- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Teenage life is tough. You're at the mercy of parents, teachers, and siblings, all of whom insist on continuing to treat you like a kid and refuse to leave you alone. So what do you do when it all gets to be too much? You retreat to your room (and maybe slam the door).

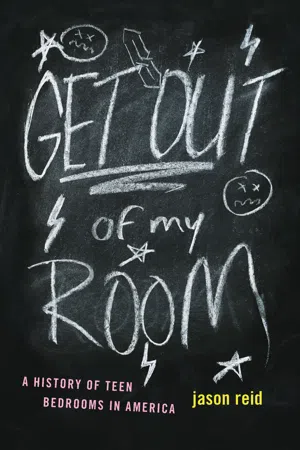

Even in our era of Snapchat and hoverboards, bedrooms remain a key part of teenage life, one of the only areas where a teen can exert control and find some privacy. And while these separate bedrooms only became commonplace after World War II, the idea of the teen bedroom has been around for a long time. With Get Out of My Room!, Jason Reid digs into the deep historical roots of the teen bedroom and its surprising cultural power. He starts in the first half of the nineteenth century, when urban-dwelling middle-class families began to consider offering teens their own spaces in the home, and he traces that concept through subsequent decades, as social, economic, cultural, and demographic changes caused it to become more widespread. Along the way, Reid shows us how the teen bedroom, with its stuffed animals, movie posters, AM radios, and other trappings of youthful identity, reflected the growing involvement of young people in American popular culture, and also how teens and parents, in the shadow of ongoing social changes, continually negotiated the boundaries of this intensely personal space.

Richly detailed and full of surprising stories and insights, Get Out of My Room! is sure to offer insight and entertainment to anyone with wistful memories of their teenage years. (But little brothers should definitely keep out.)

Even in our era of Snapchat and hoverboards, bedrooms remain a key part of teenage life, one of the only areas where a teen can exert control and find some privacy. And while these separate bedrooms only became commonplace after World War II, the idea of the teen bedroom has been around for a long time. With Get Out of My Room!, Jason Reid digs into the deep historical roots of the teen bedroom and its surprising cultural power. He starts in the first half of the nineteenth century, when urban-dwelling middle-class families began to consider offering teens their own spaces in the home, and he traces that concept through subsequent decades, as social, economic, cultural, and demographic changes caused it to become more widespread. Along the way, Reid shows us how the teen bedroom, with its stuffed animals, movie posters, AM radios, and other trappings of youthful identity, reflected the growing involvement of young people in American popular culture, and also how teens and parents, in the shadow of ongoing social changes, continually negotiated the boundaries of this intensely personal space.

Richly detailed and full of surprising stories and insights, Get Out of My Room! is sure to offer insight and entertainment to anyone with wistful memories of their teenage years. (But little brothers should definitely keep out.)

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Get Out of My Room! by Jason Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

A Little Wholesome Neglect

No man prefers to sleep two in a bed. In fact, you would a good deal rather not sleep with your own brother. I don’t know how it is, but people like to be private when they are sleeping.

HERMAN MELVILLE, MOBY DICK (1851)

In 1868 Anna Stanton, a thirty-six-year-old woman from Indiana, took on a teaching assignment four miles outside of Le Mars, Iowa, a sparsely settled prairie town that was in dire need of qualified educators. As was customary at the time, a portion of Stanton’s $2.50 weekly salary went to a family who offered her room and board for the length of her teaching assignment. Though Stanton was thankful for her hosts’ generosity, the house she stayed in offered little in the way of privacy. “Size of house 16 x 18, all one room,” she wrote in her autobiography. “The single brother has his bed on his side of the house, the married brother on his side. For me a cot was made and it was so near the cookstove I could put my hand on it. It took a great deal of maneuvering to get in and out of bed.” Stanton was similarly troubled by the fact that her hosts often took in travelers. “On one occasion,” she explained, “a family stopped, spread their bedding on the floor for six or eight, did their cooking on the stove, and next morning were up early, ate their breakfast and started on. I did not hear a word of complaint from either side.” For Stanton, who had presided over a room of her own as a child, the cramped living arrangements produced a certain amount of discomfort and unease. “They were good, pure minded people and I got along very well,” she noted, “but to those used to their own private room it was a little hard to reconcile.”1

