- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Brokered Subjects digs deep into the accepted narratives of sex trafficking to reveal the troubling assumptions that have shaped both right- and left-wing agendas around sexual violence. Drawing on years of in-depth fieldwork, Elizabeth Bernstein sheds light not only on trafficking but also on the broader structures that meld the ostensible pursuit of liberation with contemporary techniques of power. Rather than any meaningful commitment to the safety of sex workers, Bernstein argues, what lies behind our current vision of trafficking victims is a transnational mix of putatively humanitarian militaristic interventions, feel-good capitalism, and what she terms carceral feminism: a feminism compatible with police batons.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brokered Subjects by Elizabeth Bernstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2019Print ISBN

9780226573779, 9780226573632eBook ISBN

9780226573809One

Tracing the “Traffic in Women”

It was just after midnight at the Can Do Bar in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and the mood was light and festive. On a dimly lit street not far from the city’s main nightlife district, the bar that served as the local headquarters of Empower, the most prominent sex worker’s rights organization in the country, was the only storefront still brimming with activity. As was typical for early August, the evening was hot and humid, and many of the women had taken to the outdoor patio while they awaited our arrival, drinking beers and chatting casually. Eager to hear the stories of our recent excursion with an organized “human trafficking tour” of the region, they welcomed us with keen interest, ice-cold drinks, and extra chairs. Within a few minutes, Elena and I were transported worlds away from the increasingly surreal travel experience that had occupied us during the previous seven days, a trip that had been co-organized by a coalition of evangelical Christian and secular NGOs from the United States. Exhausted by our hectic circuit though Bangkok, Chiang Rai, and Chiang Mai—as well as by the emotional strain of traveling with a “delegation” far removed from the needs of the populations that it claimed to represent—we felt relieved to have left the other North American tourists behind and to be there.1

Although the trip had been marketed to us as offering a stark glimpse into the realities of human trafficking, the main difficulties we faced were not due to the heartbreaking encounters with former sex slaves that the tour promised, but instead ensued from the frenetic pace of our travels, the poor coordination of our daily itineraries, a lack of clear communication on the part of the organizers, and the vague yet persistent feeling among many of us that, despite the humanitarian pedigree of the tour’s two sponsoring NGOs, we were somehow being defrauded. Not only were we not introduced to any survivors of trafficking who could offer firsthand testimony of their experiences; many of the meetings with governmental officials and local NGOs that had been promised to us had been abbreviated, rescheduled for odd hours (when the most knowledgeable representatives could apparently not be present), or canceled. Even the “three star” hotels and meals that the NGOs advertised fell short, as we found ourselves crammed into the lowest level of accommodations in each of the cities we visited, and were frequently encouraged to participate in mass tourist staples like elephant rides and visits to handicraft markets in lieu of canceled meetings. When a few members of the group tried to find someone to complain to in order to remedy the situation, we soon discovered that it was impossible to clearly discern upon whom we should pin responsibility, as the sponsoring organizations had in fact subcontracted out the tour to a series of intermediaries—various layers of “consultants” who in fact knew little about the issue and were rarely in our company, as well as one amiable man from the hill tribes of the Northern region of the country who was placed in charge of all logistical considerations, and, we soon discovered, paid a pittance for his time and for actually organizing the tour.2

After hearing some of the stories from our difficult week of travel, Liz, a longtime Empower member, came over to join me and Elena, then a graduate student conducting research for her PhD who was my companion on this journey.3 Liz turned toward me with a poker face and somberly declared, “In our work with women trafficked into the sex sector, we have encountered exactly three cases of women being trafficked that really concerned us in the last few years: yours, Elena’s and one other woman who recently contacted us.”4 After pausing for dramatic effect, she redirected her gaze toward the half dozen or so other women who had gathered around our table to listen to the exchange, who collectively burst into laughter.

