- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

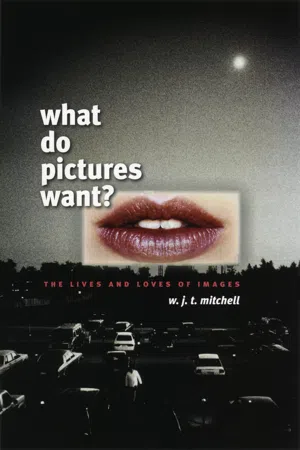

Why do we have such extraordinarily powerful responses toward the images and pictures we see in everyday life? Why do we behave as if pictures were alive, possessing the power to influence us, to demand things from us, to persuade us, seduce us, or even lead us astray?

According to W. J. T. Mitchell, we need to reckon with images not just as inert objects that convey meaning but as animated beings with desires, needs, appetites, demands, and drives of their own. What Do Pictures Want? explores this idea and highlights Mitchell's innovative and profoundly influential thinking on picture theory and the lives and loves of images. Ranging across the visual arts, literature, and mass media, Mitchell applies characteristically brilliant and wry analyses to Byzantine icons and cyberpunk films, racial stereotypes and public monuments, ancient idols and modern clones, offensive images and found objects, American photography and aboriginal painting. Opening new vistas in iconology and the emergent field of visual culture, he also considers the importance of Dolly the Sheep—who, as a clone, fulfills the ancient dream of creating a living image—and the destruction of the World Trade Center on 9/11, which, among other things, signifies a new and virulent form of iconoclasm.

What Do Pictures Want? offers an immensely rich and suggestive account of the interplay between the visible and the readable. A work by one of our leading theorists of visual representation, it will be a touchstone for art historians, literary critics, anthropologists, and philosophers alike.

According to W. J. T. Mitchell, we need to reckon with images not just as inert objects that convey meaning but as animated beings with desires, needs, appetites, demands, and drives of their own. What Do Pictures Want? explores this idea and highlights Mitchell's innovative and profoundly influential thinking on picture theory and the lives and loves of images. Ranging across the visual arts, literature, and mass media, Mitchell applies characteristically brilliant and wry analyses to Byzantine icons and cyberpunk films, racial stereotypes and public monuments, ancient idols and modern clones, offensive images and found objects, American photography and aboriginal painting. Opening new vistas in iconology and the emergent field of visual culture, he also considers the importance of Dolly the Sheep—who, as a clone, fulfills the ancient dream of creating a living image—and the destruction of the World Trade Center on 9/11, which, among other things, signifies a new and virulent form of iconoclasm.

What Do Pictures Want? offers an immensely rich and suggestive account of the interplay between the visible and the readable. A work by one of our leading theorists of visual representation, it will be a touchstone for art historians, literary critics, anthropologists, and philosophers alike.

"A treasury of episodes—generally overlooked by art history and visual studies—that turn on images that 'walk by themselves' and exert their own power over the living."—Norman Bryson, Artforum

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What Do Pictures Want? by W. J. T. Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Images

Image is everything.

Andre Agassi, Canon Camera commercial

THE OBSERVATION THAT “image is everything” has usually been a matter of complaint, not celebration, as it is in Andre Agassi’s notorious declaration (made long before he shaved his head, changed his image, and became a real tennis star instead of a poster boy). The purpose of this first section is to demonstrate that images are not everything, but at the same time to show how they manage to convince us that they are. Part of this is a question of language: the word image is notoriously ambiguous. It can denote both a physical object (a painting or sculpture) and a mental, imaginary entity, a psychological imago, the visual content of dreams, memories, and perception. It plays a role in both the visual and verbal arts, as the name of the represented content of a picture or its overall formal gestalt (what Adrian Stokes called the “image in form”); or it can designate a verbal motif, a named thing or quality, a metaphor or other “figure,” or even the formal totality of a text as a “verbal icon.” It can even pass over the boundary between vision and hearing in the notion of an “acoustic image.” And as a name for likeness, similitude, resemblance, and analogy it has a quasilogical status as one of the three great orders of sign formation, the “icon,” which (along with C. S. Peirce’s “symbol” and “index”) constitutes the totality of semiotic relationships.1

I am concerned here, however, not so much to retrace the ground covered by semiotics, but to look at the peculiar tendency of images to absorb and be absorbed by human subjects in processes that look suspiciously like those of living things. We have an incorrigible tendency to lapse into vitalistic and animistic ways of speaking when we talk about images. It’s not just a question of their producing “imitations of life” (as the saying goes), but that the imitations seem to take on “lives of their own.” I want to ask, in the first chapter, precisely what sort of “lives” we are talking about, and how images live now, in a time when terrorism has given new vitality to collective fantasy, and cloning has given a new meaning to the imitation of life. In the second chapter I turn to a model of vitality based in desire—in hunger, need, demand, and lack—and explore the extent to which the “life of images” expresses itself in terms of appetites. In the third chapter (“Drawing Desire”) I turn this question around. Instead of asking what pictures want, I raise the question of how we picture desire as such, especially in that most fundamental form of picture-making we call “drawing.” Finally (in “The Surplus Value of Images”), I will turn to the question of value, and explore the tendency to both over- and underestimate images, making them into “everything” and “nothing,” sometimes in the same breath.

