- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In literary studies today, debates about the purpose of literary criticism and about the place of formalism within it continue to simmer across periods and approaches. Anna Kornbluh contributes to—and substantially shifts—that conversation in The Order of Forms by offering an exciting new category, political formalism, which she articulates through the co-emergence of aesthetic and mathematical formalisms in the nineteenth century. Within this framework, criticism can be understood as more affirmative and constructive, articulating commitments to aesthetic expression and social collectivity.

Kornbluh offers a powerful argument that political formalism, by valuing forms of sociability like the city and the state in and of themselves, provides a better understanding of literary form and its political possibilities than approaches that view form as a constraint. To make this argument, she takes up the case of literary realism, showing how novels by Dickens, Brontë, Hardy, and Carroll engage mathematical formalism as part of their political imagining. Realism, she shows, is best understood as an exercise in social modeling—more like formalist mathematics than social documentation. By modeling society, the realist novel focuses on what it considers the most elementary features of social relations and generates unique political insights. Proposing both this new theory of realism and the idea of political formalism, this inspired, eye-opening book will have far-reaching implications in literary studies.

Kornbluh offers a powerful argument that political formalism, by valuing forms of sociability like the city and the state in and of themselves, provides a better understanding of literary form and its political possibilities than approaches that view form as a constraint. To make this argument, she takes up the case of literary realism, showing how novels by Dickens, Brontë, Hardy, and Carroll engage mathematical formalism as part of their political imagining. Realism, she shows, is best understood as an exercise in social modeling—more like formalist mathematics than social documentation. By modeling society, the realist novel focuses on what it considers the most elementary features of social relations and generates unique political insights. Proposing both this new theory of realism and the idea of political formalism, this inspired, eye-opening book will have far-reaching implications in literary studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Order of Forms by Anna Kornbluh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2019Print ISBN

9780226653341, 9780226653204eBook ISBN

97802266534881

The Realist Blueprint: For a Formalist Theory of Literary Realism

What does realism build? For its earliest, most preeminent theorist, realism builds houses. Across his theory and his art, Henry James figures realism’s craft and construction of vibrant spaces with architecture.1 As he put it in one of many such pronouncements, “A great building is the greatest conceivable work of art,” and thus the writer as artist “has verily to build, is committed to architecture, to construction at any cost; to driving in deep his vertical supports and laying across and firmly fixing his horizontal, his resting pieces—at the risk of no matter what vibration from the tap of his master-hammer.”2 James’s famous image of “the house of fiction” conjures a three-dimensional structure from which multiple and divergent points of view cast their gaze, but beyond this familiar spatialization of perspective, his repeated architectural language of engineered building gives shape to an account of how realist form works to produce an integrated world. For James, realism works architecturally because it projects coherent spaces independent of preexisting spaces but dependent upon laws of composition—because, in short, it evinces a formalistic regard for world-making. The Order of Forms advocates for such a regard, developing a notion of political formalism from out of the methods and innovations of mathematical formalism and aesthetic formalism. In the introduction, I have defined political formalism as esteem for the arts of social building, and the bulk of this book engages in formalist readings of major realist novels, for which this prefatory chapter necessarily establishes the conditions of possibility. Framing its affinities with architecture (the modeling of social space) and with mathematics (the modeling of possible space), I argue that realism is a speculative, abstract, nonmimetic form amenable to formalist address.

