- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Decision Between Us combines an inventive reading of Jean-Luc Nancy with queer theoretical concerns to argue that while scenes of intimacy are spaces of sharing, they are also spaces of separation. John Paul Ricco shows that this tension informs our efforts to coexist ethically and politically, an experience of sharing and separation that informs any decision. Using this incongruous relation of intimate separation, Ricco goes on to propose that "decision" is as much an aesthetic as it is an ethical construct, and one that is always defined in terms of our relations to loss, absence, departure, and death.

Laying out this theory of "unbecoming community" in modern and contemporary art, literature, and philosophy, and calling our attention to such things as blank sheets of paper, images of unmade beds, and the spaces around bodies, The Decision Between Us opens in 1953, when Robert Rauschenberg famously erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning, and Roland Barthes published Writing Degree Zero, then moves to 1980 and the "neutral mourning" of Barthes' Camera Lucida, and ends in the early 1990s with installations by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Offering surprising new considerations of these and other seminal works of art and theory by Jean Genet, Marguerite Duras, and Catherine Breillat, The Decision Between Us is a highly original and unusually imaginative exploration of the spaces between us, arousing and evoking an infinite and profound sense of sharing in scenes of passionate, erotic pleasure as well as deep loss and mourning.

Laying out this theory of "unbecoming community" in modern and contemporary art, literature, and philosophy, and calling our attention to such things as blank sheets of paper, images of unmade beds, and the spaces around bodies, The Decision Between Us opens in 1953, when Robert Rauschenberg famously erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning, and Roland Barthes published Writing Degree Zero, then moves to 1980 and the "neutral mourning" of Barthes' Camera Lucida, and ends in the early 1990s with installations by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Offering surprising new considerations of these and other seminal works of art and theory by Jean Genet, Marguerite Duras, and Catherine Breillat, The Decision Between Us is a highly original and unusually imaginative exploration of the spaces between us, arousing and evoking an infinite and profound sense of sharing in scenes of passionate, erotic pleasure as well as deep loss and mourning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Decision Between Us by John Paul Ricco in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Name No One

1: Name No One Man

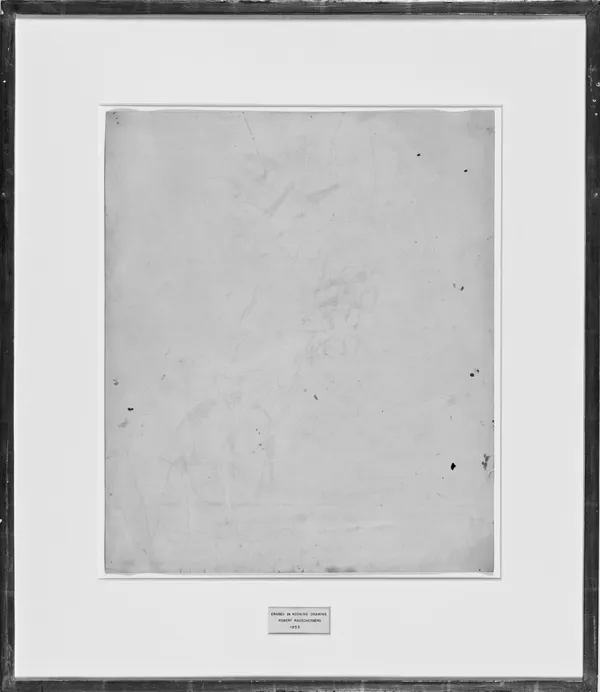

Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) counts as the most distinct image in twentieth-century art, and perhaps in the entire history of art (fig. 1).

Given that the work consists of a single sheet of drawing paper (matted, labeled, and framed) and that this sheet of paper appears to be almost completely absent of any visible marks, thereby granting it a legibility limited to the ordinary and unremarkable, it would seem that the claim that I have just made about the work is insupportable. Based upon the evidence, it can easily be argued that the sheet of paper doesn’t bear anything remotely resembling an image, and that in its sheer ordinariness, the semantic limits of any meaningful sense of distinction are pushed to the breaking point. Nonetheless, in what follows I will argue that through its signature deployment of erasure, its refusal of the evidentiary, and its partaking of archival logics, the Erased de Kooning presents us with a whole series of questions about the act of counting, about what and who counts, about the accounted and the unaccounted for, and about what it might mean “to occupy without counting.”1 Through a praxis of withdrawal and retreat that is guided by the palindromic imperative to name no one man, the Erased de Kooning Drawing is the exposition of an image of shared sociality, and thereby a thinking of the political that has never been more crucial and is the mark of the work’s political in addition to ethical and art historical distinction.

