- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In August 1934, young Cyril L. wrote to his friend Billy about all the exciting men he had met, the swinging nightclubs he had visited, and the vibrant new life he had forged for himself in the big city. He wrote, "I have only been queer since I came to London about two years ago, before then I knew nothing about it." London, for Cyril, meant boundless opportunities to explore his newfound sexuality. But his freedom was limite: he was soon arrested, simply for being in a club frequented by queer men.

Cyril's story is Matt Houlbrook's point of entry into the queer worlds of early twentieth-century London. Drawing on previously unknown sources, from police reports and newspaper exposés to personal letters, diaries, and the first queer guidebook ever written, Houlbrook here explores the relationship between queer sexualities and modern urban culture that we take for granted today. He revisits the diverse queer lives that took hold in London's parks and streets; its restaurants, pubs, and dancehalls; and its Turkish bathhouses and hotels—as well as attempts by municipal authorities to control and crack down on those worlds. He also describes how London shaped the culture and politics of queer life—and how London was in turn shaped by the lives of queer men. Ultimately, Houlbrook unveils the complex ways in which men made sense of their desires and who they were. In so doing, he mounts a sustained challenge to conventional understandings of the city as a place of sexual liberation and a unified queer culture.

A history remarkable in its complexity yet intimate in its portraiture, Queer London is a landmark work that redefines queer urban life in England and beyond.

Cyril's story is Matt Houlbrook's point of entry into the queer worlds of early twentieth-century London. Drawing on previously unknown sources, from police reports and newspaper exposés to personal letters, diaries, and the first queer guidebook ever written, Houlbrook here explores the relationship between queer sexualities and modern urban culture that we take for granted today. He revisits the diverse queer lives that took hold in London's parks and streets; its restaurants, pubs, and dancehalls; and its Turkish bathhouses and hotels—as well as attempts by municipal authorities to control and crack down on those worlds. He also describes how London shaped the culture and politics of queer life—and how London was in turn shaped by the lives of queer men. Ultimately, Houlbrook unveils the complex ways in which men made sense of their desires and who they were. In so doing, he mounts a sustained challenge to conventional understandings of the city as a place of sexual liberation and a unified queer culture.

A history remarkable in its complexity yet intimate in its portraiture, Queer London is a landmark work that redefines queer urban life in England and beyond.

"A ground-breaking work. While middle-class lives and writing have tended to compel the attention of most historians of homosexuality, Matt Houlbrook has looked more widely and found a rich seam of new evidence. It has allowed him to construct a complex, compelling account of interwar sexualities and to map a new, intimate geography of London."—Matt Cook, The Times Higher Education Supplement

Winner of History Today's Book of the Year Award, 2006

Winner of History Today's Book of the Year Award, 2006

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Queer London by Matt Houlbrook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Modern British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780226354620, 9780226354606eBook ISBN

9780226788272PART 1

POLICING

Figure 3. Map, “This Is London.”

1

REGULATION

THE LAW

It is received wisdom that, as Liz Gill put it in the Guardian recently, “being gay was illegal” until the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.1 If the statement is misleading in its conception of the law, it nonetheless highlights the accumulated battery of legal provisions designed or utilized to suppress sexual, social, or cultural interactions between men in the first half of the twentieth century. As Harry Cocks demonstrates, the offences of buggery and indecent assault evolved within common and statute law from the late eighteenth century to encompass any homosexual encounter, wherever it had occurred, and whether or not the men involved had consented.2 These provisions were codified and elaborated in the late nineteenth century. Sections of the Offences against the Person Act (1861) dealing with buggery and indecent assault were followed by the notorious section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885), defining any act of “gross indecency” between men in “public or private” as an offence.3 Statute law was, moreover, complemented by the offence of “indecency” under many local bylaws.4

These narrowly defined sexual offences were supplemented by a series of provisions that targeted wider social and cultural practices. Responding to anxieties about the condition of London’s streets, the Vagrancy Law Amendment Act (1898) and the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1912) introduced the public order offence of “persistently importuning for an immoral purpose,” which attempted to suppress queer men’s use of public space for “cruising” and social interaction.5 Generalized public order statutes and licensing provisions, moreover, notionally made it an offence for a commercial venue to tolerate queer men’s presence. It was never illegal simply “to be gay,” but the law criminalized a series of discrete social, sexual, and cultural practices in which men might participate.6

The formal regulation of male sexual and social behavior was thus structured around a dual logic. Although the introduction of legislation was often ad hoc and haphazard, in practice the law constituted a pervasive system of moral governance, defining sexual “normality” through the symbolic ordering of urban space. Acceptable sexual conduct was defined around the bourgeois nuclear family—private, between adult “heterosexual” married couples. Legislation against homosex thus echoed that against prostitution or public sex—in Philip Hubbard’s phrase, making “dominant moral codes clear, tangible and entrenched, providing a fixed point in the attempt to construct boundaries between good and bad subjects.”7 In so doing, the law collapsed the conceptual distinctions between public and private that, notionally, went to its very heart. As Leslie Moran suggests, public space was understood as the realm of law’s full presence—“a space of order and decency through the law.” The private, by contrast, was “an alternative place where the law is absent.”8 The law’s “absence,” however, was contingent upon conforming to notions of normative sexual and social behavior. The “bad subject”—the sexual deviant—remained subject to state intervention, and was deemed sufficiently dangerous as to warrant intrusion into the sanctified private sphere.

