eBook - ePub

Philanthropy in Democratic Societies

History, Institutions, Values

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Philanthropy in Democratic Societies

History, Institutions, Values

About this book

Philanthropy is everywhere. In 2013, in the United States alone, some $330 billion was recorded in giving, from large donations by the wealthy all the way down to informal giving circles. We tend to think of philanthropy as unequivocally good, but as the contributors to this book show, philanthropy is also an exercise of power. And like all forms of power, especially in a democratic society, it deserves scrutiny. Yet it rarely has been given serious attention. This book fills that gap, bringing together expert philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, historians, and legal scholars to ask fundamental and pressing questions about philanthropy's role in democratic societies.

The contributors balance empirical and normative approaches, exploring both the roles philanthropy has actually played in societies and the roles it should play. They ask a multitude of questions: When is philanthropy good or bad for democracy? How does, and should, philanthropic power interact with expectations of equal citizenship and democratic political voice? What makes the exercise of philanthropic power legitimate? What forms of private activity in the public interest should democracy promote, and what forms should it resist? Examining these and many other topics, the contributors offer a vital assessment of philanthropy at a time when its power to affect public outcomes has never been greater.

The contributors balance empirical and normative approaches, exploring both the roles philanthropy has actually played in societies and the roles it should play. They ask a multitude of questions: When is philanthropy good or bad for democracy? How does, and should, philanthropic power interact with expectations of equal citizenship and democratic political voice? What makes the exercise of philanthropic power legitimate? What forms of private activity in the public interest should democracy promote, and what forms should it resist? Examining these and many other topics, the contributors offer a vital assessment of philanthropy at a time when its power to affect public outcomes has never been greater.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philanthropy in Democratic Societies by Rob Reich, Chiara Cordelli, Lucy Bernholz, Rob Reich,Chiara Cordelli,Lucy Bernholz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Nonprofit Organizations & Charities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226335643, 9780226335506eBook ISBN

9780226335780PART I

Origins

We begin this volume with a part on origins to demonstrate persistent, fundamental tensions between philanthropy and democracy. As this book goes to press, new forms of philanthropy and civic action are front-page news. New forms of enterprise, such as the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, are pushing on a century of institutional practice. Collectively we wonder at the power of mobile phone–based organizing, online campaigns, and new forms of digital association. We gape at the gadgetry but are more concerned with the ways core values of democratic participation are being simultaneously amplified and constrained in the digital activism all around us. How do we define and evaluate private action for public benefit in the digital age? Satisfactory answers to this question depend heavily on its historical precedents.

Over the course of two hundred years, American citizens and their representatives have struggled to define the proper bounds of state (government) action, while questioning which forms of private (corporate) action should be allowed or promoted. This problem, separating private activity from state action, has persisted, taking many different forms from the nineteenth century to the present. Jonathan Levy opens the volume with a look at a transitional moment in answering these questions, an era that endowed us with the basic institutional structures we rely on today.

As we move through time to the present day we see the weathering of these institutions through economic, social, and ideological battles. Olivier Zunz shows how philanthropy weaves throughout a century of social and political movements, rarely stepping to the fore of scholars’ attention yet always present, especially when he casts the light on the steady, small acts of millions of people. Zunz presents the study of philanthropy as a way of examining these tensions—between state roles, commercial activities, and citizen action—as they play out across communities and time.

A distinctive corporate form of American philanthropy is the general purpose private foundation, an entity created in the early twentieth century by the likes of Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller in the foundations that still bear their names. What’s often forgotten today, however, is the deep resistance to and democratic skepticism of the private foundation that attended their creation. Rob Reich’s chapter recovers a bit of this history in his examination of what role the plutocratic voice of a philanthropic foundation should have in a democratic society.

Two hundred years of American history include ongoing efforts to delineate the boundaries of corporate activity. Today, the distinction of not-for-profit and for-profit corporations seems clear (at least legally), but history shows that these terms and boundaries have never been fixed. Institutions first crafted in the age of the telegraph are being reshaped in the wireless age. Time moves through those boundaries, and we find ourselves in moments when the existing institutional lines don’t seem to fit with contemporary needs or possibilities. This is where we are today, at a moment when the boundaries of public and private have been blurred by many forces.

