- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

German artist Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948) is best known for his pioneering work in fusing collage and abstraction, the two most transformative innovations of twentieth-century art. Considered the father of installation art, Schwitters was also a theorist, a Dadaist, and a writer whose influence extends from Robert Rauschenberg and Eva Hesse to Thomas Hirschhorn. But while his early experiments in collage and installation from the interwar period have garnered much critical acclaim, his later work has generally been ignored. In the first book to fill this gap, Megan R. Luke tells the fascinating, even moving story of the work produced by the aging, isolated artist under the Nazi regime and during his years in exile.

Combining new biographical material with archival research, Luke surveys Schwitters's experiments in shaping space and the development of his Merzbau, describing his haphazard studios in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom and the smaller, quieter pieces he created there. She makes a case for the enormous relevance of Schwitters's aesthetic concerns to contemporary artists, arguing that his later work provides a guide to new narratives about modernism in the visual arts. These pieces, she shows, were born of artistic exchange and shaped by his rootless life after exile, and they offer a new way of thinking about the history of art that privileges itinerancy over identity and the critical power of humorous inversion over unambiguous communication. Packed with images, Kurt Schwitters completes the narrative of an artist who remains a considerable force today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kurt Schwitters by Megan R. Luke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Radiating Space

What could have possibly prepared visitors who called on Kurt Schwitters at his home in Hannover for their encounter with his now-legendary Merzbau (see plates 1–4)? Within numerous artistic networks active in Central Europe throughout the 1920s, he had enjoyed widespread acclaim for his performative poetry and intimately scaled abstract collages. By the time he fled Germany for Norway in January 1937, this sculptural environment of unprecedented ambition and scope had taken root in his studio and extended through several rooms and on various floors of his family’s house. The Merzbau thereby signaled a decisive turning point, both for the artist’s own aesthetic concerns and for the history of art more generally. Schwitters used it to focus his efforts on the articulation of space and the choreography of its apprehension and, in the process, radically destabilized accepted norms of what a sculpture could be. Destroyed during the Second World War in an Allied air raid in 1943, the Merzbau survives today through a small cache of photographs and the contradictory anecdotes of numerous eyewitnesses, often recorded decades after their disorienting confrontations with the work and its maker. Taking their cue from these accounts, art historians have insisted on the continuity of this project with Schwitters’s work in collage, assuming a smooth and unproblematic extension of his pictorial practice into “real” space.1 Yet are we entirely clear on how, precisely, he bridged this leap into three dimensions?

Together with its later iterations during Schwitters’s exile in Norway and England, the Merzbau registered how completely he transformed his practice, first when confronted with the exuberant internationalism of artists working in the wake of cubism and Dada and then again in response to their diaspora following Hitler’s ascent to power. Schwitters pursued sculpture in earnest only after intense collaborative research into spatial composition. He understood the perceptual demands of this medium to be independent from his early emphases on pictorial framing and the harmony of part/whole relationships, which he had enlisted to transform the refuse of urban life into abstractions of pure color and texture. The Merzbau cemented his turn away from the picture plane conceived as a guarantor for compositional organization and coherence, and it registered instead his newfound interest in the dynamic interchange between artwork and beholder in a shared space. However, analyses of the Merzbau are overwhelmingly preoccupied with its material heterogeneity—a focus on its origins that symptomatically disavows the trauma of its loss to wartime violence. All have relied upon Schwitters’s own intentionally mystifying account of his studio activities written in 1930, in which he cataloged the disparate fragments that made up the unruly structure he called his Kathedrale des erotischen Elends (Cathedral of Erotic Misery). For many historians, the source of the Merzbau lay in the fetishistic grottoes of this “cathedral” and in its other totemic objects, such as the death mask of his first son, a broken hurdy-gurdy, Christmas lights, a suspended flask of his urine, and so forth.2 To this day, the potentially explosive spatial consequences for a practice once confined by abstract composition and the planarity of collage remain conspicuously unspoken. Attention to the materiality of the Merzbau certainly has the potential to disrupt its easy sublimation into a reproducible inscription of light and shadow onto the flat, circumscribed plane of photography. Nevertheless, our fascination with Schwitters’s antihierarchical, possibly scatological manipulation of any-material-whatsoever has inadvertently conspired with the structure’s survival as written discourse and, more importantly, as photographic image to prolong the very “space-phobia” (Raumscheu) characteristic of modernism in the visual arts that the Merzbau was intended to foreclose once and for all.3

