- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As cities grow and climates change, precipitation increases, and with every great storm—from record-breaking Boston blizzards to floods in Houston—come buckets of stormwater and a deluge of problems. In Stormwater, William G. Wilson brings us the first expansive guide to stormwater science and management in urban environments, where rising runoff threatens both human and environmental health.

As Wilson shows, rivers of runoff flowing from manmade surfaces—such as roads, sidewalks, and industrial sites—carry a glut of sediments and pollutants. Unlike soil, pavement does not filter or biodegrade these contaminants. Oil, pesticides, road salts, metals, automobile chemicals, and bacteria all pour into stormwater systems. Often this runoff discharges directly into waterways, uncontrolled and untreated, damaging valuable ecosystems. Detailing the harm that can be caused by this urban runoff, Wilson also outlines methods of control, from restored watersheds to green roofs and rain gardens, and, in so doing, gives hope in the face of an omnipresent threat. Illustrated throughout, Stormwater will be an essential resource for urban planners and scientists, policy makers, citizen activists, and environmental educators in the stormy decades to come.

As Wilson shows, rivers of runoff flowing from manmade surfaces—such as roads, sidewalks, and industrial sites—carry a glut of sediments and pollutants. Unlike soil, pavement does not filter or biodegrade these contaminants. Oil, pesticides, road salts, metals, automobile chemicals, and bacteria all pour into stormwater systems. Often this runoff discharges directly into waterways, uncontrolled and untreated, damaging valuable ecosystems. Detailing the harm that can be caused by this urban runoff, Wilson also outlines methods of control, from restored watersheds to green roofs and rain gardens, and, in so doing, gives hope in the face of an omnipresent threat. Illustrated throughout, Stormwater will be an essential resource for urban planners and scientists, policy makers, citizen activists, and environmental educators in the stormy decades to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stormwater by William G. Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226365008, 9780226364957eBook ISBN

9780226365145Part I

Urban Conditions

Chapter 1

More people, more pavement

Out in the Arizona desert in the midst of a storm, there’s stormwater. So-called soils in that area feel and act like concrete surfaces, and it’s a wonder that plants can even find a toehold. But when it comes to rain, the drops just splat on the surface, with the first few drops wetting the dry surface, perhaps with some evaporation, all the remaining rain runs downhill, collects in channels, and comes rushing through long-scoured stream beds. Seemingly very little water infiltrates into the “soil” despite the welcome of the wonderful cactus forests in the region.

In this desert backdrop, building a house or road with surfaces that don’t allow rainwater infiltration isn’t much of a change for stormwater: rain doesn’t infiltrate those surfaces either, and the only change might be some vegetation loss.

Contrast this with nearly any other area of the country besides these deserts. Here in Durham, North Carolina, I’ve seen two inches of rain disappear into the ground during a dry spell in spring. Vegetation grabs a bit on leaf surfaces and bark, some evaporates away to cool surfaces, but much of it flows through the pores and channels in dry soils emptied of any water. Flowing quickly downward, this precipitation makes up for water lost through the transpiration of abundant vegetation that pulls water through plant tissues and out, as vapor, through open stomata on leaves, enabling the absorption of carbon dioxide and formation of more plant tissue.

Build houses or roads in this area, and the entire soil surface changes to one that’s impervious to the infiltration of water. Development seals off soil channels to the downward flow of water, causing rains to wash surfaces clean of pollutants and to flow and collect downhill into large quantities, creating flashy flows like those in the desert. Anything that intercepts raindrops before they hit the ground counts as an impervious surface: parking lots, roofs, roads, sidewalks, even umbrellas count against our landscape alterations.

Though true in a sense, that definition would mean that trees and their leaves could count as impervious surfaces, but that water is needed for growth, one of nature’s benefits welcomed like the water collected by people using roofs to fill cisterns. Rain falling on those structures counts as a resource, by humans or nature, something desired and valued, to be concentrated for its beneficial uses like drinking, washing, and watering crops and animals.

It’s counterintuitive to think of water as a pollutant. We drink it, we bathe in it, we water our gardens and crops with it. But a flood of it in our homes and cities leads to problems with terrible consequences.