1

Vital Signs | Cloning Terror*

One never knows what a book is about until it is too late. When I published a book called Picture Theory in 1994, for instance, I thought I understood its aims very well. It was an attempt to diagnose the “pictorial turn” in contemporary culture, the widely shared notion that visual images have replaced words as the dominant mode of expression in our time. Picture Theory tried to analyze the pictorial, or (as it is sometimes called) the “iconic” or “visual,” turn, rather than to simply accept it at face value.1 It was designed to resist received ideas about “images replacing words,” and to resist the temptation to put all the eggs in one disciplinary basket, whether art history, literary criticism, media studies, philosophy, or anthropology. Rather than relying on a preexisting theory, method, or “discourse” to explain pictures, I wanted to let them speak for themselves. Starting from “metapictures,” or pictures that reflect on the process of pictorial representation itself, I wanted to study pictures themselves as forms of theorizing. The aim, in short, was to picture theory, not to import a theory of pictures from somewhere else.

I don’t meant to suggest, of course, that Picture Theory was innocent of any contact with the rich archive of contemporary theory. Semiotics, rhetoric, poetics, aesthetics, anthropology, psychoanalysis, ethical and ideological criticism, and art history were woven (probably too promiscuously) into a discussion of the relations of pictures to theories, texts, and spectators; the role of pictures in literary practices like description and narration; the function of texts in visual media like painting, sculpture, and photography; the peculiar power of images over persons, things, and public spheres. But all along I thought I knew what I was doing, namely, explaining what pictures are, how they mean, what they do, while reviving an ancient interdisciplinary enterprise called iconology (the general study of images across the media) and opening a new initiative called visual culture (the study of human visual experience and expression).

Vital Signs

Then the first review of Picture Theory arrived. The editors of The Village Voice were generally kind in their assessment, but they had one complaint. The book had the wrong title. It should have been called What Do Pictures Want? This observation immediately struck me as right, and I resolved to write an essay with this title. The present book is an outgrowth of that effort, collecting much of my critical output in image theory from 1994 to 2002, especially the papers exploring the life of images. The aim here is to look at the varieties of animation or vitality that are attributed to images, the agency, motivation, autonomy, aura, fecundity, or other symptoms that make pictures into “vital signs,” by which I mean not merely signs for living things but signs as living things. If the question, what do pictures want? makes any sense at all, it must be because we assume that pictures are something like life-forms, driven by desire and appetites.2 The question of how that assumption gets expressed (and disavowed) and what it means is the prevailing obsession of this book.

But first, the question: what do pictures want? Why should such an apparently idle, frivolous, or nonsensical question command more than a moment’s attention?3 The shortest answer I can give can only be formulated as yet another question: why is it that people have such strange attitudes toward images, objects, and media? Why do they behave as if pictures were alive, as if works of art had minds of their own, as if images had a power to influence human beings, demanding things from us, persuading, seducing, and leading us astray? Even more puzzling, why is it that the very people who express these attitudes and engage in this behavior will, when questioned, assure us that they know very well that pictures are not alive, that works of art do not have minds of their own, and that images are really quite powerless to do anything without the cooperation of their beholders? How is it, in other words, that people are able to maintain a “double consciousness” toward images, pictures, and representations in a variety of media, vacillating between magical beliefs and skeptical doubts, naive animism and hardheaded materialism, mystical and critical attitudes?4

The usual way of sorting out this kind of double consciousness is to attribute one side of it (generally the naive, magical, superstitious side) to someone else, and to claim the hardheaded, critical, and skeptical position as one’s own. There are many candidates for the “someone else” who believes that images are alive and want things: primitives, children, the masses, the illiterate, the uncritical, the illogical, the “Other.”5 Anthropologists have traditionally attributed these beliefs to the “savage mind,” art historians to the non-Western or premodern mind, psychologists to the neurotic or infantile mind, sociologists to the popular mind. At the same time, every anthropologist and art historian who has made this attribution has hesitated over it. Claude Lévi-Strauss makes it clear that the savage mind, whatever that is, has much to teach us about modern minds. And art historians such as David Freedberg and Hans Belting, who have pondered the magical character of images “before the era of art,” admit to some uncertainty about whether these naive beliefs are alive and well in the modern era.6