Long before the Merzbau was reduced to rubble—indeed, at the threshold of its very conception—Schwitters actually articulated a sophisticated theory about how we construct and perceive space that resisted the paradigm of pictorial composition. He only came to describe the spatial dimension of painting, sculpture, and architecture after a period of sustained work as a graphic designer, during which he participated in intense discussions with numerous artists about the typography of the printed page. Yet rather than publish his conclusions in his own Merz magazine or in any of the avant-garde and architectural journals to which he regularly contributed, he ultimately chose to broadcast them through performance and photography in a series of didactic slide lectures throughout Germany. He gave his last known presentation of this lecture on April 3, 1930, for the Frankfurter Bund für künstlerische Gestaltung (Frankfurt Union for Artistic Design), which he titled “Gestaltung in Kunst, Architektur und Typographie” (Formation in Art, Architecture, and Typography).4 All that remain are seventeen pages of his shorthand notes on twenty-nine individual examples of recent painting, sculpture, architecture, and typographical designs culled from his collection of glass slides. Forty-nine of these slides survived his exile from Nazi Germany, and they are preserved today at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover. In addition, three differently dated slide lists demonstrate that he delivered earlier versions of this lecture to various unions of graphic designers and architects in Berlin (June 9, 1929), Stuttgart (November 8, 1929), and Hannover (February 13, 1930). They show that he steadily reduced the number of images he projected and revised their sequence as the tour progressed. These talks were likely based on a more extensive lecture he presented in January 1929 at the Amsterdam School of Music at the invitation of the architectural group de 8.5

Schwitters used this tour to describe a recent revolution in the history of modernist form, charting how artists and architects of his generation challenged conventional methods for the illusionistic representation and corporeal manipulation of space. Over the course of the year when he delivered this itinerant lecture in Germany, he successively refined his selection of images. In each version, however, his analysis of effective typography relied exclusively on examples of the work of fellow members of the ring neue werbegestalter (Ring of New Advertising Designers), a loose union of graphic designers he established in 1927. This discussion always concluded a lengthy retrospective assessment of the pervasive concern among his contemporaries with Raumgestaltung, the formation of space. To illustrate this concept, he first examined abstract painting and sculpture, contrasting work in these media to the architectural designs by members of Der Ring in Germany and by affiliates of De Stijl in the Netherlands. Schwitters also took care to integrate specific examples of his earliest work in assemblage within the context of his analysis of the art and design of an international network of peers. Hence this lecture also provided him the opportunity to look back on a decade of his Merz practice at a moment when his work was undergoing a seismic shift as dramatic as his initial embrace of abstraction and collage. As he abandoned a fundamentally pictorial practice in order to shape whole environments, he assessed his earliest avant-garde gestures in tandem with a systematic review of contemporary art and design, summarizing what Merz was and making a case for how it would change in the years to come.

Remarkably, these unpublished lecture notes, slide lists, and glass slides are the only sources for a theory of space that we have from the creator of the Merzbau. The textual record is telegraphic and elliptical, yet it was never meant to be anything other than a supplement to a narrative that would unfold through images projected in light, repeatedly and in various locations. As Schwitters synthesized his rapidly changing ideas about spatial experience, the performance of a slide lecture could visualize his arguments and make them literally palpable for his audiences. His sequence of images, together with his notes, articulated a remarkable confluence of aesthetic problems, including the constitutive function of the frame for any work of art, the demands of composition and the special priority of the center, the possibility for movement within an image, the status of individual artistic media and their common purpose, the validity of all material for artistic formation, and the combination of these materials into a unified whole. Through this lecture Schwitters offered his own history of spatial configuration in the new art and architecture of his day, inaugurating a preoccupation with space that we must reconstruct and contextualize if we are to understand the conceptual stakes of the Merzbau and how this work would come to dominate his practice in the 1930s.