We understand philanthropy’s history as encompassing not only the history of giving but also the broader history of political economy, state action, institutional form, and conceptions of private morality. This part, and the volume as a whole, focuses on the changing nature of philanthropic institutions, how we have legally constrained private actions for public benefit, and how those boundaries represent broader political, social, and intellectual values.

ONE

Altruism and the Origins of Nonprofit Philanthropy

Jonathan Levy

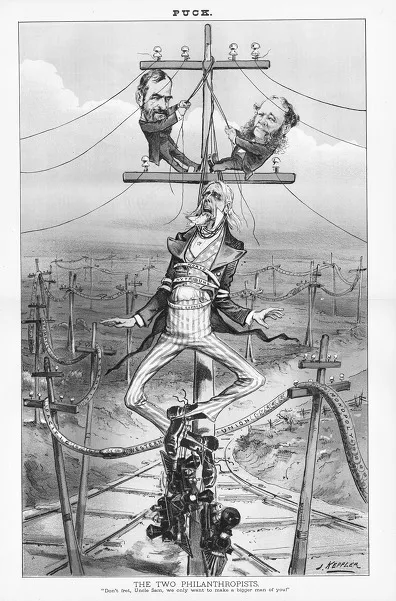

From left to right in figure 1.1, Joseph Keppler’s Puck Magazine political cartoon “The Two Philanthropists,” are Jay Gould, the great New York City financier, and William Vanderbilt, the son of recently deceased railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt. At the time, Gould was competing with Vanderbilt for financial command over the corporation that controlled 90 percent of U.S. telegraphic service, the Western Union Telegraph Company. The Telegraph Act of 1866 had granted the U.S. government authority to purchase Western Union, to transform a private telecommunications network into effectively a public utility. Gould and Vanderbilt were bidding up the stock price, in competition with one another but with the consequence, intended or not, of forestalling an ever more expensive government purchase. But what does any of that have to do with philanthropy?

1.1. Joseph Keppler, “The Two Philanthropists,” Puck, February 23, 1881.

The question is not so easy to answer because at that time the meaning and institutional location associated with philanthropy across the twentieth century was not yet fixed. In the twentieth century, “philanthropy” would come to mean the private redistribution of wealth—usually first earned through private capitalist profit-making—through a “nonprofit sector.” But that was not yet the case when Keppler drew “The Two Philanthropists” in 1881.

Philanthropy, perhaps by definition, is a form of private action. Yet, historically philanthropy has always been clothed with a public character, even if, over time, the clothes have changed. Ever since the permanent introduction of a federal income tax in 1913, tax exemption has made American philanthropy inescapably public. But before that, what originally made philanthropy public was its institutional organization by and through state-chartered corporations. If there is one continuity to the history of American philanthropy, it is that, from the first, it has been a corporate enterprise.

Gould and Vanderbilt claimed that their corporation, the Western Union Telegraph Company, benefited the public. They insisted that they were not engaging in financial buccaneering but instead laying the nation’s first telegraphic network. The public would benefit most if that communications infrastructure remained under private charge rather than being ceded to the U.S. federal government. Keppler’s caption mocked them: “Don’t fret, Uncle Sam, We only want to make a bigger man of you!” In this, Keppler satirized one kind of philanthropic pretension. That is, the pretension that the outcome of private corporate profit-making was of great, even “philanthropic” benefit to the public—a familiar sentiment in the age not only of Gould, but also of Google.