The phenomenon of “sex trafficking” is not typically the subject of joking revelry, but Liz’s remark captured the fraughtness of the term from the perspective of many sex worker–activists, as well as their perception of visitors from the Global North who flood places like Thailand with the ambition to help. Elena and I had signed up for this trip in order to learn more about the nature of secular rights-based and evangelical Christian anti-trafficking collaborations, about the increasing commodification of humanitarian sentiment and social justice advocacy, and, most crucially, about the implications of both of these trends for the global politics of sex and gender. “You’ve been trafficked!” the women in the bar exclaimed when we told them the details of our journey, then set about calculating the proceeds that had likely been taken in by the NGOs that had sponsored our excursion, exploiting not only the local recipient communities but also the helping sensibilities of well-intentioned tourists.5

In fact, both Elena and I had already spent several years observing the diverse “helping projects” for sex workers that had sprung up around the globe, tracing the on-the-ground effects of contemporary anti-trafficking campaigns and their affiliated organizations. While I had been studying secular feminist and evangelical Christian activists’ surprisingly close collaborations with the criminal justice system, Elena had been in Bangkok conducting research amid a group of students, expatriates, and full-time missionaries affiliated with an advocacy organization in Los Angeles, shadowing them as they did outreach at go-go bars in one of the city’s principal entertainment districts.6

While enjoying the semblance of an evening breeze, Elena recounted to us how during these bar visits, anti-trafficking activists would offer the dancers alternative employment through their socially entrepreneurial business venture producing and selling jewelry made by “formerly trafficked women.” Nearly all of the “victims” who accepted the offer were slightly older women (in their thirties and forties) who had previously chosen sex work as their highest-paying option but who, after accumulating some savings and finding themselves aging out of the prime markets in sex work, elected jewelry making instead. After accepting their new positions, the women soon discovered that their lives would be governed by some unwelcome regulations: they were officially prohibited from visiting their former colleagues in the red-light district, and their pay would be docked for being minutes late to their shifts, for missing daily prayer sessions, or for minor behavioral infractions. Many also complained about the uniforms that they were required to wear to work: shapeless black polo shirts with the organizational emblem embroidered on the chest, and the Thai word for “freedom” stitched boldly across the right arm.7

The women at the Can Do Bar listened with great interest as we told them these and other stories from our research, and were further intrigued when we showed them our pictures from the tour. Although many of our photographs provoked reactions of bemusement or dismay, it was the last photo we circulated that especially caught their attention. It was a nighttime shot of the anti-trafficking tour participants walking through the Chiang Mai red-light district with knitted brows and worried faces, being led by a young, evangelical woman from the United States who ran a local NGO for sex-trafficked youth (one of a mere handful of anti-trafficking NGOs that our tour group was actually able to meet with). The sex workers’ astonishment reached a pinnacle when they noticed that our photo had also captured a murky image of their friend Nong in the background, who had been standing in front of one of the massage parlors when the anti-trafficking advocates filed past. From the tourists’ troubled expressions of pity and concern, it was clear that they regarded the sex worker who stood in front of them as the very epitome of the “sex trafficking victim” whom they had come so far to help. “But that’s Nong—she is a worker, a mother, not a victim!” the women in the Can Do Bar exclaimed. What’s more, they noted that Nong was an active Empower member who herself had been at the Can Do Bar earlier that evening. Just the week before, she had accompanied them to the annual sex workers’ conference in Kolkata, India, where thousands of women, men, and transgender people from over forty countries and representing some five hundred different organizations had joined together to advocate on behalf of sex workers’ rights.8 A committed activist, Nong was hardly the pitiable victim whom the tourists or their young American colleague had imagined.