For queer men, these provisions had profound implications, for the law threatened to follow them into the intimate, prosaic, and ubiquitous spaces of everyday urban life. If they looked for partners in the street or park or simply had sex in their own home, they could be arrested, prosecuted, imprisoned for up to ten years, and—in certain cases—whipped. If they met friends in a café they could be caught up in a police raid, their names taken, and the venue closed. The formal technology of surveillance institutionalized and embodied by the law suggested that the British state was unwilling to tolerate any expressions of male same-sex desire, physical contact, or social encounter. In all its erotic, affective, and social relations the queer body—and the spaces it inhabited—was a public body, subject to the draconian force of law. De jure, the modern metropolis held no place for the queer.

To read queer men’s experiences of the law from its formal provisions, however, fails to comprehend the complex and often contradictory ways in which legislation was implemented. Only through the intermediary agencies of municipal governance established in the nineteenth century—the Metropolitan Police (the Met), the London County Council (LCC), the Metropolitan Borough Councils, and the Military Authorities—did that legislation acquired tangible significance.9 Rather than what it said, the issue becomes how, and with what effects, was legislation translated into practice on London’s streets. How was the law embodied through the daily routine of police operations?

While queer urban cultures were subject to surveillance by a diverse range of agencies, this chapter focuses upon the operations of the Met and, in particular, their enforcement of the sexual offences laws. It was in London’s public spaces and through the figure of the policeman that queer men most often encountered the law. The Met were always most active in policing men’s behavior, providing information to all other agencies. Moreover, this case study highlights the tensions between legislative pronouncements and the realities of regulation. I will return to the policing of commercial venues and the activities of other official agencies throughout part 2, setting shifting forms of regulation against the changing organization of queer sociability. My argument here—elaborated in the chapters that follow—is simple: policing was idiosyncratic and contingent, rendering specific practices and places invisible while bringing others into sharp relief. The de jure exclusion of queer men from metropolitan London collapsed amidst the operational realities of modern police systems.

THE POLICE

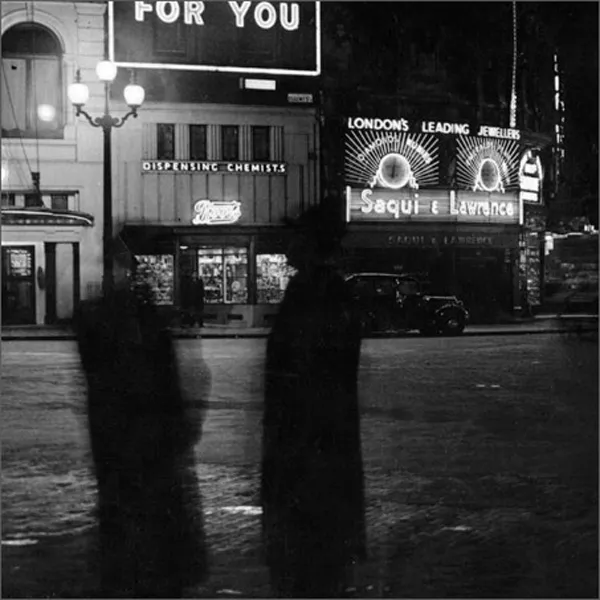

To explore the operationalization of the sexual offences laws means reconstituting the cognitive landscape inhabited by individual policemen, the maps through which they organized and understood their own movements across the city. The legal and administrative rules governing policing, as well as the informal knowledge officers gained through experience on the ground, interacted to produce an imagined geography of sexual transgression that defined whom the queer was, where he was to be found, and how he could be apprehended.

Crucially, while legislation collapsed the conceptual distinction between public and private, that logic did not extend to the procedural rules defining the Met’s formal operational domain. The result, in Nick Fyfe’s terms, was “a set of significant steering constraints of structural importance for [their] time-space deployment.”10 The physical, cultural, and administrative barriers constructed around the home created a de facto private space. Officers could only enter residential spaces with a search warrant. In detecting private sexual offences, the Met thus relied upon public complaints or secondhand information. That the police never made any concerted attempts to pursue the queer into his home placed men’s behavior there almost beyond the law: “such acts,” the director of public prosecutions (DPP) admitted in 1954, “are unprosecutable.”11 Access to commercial venues was similarly circumscribed, possible only under particular conditions. These formal “steering constraints” confined the policeman’s habitual beat to London’s streets and open spaces.12