Jamesian Elevations

James provides great impetus for this speculative foray, since he articulated an imperative for theory, lamenting that even those few novelists he admired “had no air of having a theory, a conviction, a consciousness of itself behind it,”3 and since his theory emerged in the dynamic interplay of his literary criticism and his literary form. Many of James’s theoretical designations of the novel—“point of view,” “the scenic method,” “interior,” and so on—function, as Dorothy Hale notes, to “spatialize writing.”4 Many of his signature stylistic gestures function similarly: his incorporation of the collective space of the theater into his fiction as what David Kurnick calls a “externalizing, centrifugal social will”;5 his frequent domestic settings; his use of metonymy to precipitate transitions in the flowing stream of consciousness; his representation of consciousness “spatially as being situated not inside the single self but outside, between persons”;6 and his incredible drive toward solidifying prose syntax, making paragraphs and pages into blocks and bricks, a masonry of densification that Seymour Chatman calls “nominalization.”7 So many elements of his form engage tropics of space and structuration, and Jamesian climaxes are perhaps the most pointed such element, pitching literary spaces in intensely architectural code. In what is only the most succinct climax, from the acutely constructive The Portrait of a Lady, Isabelle Archer’s grim recognition of her plot is rendered thusly: “The truth of things, their mutual relations, their meaning, and for the most part their horror, rose before her with a kind of architectural vastness.”8 More roomily, The Wings of the Dove depicts Milly Theale’s scheme to match being schemed as the militant occupation of a Venetian palace:

She looked over the place, the storey above the apartments in which she had received him, the sala corresponding to the sala below and fronting the great canal with its gothic arches. The casements between the arches were open, the ledge of the balcony broad, the sweep of the canal, so overhung, admirable, and the flutter toward them of the loose white curtain an invitation to she scarce could have said what. But there was no mystery after a moment; she had never felt so invited to anything as to make that, and that only, just where she was, her adventure. It would be—to this it kept coming back—the adventure of not stirring. “I go about just here.”9

Most voluminously The Golden Bowl magisterially confabulates Maggie’s dilated anagnorisis, spatializing the time of realization into an exotic locale:

This situation had been occupying, for months and months, the very centre of the garden of her life, but it had reared itself there like some strange, tall tower of ivory, or perhaps rather some wonderful, beautiful, but outlandish pagoda, a structure plated with hard, bright porcelain, coloured and figured and adorned, at the overhanging eaves, with silver bells that tinkled, ever so charmingly, when stirred by chance airs.10

In each of these passages, and in so many others, James’s heroines discover the structures in which they are determinatively enclosed, and this very structural literacy facilitates their ultimate acts of freedom. His novels deploy architecture as an exotic figure for a fugitive uneclipsed sphere of social relations: architecture expresses comprehending sociality in all its banality and dimensionality.

Where the novels install this commanding trope of social volume, the Prefaces even more emphatically appraise it. Thus the image of the “house of fiction” circulates widely, yet inspires too ready domestication of its floor plan, too quick flattening of its elevation, too many culturalist studies of interior design. In fact, when the Preface to The Portrait of a Lady drafts that house, it arrays curiously conflicting figures: although James frequently invokes solidities like “bricks,” “buildings,” “cornerstones,” and “foundations,” he also accentuates the incommensurability between ordinary employments of matter and mortar and his extraordinary assemblages:

The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million—a number of possible windows not to be reckoned, rather; every one of which has been pierced, or is still pierceable, in its vast front, by the need of the individual vision and by the pressure of the individual will. These apertures, of dissimilar shape and size, hang so, all together, over the human scene that we might have expected of them a greater sameness of report than we find. They are but windows at the best, mere holes in a dead wall, disconnected, perched aloft; they are not hinged doors opening straight upon life.11

Not even the Pritzker Prize–winning conceptual architect Zaha Hadid could have built such a house, with its unreckonable number of pierceable, disparate windows. These infinite windows “are not hinged doors opening straight,” permitting passage from exterior to interior or from fiction to fact; they are not even portals of illumination, but chimeric reverberations, penetrable fenestrations, holes within holes, queer openings casting an ontological paradox: since “dead wall” is the architectural term for a wall without windows, the fabrication here cleaves windows in a place without windows, lacunae unto their own nonexistence. The planar distortions and dimensional disjunctions of the house of fiction exceed what already exists, spatializing openings to the inexistent. James repeatedly associates architecture with such excesses—the innumerable, the infinite—outlining a paradoxical science of audaciously building impossible buildings.

