eBook - ePub

Communities of Style

Portable Luxury Arts, Identity, and Collective Memory in the Iron Age Levant

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communities of Style

Portable Luxury Arts, Identity, and Collective Memory in the Iron Age Levant

About this book

Communities of Style examines the production and circulation of portable luxury goods throughout the Levant in the early Iron Age (1200–600 BCE). In particular it focuses on how societies in flux came together around the material effects of art and style, and their role in collective memory.

Marian H. Feldman brings her dual training as an art historian and an archaeologist to bear on the networks that were essential to the movement and trade of luxury goods—particularly ivories and metal works—and how they were also central to community formation. The interest in, and relationships to, these art objects, Feldman shows, led to wide-ranging interactions and transformations both within and between communities. Ultimately, she argues, the production and movement of luxury goods in the period demands a rethinking of our very geo-cultural conception of the Levant, as well as its influence beyond what have traditionally been thought of as its borders.

Marian H. Feldman brings her dual training as an art historian and an archaeologist to bear on the networks that were essential to the movement and trade of luxury goods—particularly ivories and metal works—and how they were also central to community formation. The interest in, and relationships to, these art objects, Feldman shows, led to wide-ranging interactions and transformations both within and between communities. Ultimately, she argues, the production and movement of luxury goods in the period demands a rethinking of our very geo-cultural conception of the Levant, as well as its influence beyond what have traditionally been thought of as its borders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Communities of Style by Marian H. Feldman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Workshops, Connoisseurship, and Levantine Style(s)

While the Group 2 bridle harness is obviously Phoenician in style and form, the Group 1 examples are more problematic. The style is heavier and clumsier than the “classic Phoenician” Group 2 pieces and has more of a Syrian feel. However, the spade-shaped blinkers and hinged frontlets belong to a western tradition of bridle harness rather than the very different Syrian tradition, with its smaller sole-shaped blinkers and triangular frontlets.

—G. Herrmann and Laidlaw 2009, 82

How do “in-between” ivories, such as the so-called Group 1 horse bridle frontlets cited above, found in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, challenge our attempts at locating places of production for early Iron Age Levantine portable luxury arts (fig. 1.1)? How does the in-betweenness of their stylistic evidence impact the equation of style with workshop/place of production? Not fitting clearly into either the Phoenician or the North Syrian stylistic groups, and not forming any coherent stylistic subgroup within these two main classifications,1 the “Group 1” frontlets problematize our application of the connoisseurial method to first-millennium Levantine ivories.

Fig. 1.1 “Group 1” horse-bridle frontlet from Well AJ, Northwest Palace, Nimrud. Baghdad, Iraq Museum, IM 79579. In G. Herrmann and Laidlaw 2009, no. 246. Courtesy of The British Institute for the Study of Iraq (Gertrude Bell Memorial).

Scholarship on early first-millennium Levantine arts has focused largely on attributional pursuits, because the vast majority of presumed Levantine works has been found outside the area of the Levant proper. The situation is particularly acute for the ivories; scholars have long recognized that the archaeological context in which the largest number of them were excavated—the Assyrian royal city of Nimrud—was not the place of their cultural source (that is, they were not produced in an Assyrian style).2 In addition, their large numbers—in the thousands—exhibit a diverse array of visual and formal similarities, which seem to hold out the promise that distinct stylistic groupings might be discerned.3 Although elements such as iconography, object genre, and technique have been brought to bear on the question, style (in its many different guises) is considered the most telling with respect to location of manufacture.4 Thus, connoisseurial approaches have long been viewed as a means to assign the ivories to specific locations of production. Yet, as our connoisseurial precision has increased over the years, the number of complications—of “in-betweens”—has only grown; with the delineation of new stylistically based groups, exceptions to these groups have come into focus and require explanation.5 It is these exceptions and in-between examples that motivate me in this initial chapter to rethink early Iron Age Levantine luxury art production along lines that do not depend on a concept of workshop production bound to city-state polity.

To do so, it is helpful first to review the scholarship that forms the foundation of studies into early Iron Age Levantine art production, and thus this chapter is largely historiographic. In particular, it reviews the scholarship on Levantine ivories, charting the use of connoisseurship from the mid-nineteenth century onward.6 The application of this methodology has been central to the study of these arts, and it is therefore worth considering some of its implications and assumptions when applied to Levantine ivories. The close stylistic analysis associated with connoisseurship remains a critical tool, and indeed has allowed scholarship to advance to the point at which we can now address the problem of exceptions; without the definition of style groups, those pieces that constitute “in-betweens” would remain intellectually invisible. At the same time, there are assumptions implicit in connoisseurship relating to the organization of artistic production that I believe need to be unpacked in order to resolve the issues raised by the exceptions. In particular is the assumption that each Levantine political city-state had its own, stylistically coherent and independent workshop. I propose instead that the stylistic analysis of Levantine ivories points away from a geopolitical spatial mapping of the ivories; rather, a lack of clear stylistic boundaries emerges that is suggestive of networked practices rather than isolated production loci.