Though one might expect frontier homes to be somewhat lacking in terms of personal privacy, housing in more established parts of the country was similarly cramped. Many urban-dwelling Americans—particularly those from large and/or poor families—shared beds and bedrooms with siblings, parents, and even total strangers. John Gough, a British-born temperance advocate who came to America as a ten-year-old, recalled sharing a bed with a gravely ill man after moving in to a New York City boardinghouse in 1831. “To my surprise,” he recalled in his autobiography, “I found, when the hour of rest approached, that I was to share a bed with an Irishman, who was lying very sick of a fever and ague. The poor fellow told me his little history; and I experienced the truth of the saying, that ‘Poverty makes us acquainted with strange bed-fellows.’” These stories continued to flourish after the Civil War, when America’s urban centers grew at an unprecedented rate. Famed novelist Upton Sinclair, for instance, recalled sharing a bedroom with his parents in Baltimore during the 1870s and 1880s. “We never had but one room at a time,” Sinclair wrote in his memoirs, “and I slept on a sofa or crossways at the foot of my parents’ bed.” Though Sinclair was bothered by the fact that most of the dwellings he and his parents occupied were run down and teeming with bedbugs, he admitted that sharing a bedroom with his parents caused him “no discomfort,” all things considered.2

For many nineteenth-century Americans, then, home life was often characterized by a lack of privacy, by a measure of proximity among blood relatives, acquaintances, and strangers that contemporary Americans might find off-putting. Some Americans, however, made a concerted attempt to buck this trend, as a select group of middle-class, urban-dwelling families ushered in a privacy-oriented approach to housing that shaped teen bedroom culture in a wide-ranging manner. As the teen bedroom was just one space among many expected to act as a refuge from both the outside world and other family members, its earliest expressions were part of a larger process in which, to quote two prominent twentieth-century architects, the “forced togetherness” of early American homes was replaced by an approach emphasizing privacy and “voluntary communality.” Though one would be hard pressed to argue that the nineteenth century witnessed the creation of a fully formed teen bedroom culture, the bedrooms Americans are familiar with nowadays certainly had their origins during this period, offering youngsters a space within the home that stressed, among other things, character building, intellectual growth, spiritual awareness, and personal responsibility.3

Socioeconomic Change during the Antebellum Era

In order to best understand the emergence of teen bedroom culture, one must examine the extent to which economic changes during the early nineteenth century altered both basic family structures and the layout of the average middle-class home. The economy during the antebellum era became less agrarian in nature as commercial and industrial capitalism began to transform American society in a far-reaching manner. The urban middle-class families who benefited most from these socioeconomic transformations tended to differentiate themselves from their rural/working-class counterparts by placing much greater emphasis on personal privacy in the home. Dubbed the “isolated household” by historian Dolores Hayden, this new approach to housing became a prominent feature of middle-class identity during the Victorian era, acting as a bellwether for the health and success of the family as a whole. A successful family, after all, was expected to live in a detached or semidetached home with enough square footage to accommodate the privacy demands of parents and children alike, while cramped tenements, boardinghouses, and other dwellings associated with the poor were to be avoided at all costs. The isolated household was considered superior because it created a buffer against the outside world, offering its occupants a means of nourishing their individuality in, as architectural historian Clifford Clark describes them, a host of “separate but interdependent spaces.” For affluent Americans who could afford to embrace this ideal, togetherness was to be a matter of choice rather than an imposition.4

Of course, the privacy demands associated with the isolated household could not have been met without a steep decline in family size. In 1800 the typical American mother could expect to give birth to an average of 7.0 children in her lifetime; by 1900, however, that number had dipped to 3.6. In a span of a hundred years, then, the birthrate was essentially cut in half, meaning that parents often had fewer children to consider when determining basic living arrangements. Lower birthrates became the norm among middle-class families in particular, due to the decline of the family economy and the transformation of children into consumers rather than producers of wealth. The costs of raising children, in short, began to far outweigh their economic benefits. Although rural and working-class families often found themselves at odds with this particular mode of living due to their continued reliance on child labor, the growing prevalence of small, tight-knit nuclear families played a significant role in bringing about the emergence of the autonomous teen bedroom because the custom of combining siblings in beds and bedrooms became less necessary as family size shrank. The decision to provide children with rooms of their own was a matter of simple arithmetic, as a family of four or five was much more capable of living up to this ideal than a family of eight or nine.5

