter of the present study and that of labor-market theory in economics. In the classical conception, labor is a commodity, like wheat or shoes, and is hence subject to market analysis: employers are the buyers, and employees the sellers of labor. Wages (or, in more refined formulations, the total benefits accruing to a worker by virtue of holding a given job) are analogized to price. Supply and demand operate in the usual way to establish equilibrium: the price of labor fluctuates in the short run until that single price is arrived at which clears the market. For homogeneous work, wage dispersion and unemployment are not possible; firms paying more than the equilibrium price for labor will thereby attract workers from firms paying less. This excess of supply over demand will drive down the price. Firms losing employees will similarly be constrained to raise wages. Workers unemployed in the short run may bid for work, driving down wages to the point where they, and those currently working, will all be employed at the new, lower equilibrium wage. This elegant package ties together wages, unemployment, and labor mobility.

Like perfect commodity markets, however, perfect labor markets exist only in textbooks. Unemployment, obviously, persists. On wage dispersion, a recent text on labor economics summarizes a number of empirical studies by saying that even “in the absence of collective bargaining, employers will continue indefinitely to pay diverse rates for the same grade of labor in the same locality under strictly comparable job conditions . . . There is no wage which will clear the market” (Bloom and Northrup, 1969:232). Reynolds, in a detailed empirical study of New Haven, concluded that labor mobility and wage determination are more or less independent; the movement of labor has little effect on wages, and “voluntary movement of labor . . . seems to depend more largely on differences in availability of jobs than on differences in wage levels” (1951:230, 233). Brown, in his study of college professors, divided disciplines into those with excess supply and excess demand for teachers. He naturally assumed that job-changers in excess-demand disciplines would have received more job offers than those in fields with excess supply. Though there was some tendency in this direction, he reports that it was “not decisive,” and that “repeated attempts to explain the differentials in market behavior by dividing the disciplines into excess supply and excess demand have not produced any conclusive evidence of the expected, usual relationships” (1965b: 117, 118n; for the basis of the excess supply and demand index see pages 87–91, 354, 361).

Several factors militate against perfect labor markets. Inertia as well as social and institutional pressures exert constraints on the free movement of labor contemplated in economic theory (cf. Kerr 1954; Parnes, 1954). Union agreements and community restraints discourage employers from adjusting wages to meet supply and demand (cf. Reynolds, chs. 7–9). The factor most relevant to the present discussion is imperfection of information.

The neoclassical theory of commodity markets generally takes the possession of complete information by market participants as one requirement of a perfect market. In Stigler’s widely cited treatment of price theory, this is described as a sufficient condition (1952:56). But it is not simple to say exactly what complete information means, as Shubik noticed (1959), in trying to construct game-theoretic models for the behavior of actors in commodity markets. Alfred Marshall, a founder of the neoclassical synthesis, hedged on the issue, saying that it was not “necessary for our argument that any dealers [buyers or sellers] should have a thorough knowledge of the circumstances of the market” (1930:334). He felt that so long as each participant behaved strictly in accord with his supply or demand schedule, the equilibrium price would ultimately be reached. He does seem, in this argument, to assume that buyers and sellers are at least aware of the identities of all those they might transact business with and even their current bid (or price)—only not necessarily their entire supply or demand schedules. Stigler comments that the “New York City market for domestic service is imperfect because some maids are working at wages less than some prospective employers would be willing to pay, and some maids are receiving more than unemployed maids would be willing to work for” (Stigler, 1952:56). This is caused primarily, one would guess, because the underpaid maids do not know the identity of very many potential employers, nor do the overpaying employers know who is available at a lower wage. Clearly, knowledge of the identities of these people is prerequisite to determining under what conditions they will offer (or purchase) services.

While there is disagreement on just how much information actually is possessed by workers in various labor markets, it seems clear that there is considerable ignorance. Reynolds holds that workers’ “knowledge of wage and nonwage terms of employment in other companies [than their own] is very meager . . . much of what workers purport to know about other companies is inaccurate” (1951:213). Even less is known about the general state of knowledge of employers; all would agree, however, that few employers know of all or most individuals who could potentially fill vacancies they have open.

