eBook - ePub

The Analysis of the Self

A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Analysis of the Self

A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders

About this book

Psychoanalyst, teacher, and scholar, Heinz Kohut was one of the twentieth century's most important intellectuals. A rebel according to many mainstream psychoanalysts, Kohut challenged Freudian orthodoxy and the medical control of psychoanalysis in America. In his highly influential book The Analysis of the Self, Kohut established the industry standard of the treatment of personality disorders for a generation of analysts. This volume, best known for its groundbreaking analysis of narcissism, is essential reading for scholars and practitioners seeking to understand human personality in its many incarnations.

"Kohut has done for narcissism what the novelist Charles Dickens did for poverty in the nineteenth century. Everyone always knew that both existed and were a problem. . . . The undoubted originality is to have put it together in a form which carries appeal to action."—International Journal of Psychoanalysis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Analysis of the Self by Heinz Kohut in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTORY CONSIDERATIONS

The subject matter of this monograph is the study of certain transference or transferencelike phenomena in the psychoanalysis of narcissistic personalities, and of the analyst’s reactions to them, including his countertransferences. The primary focus of attention will not be on the schizophrenias and depressions, which are being treated by a number of psychoanalysts with special interest and talent in this field, or even on the milder or disguised forms of the psychoses, which are often referred to as borderline states, but on the contiguous, specific personality disturbances of lesser severity1 whose treatment constitutes a considerable part of present-day psychoanalytic practice. It is undoubtedly not easy at times to draw a line of demarcation between these conditions and the grave disorders to which they may appear to be related.

During temporary regressive swings in the course of the analysis of some of these patients symptoms might arise which could at first appear to be indicative of psychosis to those who are not familiar with the analysis of severe narcissistic personality disturbances. Yet, strangely, neither analyst nor patient tends to remain greatly alarmed by these temporary regressive experiences, even though their content (paranoid suspiciousness, for example; or delusional body sensations and profound shifts in self perception), if judged in isolation, would indeed justify the apprehension that a serious break with reality is imminent. But the total picture remains reassuring, in particular the fact that the event which precipitated the regression can usually be identified, and that the patient himself soon learns to look for the transference disturbance (a rebuff by the analyst, for example) when the regressive development is taking place. Once the analyst has become familiar with the patient—and in particular as soon as he has observed that one of the forms of narcissistic transference has spontaneously established itself—he will in general be able to reach the confident conclusion that the patient’s central disturbance is not a psychosis, and he will later maintain his conviction despite the occurrence of the aforementioned severely regressive but temporary phenomena in the course of analysis.

How is one to differentiate the psychopathology of the analyzable narcissistic personality disturbances from the psychoses and the borderline states? From what identifiable features of the patient’s behavior, or of his symptomatology, or of the analytic process can we derive the sense of relative security experienced by analysand and analyst, despite the presence of some seemingly ominous initial symptoms and of some apparently dangerous regressive swings during the analysis? I am discussing these questions with some reluctance at this point, not only because I trust that the present monograph in its entirety will gradually clarify the issue of differential diagnosis as theoretical understanding and clinical description become integrated in the mind of the reader, but especially in view of the fact that my approach to psychopathology is guided by a depth-psychological orientation which does not lead me toward looking at clinical phenomena according to the traditional medical model, i.e., as disease entities or pathological syndromes which are to be diagnosed and differentiated on the basis of behavioral criteria. For expository purposes, however, I shall now provide an anticipatory summary of the essentials of the pathology of these analyzable patients in dynamic-structural and genetic terms, and outline how the complaints of these individuals can be understood against the background of a metapsychological grasp of their personality disturbance.

These patients are suffering from specific disturbances in the realm of the self and of those archaic objects cathected with narcissistic libido (self-objects) which are still in intimate connection with the archaic self (i.e., objects which are not experienced as separate and independent from the self). Despite the fact that the fixation points of the central psychopathology of these cases are located at a rather early portion of the time axis of psychic development, it is important to emphasize not only the deficiencies of the psychic organization of these patients but also the assets.2

On the debit side we can say that these patients remained fixated on archaic grandiose self configurations and/or on archaic, overestimated, narcissistically cathected objects. The fact that these archaic configurations have not become integrated with the rest of the personality has two major consequences: (a) the adult personality and its mature functions are impoverished because they are deprived of the energies that are invested in the ancient structures; and/or (b) the adult, realistic activities of these patients are hampered by the breakthrough and intrusion of the archaic structures and of their archaic claims. The pathogenic effect of the investment of these archaic configurations is, in other words, in certain respects analogous to that exerted by the instinctual investment of unconscious repressed incestuous objects in the classical transference neuroses.