Space and Composition in the New Typography

The ring neue werbegestalter joined together key figures working in Germany and the Netherlands who aimed to promote and popularize modern graphic design, which was immediately recognizable by sans serif typefaces and spare, syncopated compositions employing strong diagonals and generous negative space. Apart from Schwitters, members included Willy Baumeister, Max Burchartz, Walter Dexel, César Domela, Hans Leistikow, Robert Michel, Paul Schuitema, Jan Tschichold, Georg Trump, Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, and Piet Zwart. Together they frequently exhibited with kindred designers from the Bauhaus, and indeed they shared the school’s mission to cooperate with industry in the widespread promulgation of modernist form. In comparison to the Soviet contemporaries whose work they greatly admired, the attitude of the ring was less revolutionary and utopian in spirit and rather more educative and promotional.6 In his capacity as chairman of the group, Schwitters proposed that it fund a collection of glass slides that would serve as an archive of members’ work to be kept in Hannover. This collection could be made available to members on loan as needed for lectures.7 These lectures served to advance the trends of Neue Typographie (New Typography) and the activities of the group much like two collections of members’ designs that toured in exhibitions throughout Germany and to select cities in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden. A defining characteristic of Neue Typographie was its exclusive use of photographic illustration, and in Schwitters’s hands it would also be the chief vehicle for its wider dissemination.