What follows, then, is just as much an issue of legibility as it is of visibility, and more precisely, in the form of the aporia of reading what remains unwritten in writing, and of seeing what remains unforeseeable in that which is seen. These are political questions, in that, as Jacques Rancière affirms, politics is always a policing of visibility and invisibility, and so to make the political happen as something other than a sanctioned form of politics, it is necessary to break through this dialectical trap by a movement toward that which is unforeseeable and imperceptible, and that which exists outside the boundaries and mandates of compulsory and confessional visibility and identification, and violent visual oblivion or disappearance. The fact that paper has been one of the principal material surfaces, objects, and spaces for these contestations over who and what counts is of great consequence for us here, in our consideration of Rauschenberg’s drawing in terms of its political-aesthetic and ethical import.

Figure 1. Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953; traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame; 25-1/4 in. × 21-3/4 in. × 1/2 in. (64.14 cm × 55.25 cm × 1.27 cm); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase through a gift of Phyllis Wattis. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Rauschenberg and the Scene of Erasing

In this chapter, we turn to various scenes of writing and drawing, beginning with Jacques Derrida’s 1966 lecture “Freud and the Scene of Writing.” In it, Derrida addresses the metaphors of writing in the historical development of Freud’s theories of perception, the unconscious, and memory, all of which might be said to culminate in Freud’s 1925 paper “A Note upon the Mystic Writing Pad.” However, from as early as 1895, in his book Project for a Scientific Psychology, Freud had been seeking a technological analogy that would serve as a conceptual model for the structure of the mental apparatus, the psyche. Specifically, he was seeking some sort of apparatus of writing that in its ability to illustrate this structure and its operation would need to satisfy a double requirement: it would need to possess “a potential for indefinite preservation and an unlimited capacity for reception of the inscriptions that have been made on it.”2 A single sheet of paper will not qualify, since as Freud writes, “The receptive capacity of the writing-surface is soon exhausted”—filled up, and hence with no more room for any additional legible marks or traces to be made on it. Alternatively and for opposite reasons, a chalkboard also will not qualify, since while it retains its infinite capacity to receive traces and marks, it does so through the necessary process of wiping away some or all of those that had been previously made, hence negating its potential to preserve.

Confronted with this relation between the properties of writing and erasing to be one of mutual exclusivity, Freud will only find a resolution to his dilemma in the Mystic Writing Pad (Wunderblock), a device—in fact, little more than a child’s toy (as Derrida reminds us)—that came onto the market not long before Freud’s writing, and that many of us today are still familiar with from our own childhoods. It is one of those three-layered tablets, consisting of a translucent celluloid sheet below which is attached along one edge a sheet of wax paper, both of which are then attached along a single edge to a thin wax slab. Only a stylus is necessary to write or draw on its surface; no ink or graphite is required. By lifting the first and second sheets up and away from the wax slab, whatever marks have been registered on the pad are effectively erased, clearing the surface for more marks and traces to be made upon it. Now, this would seem to be as much of a disqualifying feature as the simple sheet of paper or the chalkboard, except that, as Freud points out, if one looks at the wax slab under certain lighting conditions, one can perceive traces—in the form of impressions in the waxy surface—of the marks that had previously been made with the stylus. Thereby the wax slab, and by extension the Mystic Writing Pad, functions as an apparatus of infinite receptivity and preservation of traces. As Freud satisfyingly concludes:

Thus the Pad provides not only a receptive surface that can be used over and over again, like a slate, but also permanent traces of what has been written, like an ordinary paper pad: it solves the problem of combining the two functions by dividing them between two separate but interrelated component parts or systems.3