In nineteenth-century America, however, that sentiment had a specific valence. The first generation of Americans, experimenting with republican government, had created one, mixed public/private corporate form, what might be called the republican corporation. While the propertied basis of the republican corporation was private, state legislatures chartered corporations on a discretionary basis, by up or down vote, to perform “public purposes.” For a corporation was a “grant” or “concession” of popular sovereignty. Various public purposes were almost always construed as “benevolent” in character, benevolence being a concept that mixed, rather than distinguished, between private action and public purpose. To ensure these purposes, the private actions of corporations were constrained by the language of their state-granted charters, including the 1851 corporate charter New York State granted to what would become the Western Union Telegraph Company. It was this legacy—that all corporations, ranging from charities to universities to joint-stock companies—were mixed public/private entities, chartered for benevolent public purposes, that Gould sought to draw from to stave off a government takeover of Western Union.

Keppler believed Gould’s appropriation of the republican legacy was cynical, and it was. “The Two Philanthropists” depicts the death throes of the old republican corporate order. And yet the cartoon, in subtle ways, says more. The American republic was by then a liberal capitalist democracy. Corporations, agents of that change, transformed themselves accordingly. “The Two Philanthropists” depicts not only the collapse of the old order. By another reading, it also uncannily deciphers the coming of a new corporate universe, the universe in which the modern relationship between philanthropy and democracy—at stake in every chapter to come in this book—would unfold.

Rather than consisting of one, republican corporate form, this was a private corporate universe of liberal corporations, for profit and nonprofit, a corporate universe, aspirationally, of moral and institutional binaries. In it, only private nonprofit corporations—not states or for-profit corporations like the Western Union—became appropriate vehicles of “philanthropy.” Indeed, not until the 1870s was the very language and classification of “nonprofit” present. Only then did philanthropy begin to acquire one specific meaning—the private redistribution of wealth, often first earned through profit-making, through “nonprofit” institutional forms.

By the new criterion, Gould could not even pretend to be a philanthropist. (The Vanderbilts at least had founded Vanderbilt University in 1873. There is no such thing as Gould University.) Gould gave little of his wealth away, although his daughter, after inheriting his fortune, would. His greatest contribution to the history of philanthropy, in this new key, was probably the inclusion of his friend Russell Sage in many of his deals. Gould finally did take control of Western Union in 1881 and proceeded to place Sage on the board. Sage made a lot of money this way, but he too gave little of it away. Through his widow, however, his wealth would ultimately come to rest in the Russell Sage Foundation (1907), the first “general-purpose foundation.” This and later general-purpose foundations afforded wide donor discretion, and the structure became modern philanthropy’s most dominant nonprofit institutional form.

A lot had to change in the final decades of the nineteenth century, as this chapter demonstrates, for this dominance to occur. The passing of state-level general incorporation laws in the middle decades of that century first liberated access to incorporation. No longer a discretionary grant of sovereignty, a corporate charter became a free entitlement of citizenship. Rather than public purpose, state legislatures placed new stress on the private motivation to incorporate. It was the new accent on private motive that led to the creation of the for-profit/nonprofit binary. Critical was a new moral vocabulary, the gift of the English evolutionary thinker Herbert Spencer, of “egoism” and “altruism.” The liberal keyword altruism, displacing the old republican keyword of benevolence, was as new to the latter half of the nineteenth century as the nonprofit corporation. The “discovery” of altruism, a private, purely other-regarding value, helped lend much-needed credit to philanthropy’s new corporate home.

This chapter thus explores the late nineteenth-century historical connection between a moral idea, altruism, and the origins of a critical philanthropic institution, the nonprofit corporation. At stake, amidst competing efforts to mend the social cleavages and economic inequalities of industrial capitalism, was the relationship between public and private action, a new corporate ordering of the production and redistribution of wealth, and arguments that continue today—and in this volume—about the legitimacy of corporate philanthropy in a democracy.