First-Millennium Levantine Ivories

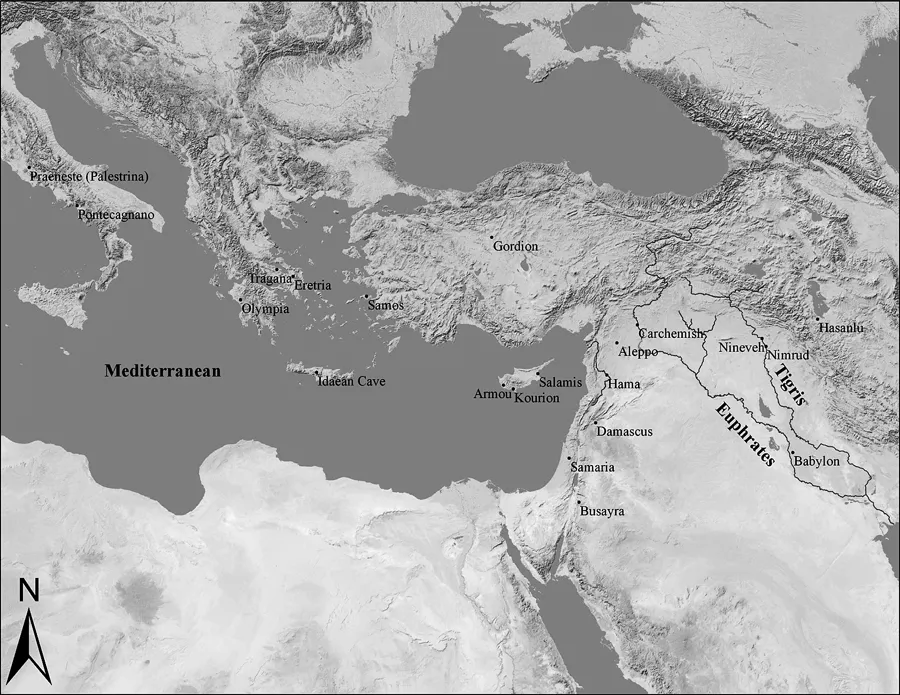

The first ivories (as well as bronzes) were discovered at Nimrud in the 1840s and 1850s, which remains the site of the highest concentration of ivories to date; thousands have been excavated there over the course of nearly 150 years of digging, with substantial new corpora discovered in the 1950s and 1970s.7 Far smaller quantities of stylistically related ivories have been found in the greater Levantine area, as well as occasional examples in more distant locales, including Hasanlu in northwest Iran, Cyprus, Greece, and Etruria (maps 1 and 2).8 It is in fact the diffuse nature of the ivories, in terms of both their stylistic delineations and their distribution patterns, that motivates and continues to challenge attribution to specific place and time. From the initial perplexity in the mid-nineteenth century, increasingly exacting criteria for sorting and classifying the ivories have allowed us to make sense of the dizzying number and stylistic diversity of the material. The classificatory trajectory has moved from gross cultural distinction to more precise regional groupings. This, in turn, has led to ever more careful delineation of style-groups, which somewhat paradoxically has revealed a lack of hard boundaries between style-groups at the level of higher resolution.

Sir Austen Henry Layard, soon after excavating the first examples in the 1840s, identified the ivories as non-Assyrian.9 His comparative data at that time was extremely limited, and he proposed an Egyptian source, though he argued for manufacture at Nimrud (by captured artisans) specifically for the patronage of the Assyrian kings. With the expanding corpus of comparative materials, later nineteenth-century scholars argued for Phoenician production. In 1912, Frederick Poulsen proposed that the non-Assyrian ivories in fact represented the products of more than one cultural origin. In a distinction that continues to be accepted today, he divided the Nimrud ivories into two groups, linking those with more Egyptianizing elements to Phoenicia (understood as the central Levantine coastal region, more or less congruent with the modern nation-state of Lebanon) and another group to the carved reliefs of North Syria (which he called Hittite).10 Poulsen’s early work has been expanded subsequently and more systematically argued by Richard Barnett, Irene Winter, and Georgina Herrmann.

Map 1 Near East and eastern Mediterranean, showing sites mentioned in text. Map created by Martin Weber; © Marian H. Feldman 2013.