Let me put my cards on the table at the outset. I believe that magical attitudes toward images are just as powerful in the modern world as they were in so-called ages of faith. I also believe that the ages of faith were a bit more skeptical than we give them credit for. My argument here is that the double consciousness about images is a deep and abiding feature of human responses to representation. It is not something that we “get over” when we grow up, become modern, or acquire critical consciousness. At the same time, I would not want to suggest that attitudes toward images never change, or that there are no significant differences between cultures or historical or developmental stages. The specific expressions of this paradoxical double consciousness of images are amazingly various. They include such phenomena as popular and sophisticated beliefs about art, responses to religious icons by true believers and reflections by theologians, children’s (and parents’) behavior with dolls and toys, the feelings of nations and populations about cultural and political icons, reactions to technical advances in media and reproduction, and the circulation of archaic racial stereotypes. They also include the ineluctable tendency of criticism itself to pose as an iconoclastic practice, a labor of demystification and pedagogical exposure of false images. Critique-as-iconoclasm is, in my view, just as much a symptom of the life of images as its obverse, the naive faith in the inner life of works of art. My hope here is to explore a third way, suggested by Nietzsche’s strategy of “sounding the idols” with the “tuning fork” of critical or philosophical language.7 This would be a mode of criticism that did not dream of getting beyond images, beyond representation, of smashing the false images that bedevil us, or even of producing a definitive separation between true and false images. It would be a delicate critical practice that struck images with just enough force to make them resonate, but not so much as to smash them.

Roland Barthes put the problem very well when he noted that “general opinion . . . has a vague conception of the image as an area of resistance to meaning—this in the name of a certain mythical idea of Life: the image is re-presentation, which is to say ultimately resurrection.”8 When Barthes wrote this, he believed that semiotics, the “science of signs,” would conquer the image’s “resistance to meaning” and demystify the “mythical idea of Life” that makes representation seem like a kind of “resurrection.” Later, when he reflected on the problem of photography, and was faced with a photograph of his own mother in a winter garden as the “center” of the world’s “labyrinth of photographs,” he began to waver in his belief that critique could overcome the magic of the image: “When I confronted the Winter Garden Photograph I gave myself up to the Image, to the Image-Repertoire.”9 The punctum, or wound, left by a photograph always trumps its studium, the message or semiotic content that it discloses. A similar (and simpler) demonstration is offered by one of my art history colleagues: when students scoff at the idea of a magical relation between a picture and what it represents, ask them to take a photograph of their mother and cut out the eyes.10

Barthes’ most important observation is that the image’s resistance to meaning, its mythical, vitalistic status, is a “vague conception.” The whole purpose of this book is to make this vague conception as clear as possible, to analyze the ways in which images seem to come alive and want things. I put this as a question of desire rather than meaning or power, asking, what do images want? rather than what do images mean or do? The question of meaning has been thoroughly explored—one might say exhaustively—by hermeneutics and semiotics, with the result that every image theorist seems to find some residue or “surplus value” that goes beyond communication, signification, and persuasion. The model of the power of images has been ably explored by other scholars,11 but it seems to me that it does not quite capture the paradoxical double consciousness that I am after. We need to reckon with not just the meaning of images but their silence, their reticence, their wildness and nonsensical obduracy.12 We need to account for not just the power of images but their powerlessness, their impotence, their abjection. We need, in other words, to grasp both sides of the paradox of the image: that it is alive—but also dead; powerful—but also weak; meaningful—but also meaningless. The question of desire is ideally suited for this inquiry because it builds in at the outset a crucial ambiguity. To ask, what do pictures want? is not just to attribute to them life and power and desire, but also to raise the question of what it is they lack, what they do not possess, what cannot be attributed to them. To say, in other words, that pictures “want” life or power does not necessarily imply that they have life or power, or even that they are capable of wishing for it. It may simply be an admission that they lack something of this sort, that it is missing or (as we say) “wanting.”

It would be disingenuous, however, to deny that the question of what pictures want has overtones of animism, vitalism, and anthropomorphism, and that it leads us to consider cases in which images are treated as if they were living things. The concept of image-as-organism is, of course, “only” a metaphor, an analogy that must have some limits. David Freedberg has worried that it is “merely” a literary convention, a cliché or trope, and then expressed further anxieties over his own dismissive use of the wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Frontispiece

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: Images

- Part Two: Objects

- Part Three: Media

- Notes

- Index