eBook - ePub

Cultural Evolution

How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Evolution

How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences

About this book

Charles Darwin changed the course of scientific thinking by showing how evolution accounts for the stunning diversity and biological complexity of life on earth. Recently, there has also been increased interest in the social sciences in how Darwinian theory can explain human culture.

Covering a wide range of topics, including fads, public policy, the spread of religion, and herd behavior in markets, Alex Mesoudi shows that human culture is itself an evolutionary process that exhibits the key Darwinian mechanisms of variation, competition, and inheritance. This cross-disciplinary volume focuses on the ways cultural phenomena can be studied scientifically—from theoretical modeling to lab experiments, archaeological fieldwork to ethnographic studies—and shows how apparently disparate methods can complement one another to the mutual benefit of the various social science disciplines. Along the way, the book reveals how new insights arise from looking at culture from an evolutionary angle. Cultural Evolution provides a thought-provoking argument that Darwinian evolutionary theory can both unify different branches of inquiry and enhance understanding of human behavior.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultural Evolution by Alex Mesoudi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780226520445, 9780226520438eBook ISBN

97802265204521 A Cultural Species

Humans are a cultural species. We acquire a multitude of beliefs, attitudes, preferences, knowledge, skills, customs, and norms from other members of our species culturally, through social learning processes such as imitation, teaching, and language. This culturally acquired information affects our behavior in quite fundamental ways. People who grow up in different societies exhibit measurably different ways of thinking and behaving because they acquire different cultural norms and beliefs from other members of their societies. Culturally transmitted technology, from stone tools to automobiles to the internet, and culturally transmitted political, economic, and social institutions have drastically changed our environments and our lives in a relatively short period of time. No other species on the planet exhibits such rapid and effective cultural change.

As a result, any explanation of human behavior that ignores culture, or treats it in an unsatisfactory manner, will almost certainly be incomplete. Yet a large number of social and behavioral scientists—many psychologists, economists, and political scientists, for example—either implicitly or explicitly downplay or ignore cultural influences on human behavior, instead focusing on the behavior and decisions of single individuals with little or no consideration of how that behavior and those decisions are affected by culturally acquired norms and beliefs. Other social scientists—many cultural anthropologists, archaeologists, sociologists, and historians, for example—do acknowledge the importance of culture, yet their methods and approaches often lack the scientific rigor and precision needed to satisfactorily explain how and why culture is the way that it is and how it affects behavior in the way that it does. Consequently, while the natural and physical sciences have made huge progress in the last century or so in explaining the hidden mysteries of life, matter, and the universe, the social sciences have failed to provide a unifying and productive theory of cultural change. The different branches of the social sciences remain fractionated, each speaking their own, often mutually unintelligible, languages and holding assumptions and theories that are mutually incompatible. Indeed, a good example of this mutual incompatibility concerns the very definition of “culture” itself, which varies greatly from discipline to discipline. It is necessary, then, to clearly specify the definition of “culture” that will be used in the rest of this book, before going on to demonstrate the extent to which culture shapes our behavior.

What Is Culture?

“Culture” is one of those concepts, like “life” or “energy,” that most people use in everyday speech without giving much thought to its precise meaning. In fact, people often use it in several different, but overlapping, senses. For example, it might be used to identify a specific group of people, usually within a single nation, such as “French culture” or “Japanese culture.” Or it might be used in the sense of “high culture,” such as literature, classical music, and fine art, as is the focus of many “culture” sections of Sunday newspapers. Or it might be used to describe a seemingly shared set of values or practices within a group or organization. For example, during the financial crisis that began in 2007, many commentators lamented the “culture of greed” that seemed to be prevalent within the banking industry, as it emerged that CEOs were still receiving huge bonuses even as their banks were being bailed out using public money.

When scientists use the term “culture,” they usually mean something broader, something that encompasses all three of the definitions above. Although literally hundreds of definitions of culture have been proposed across the social sciences over the years, the definition that I will adopt in the rest of this book is that culture is information that is acquired from other individuals via social transmission mechanisms such as imitation, teaching, or language.1 “Information” here is intended as a broad term to refer to what social scientists and lay people might call knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, norms, preferences, and skills, all of which may be acquired from other individuals via social transmission and consequently shared across social groups. Whereas genetic information is stored in sequences of DNA base pairs, culturally transmitted information is stored in the brain as patterns of neural connections (albeit in a way that neuroscientists are only beginning to understand), as well as in extrasomatic codes such as written language, binary computer code, and musical notation. And whereas genetic information is expressed as proteins and ultimately physical structures such as limbs and eyes, culturally acquired information is expressed in the form of behavior, speech, artifacts, and institutions.