As with nurseries, playrooms, and other child-oriented spaces during the Victorian era, the teen bedroom was shaped by Americans’ ever-changing views on childhood and child-rearing. The privacy offered by separate sleeping quarters was thought to have a beneficial effect on the basic character of youth—a notion that first found expression in the early nineteenth century with the emergence of sheltered childhood, an approach to child-rearing that used segregation within the home as a means of creating firm distinctions between the lived experiences of adults and children. Characterized by a particularly romantic view of children, the sheltered childhood ideal emphasized educational goals, leisure, and the innate goodness of children. Whereas earlier generations of parents tended to regard children as miniature adults who were expected to work and form a family at a relatively young age, this new approach prolonged the period of childish dependency by limiting a child’s interaction with the adult world. Indeed, by the latter decades of the nineteenth century, the sheltered childhood ideal was so prevalent among affluent families that it was often used as a centerpiece in the fight against child labor. The average middle-class child, to adopt the parlance of sociologist Viviana Zelizer, was expected to be “economically useless” yet “emotionally priceless,” a beloved creature with distinct needs and interests whom parents were obliged to protect from some of the less palatable aspects of the adult world.6

The sheltered childhood ideal complemented the emergence of the isolated household in several ways. For starters, both concepts were premised on the idea that a certain amount of privacy was beneficial to one’s health and well-being. The inward-looking nuclear family, for example, was often regarded as the best means of shielding family members from the chaos and uncertainty of the outside world, with the home itself acting as a physical embodiment of the average family’s attempts to create clearly delineated boundaries between the private and public spheres. The sheltered childhood ideal, meanwhile, projected these distinctions into the realm of child-rearing. The decision to prolong the educational process and keep children at home for a longer period of time was based on the idea—popularized by John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau—that children were cheerful innocents who needed to be kept apart from the adult world, lest it corrupt their character or dull their spirit. This growing emphasis on generational separation would have a profound effect on the emergence of teen bedroom culture during the antebellum era. For instance, the desire to accommodate privacy demands within the home helped establish an environment in which the teen bedroom, as both an idea and a concrete entity, could flourish. Indeed, the early teen bedroom should be seen as the isolated household in microcosm, a means of reinforcing the uniqueness of children—and securing some much-needed privacy for parents—by, in effect, separating the generations for extended periods of time.7

The separate bedroom ideal first emerged during the early 1800s, proving somewhat popular among smaller, affluent families from the towns and cities of the Northeast. That the first instances of teen bedroom culture should emerge in New York or Massachusetts rather than South Carolina or Mississippi is not particularly surprising. Economically speaking, the northern states were simply better suited to accommodate these types of living arrangements. The southern economy was largely agrarian in nature and had not yet produced a powerful urban bourgeoisie that could sustain these types of living arrangements; its economy and culture had not yet been commandeered by the very people who tended to embrace the idea of privatized homes and separate bedrooms for children. The Northeast was also better suited to experiment with privacy-oriented living arrangements due to the simple fact that the educational options available to children there were much more extensive than in the South. Between 1838 and 1853 every northern state established a common school system, thus ensuring that children had access to schooling that was free of charge and (theoretically) nonsectarian. By contrast, the states that would eventually rally around the Confederate flag did not establish common school systems of their own until long after the Civil War had drawn to a close. This is important to note because teen bedrooms, as we will see below, were often defined by the extent to which they encouraged scholarly excellence and intellectual growth.8

Climate also played an important role in nurturing the growth of teen bedroom culture in the northern states during the early 1800s. Unlike their fellow countrymen south of the Mason-Dixon line, residents of northern states were often, as Henry Adams would have it, victims of “winter confinement” for months at a time—housebound creatures who endured the cold season knowing that there would be no respite from “daily life in winter gloom.” Under these circumstances, young and old alike could be forgiven for placing far greater attention to the various rooms they occupied within the home than, say, their peers in warmer climes. Every room in the house took on greater significance during the winter, especially spaces that were meant to accommodate the boundless energy of youth.9