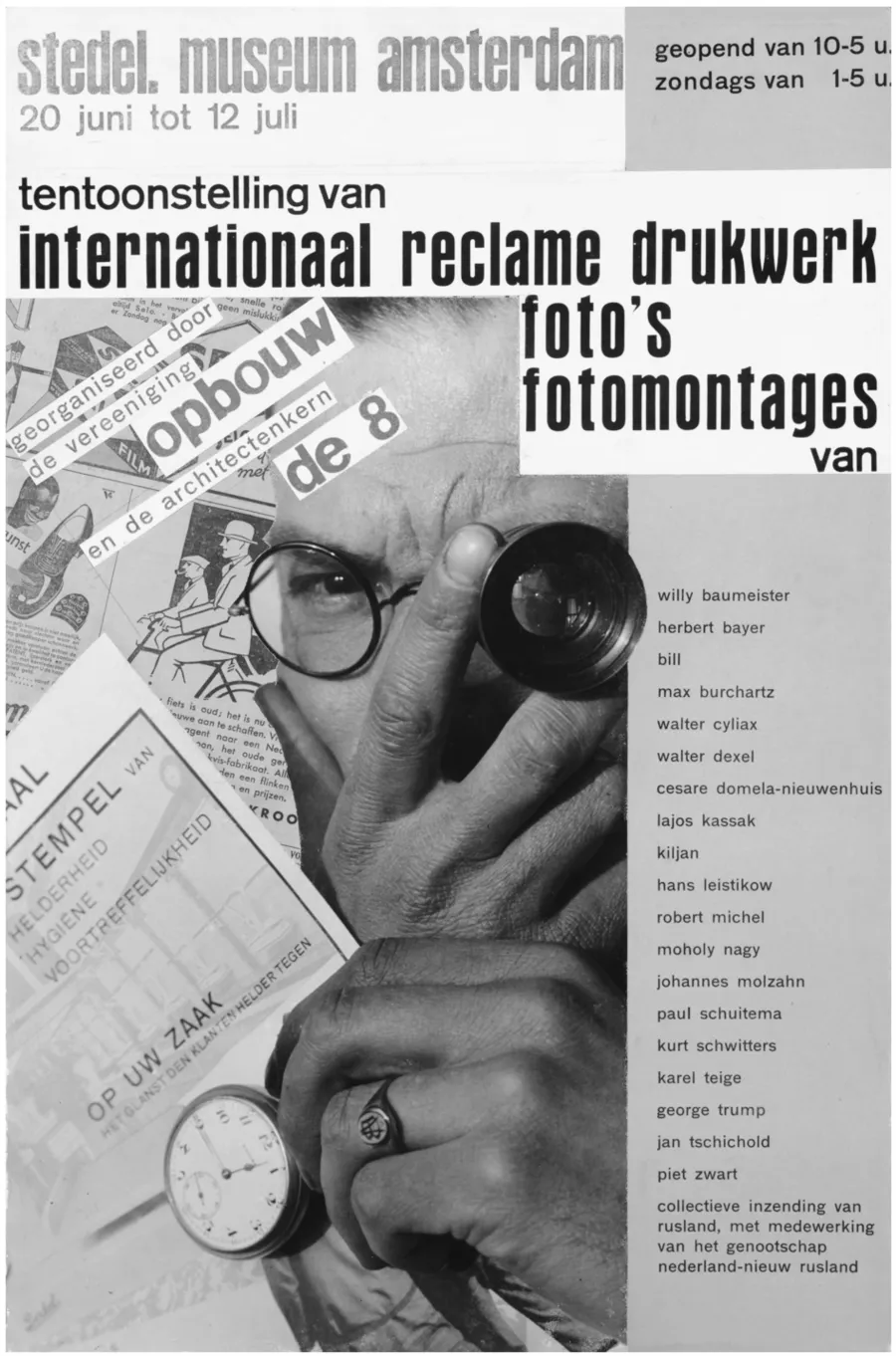

FIG. 7. Paul Schuitema, poster for the exhibition of the ring neue werbegestalter at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1931. Courtesy Martin Schuitema and Dick Maan.