Only in the last ten years have economists begun to suggest how information is obtained and diffused in markets. Most of the models presented deal with “search” behavior, the active attempts of buyers and sellers to determine each others’ identities and offers; maximization of utility by rational actors using marginal principles pervades these models. Stigler, the first to present such analyses, asserted that if “the cost of search is equated to its expected marginal return, the optimum amount of search will be found” (1961:216). In his conception, cost of search, for a consumer, is approximately measured by the number of sellers approached, “for the chief cost is time” (1961:216). He does not consider how buyers and sellers determine one anothers’ identities, an issue of particular importance in labor markets, but also with some applicability to general commodity markets. Indeed, one might want to make a clear distinction between two stages of search: 1) finding the buyers (or sellers), and 2) determining their offers. Adapting some comments of Rees (1966), we might call the first part the extensive aspect of search, and the second, the intensive. This dichotomy applies less to markets in highly standardized commodities, where the nature of an offer is as straightforward as the identity of the person making it. But in, for example, labor markets, there are many subtleties in the nature of a bid to employ or to offer services, and gathering information about each such bid may be much more time-consuming than finding out who is making bids. In practice, a job-searcher must make a tradeoff between the two aspects: the more people he discovers who are bidding, the less he will be able to find out about each bid.

Of course, some intensive activity will precede hiring, especially in higher level jobs. In commodity markets, the knowledge that a given person is offering wheat at K dollars per bushel ordinarily suffices to be sure that you will be able to buy it from him. At worst, he might sell you less than you want (wheat being entirely divisible, as classical commodities should be). But having specified an employer offering an acceptable wage, or having found an employee offering his labor at a price one is willing to pay, does not by any means guarantee the consummation of the transaction. Especially in higher-level jobs, a direct inquiry is generally felt to be necessary, in which prospective employer and employee learn more about each other and decide whether a job should be offered, and if offered, accepted.

In general, measuring the costs and benefits of search poses quite difficult problems. The proposal to consider time as the main cost (see also McCall, 1970) is more appropriate for blue-collar workers who cannot easily search during 9-to-5 jobs, than for PTM workers. A very important cost for them, on the other hand, involves their frequent use of personal contacts. In my sample, more than 80 percent of the personal contacts used not only told the respondent about his new job, but also “put in a good word” for him. Contacts cannot be asked to do this too often without the respondents’ using up their “credit” with them, straining the relationship. There are, moreover, as Brown points out, opportunity costs in searching for a particular job (or employee): one may necessarily forego searching for others (Brown, 1965b: 187). Brown’s model, similar to Stigler’s in its assumptions of optimal search behavior, allows for these other costs (1965b: 185–198). His formulation, however, could be operationalized only via extensive survey data.

Similar difficulties arise on the benefit side; all models found measured benefits in money terms (Stigler, 1962; Brown, 1965b; McCall, 1965, 1970). Stigler and McCall recognize that the future benefits of the present search must be taken into account. McCall interprets this primarily in terms of expected length of employment in a job; Stigler’s more general formulation points out that if current price offers are correlated with future ones, information now found also has future benefits. Each suggests appropriate discounting procedures. No attempts are made, however, to specify the value in the future of holding a particularly prestigious job now. More relevant, even, from the point of view of my study, no attempt is made to assess the value of contacts acquired in a particular position. This may be psychologically a minor factor; many of my respondents had never realized, until the time of interview, how much of their career was mediated by personal contacts acquired in previous jobs; but the actual benefits may be considerable, as discussed later on in Chapters 5 and 6.

The primary contribution of the present study to this discussion lies in an analysis of the notion of “search,” as viewed from the supply side of labor markets. Of the authors surveyed, only Brown tries to work into his theory the idea that different methods of search yield different amounts of information. Brown’s idea is that job-seekers, in effect, compute costs and benefits for each method they might use. That method with the highest expected net benefit is used first; then all calculations are repeated, and the searcher chooses a method for his second try. Search continues until marginal benefits equal marginal cost. Time, in this model, is effectively omitted as a parameter, since after any method is used, the next time period is assumed to begin (1965b: 191–198).

While this account is closer than others to my empirical findings on labor-market behavior, it is nevertheless inadequate. One of my original motives in choosing a PTM sample for study was, in fact, my interest in observing sophisticated search procedures; I assumed that if anyone would be likely to search in a careful, effective way, it would be people in PTM jobs. My results, however, lead me to doubt that information in labor markets, at least in PTM markets, is diffused primarily by “search.”

For blue-collar markets, Reynolds holds that “the core of the effective labor supply at any time . . . consists of . . . people who are entering the market for the first time, who have been ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Toward Causal Models

- Part Two: Mobility and Society

- Afterword 1994. Reconsiderations and a New Agenda

- Appendix A. Design and Conduct of the Study

- Appendix B. Coding Rules and Problems

- Appendix C. Letters and Interview Schedules

- Appendix D. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness

- Notes

- References

- Index