- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sociological research is hard enough already—you don't need to make it even harder by smashing about like a bull in a china shop, not knowing what you're doing or where you're heading. Or so says John Levi Martin in this witty, insightful, and desperately needed primer on how to practice rigorous social science. Thinking Through Methods focuses on the practical decisions that you will need to make as a researcher—where the data you are working with comes from and how that data relates to all the possible data you could have gathered.

This is a user's guide to sociological research, designed to be used at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Rather than offer mechanical rules and applications, Martin chooses instead to team up with the reader to think through and with methods. He acknowledges that we are human beings—and thus prone to the same cognitive limitations and distortions found in subjects—and proposes ways to compensate for these limitations. Martin also forcefully argues for principled symmetry, contending that bad ethics makes for bad research, and vice versa. Thinking Through Methods is a landmark work—one that students will turn to again and again throughout the course of their sociological research.

This is a user's guide to sociological research, designed to be used at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Rather than offer mechanical rules and applications, Martin chooses instead to team up with the reader to think through and with methods. He acknowledges that we are human beings—and thus prone to the same cognitive limitations and distortions found in subjects—and proposes ways to compensate for these limitations. Martin also forcefully argues for principled symmetry, contending that bad ethics makes for bad research, and vice versa. Thinking Through Methods is a landmark work—one that students will turn to again and again throughout the course of their sociological research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2017Print ISBN

9780226431727, 9780226431697eBook ISBN

9780226431864* 1 *

Sharpen Your Tools

Methods are means to an end, and you control them by using things in your brain, like concepts, which are mental tools. You don’t want hand-me-down tools that are rusty with neglect. Know what you are doing and be willing to defend it.

What Are Methods of Sociological Research?

What Is Research?

This is a book about how to do sociological research. And so I think it is appropriate to talk about what research is. It is, first and foremost, work. One does not do work for nothing. Why do it? Even if you think it is only done for self-centered reasons (e.g., to get an A in a class, to get an article published, to get a job, or to get tenure), that begs the question of why there is a system in which this work is required.

The answer is that social science is one of the types of knowledge that require work to be done right, often very hard work, over long stretches of time, often on the part of many different people. Methods are about the how of this work. That means that if you’re not interested in methods, it’s like being a violinist and not being interested in playing. This is what you do all day . . . if you’re really doing something. And to get these methods to do something for us, we need to use them seriously, not ritualistically, and think them through.

How Do We Use Our Brains?

One of the things about our partition of sociology into theory, methods, and substance is that we forget that we can use our brains not just in the theory part but also in the methods part. In fact, the key argument of this book is that we need to “theorize” our own practice . . . not in the sense that most folks mean by “theorize,” which is basically to toss a lot of fancy abstractions around hither and thither. I mean the opposite—we need to really have a scientifically defensible understanding of what we are doing before we give much credence to the results. If you were a contaminant ecologist attempting to see whether fish in some lake had too many toxins, you wouldn’t just stop by a fish fry some folks are having and take a nibble, would you? So why do the equivalent as a sociologist?

In order to understand what our data—our experiences and interactions with the world—mean for us, we need to spend a fair amount of time understanding “where” in the world we are, and what we are really doing. We’re going to be trying to think about both the planned and the unplanned aspects of research. Let’s start with the planned parts. The most straightforward way that we use our brains in research is to construct a research design—a plan for future research that guides our data collection efforts so that we can compile our data usefully, and that guides our data compilation efforts so that we can bring our data to bear on the questions we’re interested in. The key to research design is understanding which kinds of problems are most likely to be relevant to our proposed case of research and seeing if we can be clever enough to avoid a head-on collision with them.

A good research design can avoid many problems, but not all. Much of the difficult work comes in ways that our research design didn’t anticipate or wasn’t relevant for. For this reason, we will find that we need to think through—carefully, rigorously, and without mystification or wishful thinking—all the steps that go into making our claims (also see Latour 2005, 133), starting from the very first: “How did I get interested in this question? Where did I get the concepts I use to think about it?” And then on to: “How did I end up at this particular site? Why am I talking to these people and not those?” Or, “Why am I looking at these documents and not those?” And then on to things like: “When someone says, ‘Yes, I approve of Obama’s foreign policy’ to me, what is going on? What did I say to provoke this? What was the setting in which this was embedded?” and so on. If you do this, you have a remarkably good chance of doing something worthy of being called social science.

