eBook - ePub

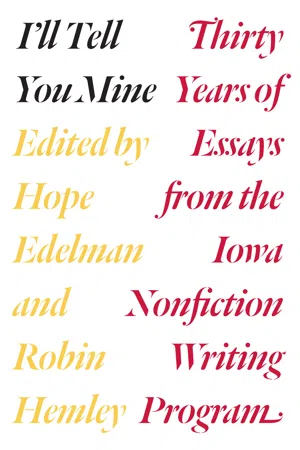

I'll Tell You Mine

Thirty Years of Essays from the Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

I'll Tell You Mine

Thirty Years of Essays from the Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program

About this book

The University of Iowa is a leading light in the writing world. In addition to the Iowa Writers' Workshop for poets and fiction writers, it houses the prestigious Nonfiction Writing Program (NWP), which was the first full-time masters-granting program in this genre in the United States. Over the past three decades the NWP has produced some of the most influential nonfiction writers in the country.

I'll Tell You Mine is an extraordinary anthology, a book rooted in Iowa's successful program that goes beyond mere celebration to present some of the best nonfiction writing of the past thirty years. Eighteen pieces produced by Iowa graduates exemplify the development of both the program and the field of nonfiction writing. Each is accompanied by commentary from the author on a challenging issue presented by the story and the writing process, including drafting, workshopping, revising, and listening to (or sometimes ignoring) advice. The essays are put into broader context by a prologue from Robert Atwan, founding editor of the Best American Essays series, who details the rise of nonfiction as a literary genre since the New Journalism of the 1960s.

Creative nonfiction is the fastest-growing writing concentration in the country, with more than one hundred and fifty programs in the United States. I'll Tell You Mine shows why Iowa's leads the way. Its insider's view of the Iowa program experience and its wealth of groundbreaking nonfiction writing will entertain readers and inspire writers of all kinds.

I'll Tell You Mine is an extraordinary anthology, a book rooted in Iowa's successful program that goes beyond mere celebration to present some of the best nonfiction writing of the past thirty years. Eighteen pieces produced by Iowa graduates exemplify the development of both the program and the field of nonfiction writing. Each is accompanied by commentary from the author on a challenging issue presented by the story and the writing process, including drafting, workshopping, revising, and listening to (or sometimes ignoring) advice. The essays are put into broader context by a prologue from Robert Atwan, founding editor of the Best American Essays series, who details the rise of nonfiction as a literary genre since the New Journalism of the 1960s.

Creative nonfiction is the fastest-growing writing concentration in the country, with more than one hundred and fifty programs in the United States. I'll Tell You Mine shows why Iowa's leads the way. Its insider's view of the Iowa program experience and its wealth of groundbreaking nonfiction writing will entertain readers and inspire writers of all kinds.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I'll Tell You Mine by Hope Edelman, Robin Hemley, Hope Edelman,Robin Hemley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9780226306476, 9780226306339eBook ISBN

9780226306506The Bamenda Syndrome

David Torrey Peters (2009)

(Originally published in The Best Travel Writing 2009; Winner, Solas Grand Prize for Travel Writing)

In mid-June of 2003, Raymond Mbe awoke on the floor of his dirt hut. A white moth had landed on his upper lip. In a half-sleep, he crushed it and the wings left traces of powder across his lips and under his nose. The powder smelled of burnt rubber and when he licked his lips, he tasted copper. Outside the hut, his eyes constricted in the sunlight. A steady dull thud, like a faraway drum, filtered through the trees. “I hate that noise,” Raymond told me later. “The sound of pounding herbs with a big pestle. Every time I hear it, I know that a short time later they will stuff those herbs up my nose.”

Two hours later, Raymond’s nose burned as the green dust coated the inside of his nostrils. A muscular man in a white t-shirt cut off at the sleeves held Raymond’s arms twisted behind his back. Across a table from Raymond, a loose-jowled old man in a worn-out fedora had measured out three piles of crushed herbs.

“Inhale the rest of it,” said the old man.

“Please,” Raymond pleaded, “I have cooperated today. You don’t have to force me.”

Deftly, the man in the sleeveless tee twisted Raymond’s elbows upward, leveraging Raymond’s face level with the table-top. Raymond considered blowing away the herbs. He found satisfaction in defying them, but already his arms burned with pain. He snorted up the remaining piles of green dust. From his nostrils ran herbs coated in loose snot. The piles gone, Raymond’s arms were given a final yank and released.