Yet, for all the inventive intensity of Jamesian architecture, his edifices nonetheless hew to firm standards of integrity, to what he called “the principle of cohesion.”12 Employing architectural metaphors to convey the “proper fusions” that scaffold his visions, James labors under the imperative of precise engineering:

For erecting on such a plot of ground the neat and careful and proportioned pile of bricks that arches over it and was thus to form, constructionally speaking, a literary monument . . . : a structure reared with an “architectural” competence . . . I should clearly have to pile brick upon brick . . . , I would leave no pretext for saying that anything is out of line, scale or perspective. I would build large—in fine embossed vaults and painted arches, as who should say, and yet never let it appear that the chequered pavement, the ground under the reader’s feet, fails to stretch at every point to the base of the walls.13

When novelists fail, in James’s estimation, as in the cases of Eliot’s discursivity without dramatic intensity, Dickens’s action without character density, Trollope’s distension without limit, or Turgenev’s simple “want of architecture,” the failure rests in this dimension of architectural integrity—of proportioning and intercalation. Thus his renderings for the house of fiction famously tighten such “large loose baggy monsters” into crystalline design. His theory of the novel repeatedly advocates for “fusion”—the interrelation of parts (character, incident, description) but also the ultimate inseparability of “substance and form.” The precisely built work is one in which it is “impossible to say . . . where one of these elements ends and the other begins” and one is “unable . . . to mark any such joint or seam.”14 James prizes structural integrity above all else; as he puts it, “The continuity of things is the whole matter.”15

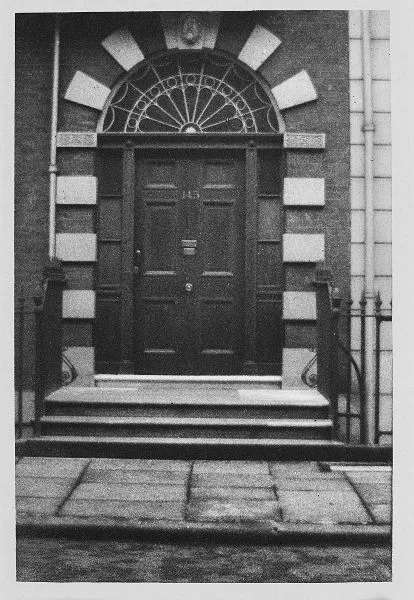

The preeminence of architectural tropes for James is vividly legible in that ambivalent edification of his corpus, the New York Edition. For this undertaking, James created illustrations that reinforce the powerful associations of his form and architecture. Originally envisioning a “scene, object, or locality” to be printed with each volume of fictional houses, James commissioned photographs that, in a fashion deeply reminiscent of the constructivism in Talbot’s invention, prioritize the spatial dimensions of scenes and locality. The photographs display an almost singular focus on architecture: twenty-three of the twenty-four plates show structures, and even the sole exception—a portrait of the artist in ninety-degree profile—is arguably some kind of external section drawing. Colonnades, arches, bridges, gates, courtyards, grand halls, cathedrals, palaces, plazas, shops, neighboring clusters, houses, and doors, doors, doors—the photographs offer so many forms of open enclosures, of publics spectacular and mundane, of facades and their permeations, situations, relations. In the Prefaces to the New York Edition, James underscored the imaginary character of these spaces, prescribing that each photograph should “speak for its odd or interesting self”16 rather than speak for a definite context or for the story; he similarly insisted that the settings of his works were themselves imaginary, a dislocation from recognizable geography, in the grand tradition of the decided fictionality of Trollope’s Barsetshire, Hardy’s Wessex, Eliot’s provinces.17 Richard Blackmur notes of the commissioning process that James was “insistent that no illustration to a book of his should have any direct bearing upon it,”18 and the photographer Alvin Coburn’s expansive use of filters and soft grain techniques enhance this effect of floating—dislocating the scenes from even themselves. Taken together with the pervasive architectural language of the Prefaces, the photographs offer a sister foyer for the fictions, firmly articulating the work of novelistic realism as that mathematically formal myriad production of unindexable space.