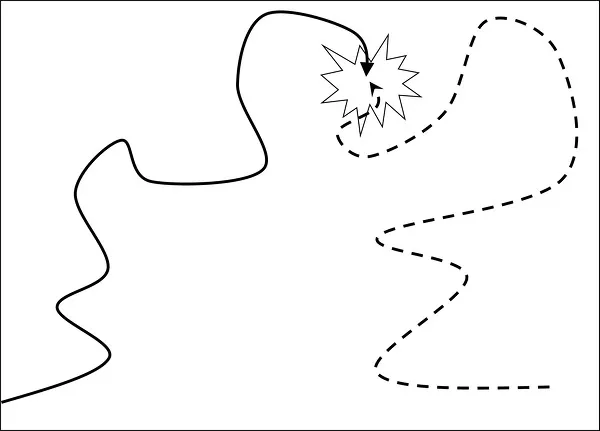

In other words, the process of producing knowledge can be understood impressionistically as a meeting between your mind and some part of the world (perhaps a particular person at a particular place saying a particular thing). To understand what this interaction produces, to make it truly a datum, as opposed to a profound mystery, requires reconstructing, as best as we can, the nature of the meeting. Figure 1 gives a schematic rendition of this process. The rectangle you are in represents all the “places” (analogically speaking) you could have this interaction. The solid line represents your path, and the broken line that of the part of the world.

What is your path? Perhaps something very simple: you wanted to study young Americans’ attitudes toward sexual preference—do they see it as genetic or not? Already, in a way, you have started moving down one path, merely by thinking of this question and not others, and in formulating the terms in which you are thinking about it (perhaps you are assuming that “biological” and “genetic” mean the same thing to people). But then you make other choices. First, you stayed in the city where your own school is, as opposed to going to one of the other twenty-five thousand towns and cities in the United States. Second, you got permission to pass out flyers in the lunchroom at two high schools, as opposed to the other two hundred schools in the area. And then you waited.

Some parts of the process happened behind the scenes, as far as you were concerned. Students got the flyers. Some immediately became paper airplanes. Others were the subject of guffaws in the cafeteria. Some were carefully folded and put in a back pocket, sometimes by a guffawer. Others were stuffed into textbooks. Some of those folded and stuffed flyers were only found months later. Some were found soon, and here and there, a student pondered whether to volunteer. More decided to volunteer than actually called you. Some called, but when you weren’t there, they didn’t leave a message; perhaps especially those without their own phones. Some made plans to meet with you but never showed. And when they did, you asked some particular questions (among others)—a few out of the near infinite number you could have asked. And only then did you get your (potential) information in response. This answer is only a datum when it can be placed, with great imprecision, of course, in this overall landscape of acts of choice and selection.

I will be emphasizing this selection and selectivity throughout. We often now may associate this issue with causal estimation. That’s only one teeny part of selectivity. It’s about the choices that we make, and those that others make. We can’t control others’ choices, but we can theorize them. And we can control our own. So make good choices. To do this, we need to pursue our investigations with symmetry, with impartiality (sine ira et studio, as Weber would say), and without bad behavior on our side. I’m going to be arguing that you need to really pursue this ideal, and not simply in some vague lip-service, recognize-it’s-best-but-not-plausible-for-mere-mortals way, but as in, when someone draws your attention to a lapse here, you fix it. Sure, smart aleck reader, I also read the philosophy of science, and I admit that I can’t prove to students that this is necessary, if you are going to do valid social research. But students have proven it to me.

To orient ourselves, let’s back up, and see what we’re doing with this whole “methods” thing.

Methods in General

There are some things that are—or should be—common to all sociological methods. First, sociological methods are, I believe, driven by a question. That might sound funny or obvious, but it’s not; in fact, most sociologists seem to disagree with me here. But I think that things we do that aren’t driven by a question aren’t methods—they’re not a means to an intellectual end. They’re dressing, ritual, whatever.

Second, sociological methods involve a good faith attempt to find a fair sample of the universe at question. Not a “representative” one, but a fair one. A question has multiple places where it can be answered, and your answer may depend on which place you examine. For example, say you start with the question, “Does strong leadership increase or decrease members’ attachment to the group?” You might get a different question if you looked at army platoons than if you looked at the history of the British monarchy.

There are two implications. The first is that if you have an answer you want to find, it isn’t fair to choose a site that’s likely to give you the answer you want. The second implication (which I’ll discuss more in the next chapter) is that if it really seems like your answer completely depends on where you look, you don’t yet have a proper question.

Third, sociological methods push us to be systematic in answering the question, allowing for disconfirmation of our hunches as opposed to selectively marshaling the evidence we want. In the most satisfying cases, we construct a “research design” like the mousetrap in that board game—a whole elaborate machinery is set up, then we pull the switch (by collecting our data), and see what happens.