Barnett, assigned the task of publishing the ivories from Nimrud owned by the British Museum, formed two main groups of ivories based first of all on archaeological findspot: those excavated by Layard in the 1840s in the Northwest Palace and those excavated in the 1850s by William Kennet Loftus in the so-called Southeast Palace, later renamed the Burnt Palace.11 These archaeological contexts appeared to Barnett to map over the major stylistic distinctions made by Poulsen, with the Layard ivories being primarily Phoenician and the Loftus group generally Syrian. Within the Loftus group, he further subdivided the ivories into those that lacked Egyptian features, which he attributes “almost certainly to Syrian manufacture,” and those exhibiting some Egyptian features, which he nevertheless sees as “by Syrian artists in the Phoenician manner.”12 The “certain Syrian” ivories are characterized, according to Barnett, by the facial features of the humans (“an oval face with a flat crown but a high forehead; an usually sharp and prominent nose, a small mouth with pursed lips, and large almond eyes with small pupils”) and the rendering of the musculature of the lions and lion-based sphinxes and griffins (“stylized superficially into an ornamental linear pattern merely stressing the curves of the muscles”).13 Barnett further proposes that Hama (ancient Hamath) was the principal center of ivory carving in the region, attributing the Loftus ivories to this southern Syrian city-state.14 Though he admits the difficulty in pinpointing a single city as the location for the manufacture of the Layard group of Phoenician-style ivories, he sets forth a rather weak hypothesis to link this collection to Hamath as well, based on a rereading of a complicated Egyptian hieroglyphic cartouche found on one of the ivories.15

Map 2 Greater Levantine region, showing sites mentioned in text. Map created by Martin Weber; © Marian H. Feldman 2013.

Following on Barnett’s work, in the 1970s Winter provided more quantifiable evidence for the geographic distinction between Phoenician- and North Syrian–style ivories.16 Working from the basic stylistic classification first proposed by Poulsen and then strengthened by Barnett, Winter plotted the findspot locations of the two ivory groups onto maps of the Near East and eastern Mediterranean. Her resulting distribution maps show a clustering in more northerly sites for the North Syrian–style ivories and in more southerly sites for Phoenician-style ivories, thus indicating to Winter a real geographic basis for these stylistic designations. As a correlate to this, the two styles are rarely found at the same site aside from a few examples (Nimrud, Lindos, and Samos), which Winter explains through their specific historical situations.17 Based on these patterns, Winter argues that Barnett’s attribution of both styles to Hamath cannot be correct, and moreover that “the two areas operated in reasonably separate spheres of contact and influence.”18 Distribution maps are, however, not without their own set of challenges. This is evident, for example, in the way that differences between the two groups get flattened, because each particular ivory must be assigned “either-or” to one stylistic classification or the other without consideration of degrees of variation along a spectrum of difference.19 Yet the individual pieces exhibit a high degree of stylistic variability among themselves. The necessity of assigning an ivory to either the North Syrian or the Phoenician stylistic category is therefore unable to account for the subtle graduations along the spectrum from North Syrian to Phoenician (generally understood as ranging from fewer to more Egyptianizing traits) that mark these ivories—the “in-betweens.”

Winter confronted this very problem of variability soon after in her analysis of a series of ivories that exhibits a blending of the two styles within the same piece (plate 1).20 These she assigned to the South Syrian region and specifically to the city-state of Damascus on the basis of ivories found at Arslan Tash, which although located in North Syria include one piece—undecorated—that bears an inscription naming Haza’el, who is taken to be the same Haza’el as the ninth-century Aramaean king of Damascus.21 In this she follows the lead of Barnett, who had previously argued that a group of metal bowls found at Nimrud might be assigned to an Aramaean school of art due to their inscriptions of Aramaic personal names.22 Stylistically, these bowls commingle features that are typically separated between either the North Syrian or the Phoenician styles. Winter, however, sees these bowls as including independent elements of each style rather than truly merging the two styles. The Arslan Tash ivories, on the other hand, display a hybridized integration of Phoenician and North Syrian stylistic traits. Winter argues that this seamless blending of features characterizing North Syrian and Phoenician ivories perfectly aligns with what one might expect to find in the geographic area between North Syria and Phoenicia. The question of individual bowls exhibiting elements of both styles side-by-side is not addressed, yet is an intriguing situation that Francesca Onnis has recently studied and that I discuss below.

With the refinement of the ivories’ stylistic classification into broad regional styles, including a Phoenician, North Syrian, and South Syrian/Intermediate tradition23 in addition to an Assyrian one, attention has turned to locating more precise places of production. At this level, the concept of workshops is usually invoked; these are generally taken to be synonymous with specific politically known city-states.24 For attributing ivories to individual workshops, Herrmann’s influence has been particularly prominent in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Note

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Workshops, Connoisseurship, and Levantine Style(s)

- 2. Levantine Stylistic Practices in Collective Memory

- Color Plates

- 3. Creating Assyria in Its Own Image

- 4. Speaking Bowls and the Inscription of Identity and Memory

- 5. The Reuse, Recycling, and Displacement of Levantine Luxury Arts

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index