Disturbing as their psychopathology may be, it is important to realize that these patients have specific assets which differentiate them from the psychoses and borderline states. Unlike the patients who suffer from these latter disorders, patients with narcissistic personality disturbances have in essence attained a cohesive self and have constructed cohesive idealized archaic objects. And, unlike the conditions which prevail in the psychoses and borderline states, these patients are not seriously threatened by the possibility of an irreversible disintegration of the archaic self or of the narcissistically cathected archaic objects. In consequence of the attainment of these cohesive and stable psychic configurations these patients are able to establish specific, stable narcissistic transferences, which allow the therapeutic reactivation of the archaic structures without the danger of their fragmentation through further regression: they are thus analyzable. It may be added at this point that the spontaneous establishment of one of the stable narcissistic transferences is the best and most reliable diagnostic sign which differentiates these patients from psychotic or borderline cases, on the one hand, and from ordinary transference neuroses, on the other. The evaluation of a trial analysis is, in other words, of greater diagnostic and prognostic value than are conclusions derived from the scrutiny of behavioral manifestations and symptoms.

The following two typical dreams may provide us with an anticipatory understanding of the nature of the narcissistic transferences in the analysis of narcissistic personality disturbances, in particular of the fact that the specific psychopathology which is mobilized in the transference does not threaten the patient with psychotic disintegration.

Dream 1: The patient is in a rocket, circling the globe, faraway from the earth. He is, nevertheless, protected from an uncontrolled shooting off into space (psychosis) by the invisible, yet potently effective pull of the earth (the narcissistically cathected analyst, i.e., the narcissistic transference) in the center of his orbit.

Dream 2: The patient is on a swing, swinging forward and backward, higher and higher—yet there is never a serious danger of either the patient’s flying off, or of the swing uncontrolledly entering a full circle.

The first dream was dreamed almost identically by two patients who are not otherwise mentioned in the present work. The second dream was dreamed by Miss F. at a point when she felt anxious because of the stimulation by her intense archaic exhibitionism, which had become mobilized through the analytic work. The narcissistic transference protected the first two patients against the danger of potential permanent loss of the self (i.e., against schizophrenia), a danger which had arisen in consequence of the mobilization of archaic grandiose fantasies during therapy. In the second case the narcissistic transference protected the patient against a potentially dangerous overstimulation of the ego (a [hypo]manic state)—an overstimulation that had become a threat as a result of the mobilization of archaic exhibitionistic libido during analysis. The transference relationship to the analyst which is portrayed in these dreams is in all three instances an impersonal one (the impersonal pull of gravity; the patient being connected to the center of the swing)—a telling rendition of the narcissistic nature of the relationship.

Although the essential psychopathology of the narcissistic personality disturbances differs substantially from that of the psychoses, the study of the former contributes nevertheless to our understanding of the latter. The scrutiny of the specific, therapeutically controlled, limited swings toward the fragmentation of the self and the self-objects and the correlated quasi-psychotic phenomena which occur not infrequently in the course of the analysis of narcissistic personality disturbances offers, in particular, a promising access to the understanding of the psychoses—just as it may be fruitful to examine, in depth and in detail, the reaction of a few malignant or near-malignant cells within the healthy tissue of the organism, rather than to approach the problem of carcinoma by concentrating exclusively on patients who are dying of widespread metastases. Thus, while this monograph is not concerned with the psychoses and borderline states, I shall now make a few statements about the perspective gained on these severe forms of psychopathology in the light of the analyzable disorders with which I am dealing.