Water collected in the depressions of Durham’s Carolina clay, for example, turns into a forbidding mess for any and all footed creatures or wheeled vehicles, leaving puddles where mosquitoes hatch in about three minutes. In excess, water becomes an undesirable pollutant, something to be hurried downhill and out of the way. The great flush of high water volume from impervious urban surfaces then scours and erodes streams, washing away the organisms and, after the water’s gone by, drying out streamside habitats. As with our structures, too much water harms natural systems as well, or at least disturbs these systems in new ways.

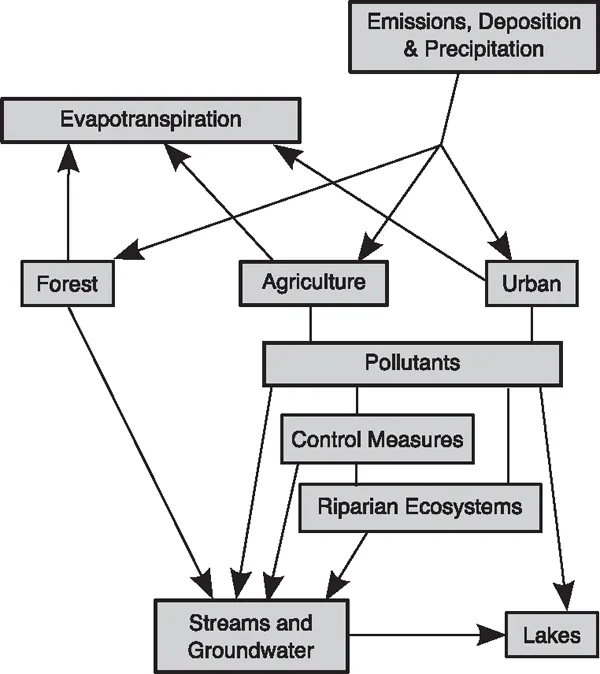

This book broadly covers the science behind stormwater. Part I examines the background conditions of the water cycle, emissions and depositions of pollutants, and the basics of land use patterns that create impervious surfaces. Part II covers the harms brought on by stormwater, beginning with the runoff itself, covering the various associated harms, including contaminants and thermal pollution, and finishing with an overview of the organismal and ecosystem responses. Part III considers a small sampling of solutions for the problems, with an emphasis on the ecosystem services provided by streams and riparian systems, as well as coverage of constructed stormwater control measures. I provide a particular emphasis on landscape-distributed measures that fall under the guise of low-impact development.

Facets of stormwater.

Figure 1.1: Summary of stormwater-related aspects of the water cycle. Part I examines rainfall and atmospheric deposition onto various land use types, setting the background conditions for the various environmental harms, indicated by “pollutants,” to surface waters discussed in Part II. Part III covers solutions to these harms through the use of riparian ecosystems and stormwater control measures.

For hundreds of millions of years, rain fell and nobody cared, mainly because there were no people. Then, for a couple million more years, rain fell, but people still didn’t care, except when the rain didn’t fall. Today, our dramatically larger human population causes all of the environmental problems that we talk about, and the recent population increase has indeed been invasive. When my oldest grandparent was born in 1888, there were just one to two billion people in the world. Now there are more than 7.2 billion people.1 Our global human population increased sixfold in 130 years, just a few generations, and proportional with that increase grew energy use, chemical emissions, land use changes, impervious surfaces, water use, and crop production.

All these people, mostly concentrated into cities, put tremendous stresses on our natural ecosystems. In particular, our large population affects stormwater because modern human land use changes the flow of water, and the really damaging pollutants come about from people and their activities—the more people, the more pollutants. When precipitation falls on the impervious surfaces that characterize urbanization, the water makes its way through constructed stormwater systems to urban streams.1 The impervious surfaces of cities create stormwater, which produces high peak flows and low base flows and, along with the pollutants carried with those flows, leads to bioaccumulation, toxicity to organisms, and poor habitat quality. These effects of urbanization also kill sensitive organisms living in urban streams. Sensitive species represent a set of organisms clearly separate from tolerant species when examined along an axis representing urbanization.2