The apprehension exhibited by Empower’s sex workers in their collision with current campaigns to combat “sex trafficking” provides the starting point for some of my central concerns in this book. Although the women we met with that evening had not had an easy time working in the sex trade (or, for that matter, in their lives preceding their employment in this sector), they resisted the increasingly prevalent terminology of “trafficking” as an apt description of their experiences.9 Propelled by social circumstance rather than by brute force or organized crime, they were in many ways similar to the sex workers in other regions of the world whom I had worked closely with over the course of several decades. Even those who had begun sex work at young ages, or who had incurred debts to labor brokers, or who had experienced violence at the hands of customers or their employers overwhelmingly rejected this rubric and the implications of its associated lexicon of terms. Indeed, as both the anecdote here and an accumulating corpus of social scientific research have shown, the framework of “trafficking” (along with its attendant notions of sexual victimization and exploitation) has been far better suited to the goals of aid organizations and governments than it has been to the needs of sex workers. It is precisely the efficacy of this discourse for these and other constituencies that the subsequent chapters of the book seek to address.

Only recently have journalists provided the burgeoning “trafficking industrial complex” with a modicum of critical scrutiny, following revelations of falsified public accounts by one of the most high profile and celebrated of anti-trafficking activists, Cambodian “survivor-activist” Somaly Mam. A May 21, 2014 Newsweek cover story drew on years of research for the Cambodia Daily by investigative journalist Simon Marks and featured interviews with family members, neighbors, teachers, and hospital officials.10 Marks not only called into question Mam’s own backstory of sexual servitude (one she had carefully recounted in her best-selling autobiography11) but also debunked one of her foundation’s most circulated stories of victim salvation. Among Mam’s chief fund-raising vehicles was the story of Long Pross, presented as a young trafficking victim who had lost her eye to a brutal attack from the brothel owner. The Newsweek story revealed that the young girl had in fact suffered the injury after the surgical removal of a tumor, and that she had been placed at Mam’s foundation at her parents’ request because they were too poor to provide for her. After the release of the Newsweek exposé, not only was Mam herself forced to resign from her post as the Foundation’s head, but her defenders were briefly spurred to consider the broader implications of her fictions.12

Over the past few years, there has also been a growing body of academic writing on particular communities of sex workers and the gaps and disjunctures between their experiences and those that have been asserted by the official trafficking discourse. In her study of migrant Filipina sex workers working in South Korea, for example, the anthropologist Sealing Cheng has found that their experiences “defy the binaries . . . of innocent Third World women vs. powerful First World men; well-intentioned nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) vs. evil-intentioned employers; the protection and shelter of rescuers vs. the danger of the clubs; and the risks of migration vs. the safety of home.”13 Taking issue with prevailing abolitionist accounts of the relations of force and coercion inherent in brothel-based prostitution in India, Svati Shah has likewise demonstrated through her careful ethnographic study of prostitution in Mumbai that sexual commerce “is not a totalizing context for everyone who sells sexual services,” but rather one form of economic survival among many for rural migrants in the informal sector.14 Writing about the situation of sex workers from the former Soviet states who have come to Norway, Christine Jacobsen and May-Len Skilbrei draw on extensive interview-based data to provide a sharp contrast between the women’s own self-representations and the accounts of victimhood that prevail in international trafficking discourse. In particular, they note that prostitution, for their interviewees, is forced on them neither by cruel men nor by situations of dire economic hardship, but rather provides much coveted access to “consumption and leading lifestyles associated with ‘modernity’ and ‘the West.’”15