Nonetheless, much of the prescriptive literature that was directed at middle-class families offers us mixed messages insofar as the “own room” concept is concerned. Very few commentators denounced the separate bedroom ideal, but one can’t help but notice that these types of living arrangements inspired a certain amount of ambivalence among the chattering classes. Some experts, for instance, were satisfied with merely separating parents and children during hours of rest. In 1819 educator William Mavor claimed that “it is esteemed unwholesome for children to sleep with old persons,” adding that “even if two persons of any age sleep together, the bed should be large.” This type of advice suggests that providing children with rooms of their own wasn’t an especially pressing issue during this time. Experts like Mavor may have taken issue with shared beds and bedrooms, but the purported dangers of these arrangements were not pronounced enough to recommend radical change. Indeed, it is telling to note that the most vocal supporters of the separate bedroom ideal tended to be builders who stood to benefit economically from these types of arrangements and middle-class housing reformers, many of whom were active participants in the housing industry.10

One of the most widely read reformers during the antebellum era was O. S. Fowler, an architect whose appreciation for separate bedrooms set him apart from many of his peers. In 1854 he claimed that separate suites could help “promote the development of children” by preventing the transmission of illness—“imbibing anything wrong from other children”—and ensuring that children avoid having “their slumbers disturbed by a restless bed-fellow” or a talkative roommate. Fowler similarly argued that separate bedrooms complemented a host of important middle-class values, including self-reliance, personal responsibility, and an appreciation for private property:

Where two or three children occupy the same room, neither feel their personal responsibility to keep it in order, and hence grow up habituated to slatternly disorder, whereas, if each had a room “all alone to themselves,” they would be emulous to keep it in perfect order, would feel personally responsible for its appearance, would feel ashamed of its disarrangement, would often find themselves alone for writing or meditation, but especially will feel a perfect satisfaction of the home element.

Conservative ideas on domesticity also informed Fowler’s advice, as he claimed that separate bedrooms could help young girls “cultivate the housekeeping arts.” This was to be accomplished by allowing girls to invite their parents up to their rooms in order to sip tea and “taste her cakes and dainties.” Ultimately, Fowler’s arguments were based on the notion that separate rooms for children would “contribute immeasurably” to their love of home. “Without it,” he added, “it is only their father’s home, not theirs. . . . By giving them their own apartment, they themselves become personally identified with it, and hence love to adorn and perfect all parts.”11

Though Fowler’s ideas were not particularly controversial, it would be a mistake to assume that they were broadly accepted within American culture during the antebellum era. It is striking to note, for instance, that Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most popular middle-class magazine of the time, had nothing to say about providing children with rooms of their own, despite offering its readers reams of advice on related aspects of family living. In fact, a case can be made that the “own room” concept failed to take off because communal living arrangements continued to be of value to rich and poor alike. On a practical level, shared beds and bedrooms were useful in colder parts of the country because they kept family members warm in an age before central heating. Perhaps more importantly, shared bedrooms also provided parents with a practical means of keeping an eye on children when traditional surveillance methods were not always effective. In 1831 Lydia Maria Child, an abolitionist and women’s rights activist, claimed that young girls should share a room with a “well-principled, amiable elder sister,” a “safe and interesting companion” who might act as a “great safeguard to a girl’s purity of thought and propriety of behavior.” If Child is to be believed, older children were useful in these types of situations because they could act as parental surrogates, ersatz authority figures who ensured that nightly prayers were performed while preventing late-night reading, acts of self-love, and other immoral behavior. Even if an older child desired a room of his or her own, he or she may have been prevented from doing so due to parental demands to stand watch over younger siblings whenever parents were unable to do it themselves.12

Of course, many families during the early nineteenth century were also reluctant to abandon shared bedrooms because they simply enjoyed the companionship they afforded. Benjamin Hallowell, a Quaker boy who was born in Pennsylvania in 1799, felt that sharing a bedroom with his ailing grandfather was a comforting experience, noting that he “always felt safe in his presence.” Sleeping alone, by contrast, was seen by some Americans as a source of alienation and, at times, terror. Samuel Goodrich found this out firsthand in 1811, when he became an apprentice at a dry goods store in Hartford, Connecticut, shortly after his eighteenth birthday. Wrenched from his family and crippled by religious angst, Samuel “slept in an upper room of a large block of brick buildings, without another human being in them.” The prospect of sleeping alone terrified Samuel. “Never have I known the ni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Little Wholesome Neglect

- 2 A Site of Developmental Significance

- 3 Give a Room a Little Personality—Yours!

- 4 The Sign Reads ‘Keep Out’

- 5 Rooms to a Teen’s Tastes

- 6 Go to Your Multimedia Center!

- 7 Danger!

- 8 Just Like Brian Wilson Did . . .

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index