![]()

PART III

Toward a More General Theory of Punishing and Policing

Today, we deploy the general in order to individualize—in order to make a better judgment in the case of “any given man.”1 In order to devise the right punishment “for each man about to be paroled.”2 We place people in categories and assess risk factors in order to know the individual better. The actuarial did not grow out of a desire to disregard the individual. It did not grow out of a preference for the general over the particular. To the contrary, it grew out of our lust to know the individual. To know this individual. To tailor punishment to the particularities and probabilities of each man. This is, paradoxically, the triumph of the individualization of punishment. Today, we generalize to particularize.

Tragically, though, we are blinded by our lust for knowledge, for prediction, for science. We ignore the complexity of elasticities in order to indulge our desire for technical expertise. We make simplifying assumptions. And we model—incorrectly. What we need to do, instead, is to rigorously analyze the actuarial in much the same way that it analyzes us. And when we do that, we will be surprised to learn that its purported efficiencies are probably counterproductive—that they may increase rather than decrease the overall rate of targeted crime; that they may produce distortions in our prison populations with a ratchet effect on the profiled groups; and that they may blind us to our own sense of justice and just punishment.

Carol Steiker captures this dilemma well by analogy to “the old chestnut about the man looking for his car keys under a street lamp yards away from his car. When asked why he is looking all the way over there, he replies, ‘Because that’s where the light is.’”3 As Steiker suggests, the appropriate question may be “Why are so many in the world of criminal justice clustering under the street lamp of predicting dangerousness?”

In this final part, I step back from the details of the three critiques to generalize about the force of the argument. I set forth a more general framework for analyzing the particular uses of actuarial instruments in the criminal law. I begin by exploring the specific cases of racial profiling on the highways in chapter 7 and of the 1960s bail-reform initiatives in chapter 8, as vehicles to elaborate the more general framework. In the concluding chapter, I discuss the virtues of randomization.

![]()

CHAPTER SEVEN

A Case Study on Racial Profiling

In the actuarial field, the case of racial profiling on the highways has received perhaps the most attention from social scientists, legal scholars, and public policymakers. As a result, it is the subfield with the most abundant empirical data and economic models. It seems only fair to ask, at this point, what the empirical evidence shows: Does racial profiling on the roads reduce the overall incidence of drug possession and drug trafficking on the nation’s highways? Does it produce a ratchet effect on the profiled population? And does it distort our shared conceptions of just punishment?

Unfortunately, as noted in chapter 3, the new data on police searches from across the country do not provide reliable observations on the key quantities of interest necessary to answer these questions precisely. Specifically, the data do not contain measures of comparative offending or elasticity, nor of natural offending rates within different racial groups. Nevertheless, it is possible to make reasonable conjectures based on both the best available evidence and conservative assumptions about comparative offending rates and elasticities. Let’s proceed, then, cautiously.

Comparative Drug-Possession and Drug-Trafficking Offending Rates

The term offending rate can be defined in several ways. First, it can refer to the rate of actual offending in the different racial groups, given the existing distribution of police searches. This I will call the “real offending rate.” It is calculated by dividing the total number of members of a racial group on the road who are carrying drug contraband by the total number of persons of that racial group on the road. This is a quantity of interest for which we do not have a good measure. Second, the offending rate may be defined as the actual rate of offending in a racial group when the police are sampling randomly—that is, when they are engaged in color-blind policing. This I will call the “natural offending rate.” Now, it is not entirely natural because, if offending is elastic, it will depend on the amount of policing. But it is natural in the sense that, as between racial groups, there is no racial profiling effect. This definition of the offending rate can be measured only under conditions of random sampling. While hard to measure, it represents the only proper way to obtain a metric that we can use to compare offending among different racial groups.