This definition of culture encompasses in one way or another all of the colloquial uses of culture noted above. Culture includes the Japanese grammar and vocabulary, Japanese norms, and Japanese customs that a Japanese child acquires that contribute to maintaining the specific “Japanese culture.” The skill required to use chopsticks, for example, is stored in the brains of virtually all Japanese people, is acquired from other people via imitation or teaching, and is expressed behaviorally in the form of chopstick use. Cultural groups are not always the same as nation-states, though: there is substantial variation in the customs and values of people living in different regions of Japan, while Japanese customs such as chopstick use have diffused to many other nations. Culture also includes the literature, music, and art that make up “high culture,” although it is by no means limited to this. Celebrity gossip about the latest relationship problems of Hollywood movie stars is just as much a part of human culture as are the works of William Shakespeare. And culture includes those norms and practices that may have been transmitted from banker to banker via imitation or direct instruction that create and maintain selfish behavior within an organization.

According to this definition, culture is defined as information rather than behavior (in anthropological jargon, it is an ideational definition of culture). Restricting our definition of culture to information does not mean to say that culturally acquired information does not affect behavior. Of course it does, otherwise it would be a useless concept for explaining human behavior. However, as anthropologist Lee Cronk makes clear, it is important to distinguish between culture and behavior for two reasons.2 First, if behavior is the thing we are trying to explain, then including it in the definition of culture makes cultural explanations for behavior circular. A thing cannot explain itself, at least not in any useful sense. And second, there are other causes of behavior besides culture. In fact, this is a useful way of defining culture: by what it is not. First, as noted above, culture can be distinguished from information that we acquire genetically, from our biological parents, which is stored as DNA base pair sequences and expressed as proteins and, ultimately, as entire organisms. Second, culture can be distinguished from information that we acquire through individual learning, which describes the process of learning on our own with no influence from other individuals. While individually learned information, like culturally acquired information, is stored in the brain, it is not acquired from other individuals via cultural transmission. This distinction between genetically, culturally, and individually acquired information is important, because even if we observe variation between people and groups in some behavioral practice, we cannot automatically assume that the explanation of this behavioral variation is culture. Take variation in alcohol drinking, for example. Some variation in alcohol drinking is most likely cultural in origin, for example, resulting from the culturally transmitted norms prohibiting the drinking of alcohol found in religions such as Islam, or the more informal prodrinking norms found in certain social groups such as university fraternities and sororities. But some variation might be the result of individual learning, where a person independently decides to drink (or not to drink) alcohol because they like (or dislike) its taste or its effects. Other variation in alcohol drinking might be genetic. Indeed, certain genetic alleles have recently been found to increase a person’s risk of alcohol dependency such that people with these alleles have higher alcohol intake than people without these alleles. Many East Asians, on the other hand, lack a different genetic allele that would allow them to digest alcohol, potentially decreasing the frequency of alcohol drinking in that group.3

How Important Is Culture?

Given these alternative explanations for human behavioral variation, how can we be sure that culture really is important, compared to genes and individual learning? Here are three examples, one from political science, one from economics/cultural anthropology, and one from psychology, that illustrate the importance of culture in shaping our behavior.

Civic Duty: From Europe to America

It is often said that the United States is a nation of immigrants. Leaving aside the issue of the several million Native Americans who already lived on the continent, the early European settlers of North America did indeed come from various countries, including Britain, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. As anyone who has traveled across Europe will be aware, while the inhabitants of each of these countries are broadly similar in their beliefs and attitudes (at least compared to, say, Japan or India), there are also significant differences between European countries. One such difference relates to values and attitudes concerning civic duty. These include various traits that can be considered beneficial to a liberal democratic society, such as the tendencies to donate to charity and conduct voluntary work, to vote in elections, to organize local pressure groups and labor unions, to regularly read newspapers (and thus be able to make informed democratic decisions), and to support social equality and representation for minorities. Some countries, such as Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, are high in average civic duty. Their inhabitants willingly donate to charity, vote, volunteer, and so on. Other countries, such as Italy and Spain, rank somewhat lower in average civic duty. Their inhabitants are less likely to, among other things, donate to charity, vote, and volunteer.

To political scientists Tom Rice and Jan Feldman, this cultural variation in civic duty presented a natural experiment that could test to what extent cultural differences persist over time.4 Rice and Feldman reasoned that if values related to civic duty are faithfully passed via cultural transmission from parent to child and teacher to pupil, down the generations, then perhaps the civic duty of contemporary Americans could be predicted by the specific European country that their settler ancestors came from. So Rice and Feldman calculated the civic duty for Americans of various European ancestries. They did this using the answers to such questions as “Do you regularly read a news paper?,” “Did you vote in the last presidential election?,” and “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?,” and whether they agreed with such statements as “Most public officials are not really interested in the problems of the average person” and “Women should take care of running their homes and leave running the country up to men.”