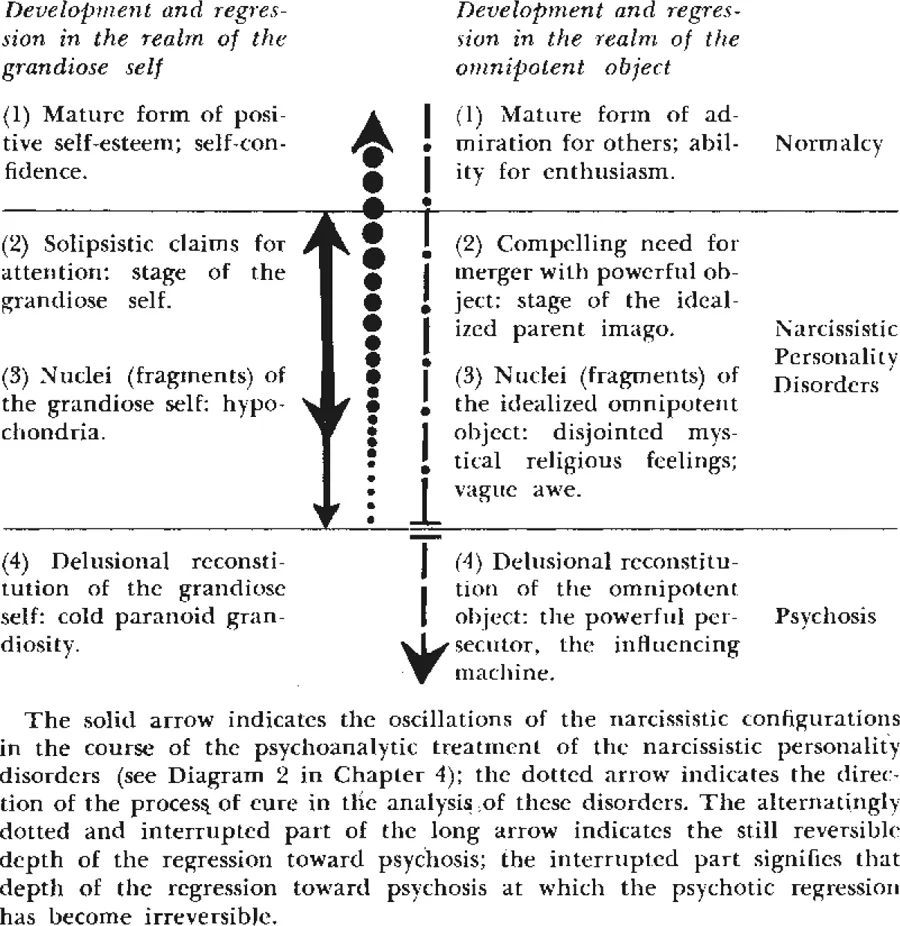

As is the case with the narcissistic personality disturbances, the psychotic disorders should not only (and perhaps not even predominantly) be examined in the light of tracing their regression from (a) object love via (b) narcissism to (c) autoerotic fragmentation and (d) secondary (delusional) restitution of reality. Instead it is especially fruitful to examine the psychopathology of the psychoses—in harmony with the assumption that narcissism follows an independent line of development—in the light of tracing their regression along a partly different path which leads through the following way stations: (a) the disintegration of higher forms of narcissism; (b) the regression to archaic narcissistic positions; (c) the breakdown of the archaic narcissistic positions (including the loss of the narcissistically cathected archaic objects), thus the fragmentation of self and archaic self-objects; and (d) the secondary (restitutive) resurrection of the archaic self and of the archaic narcissistic objects in a manifestly psychotic form.3

The last-mentioned stage is only fleetingly encountered during the analysis of narcissistic personality disturbances; but the relevant ephemeral phenomena permit the observation of details which are hidden in the rigidly established pathological positions in the psychoses. It is, for example, particularly instructive to compare the cohesive archaic narcissistic configurations (the grandiose self and the idealized parent imago) (a) with their regressively altered forms as they are moving toward fragmentation, and (b) with their restitutive counterparts when the rigid and chronic condition of a more or less overt psychosis has established itself.

Details of some of the patient’s experience of hypercathected disconnected fragments of the body, of the mind, and of physical and mental functions can, for example, be observed during the temporary therapeutic regressions from the cohesively cathected grandiose self, and from the idealized parent imago, which may not be accessible in the corresponding regressions in the psychoses where the communicative capacity becomes severely disturbed and self-observation is either diminished or grossly distorted. Through the mild regressive oscillations, however, which occur during the analysis of narcissistic personality disturbances We gain access to many subtleties of these regressive transformations. We can see in detail, and study comparatively leisurely, the various disturbances in body sensation and self perception, the degeneration of language, the concretization of thought, and the splitting off of formerly synthetically cooperating thinking processes, as well as the observing ego’s reaction to the temporary fragmentation of the narcissistic configurations (see Diagram 2 in Chapter 4 for a survey of some of the oscillations which occur during the analysis of these disorders). And it is especially fruitful to compare the relatively healthy archaic narcissistic configurations (the grandiose self; the idealized parent imago) with their psychotic counterparts (delusional grandiosity; the “influencing machine” [Tausk, 1919]).

The decisive differentiating features between the psychoses and borderline states, on the one hand, and analyzable cases of narcissistic personality disturbance, on the other, are the following: (1) the former tend toward the chronic abandonment of the cohesive narcissistic configurations and toward their replacement (in order to escape from the intolerable state of fragmentation and loss of archaic narcissistic objects) by delusions; (2) the latter show only minor and temporary oscillations, usually toward partial fragmentation, with at most a hint of a fleeting restitutive delusion. It is very valuable for our theoretical understanding of both the psychoses and the narcissistic personality disturbances to study the similarities and differences between the relatively healthy archaic grandiosity, which the psyche is able to maintain in the latter disorders, and the cold and haughty psychotic delusions of grandeur, which occur in the former; and to compare in the same way the relatively healthy elaboration of a narcissistically cathected omnipotent and omniscient, admired and idealized, emotionally sustaining parent imago in the transferences formed by patients with narcissistic personality disturbance with the all-powerful persecutor and manipulator of the self in the psychoses: the influencing machine whose omnipotence and omniscience have become cold, unempathic, and nonhumanly evil. Last but not least, the examination of the prepsychotic personality from the point of View of the vulnerability of its higher forms of narcissism (rather than only from the point of view of the fragility of its mature relationships to loved objects) can contribute greatly to the understanding of the psychoses and borderline states and will, for example, explain the following two typical features: (1) the precipitating events which usher in the decisive first steps of the regressive movements lie frequently in the area of narcissistic injury rather than in that of object love; and (2) even in some severe psychotic disorders, object love may remain relatively undisturbed while a profound disturbance in the realm of narcissism is never absent.

