- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

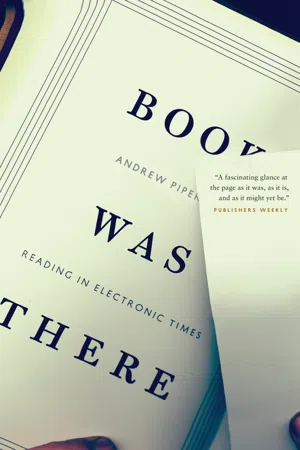

Andrew Piper grew up liking books and loving computers. While occasionally burying his nose in books, he was going to computer camp, programming his Radio Shack TRS-80, and playing Pong. His eventual love of reading made him a historian of the book and a connoisseur of print, but as a card-carrying member of the first digital generation—and the father of two digital natives—he understands that we live in electronic times. Book Was There is Piper's surprising and always entertaining essay on reading in an e-reader world.

Much ink has been spilled lamenting or championing the decline of printed books, but Piper shows that the rich history of reading itself offers unexpected clues to what lies in store for books, print or digital. From medieval manuscript books to today's playable media and interactive urban fictions, Piper explores the manifold ways that physical media have shaped how we read, while also observing his own children as they face the struggles and triumphs of learning to read. In doing so, he uncovers the intimate connections we develop with our reading materials—how we hold them, look at them, share them, play with them, and even where we read them—and shows how reading is interwoven with our experiences in life. Piper reveals that reading's many identities, past and present, on page and on screen, are the key to helping us understand the kind of reading we care about and how new technologies will—and will not—change old habits.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Book Was There by Andrew Piper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Publishing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780226103488, 9780226669786eBook ISBN

9780226922898NOTES

PROLOGUE

1. Some highlights: Alberto Manguel, A History of Reading (New York: Viking, 1996); Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, eds., A History of Reading in the West (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999); and Leah Price, “Reading: The State of the Discipline,” Book History 7 (2004): 303–20. On the neuroscience of reading, see Stanislas Dehaene, The Reading Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention (New York: Viking, 2009), and Maryanne Wolf, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (New York: Harper, 2008).

2. As Michael Keller, director of Stanford University’s Libraries, recently remarked about students, “They write their papers online. They read articles online. Many, many, many of them read chapters of books online. I can see in this population of students behaviors that clearly indicate where this is all going.” Laura Sydell, “Stanford Ushers in the Age of Bookless Libraries,” National Public Radio, July 8, 2010, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128361395.

3. See Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: Viking, 2010), and Naomi Baron, Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

4. The fear that there would not be enough readers (and paper) for all the new authors was voiced by Johann Georg Meusel in his eighteenth-century encyclopedia on all living German writers, Das Gelehrte Teutschland, vol. 12 (Lemgo: Meyer, 1806), lxiv. As Christoph Martin Wieland, another contemporary, remarked, “If everyone writes, who will read?” Here is the sentiment in updated form: “Never have so many people written so much to be read by so few.” Katie Hafner, “For Some, the Blogging Never Stops,” New York Times, May 27, 2004, sec. G1. The death of publishing via self-publishing was declared around the most famous case in the eighteenth century, when Friedrich Klopstock, then the German language’s best-known poet, started his own subscription service (it failed). And the fear that people wouldn’t read books anymore (in this case because of newspapers) was voiced by August Prinz in Der Buchhandel vom Jahre 1815 bis zum Jahre 1843 (Altona: Verlags-Bureau, 1855), 26. As scholars like Peter Stallybrass and Leah Price have reminded us, the book has at least since the invention of printing been a minor player in quantitative terms within a larger world of print. As Price writes, “There’s nothing new, then, about the book’s precarious perch within a larger media ecology.” See Leah Price, “Reading as if for Life,” Michigan Quarterly Review 48, no. 4 (2009): 483–98, and Peter Stallybrass, “‘Little Jobs’: Broadsides and the Printing Revolution,” in Agents of Change: Print Culture Studies after Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, ed. Sabrina A. Baron, Eric N. Lindquist, and Eleanor F. Shevlin (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007).

5. A great deal of recent work has tried to develop ways of thinking about media “ecologies” rather than focus on any one particular medium in isolation. See, for example, the work of Matthew Fuller, Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005); N. Katherine Hayles, “Intermediation: The Pursuit of a Vision,” New Literary History 38, no. 1 (2007): 99–125; Dick Higgins, Horizons: The Poetics and Theory of Intermedia (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984); and the ongoing work of our research group in Montreal, “Interacting with Print: Cultural Practices of Intermediality, 1700–1900,” http://interactingwithprint.org/.