Under assumptions of elasticity, the “real offending rate” will fluctuate with policing. The “real offending rate,” by definition, will be the same as the “natural offending rate” when the police engage in random searches. If the police stop and search more minority motorists, then the real offending rate for minorities will be smaller than their natural offending rate—again, assuming elasticity. Under assumptions of low or no elasticity, changes in policing will cause little to no fluctuation in the real offending rate. The real offending rate will equal the natural offending rate no matter how disproportionate the policing—no matter how much profiling takes place.

In all of this, naturally, the offending rate must be distinguished from the “hit rate”—the rate of successful searches for drug contraband. The two are related because the offending rate feeds the search success rates. However, the hit rate is generally going to be much higher than the offending rate because the police search selectively and identify likely offenders.

With these definitions in mind, it is important to clarify the expression “minority motorists have higher offending rates than white motorists.” When someone who believes in rational-action theory makes this claim, then they must be talking about higher natural offending rates. Certainly, this is true of economists. The whole idea behind the economic model of racial profiling is that disproportionate searches of minority motorists will, as a result of elasticity, bring down their real offending rate to the same level as that of white motorists. When the hit rates are equal, the real offending rates should be equal as well. Yet even when the real rates of offending are the same, the assumption is that minority motorists have higher natural rates of offending. This explains the need for disproportionate searches of minorities.1

In contrast, when someone who believes that individuals are inelastic to policing makes the claim that “minority motorists have higher offending rates than white motorists,” then the term offending rate can refer either to real or natural offending rates because the two are essentially identical.