The following diagram is intended to provide a preliminary outline of the developmental steps of the two major narcissistic configurations and, simultaneously, of their counterparts, i.e., the waystations of the regressive transformation of these configurations in (a) the narcissistic personality disorders and (b) the (schizophrenic-paranoid) psychoses and borderline states.

DIAGRAM 1

The regressive psychic structures, the patient’s perception of them, and his relationship to them, may become sexualized both in the psychoses and in the narcissistic personality disorders. In the psychoses the sexualization may involve not only the archaic grandiose self and the idealized parent imago, as these structures are fleetingly cathected before they are destroyed (autoerotic fragmentation), but also the restitutively built-up delusional replicas of these structures which form the content of the overt psychosis. It would be an intriguing task to compare the sexualizations in the psychoses, which were first described and metapsychologically elucidated by Freud (1911), with the sexualizations of the various forms of the narcissistic transferences which occur not infrequently in the analysis of narcissistic personality disturbance. The sexualized versions of the narcissistic transference are encountered either (a) early in the analysis, usually as a direct continuation of perverse trends which were already present before the treatment (see here especially the extensive discussion of the sexualization of the idealized parent imago and of the alter-ego or twinship variant of the grandiose self in the case of Mr. A. in Chapter 3); or (b) fleetingly during the exacerbations of the termination phase in the analysis of narcissistic personality disorders (see Chapter 7).

This is not the place for a comprehensive review of the psychoanalytic theory of the formation of hallucinations and delusions in the psychoses. Within the framework of the present considerations, however, it should be stressed that their establishment follows the disintegration of the grandiose self and of the idealized parent imago. In the psychoses these structures are destroyed, but their disconnected fragments are secondarily reorganized, rearranged into delusions (see Tausk, 1919; Ophuijsen, 1920), and then rationalized through the efforts of the remaining integrative functions of the psyche. As a result of the most severe regressive swings in the analysis of narcissistic personality disorders we occasionally encounter phenomena which resemble the delusions and hallucinations of the psychotic. Mr. E., for example, under the stress of an impending separation from the analyst early in treatment, felt temporarily that his face had become the face of his mother. In contrast to the psychoses, however, these hallucinations and delusions are not due to the elaboration of stable pathological structures which the patient erects in order to escape from the unbearable experience of the protracted fragmentation of his body-mind-self. They occur fleetingly at the moment of a beginning partial and temporary disintegration of the narcissistic structures, in response to specific disturbances of the specific narcissistic transference which has become established in therapy.

The evaluation of the role of specific environmental factors (the personality of the parents, for example; certain traumatic external events) in the genesis of the developmental arrest, or of the specific fixations and regression propensities which constitute the core of the narcissistic personality disturbance, will be undertaken later in this study. A brief, genetically oriented remark, however, may at this point help to solidify the conceptual basis of the differentiation between the psychoses and the borderline states, on the one hand, and the narcissistic personality disturbances, on the other. From the genetic point of view one is led to assume that in the psychoses the personality of the parents (and a number of other environmental circumstances) collaborated with inherited factors to prevent the formation of a nuclear cohesive self and of a nuclear idealized self-object at the appropriate age. The narcissistic structures which are built up at a later age must, therefore, be visualized as hollow and thus as brittle and fragile. Given these conditions (i.e., given a psychosisprone personality), narcissistic in juries may usher in a regressive movement which tends to go beyond the stage of archaic narcissism (beyond the archaic forms of the cohesive grandiose self or of the cohesive idealized parent imago) and to lead to the stage of (autoerotic) fragmentation.

Two elaborations of the preceding statements regarding (a) the dynamic effect, and (b) the genetic background of the prepsychotic (or rather the psychosis-prone) personality will be inserted at this point. The first one is predominantly of clinical importance, the second one is of greater theoretical interest.

The first modification of the dynamic consequences of a specific weakness in the basic narciss...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1. Introductory Considerations

- Part I. The Therapeutic Activation of the Omnipotent Object

- Part II. The Therapeutic Activation of the Grandiose Self

- Part III. Clinical and Technical Problems in the Narcissistic Transferences

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Concordance of Cases

- Index