“Oaf,” Raymond muttered and wiped his face with his shirt. No one paid attention; already the old man had motioned to an androgynous creature in rags to approach him. Four other patients stood in line waiting for their turn.

In the bush that ringed the compound Raymond pretended to relieve himself. Glancing around him to make sure no one watched, he fell into a crouch and crept into the foliage. The scabs on his ankles split anew at the sudden effort. Pus seeped down onto his bare feet and he briefly remembered that he had once had a pair of basketball shoes. They had been white, with blue laces.

One hundred yards or so into the bush, he emerged onto a small path that ran in a tunnel through the foliage. Raymond stood up and began walking, brushing aside the large over-hanging leaves as he went. In places, the sun shone through the leaves, shaping a delicate lacework on the path. The tunnel dilated out onto the bright road. It had been three months since Raymond had seen the road. Under the mid-morning sun, heat shimmered off the pavement and mirages pooled in the distance. The road appeared empty.

“So, I did it. I placed a foot on the road. Very close to where I had last seen my mother. Then I walked across.”

“Oh it was terrible,” said the tailor who works alongside the road, “We heard him screaming and laughing down on the road. He was like an animal or something possessed. I was scared.”

In June, I traveled to a village named Bawum, outside the city of Bamenda in the Anglophone Northwest Province of Cameroon, to interview a priest named Father Berndind. Bawum consisted of a single road, high in the cool grasslands, lined for a mile or so with cinderblock dwellings and the occasional open-front store. Behind the houses ran a network of dirt footpaths connecting poorer thatch-work houses built of sun-dried brick or poto-poto.

Berndind had launched a campaign to eradicate the practice of witchcraft from his parish. Plenty of priests wanted to do away with witchcraft; Berndind was unique because he waged his campaign from a seminary that bordered the compound of a witchdoctor. His neighbor was Pa Ayamah, a healer renowned for his ability to cure cases of insanity caused by witchcraft.

I went to Bawum with a post-graduate student named Emmanuel, a thoughtful, good-natured guy who grew up in one of the sun-dried brick houses across the road from both Ayamah and the seminary. We agreed that he would introduce me to both Berndind and Ayamah as a friend rather than a foreign research student if I paid for food and transportation. He had written a Master’s thesis on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. “It’s funny,” he said, “You come from America to study Cameroonians, and all I want to do is study Americans.”

We arrived on a Saturday night. Emmanuel took me to Mass the following morning to meet Berndind. The church was bright and airy, but struck me as weirdly out of place among the green underbrush and dirt paths. It was built in a pre-fab style; the type of church that I remember having seen in lower-middle class areas of Iowa and Nebraska. On closer inspection, I saw that parts of the church had been hand-built to look prefabricated. Inside, I felt underdressed. I was the only man not wearing a sportcoat. In Yaoundé, fashion tended towards the sort of suits worn by comic-book super-villains; lots of bright color, wide pinstripes, and shimmery ties. From the somber colors assembled in that church, I gathered that the trend did not extend out into the provinces.

I felt better when a young man who wore a ratty blue t-shirt and taped-together flip-flops wandered in. He was short and strangely proportioned, a squat upper body rested on thin legs, like a widow’s walk on Greek-revival columns. He plunked himself down in the pew in front of me. Seated, his feet barely brushed the ground. Halfway through the Mass, he craned his head around and stared at me. He pointed at my chest and whispered loudly, “Hey! I like your tie! Very shiny!”

A wave of heads spun around to appraise my clothing choice. “Um. Thank you.” A few older men glowered at me and I blushed.

After the Mass, while I waited outside the church to meet with Berndind, I saw the boy walk by and slip into a thin trail that led into the bush. “What’s the story with that guy?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s Raymond.” Emmanuel said, “Nobody pays any attention to him. He’s a patient at Pa Ayamah’s.”

“I wasn’t there,” said Emmanuel’s sister, “But I heard about it. They had to take him back bound at the wrists and ankles.”

“Your teeth have worms in them,” George Fanka told Emmanuel. We had stopped to visit Emmanuel’s Aunt Eliza, before going to Bawum. “That’s why they hurt. They are filled to bursting with worms.”