While Freud finds in the Mystic Writing Pad an analogy for the relation in the mental apparatus between unlimited reception and indefinite preservation, the quotation above makes it clear that this is based upon his understanding of the apparatus (psyche and child’s toy at once) as one that maintains a structural division between this reception and preservation, thereby maintaining these as “two separate but interrelated component parts or systems.” But of course things are a bit more complicated and, shall we say, entangled, in that what enables this writing apparatus to work in the way that Freud wants it to work requires it to be entirely dependent upon the process of erasure, and in such a way that, as we shall see, it becomes difficult to construe the relation between writing and erasing as antonymic, and the division and maintenance of their separation to be ever truly possible. In the last sentence of his “Note,” Freud hints at this, when he imagines what would seem to be an impossible two-handed writing-erasing:

If we imagine one hand writing upon the surface of the Mystic Writing-Pad while another periodically raises its covering-sheet from the wax slab, we shall have a concrete representation of the way in which I tried to picture the functioning of the perceptual apparatus of the mind.4

Toward the end of his essay, Derrida states that in the “Note,” Freud “performed for us the scene of writing. [Then immediately goes on to say] But we must think this scene in other terms than those of individual or collective psychology, or even of anthropology. It must be thought in the horizon of the scene/stage of the world, as the history of that scene/stage.”5 Note that Derrida does not say “the history of the horizon of the scene/stage,” but instead “the history of that scene/stage.” The difference may appear to be so slight as not to warrant comment (or notice), and yet what lies in this seemingly infinitesimal gap is nothing less than the difference between the sense that writing-erasing is the stage of history and the scene of the world as infinitely finite—the retracing of its retreating—and of writing (and erasing if it can even be adequately recognized here) as nothing more than the representation of the world as a finite relation to the infinite. Which is to say, as beholden to some metaphysical force, of which writing would be little more than a predetermined exercise of transcription rather than the undetermined praxis of mise-en-scène—the latter of which is the space of decision, including the very decision of existence and world, together. Following quite closely the trail that Derrida had opened all those many years ago, we can say that “what we are describing here as the labor of writing [drawing] erases the transcendental distinction between the origin of the world and Being-in-the-world. Erases it while producing it.”6 Erasure is the source of creation, including the “creation of the world,” so to speak.

This is, then, a path-breaking force and space at once, that in its breaching makes any outline, partition, or limit (including any sense of horizon) neither permeable/transparent nor impermeable/opaque. For Freud it is Bahnung; for Derrida, frayage; and for us, a retreating retracing—all of which semantically resonate as the breaching and fraying of every edge that would otherwise coalesce as the confinement of an outline, partition, or limit (including a horizon) and render the scene a tableau of representation. Which is to say that the labor or praxis at issue here cannot be spoken about in the conventional terms of creation or destruction, but of distinction, in which fraying’s frayed edge is the force and space of distinction. I shall return to this.

At the same time, while we will want to preserve a degree of the conceptual open-endedness and indetermination of content that is found in Freud’s statement (from the 1895 book) that “in what path-breaking [sic] consists remains undetermined,” we will nonetheless assert that when Rauschenberg performs for us the scene of drawing/erasing, it is in the mode of neither representation nor transcription, and therefore calls for a method of analysis, if not in fact a discipline, other than that of interpretation. For in the Erased de Kooning Drawing, we would not say that Rauschenberg has represented erasing, or drawing, or his authorial presence or de Kooning’s artistic absence—propositions all of which make little to no sense here.

And while we now know that Derrida was quite insistent about the need to think the scene of writing that Freud performs for us as the scene/stage of the world, as readers of Freud we cannot help but hear in that phrasing a reference to the one most commonly associated with Freudian psychoanalysis—namely, the primal scene. In fact, in Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety Freud draws exactly this analogy between writing, spatial movement, and sexual acts when he writes:

As soon as writing, which entails making liquid flow out of a tube onto a piece of white paper, assumes the significance of copulation, or as soon as walking becomes a symbolic substitute for treading upon the body of mother earth, both writing and walking are stopped because they represent the performance of a forbidden sexual act.7

Following upon this, and confronted with the Erased de Kooning, we might want to ask what kind of “performance of a forbidden sexual act” is enacted when the scene of writing (or drawing) becomes the scene of erasure; and further, whether running if not walking might not be (at least partially) a more accurate way of describing the treading upon the body of another artist as seems to have taken place here.