FIGURE 3. Alvin Langdon Coburn, The Doctor’s Door (early twentieth century). Frontispiece to The Novels and Tales of Henry James (New York Edition), vol. 19. Photograph: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Spacing Realism

Jamesian architecture invites us to think form spatially, and to behold architecture as the art of forming spaces. In this it echoes the spatial imaginary of projective mathematics, while it also anticipates both the intermittent spatialisms ensuing in the history of literary criticism and the speculative theorizations in the history of architecture. Eons before the word “plot” takes on literary connotation, the OED indicates, it denotes first and foremost “a piece of ground” and secondly “a map, a plan, a scheme.” These spatial grounds of the “plan or scheme of a literary work” suggest how much the plottedness ontologically comprises spatial projections, symbolizations of possible configurations of space.19 Thus Michel de Certeau finds all narratives are intrinsically spatial: “They traverse and organize places; they select and link them together; they make sentences and itineraries out of them. They are spatial trajectories.”20

I take inspiration for attending to literary architecturalist modeling from the mathematical radicalizations of the concept of model, the inscription of that which is not strictly available to experience. Wonderfully, the first use of “space” as a term in literary analysis in fact derives from mathematics. Mikhail Bakhtin professed to “borrow” from “mathematics” the concept of the “chronotope”—the unity of space and time—“almost as a metaphor (almost but not entirely).”21 Just as non-Euclidean geometry raised the prospect that different orders of the universe can be defined by different space-time relations, Bakhtin extends his borrowing to argue that different literary genres can be defined by different chronotopes.22 Nevertheless, Bakhtin was only so mathematical; he staked out the unity of time-space in line with formalist mathematics’ radicalization of space, but he ultimately prioritized the temporal axis, emphasizing that plot-qua-action-transpiring-in-time is what founds the design of the narrative space.23 Joseph Frank introduced alternative qualifications to such temporal paradigms with his now famous argument that modernist literature distinctly “intend[s] the reader to apprehend their work spatially, in a moment of time, rather than as a sequence.”24 In making this intervention, Frank emphatically situated spatial form in a modernism he found absolutely disjoint from realism—a disjuncture that remains sacrosanct. Yet James’s theories, and indeed nineteenth-century fictions themselves, underline that realism too may be considered spatially.

Such consideration has been actualized only recently, in Alex Woloch’s The One vs. the Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist.25 Woloch defines the novel as the asymmetric distribution of character space that models the asymmetric distribution of resources under capitalism, and goes on to define character space as “the intersection of an implied human personality . . . with the definitively circumscribed form of a narrative,”26 the set of which spaces and their arrangement comprising in turn “the character-system.”27 Seeing the complex characterization of realism in spatial terms can in turn prompt investigations of the spatiality of other modal features of realism, such as its high degree of plottedness or its frequent omniscience.

The much lauded spatial turn of modernism appears, by the lights of these intermittent spatialisms, not as the repudiation of a realism more temporally obsessed (as evidenced in linear narrative, unfolding history), but as the prismatic extraction of realism’s already extrusive projections of space in the abstract. After all, as Roman Jakobson inferred,28 realism is decidedly spatial in its prioritization o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction The Order of Forms: Mathematic, Aesthetic, and Political Formalisms

- 1 The Realist Blueprint: For a Formalist Theory of Literary Realism

- 2 The Set Theory of Wuthering Heights: Realism, Antagonism, and the Infinities of Social Space

- 3 The Limits of Bleak House

- 4 Symbolic Logic on the Social Plane of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- 5 Obscure Forms: The Social Geometry of Jude the Obscure

- 6 States of Psychoanalysis: Formalization and the Space of the Political

- Conclusion Sustaining Forms

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index