“Worms?” Emmanuel asked.

“I am good with worms,” George Fanka assured him. “I can pull worms out of pile also.”

George Fanka did not fit my idea of a native doctor. He was my age and sported a Nike track suit. He styled his hair like a mid-Nineties American rapper and a cell phone hung from a cord around his neck. A few years prior, Emmanuel’s Aunt Eliza had come down with a mysterious illness. She spent a good chunk of her life savings on doctors unable to give her a diagnosis before she hired George Fanka to come live with her and treat her. She was a bulky, ashen-faced woman whose frequent smiles were followed by equally frequent winces. Once too ill to stand, under Fanka’s care, she had recovered enough to walk into the town center.

The night I met George and Aunt Eliza, we sat in her cinderblock living room drinking orange soda. For more than two hours George talked about his abilities as a healer. “Well, Sir,” he said when conversation turned to successful treatments, “I come from a long line of doctors. It’s in my blood. My uncle is a famous doctor.”

“That’s why he came here,” Emmanuel said, nodding at his aunt. “She needed someone who could live here and George’s uncle recommended him.”

“Everyone in my family has the ability. There are contests you know. Yes, contests. Contests.” George repeated certain words, as though his audience were intermittently hard of hearing. “All the doctors get together and we compete to see who is the best. I won a contest, you know.” He talked quickly and eagerly.

He took a swig of orange soda, smacked his lips, and hurried on. “I won a contest and that’s how I lost my toes. Well, only on one foot but that’s how I lost them. I’m a diviner; that’s what I do best.”

“Wait, you lost your toes?”

“On my right foot.” Abruptly, he dropped his soda bottle on the table. Emmanuel lunged forward to keep it from spilling. George didn’t notice; he was already bent over in his chair, tugging off his Nikes. He gripped his sock by the toe and pulled it off with a flourish, like a waiter revealing a prized entrée.

He was right. His right foot had no toes. There was a line of angry, puckered scars where his toes had been. They looked disturbingly like anuses. Aunt Eliza said something in a flustered Pidgin to George, who was proudly inching his foot towards my face. Emmanuel moved as though he were going to intercept George’s foot, but when he saw me lean in for a better look, he leaned back and asked, “Are you scared?”

“No,” I said, “Just caught me by surprise.”

“Yes, sir!” said George, ignoring the interruption, “My toes were burned off by lightning. After I won the contest, I was too proud—I had been playing with my abilities too much. So someone threw lightning to hit me, but it just got my foot.”

George was still holding his foot high in the air, speaking from between his legs. I peered closely at his foot. “Take a good look!” George said gleefully.

A number of people in Cameroon claimed the ability to throw lightning. I had asked about the phenomenon repeatedly, but while everyone said it was possible—and some had even promised to introduce me to people who could do it—tracking down lightning-throwers seemed to be a wild goose chase. An English anthropologist named Nigel Barley had spent a year with the Dowayo tribe in Northern Cameroon asking about lightning rituals, only to find that their method of directing lightning was to place marbles imported from Taiwan in little bowls set on the mountainside. My own investigations into the phenomenon were inconclusive. My best lead, a professor at the University of Yaoundé, had suggested that lightning could be thrown by coaxing a chameleon to walk up a stick.

Nonetheless, there have been some very strange lightning strikes across Africa, many of them having to do with soccer. On October 25, 1998, 11 professional soccer players were struck by lightning in a crucial game in South Africa. Two days later, 11 Congolese soccer players were killed by a second lightning strike, this time a ground steamer. The worst lightning strike ever recorded occurred at a third soccer game in Malawi, when lightning struck a metal fence, killing five people and injuring a hundred more. The official response of African soccer officials to the lightning strikes speaks to the common interpretation of these events: they banned witchdoctors from the African Nations Cup.

I had no idea what toes burnt off by lightning might look like, but if I had to imagine, they would have looked something like the scarred puckers lined up on George’s foot. I wondered if he had maybe cut his toes off himself, or lost them in an accident, but the wounds looked cauterized, like they had drawn up into themselves.

“Yes, sir,” George continued from between his legs. “It might have been another jealous healer, or maybe the spirits thought I was too bold.”