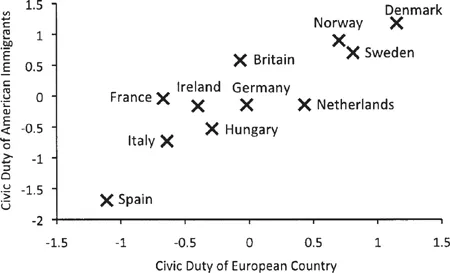

Rice and Feldman’s results were just as they predicted. Americans who claim to be descended from settlers from European countries that have high civic duty, such as Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, themselves have relatively high civic duty. Americans who claim to be descended from European countries that have low civic duty, such as Italy and Spain, have relatively low civic duty. This can be seen in figure 1.1. Rice and Feldman’s explanation for this match is that values related to civic duty, such as beliefs that voting or donating to charity are important and desirable things to do, have been culturally transmitted by imitation or teaching from parent to child or teacher to pupil over the several successive generations from original European settlers to present-day Americans. This would have occurred despite extensive interaction with other Americans of different descent, despite a declaration of independence and a civil war, and despite differences between Europe and the United States in geography and ecology. And a subsequent study by Tom Rice and Marshall Arnett showed that values related to civic duty can have important consequences.5 They found that the average civic duty measured in different states at several points during US history significantly predict later socioeconomic development. For example, states that scored highly in civic duty in the 1930s were found to have relatively higher levels of personal income and education in the 1990s than states that scored low in civic duty in the 1930s. The reverse was not true: socioeconomic performance in the 1930s did not predict civic duty in the 1990s. So civic duty seems to be responsible for later socioeconomic development. The way in which it did this is not entirely clear, but we might imagine that states in which the residents more strongly value representative democracy elect more effective and honest public representatives, or perhaps rich residents of such states give more to charity, thus reducing inequality and raising average income. In any case, Rice and colleagues’ work illustrates how people’s cultural values can persist over several generations and significantly shape people’s behavior and the society in which they live.

FIGURE 1.1 The correlation between civic duty of European populations and the civic duty of contemporary Americans who claim to be descended from those European populations. Values are composite z-scores from various measures of civic duty. Data from Rice and Feldman 1997.

Is Fairness Universal?

Rice and colleagues’ studies are intriguing, but limited somewhat because they rely on self-reported measures of civic duty. Someone who says that it is important to vote or donate to charity is not necessarily someone who actually votes or donates to charity. An alternative way of exploring cultural variation is by directly measuring people’s behavior in a controlled experimental setup.

One aspect of civic duty is fairness, and its flipside, selfishness. People high in civic duty tend to value fairness in personal interactions (e.g., business dealings), with each party getting a fair deal, while people low in civic duty tend to eschew the ideal of fairness and attempt to selfishly maximize their own personal gain at the expense of the other person. One way that experimental economists have tested people’s sense of fairness/selfishness is known as the ultimatum game. The ultimatum game is played by two players, a proposer and a responder. The proposer must divide up a sum of money, say $100, into two portions, one that the proposer can keep and the other that is given to the responder to keep. For example, the proposer might split the $100 equally into two $50 portions (a fair offer), they might offer $20 and keep $80 for themselves (a selfish offer), or they might offer $80 and keep $20 (a generous offer). The responder can then decide whether to accept this offer, in which case they both get the amounts specified by the proposer, or reject the offer, in which case neither the proposer nor the responder get anything. Typically, the game is played just once and both players are anonymous, in order to avoid complications like pacts, promises, and reputation. The amount of money to be divided is also fairly substantial in order to motivate the players to give serious responses.

In a typical sample of US college students, the most common offer made by proposers is 50 percent, a fair and equal split. And responders react in a way that suggests they also have a sense of fairness: any offer less than 20 percent is rejected half the time.6 It seems that responders have a sense of fairness, rejecting offers that they perceive as being unfair. Proposers, knowing this, make fair offers. So these experimental findings show that US college students are not entirely selfish and, consistent with the existence of civic duty, exhibit some degree of charity to others and a sense of fairness.7

Just as civic duty varies across countries and states, so too fairness responses in the ultimatum game vary across different societies. A team of cultural anthropologists led by Joseph Henrich of the University of British Columbia ran ultimatum game experiments in fifteen small-scale societies in twelve countries across the world.8 These societies had diverse ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. A Cultural Species

- 2. Cultural Evolution

- 3. Cultural Microevolution

- 4. Cultural Macroevolution I: Archaeology and Anthropology

- 5. Cultural Macroevolution II: Language and History

- 6. Evolutionary Experiments: Cultural Evolution in the Lab

- 7. Evolutionary Ethnography: Cultural Evolution in the Field

- 8. Evolutionary Economics: Cultural Evolution in the Marketplace

- 9. Culture in Nonhuman Species

- 10. Toward an Evolutionary Synthesis for the Social Sciences

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index