6. Alexis Weedon, ed., A History of the Book in the West, 5 vols. (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010); Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and H. R. Woud-huysen, eds., The Oxford Companion to the Book, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose, eds., A Companion to the History of the Book (London: Blackwell, 2009); and David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, eds., The Book History Reader, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2006). There are individual national histories of the book for France, Great Britain, Germany, Ireland, Australia, the United States, Canada, and China.

7. For a notable exception, see the work of Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), and her edited collection, New Media, 1740–1915 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

8. As recent neurological research suggests, when we read we simulate narrative situations in our brain by drawing on our past experiences in the world. Reading is made sense of through this translation between mental simulation and embodied experience. See Nicole K. Speer, Jeremy R. Reynolds, Khena M. Swallow, and Jeffrey M. Zacks, “Reading Stories Activates Neural Representations of Visual and Motor Experiences,” Psychological Science 20, no. 8 (August 2009): 989–99. For recent work that has focused on the historical relationship between bodies and reading books, see Adrian Johns, “The Physiology of Reading: Print and the Passions,” in The Nature of the Book (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 380–443, and Karin Littau, Theories of Reading: Books, Bodies and Bibliomania (Cambridge: Polity, 2007). For work on bodies and digital reading, see Mark Hansen, Bodies in Code (New York: Routledge, 2006), and N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatices (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

CHAPTER 1

1. Saint Augustine, The Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin (New York: Penguin, 1961), 177.

2. Scholars estimate that it was around 300 AD when the codex achieved parity with the scroll. Colin H. Roberts and T. C. Skeat, The Birth of the Codex (London: British Academy, 1983), 75. On Christianity and reading, see Harry Y. Gamble, Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), and Anthony Grafton and Megan Williams, Christianity and the Transformation of the Book: Origen, Eusebius, and the Library of Caesarea (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006).

3. David Katz, The World of Touch, ed. and trans. Lester E. Krueger (Hillsdale, NJ: LEA Publishers, 1989), 226. It was originally published in 1925 as Der Aufbau der Tastwelt (Leipzig: J. A. Barth, 1925). For a recent discussion of the relationship between the human hand and cognition, see Raymond Tallis, The Hand: A Philosophical Inquiry into Human Being (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003). One of the founding works in this field is André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993). Finally, for the argument that we have different neural pathways for our motor and visual relationship to words, see Stanislas Dehaene, The Reading Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention (New York: Viking, 2009), 57. According to neurologists, then, touch is a different cognitive means of knowing language.

4. The Journal of Eugène Delacroix, trans. Lucy Norton (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980), 29.

5. Michael Camille, “Seeing and Reading: Some Visual Implications of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy,” Art History 8, no. 1 (March 1985): 39; Horst Wenzel, “Von der Gotteshand zum Datenhandschuh. Zur Medialität des Begreifens,” Bild, Schrift, Zahl, ed. Sybille Krämer and Horst Bredekamp (Munich: Fink, 2003), 25–55; Meyer Schapiro, Words and Pictures: On the Literal and the Symbolic in the Illustration of a Text (The Hague: Mouton, 1983).

6. John Bulwer, Chirologia, or the Naturall Language of the Hand (1644), n.p.

7. See the delightful introductory study by William H. Sherman, “Toward a History of the Manicule,” Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press, 2008), 25–52.

8. Claire Sherman, ed., Writing on Hands: Memory and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000).

9. See useful catalogs such as The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934, ed. Margit Rowell and Deborah Wye (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2002); Renée Riese Hubert’s Surrealism and the Book (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); and most recently, Anna Sigridur Arnar, The Book as Instrument: Stephane Mallarmé, the Artist’s Book, and the Transformation of Print Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

10. The clasp belongs to the history of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- [PROLOGUE] Nothing Is Ever New

- [ONE] Take It and Read

- [TWO] Face, Book

- [THREE ] Turning the Page (Roaming, Zooming, Streaming)

- [FOUR] Of Note

- [FIVE] Sharing

- [SIX] Among the Trees

- [SEVEN] By the Numbers

- [EPILOGUE] Letting Go of the Book

- Notes