I asked George if he could throw lightning. He dropped his leg and cried, “Certainly not! I am a healer and a Christian.” He fixed me with an offended expression and wagged his finger back and forth. “That sort of thing is not what I do. What I do is, see, hold on . . .” He grabbed an empty glass from in front of him. “I make soapy water and I tell it what a person’s illness is. Then I look into the water and I can see which kind of herbs I need to find. The next day I go out into the forest and get them.”

“I get headaches,” I said. “Do you have something for that?”

“And my teeth hurt,” Emmanuel said. George looked up my nose and at Emmanuel’s teeth. I needed to sneeze more, he told me. Emmanuel, he diagnosed, had teeth full of worms. We made an appointment to return the next day for treatment.

Pa Ayamah’s compound looked similar to all the other compounds that dotted the green hills of Bawum: a few huts of sun-dried brick in a clearing surrounded by dense bush. In places, the sun sparkled through the tall trees and sent shadows flitting across soil padded smooth by human feet. Even in rural Cameroon, I had expected an insane asylum to look somewhat clinical—whether or not it was run by a witchdoctor. I saw none of the usual tip-offs: no nurses, no white buildings, no corridors or wards. Only the weathered, hand-painted sign, “Pa Ayamah—Native Doctor,” marked that I had found the right place.

In front of a smattering of brown huts, dusty men in chains shuffled about an open yard. Others not chained had their feet encased into makeshift stocks of rough wood. Everyone smiled at me, as if I were a regular stopping in for an evening beer at the neighborhood bar. A man with his hands tied to his belt tried to wave in greeting and nearly pulled himself over. He grinned ingratiatingly, obviously wanting me to share the joke. I managed a disoriented smile and realized that I had never before seen anybody tied up. A very old man with sunken eyes approached me and held out his hand. Without thinking, I reached to shake it, but recoiled when I saw that it was purple with infection.

“Antibiotics?” the man said hopefully.

Behind me, Raymond burst out from one of the huts, barefoot, pulling on a t-shirt as he ran. “Hey! I saw you at church!” he cried.

I turned with relief away from the old man. “Oh yeah,” I said, my voice more eager than I intended, “I remember!”

“You do?” Raymond came to a stop in front of me.

“Yes. I do.”

“And I remember you!”

We beamed at each other.

“What’s your name?” Raymond asked.

“Dave.”

“Antibiotics?” the old man said again, thrusting his purple hand towards me.

“No, no!” Raymond said loudly, leaning in towards the old man. “He’s a missionary.”

“What? No, I’m not.”

“But you’re white. And I saw you at church.”

“I’m a student. I came to talk to Pa Ayamah”

“Never seen a student here,” Raymond commented. “But, oh, come, I’ll show you where Ayamah stays.” He grabbed me by the arm and pulled me away from the old man, whose parched voice faded as I walked off. “Antibiotics?”

Raymond led me on an impromptu tour of the compound, tugging me along by my sleeve. A good portion of Ayamah’s land was devoted to raising corn, planted in rows of raised dirt. Beyond the cornfields were small houses, where women related to the patients lived and prepared food. Raymond confessed that he had no relations among the women, but many of the patient’s families couldn’t afford both the treatment and food, so a female relative was sent to care for the patient. The few women I saw did not give me the same welcoming smiles as their relatives. I tried to say hello to a pretty girl beating laundry in a soapy bucket. She returned my greeting with a sneer, as if she had caught me attempting to watch her bathe.

Beyond the women’s huts were the patients’ quarters. The huts were small and dirty, each with a fire pit in front. An aging man with a barrel chest and wooly hair chased chickens with a broom. He was laughing and shrieking. When he cornered a chicken, he spit on it and clapped his hands delightedly. “That’s where Pa Ayamah is,” Raymond said. I followed his finger to a long building with a tin r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue: How Nonfiction Finally Achieved Literary Status

- One Blue Note

- Black Men

- Borders

- Cousins

- O Wilderness

- Anechoic

- Round Trip

- Bruce Springsteen and the Story of Us

- The Rain Makes the Roof Sing

- How I Know Orion

- Grammar Lessons: The Subjunctive Mood

- JUDY! JUDY! JUDY!

- The Bamenda Syndrome

- High Maintenance

- Slaughter

- Things I Will Want to Tell You on Our First Date but Won’t

- The Last Days of the Baldock

- Desperate for the Story

- Acknowledgments

- Editors and Contributors