Gaining a better understanding of stormwater science benefits from a basic discussion of the water cycle, parts of which are characterized in Figure 1.1, with more details covered in Chapter 2. It’s a cycle, and since I often wish it would rain, let’s start there. Rain falls on the ground and then has several fates. First, either it can go back up into the air by evaporation—turning into a vapor and becoming part of the atmosphere once again—or it can be drawn into a plant’s roots to become part of its sap, destined to evaporate out of one of the plant’s many stomata, a process called transpiration. Evaporation and transpiration, taken together, are called evapotranspiration. A little bit of the water in plants gets split apart and transformed into plant tissue, becoming a part of the biosphere. Rain can also soak into the ground, immediately becoming groundwater, or it could flow along the surface, collecting as it moves downhill, thereby being labeled stormwater, eventually merging with a nearby stream or water body. As we’ll discuss later, streams and groundwater interact strongly. Water can also evaporate from streams, lakes, and oceans.

Keep in mind the many different types of “used” water: stormwater, wastewater (or sewage), groundwater, drinking water, and reservoirs. Rain falling on permeable surfaces like forests and prairies soaks in and can recharge groundwater sources, though heavy rainfalls can cause water to run off these surfaces. In contrast, rain that falls on impervious surfaces automatically becomes stormwater because it has no allowance for infiltration. Water running off of surfaces—called overland flows—becomes stormwater, often draining to streams that connect with rivers to refill lakes, reservoirs, or oceans. Lakes and reservoirs recharge from water flowing through streams, including stormwater flushed into urban streams. Wastewater originates from our houses, businesses, and hospitals, flushed down toilets, showers, and sinks, partly cleaned while passing through wastewater treatment plants before entering streams. Yet another term is gray water, which means water coming from sinks, washing machines, and, perhaps, also showers and bathtubs becomes a resource used for underground irrigation of shrubs and trees, an option allowed in some jurisdictions. Groundwater, which we’re most familiar with from wells drilled into aquifers, includes the water within aquifers and the moisture in the unsaturated vadose zone. Groundwater recharges by rainwater filtering through the ground throughout watersheds. Drinking water can come from both reservoirs and groundwater sources.

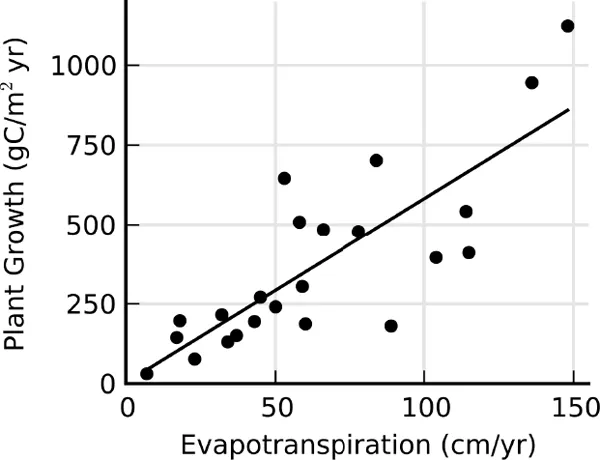

Water and warmth make plants grow.

Figure 1.2: Plant growth, more formally called net primary productivity (NPP), increases across 23 ecological areas across the globe with increasing levels of evapotranspiration, which combines water availability and warmth (after Cleveland et al. 1999).

At various places in the water cycle, water can be stored. Lakes, ponds, and aquifers are obvious places, but so are puddles, leaf surfaces, and cisterns. Each storage pool affects how water flows, as well as ground and air temperatures because of the cooling brought about by evapotranspiration.

Our topic here is stormwater, but our large human population needing food leads to agricultural practices deeply dependent on water, fertilizers, and technology. Regarding the first of these factors, Figure 1.2 uses data from 23 vastly differen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: Urban Conditions

- Part II: Environmental Harms

- Part III: Solutions

- Appendix: U.S. Stormwater Laws

- Notes

- References

- Place Index

- Topic Index

- Acronym Index