In what follows, I try to think the sociality and spatiality of other scenes and surfaces that imply neither the masturbatory nor the incestuous acts suggested by Freud, but some other equally forbidden alliance, and a path-breaking all its own. One that I will argue is the opening onto, and exposure to, a sociality of shared-separation, a distinctly incalculable shared sociality that is, at times, also a traitorous collaboration. Neither a psychological, anthropological, or perhaps even political community as the being or becoming of a collective totality, but rather the sociality of what we might name the unbecoming community.

I shall begin, then, with two divergent statements, each in response to work made by the artist Robert Rauschenberg in the early 1950s. The first is that of an exasperated Barnett Newman, who, upon seeing Rauschenberg’s unpainted canvas paintings, exclaimed: “Humph! Thinks it’s easy. The point is to do it with paint.” The second is part of the epigraph to John Cage’s essay about his close friend and collaborator Rauschenberg, addressed to an anonymous addressee, and intended to clarify an issue of historical chronology: “To Whom It May Concern: The white paintings came first, my silent piece came later—J.C.”8 The White Paintings referred to by Cage are a series of works that Rauschenberg executed in 1951, using nothing more than ordinary white house paint and canvas, and of course “my silent piece” refers to Cage’s perhaps most well-known and often discussed composition, 4′33″ (1952)—four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. Clearly, Cage and Rauschenberg understood the potential of an artistic practice that effectively, and yet through the simplest of methods, could fundamentally alter conceptions of painting and musical composition, in which, for instance, an unpainted canvas and a specific duration of silence, which are none other than that unpainted canvas and that specific period of silence, are the persistence of existing as painting and as musical composition. In the White Paintings, 4′33″, and Erased de Kooning Drawing, the work of art exposes and is exposed to the potential to be and to not-be at once, an exposure that is what William Haver refers to as “art’s work.”9 Art’s work runs the risk that is the full force of potentiality, such that in the wake of the White Paintings it will be difficult any longer to ignore the retreat of image that is the condition that enables any image to be registered, just as Cage’s piece performs silence as the outside that insidiously dwells within all sound and enables the latter to be heard.

Erasure

Erasure turns drawing, turns a—and perhaps any—drawing around. It turns on drawing by betraying drawing, and hence within the realm of drawing, erasing cannot be trusted or counted on. As we have said, the incalculable, that which cannot be counted, is a predicament that we may not be able to, nor want to, overcome. The questions of calculation, of how many count and even more so, of how one counts and of who counts (both as counter and counted), all of these, it appears, must remain only partially answerable. For when it is a matter of drawing, does erasing still count, even if, as I have already suggested, it cannot be counted on—that is, trusted? When it comes to drawing, what can one count on?

In the case of Willem de Kooning, it seems justified to say that not only did he continue in the artistic tradition of preliminary sketches, drawings, and studies, but that he was a consummate draftsman—not simply one who drew, but who masterfully exhibited the classical qualities of disegno, that artistic achievement enshrined by Giorgio Vasari and academically maintained for centuries. Presumably this played some part in Rauschenberg’s decision to approach this well-known older artist and request one of his drawings for the purposes of erasing it. Evidently, and not too surprisingly, de Kooning initially balked at the idea, but eventually relented, and decided to give the young artist not simply any drawing, but one that was thoroughly and heavily covered with pencil, crayon, charcoal, and so forth.

Yet, as Leo Steinberg suggested in one of his last lectures on Rauschenberg, there may be another reason why he, Rauschenberg, was drawn to de Kooning, one that has less to do with de Kooning’s drawing practice than it has to do with his, de Kooning’s, own erasing, or more accurately the fact that, in Steinberg’s words, “De Kooning was the one who belabored his drawings with an eraser.”10 One might go so far as to argue that de Kooning’s expert draftsmanship was predicated upon his approach or exposure to drawing’s potentiality, including its potential to not-be—namely, its exposure to the force of erasure. The relation between drawing and erasing, then, is not oppositional as much as it is an infinite folding of the two ac...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgment

- Introduction

- Part I. Name No One

- Part II. Naked

- Part III. Neutral and Unbecoming

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Gallery