On the question of democratic legitimacy, Keppler’s “The Two Philanthropists” had its say as well. The cartoon was an early, soon-to-be familiar polemic against the private philanthropic redistribution of wealth—a critique of Gilded Age America’s financial excess. In the first decades of the twentieth century, they would become Progressive political critiques of the great accumulations of philanthropic wealth in general-purpose foundations like the Russell Sage Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation (1911), or the Rockefeller Foundation (1913). But on closer examination, “The Two Philanthropists” also depicts a binary. The cartoon is divided in half, cut down the middle by the largest telegraph pole, with two railroad tracks flowing into one. Gould and Vanderbilt contest one another but pull on the same wires, strangling an emaciated body politic—a private stranglehold, so to speak, on the public good. Keppler not only mocked philanthropic pretensions. He criticized, prophetically, one conception of private morality, with its related institutional forms, that obfuscates the realities of corporate power. That conception is a moral universe of binaries, a contest between the private motives of egoism and altruism, institutionally residing in for-profit corporations and nonprofit corporations sharply distinguished from one another, but in the end two sides of the same corporate coin. This corporate universe, Keppler warned, might well leave but little room for the public good.

The Republican Corporation

In 1832 Joseph Angell and Samuel Ames published the first American legal treatise on corporations, Treatise on the Law of Private Corporations Aggregate.1 In it, there is no mention of a nonprofit corporation. Having evolved in the decades after the American Revolution, the “private corporation aggregate” was a specifically American corporate form, of mixed public/private character. Only later, in the decades after the Civil War, would the private corporation aggregate—the republican corporation—split into two liberal corporations, for-profit and nonprofit. Without first grasping the nature of the republican corporation, including its historical roots and working logic, it is impossible to understand the subsequent novelty and significance of nonprofit corporate philanthropy. This history of corporate form also provides a window onto shifting definitions of public and private action, including their disentanglement across the nineteenth century.

Angell and Ames cited the prior English classificatory scheme. For centuries in England, there were corporations “sole” and corporations “aggregate.” Corporations sole consisted of one person, namely the sovereign (the king is dead, long live the king!) or individuals holding religious offices, like bishops.2 Corporations aggregate, associations of two or more persons, consisted of two types: “lay” and “ecclesiastical.” In America, after the Revolution, both corporations sole and corporations aggregate ecclesiastical were no more. All that remained were corporations aggregate lay. Within lay, Angell and Ames explained, once more there were two forms, “civil” and “eleemosynary.” Corporations aggregate lay civil consisted of both municipalities (future cities) and joint-stock trading companies (future for-profit corporations). Corporations aggregate lay eleemosynary performed, broadly speaking, charitable tasks, including purposes proscribed in the preamble to the Elizabethan Charitable Uses Act of 1601, such as the “maintenance of sicke” and “education.” The corporation aggregate lay eleemosynary would appear to be the most obvious candidate for the direct forebear of the American nonprofit corporation. But that was not the case.

Instead, Americans combined civil and eleemosynary corporations into one single form, the “private corporation aggregate” or, as it soon became known, given that corporations sole had ceased to exist, the “private corporation.” Further, the United States created a new distinction, between “public” and “private” corporations. The action began in the courtrooms rather than the legislatures. The U.S. Supreme Court first began to articulate a public/private corporate distinction in Terret v. Taylor (1815).3 The case concerned Virginia’s post-Revolutionary dissolution of a colonial corporation sole, the office of a bishop, or “persona ecclesiae,” which had existed to convey property through a corporation aggregate ecclesiastical, the Episcopal Church. After the dissolution, Virginia expropriated the church’s property. Justice Joseph Story, writing for the majority, ruled that the state could not do so. By judicial fiat, Story distinguished “public corporations,” namely, those “which exist only for public purposes, such as counties, towns, cities, & c.” from “private corporations.” Justice Story declared that in 1776 the Episcopal Church had unwittingly transformed from a corporation aggregate ecclesiastical into a “private corporation.” And as it was a “fundamental principle” of a republican government to protect “the right of the citizens to the free enjoyment of their property,” Virginia therefore could not take the Episcopal Church’s property.

The public/private distinction Story articulated in Terret ultimately would stick. What is potentially misleading is that Story was not saying that “private corporations” were not public too. That i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: origins

- PART II: institutional forms

- PART III: moral grounds and limits

- Notes

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index