Working within these jurisdictional parameters, senior and divisional officers thus established administrative definitions of importuning, gross indecency, and indecent assault that oriented patrols towards public queer spaces, mapping legal offences firmly onto particular urban sites. In Hyde Park, for example, beat officers were directed to the Meeting Ground and Hyde Park Corner.13 Under these formal definitions the public urinal was identified as the locus of sexual offences. Asked to report on “homosexuality” in the West End in 1952, C Division police officers simply listed the urinals where men could be found.14 This formal correlation between geography and criminality was, moreover, constantly reproduced at the divisional level. In 1933, for example, the attention of officers at Tower Bridge station was drawn to one Bermondsey urinal “by notes in the rough book.”15 The administrative conventions of policing articulated a narrow operational field that, for the most part, placed alternative sites of queer sexual and social interaction outside surveillance.

Within these formal constraints, the enforcement of the law depended upon the everyday movements of individual officers. Immersed in their operational environment, policemen became ever more familiar with the spatial and cultural organization of queer life, gaining the informal knowledge allowing them to interpret and implement legislation. As one officer was told during a 1932 raid on a ballroom, “you know what kind of boys we are.”16 The importance of knowing these “kind of boys” to policing is clear from the experiences of Police Constable (PC) 89/E Reginald Handford. Handford joined the Met in 1925, transferring to Bow Street station the following year at the age of twenty-two. There he became part of a group of twelve plainclothes policemen employed in the “detection of crime” in the district around the Strand.17

Handford learned to police from his more experienced colleagues—Cundy, Mogford, Shewry, Hills, and Slyfield—drawing upon their accumulated experience dealing with sexual offences. In part, officers became increasingly sensitized to the visual signifiers of character that allowed them to differentiate the queer from the fluid urban crowd. The effeminate quean became a working definition both of the queer himself and the perpetrator of a sexual offence, his body a demonstrable sign of deviant intent. While Handford, for example, recognized that “there are different forms of sodomites” and, indeed, arrested one man who “had no outward indication of his nefarious habits,” he clearly visualized the transgressive male body in a particular way.18 When asked, “have these male importuners . . . anything distinctive about them?” he replied immediately, “Yes, painted lips, powder.”19 On the beat, this image oriented officers towards individuals and commercial venues. In 1926, for example, Slyfield and Mogford were inside the Strand Hotel Restaurant when Frank W. drew their attention because of his “heavily powdered” face. They watched him cruising in other bars, on the Strand, and in Villiers Street before arresting him for importuning.20 Within such mentalities, sexual offences could be defined as transgressions of acceptable masculine styles, leaving conventionally dressed men and the venues they frequented invisible.

The sensitivity of Slyfield and Mogford to the minutiae of self-presentation suggests a further geographical coding of sexual transgression. To put it another way, their experience produced a detailed cognitive map that defined sexual offences as place-specific. While Frank W. may have moved unnoticed outside the West End, in a district imagined as a site of sexual disorder and vice his body drew suspicion. Indeed, the officers’ presence in certain venues on the Strand indicates how policing was organized not just by knowledge of who the queer was but also where he could be found. Sexual deviance—and consequently, police surveillance—was, in part, mapped onto the Strand’s commercial spaces and places like the Coliseum Theatre.21 Despite this, procedural constraints and their immersion in public urban life focused officers’ attention upon the streets, parks, and above all, urinals frequented by queer men. If street cruising was fluid and mobile, urinals were fixed and physically bounded—as well as being administratively defined—and therefore easy to keep under surveillance. In 1927, almost all of the arrests made by E Division officers arose in fifteen local urinals—places like Durham House Street, Taylor’s Buildings, York Place, and Cecil Court.22

This local geography of sexual transgression was clearly established by 1917, inherited and elaborated by successive generations of beat officers, and becoming central to occupational definitions of masculinity and competency. The good policeman, quite simply, knew his “ground.”23 Within this milieu Handford, apparently, learned quickly. Through conversation he became aware of the Coliseum’s reputation and the “importuners” around Charing Cross. On the beat, colleagues introduced him to the “public house[s] sodomites are frequenting.” He knew of the blackmailers operating in the neighborhood and the men who had sex under the arches of the Adelphi. He recognized the “convicted sodomites” he encountered. He identified “four urinals which are used by these sort of people,” having “discussed . . . the prevalence of this particular crime at this particular place with Slyfield [and] Mogford.” Drawing upon this remarkable familiarity with local queer culture, he focused his own attentions on one “notorious urinal” in the Adelphi Arches—“always frequented by certain sodomites.” Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Terminology

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: This Is London

- Part 1: Policing

- Part 2: Places

- Part 3: People

- Part 4: Politics

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Queer Incidents Resulting in Proceedings at the Metropolitan Magistrates’ Courts and City of London Justice Rooms, 1917–57

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index