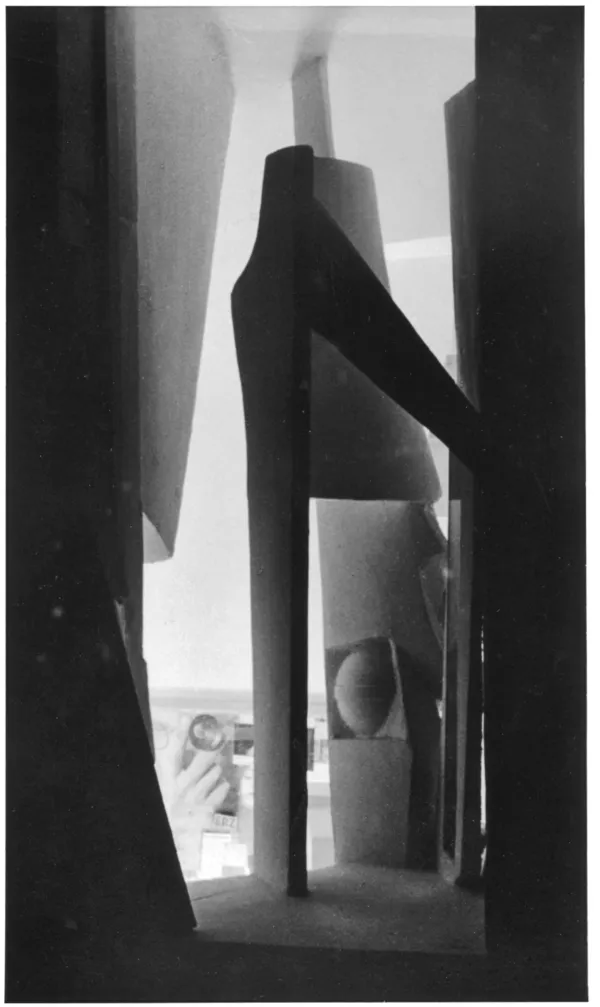

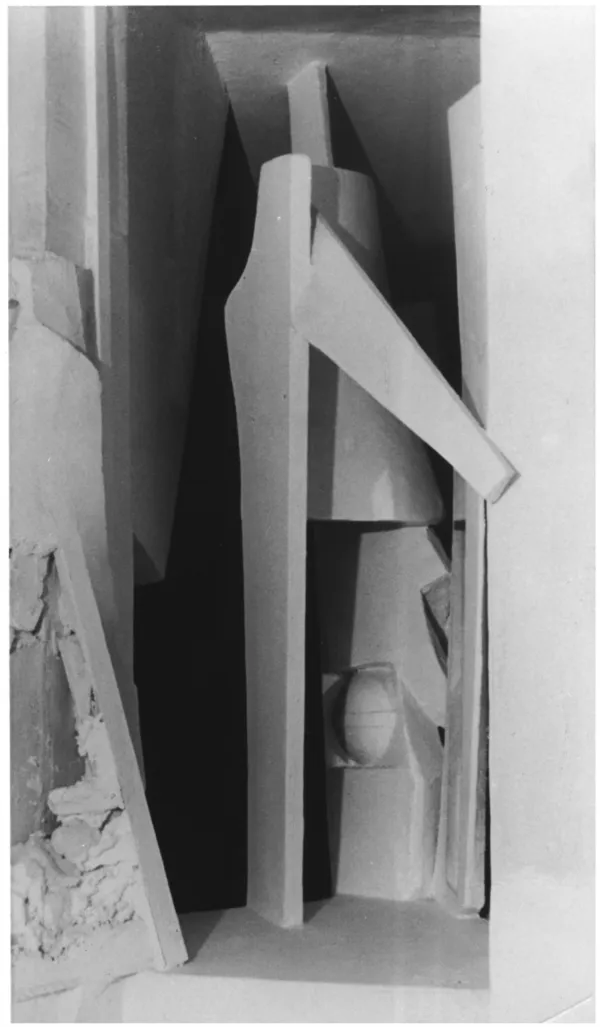

The last official exhibition of the ring was mounted in 1931 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, organized by de 8 and the Rotterdam architects’ association, Opbouw. This opportunity was secured for the group by the most recent addition to its roster, Paul Schuitema, whose poster for the exhibition prominently included a photographic self-portrait (fig. 7). In this image, a bespectacled Schuitema holds up a loupe to his left eye, nearly covering his entire face with his right hand. These prostheses to his vision double for the very camera lens to which he directs his gaze. Schwitters later included this image in what appears to be a collage that hung within the Merzbau, evident in a little-known photographic detail of the space taken by his son Ernst from within its sculptural constructions (fig. 8). While it is not known where exactly in the Merzbau this image was taken, it is most likely one of the photographs Ernst took at the end of 1936, two days before his final departure from Germany. Schwitters helped his son in his campaign to interpret the entire space photographically, and he “experienced the atelier in its entirety once more in this way.” When Ernst gave these images to his father for his fiftieth birthday, celebrated a few months after both had relocated to Norway in exile, he wrote: “The double image is not a positive and a negative, as one might be tempted to think, but the same spot in two different kinds of light. I printed the two images next to one another so that you can use these pictures to demonstrate the importance of proper lighting, the possibilities for lighting, and the design of lighting [Lichtgestaltung].”8 More than any other image of the Merzbau, this double-photograph makes explicit the paradigm of light projection for the spatial ambitions of this environment—specifically a light projection informed by the didactic and promotional activities of the ring and the communicative goals Schwitters advocated for graphic design.

FIG. 8. Kurt Schwitters, detail of the Hannover Merzbau, apparently viewed from the south wall, 1933. Destroyed (1943). Photo: Kurt Schwitters Archives at the Sprengel Museum Hannover. Photographer: Ernst Schwitters. Repro: Michael Herling / Aline Gwose, Sprengel Museum Hannover. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Indeed, Schuitema had proposed an international magazine devoted to advertising design, with the idea that it would be represented in the Soviet Union by El Lissitzky, in Prague by Karel Teige, in Vienna by Lajos Kassák, and in Germany by Schwitters. Schwitters declined to take on this project, but when no other member of the ring volunteered, he proposed that the group publish a series of monographs devoted to the work of each member patterned after the publications generated by the architects of Der Ring, the union that had served as the prototype for their organization. After all, the ring already had standing agreements with Das neue Frankfurt and the Werkbund’s Die Form, periodicals devoted primarily to architecture and urbanism, to publish the designs and texts of its members. However, as funding remained a serious problem, Schwitters narrowed his ambition to publ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Radiating Space

- 2. The Wandering Merzbau

- 3. For the Hand

- Color Plates

- 4. The Image in Exile

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index