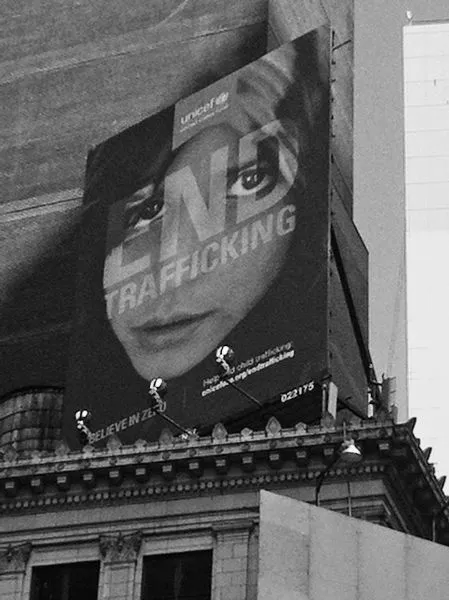

Although the disparities between sex workers’ experiences and the presumptions of contemporary anti-trafficking campaigns have been critically noted by various commentators, the significance of this disjuncture has yet to be adequately described. Why did narratives of sex trafficking suddenly reemerge after almost a century of slumber, resuscitating long-dormant accounts of the horrors of the “white slave” trade? How was the idea of a global “traffic in women” resurrected out of the framework of prostitution as a victimless crime, which prevailed in the 1960s and 1970s, and the gathering movement for sex workers’ rights, which gained prominence over the following two decades? And what is it, precisely, that has enabled “trafficking” to travel so well—across secular and religious divides, across geographic borders, and across wildly variant activist constituencies? In law and policy and the mass media, on college campuses, in church pews and in corporate social responsibility campaigns, the “sex-trafficking victim” has become an iconic figure of our era, capacious enough to serve as the emblem for quite disparate imaginations of social suffering. In recent years, she has become a nearly ubiquitous symbol of gender inequality and exploited labor, of open borders and unbridled commodification, and of myriad forms of sexual violence.16 While she has periodically shared the spotlight with a range of other iconic figures of sexual exploitation—from the burkha-clad Muslim woman to the presumptively white victims of sexual assault on college campuses and in elite workspaces—the image of the trafficking victim has been durable as well as malleable.17 An initial aim of this book is thus to interrogate this image and to understand the work it does in the diverse sites of anti-trafficking activity that it has come to inhabit, even as it often fails to adequately capture what it purports to describe.

Like the various phenomena that are signaled by the term “trafficking” itself, the individuals and institutions that make up its associated “rescue industry” circulate through multiple layers of symbolic and material intermediaries.18 As I describe in the pages that follow, these include local, state, and transnational governing institutions, secular feminist and faith-based activist campaigns, and a bevy of nonprofit as well as for-profit ventures that have recently emerged to “end sex trafficking” and to help victims. As in other forms of neoliberal governance, these “brokers and translators” are rarely questioned in terms of the beneficence of their motives or the effects of their interventions.19 Given the complex chains of brokerage and connectivity that characterize much of contemporary political and economic life, a second aim of this book is to consider how and why certain kinds of social relations get singled out for moral and political redress, and the role that sex and gender play in forging these distinctions.

1.1 UNICEF anti-trafficking promotional campaign poster, on display in Midtown Manhattan. Photo: Elena Shih, 2013.

The final question that this study considers is suggested by both the opening anecdote of this chapter and the subtitle of this book. Like the sex workers in the Can Do Bar who listened in astonishment to our stories of activists’ efforts on their behalf, we need to more closely interrogate the political implications of Western helping campaigns that are organized around women’s carceral control, intimate refashioning, and purportedly redemptive labor. Looking beyond the specific contours of the case study at hand, this investigation should spur us to reexamine not only the kinds of social relations that are considered most exploitative—that is, those that, in prevailing versions of the anti-trafficking discourse, are deemed “tantamount to slavery”—but also to critically interrogate current imaginations of gendered progress and freedom.20 At stake is the vision that is shared by contemporary activist campaigns to combat “sex trafficking,” as well as an emergent and expanding set of mechanisms of global governance (often proceeding under the banners of “women’s rights” and “empowerment”) more generally.

A Genealogy of “Sex Trafficking”

I came to these queries via a particular ethnographic circuitry, one that, over the course of the pa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Tracing the “Traffic in Women”

- 2 The Sexual Politics of Carceral Feminism

- 3 Seek Justice™

- 4 The Travels of Trafficking

- 5 Redemptive Capitalism and Sexual Investability

- 6 Imagining Freedom

- Afterword

- Notes

- References

- Index