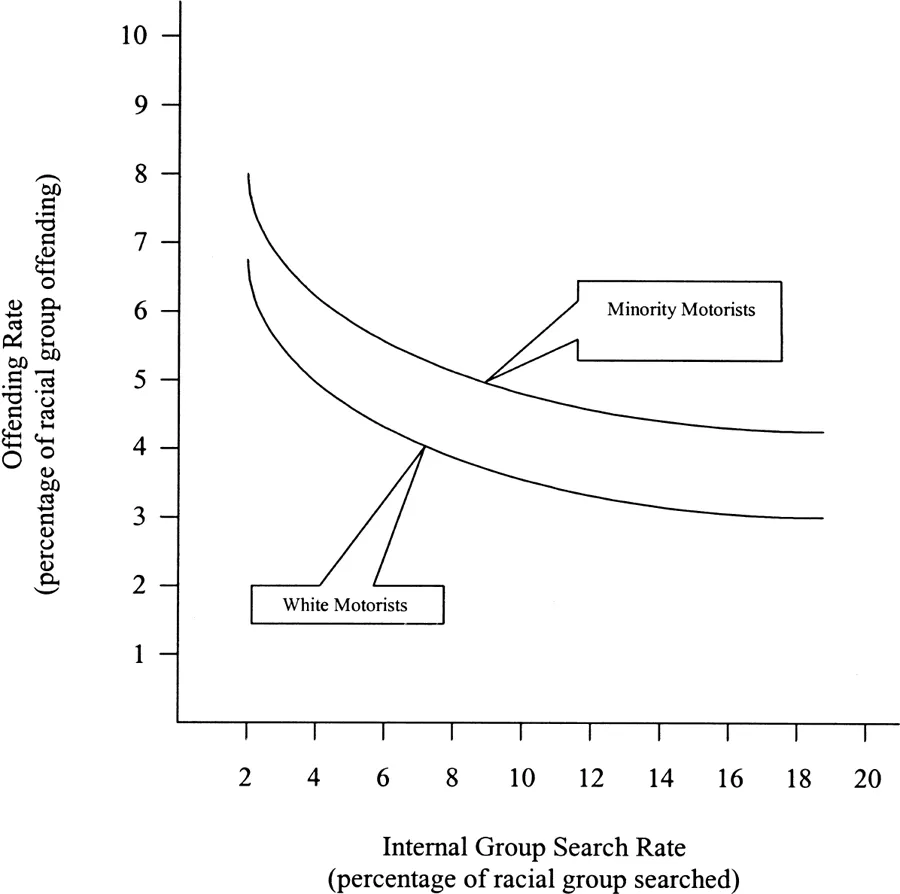

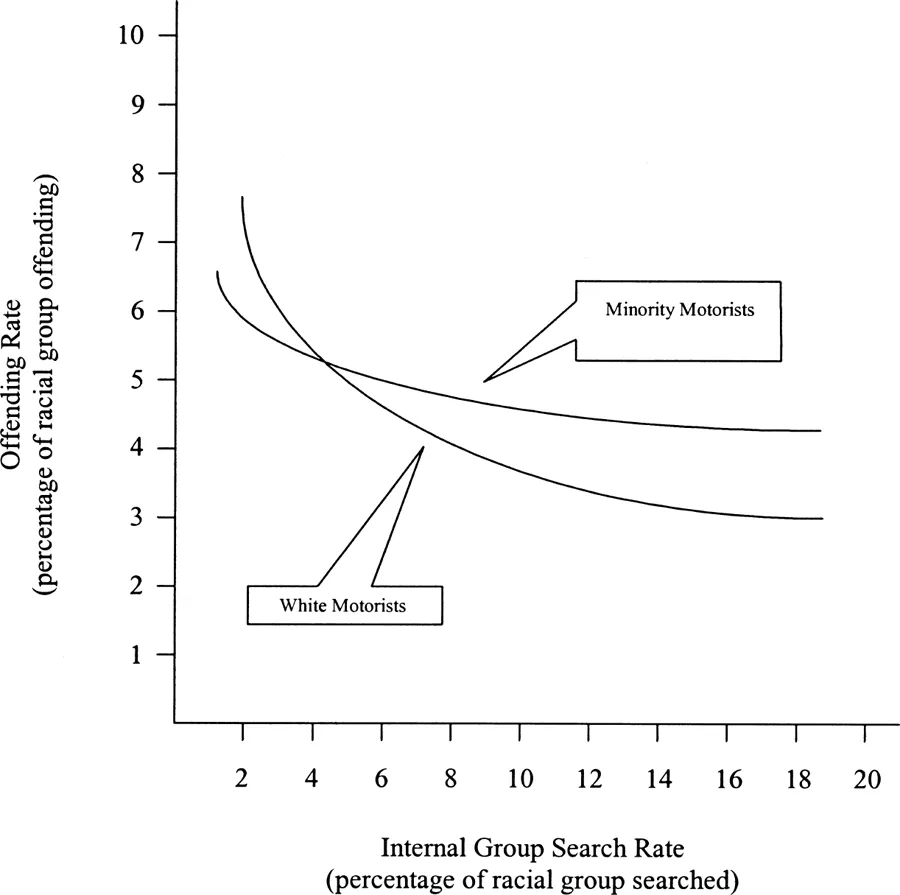

Now, under assumptions of elasticity, might the different offending rates of different racial groups nevertheless intersect at some point? Perhaps, though this is a point of ambiguity. When an economist says, “minority motorists have higher offending rates,” it simply is not clear whether they mean “at each and every comparative degree of searching” or only “for the most part.” In other words, the offending rates could possibly intersect at higher rates of searches. In effect, the offending rates could look like either of the two graphs—or any permutation of these graphs—shown in figures 7.1 and 7.2.

These two graphs depict very different elasticities of offending to policing between members of the different racial groups, and the different elasticities affect whether the natural offending rates are consistently or mostly greater for minority motorists. This in turn has important implications for whether racial profiling reduces the amount of profiled crime and for the extent of the ratchet effect on the profiled population.

FIGURE 7.1 Consistently higher offending among minority motorists

FIGURE 7.2 Mostly higher offending among minority motorists

To estimate natural offending rates, it is also important to distinguish between types of violators: persons carrying drugs for personal use versus drug traffickers. We may also need to explore offending rates by different illicit drugs, given that there may be significant racial differences depending on th...