It’s rare for research to unfold so mechanically. And for that reason, sometimes we need to be “unsystematically systematic.” That is, we have to figure out what’s the sort of evidence that we haven’t seen yet and that might lead to a different conclusion. (This is what Mitchell Duneier [2011] calls “inconvenience sampling.”)

Fourth, sociological methods tend—if only for rhetorical reasons—to stress comparison and hence variation. It’s hard to know if you’re right or wrong in explaining something that doesn’t vary—something that’s always there. So some of the most interesting questions get ignored. Questions like “Why do people use language?” or “What causes patriarchy?” aren’t ones we can do much with. Something that does vary, however, is amenable to explanation via comparison. I’m not actually so sure a focus on comparison is always a good idea, but it is a central aspect of sociological methods, so we would do well to understand it.

Those four traits are basic to most methods. Past these commonalities, we will find that different methods have different advantages depending on, most important, what the process is (or was) that is of interest to us. Is it social-psychological? Institutional? A historical development? Second, which method is most appropriate will turn on whether the effects of this process are . . . repeatable or not? Generalizable to all people or only to a group? Conscious or not conscious (can you get the information by asking or must you watch)?

Depending on what we think we’re studying, we’re going to take a different approach. And—silly though it sounds, I know—to know what we think we’re studying, we’re going to need to make a few provisional decisions about what we think is out there in the world.

Things and Concepts

What Is Real? What Can Act? What Is a Concept?

Theory is a funny thing. Among the tricks it can play on us is leading us to devote long periods of our lives to the examination of things that, in our saner moments, we would concede do not exist.

Do you want to argue about what “real” means and start a rumble over realism? I don’t. All we need to do is to use the word “real” to denote the stuff we’re absolutely committed to defending. That means something that probably has most of the following properties. First, we think it’ll still be there if we come back tomorrow (it’s “obdurate”—though we don’t deny that some phenomena are transitory). Second, we think that other people will be able to see it too (it’s “intersubjectively valid”—though we don’t deny that sometimes you have to learn to notice certain phenomena). Third, you can study it via a number of different methods (it’s “robust under triangulation”—though we recognize that sometimes we don’t yet have ways of getting information on people’s thoughts other than talking to them, and so on). Something that lacks one of these properties might still deserve our commitment. But something that lacks all of them—it comes and goes, not everybody can see it, and only some methods reveal it—that doesn’t seem like the kind of thing we call “real,” does it? It sounds more like a ghost.

Sometimes we end up chasing ghosts because we are enamored of a theory that makes strong claims about the world. The simplest way in which this messes with our heads comes from what is called “reification” or “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” In our case, that means that we take a “theoretical” phrase or a concept—something that should really be a shorthand that helps us organize our thoughts about the world—and treat it as if it were a thing. Once it becomes a thing, it is easy for us to imagine that it can “do things” that we include in our explanation. For example, many sociologists are interested in capitalism as a mode of production rooted in the private appropriation of productive capital. Even if we assume that there is a utility to this theoretical construct (which I’ll continue to use as an example below), it doesn’t mean that capitalism is really a thing that exists somewhere.

There are times when it is going to help to decide, before you begin, what you think is real enough to make things happen. The reason is simple—that’s the stuff you need to get data on. Once we’ve done that, we can begin to think methodologically. I’m going to start laying out the conventional understanding of sociological methods. I don’t think that this understanding is defensible in all aspects, but it is important that you understand it, and appreciate its strengths and limitations, before we go much further.

What Is a Unit of Analysis?

Let me start by quickly going through some pretty conventional language that we’ll need. Most folks will tell you that any sociological investigation involves a choice of the unit of analysis (UOA). These days, we frequently do comparisons across more than one case (or instantiation) of the unit of analysis.1 We generally have a question about some sort of variation or differences among instantiations of our UOA. Here are examples: does labor unrest affect a nation’s employment insurance policies? Do cities with higher levels of income inequality have higher rates of crime? Are religiously orthodox individuals more or less hostile to immigration?

Very frequently UOAs are nested, in that there are distinct levels of analysis. For example, nations are composed of states or provinces, which are composed of counties, which include towns. And sometimes it helps to see all of these as composed of individuals. Because of this, we frequently refer to the question of the choice of UOA as a choice of the “level” of analysis.

Obviously, the choice of UOA determines the research design. If you’re going to compare UOAs, for example, you will miss everything if your choice is wrong. For example, imagine that income inequality does lead to increased crime at the level of the nation but not at the level of the city—say, because the processes have to do with cultural senses of fairness and opportunity and not material opportunism. You could come up with a null finding if you compare cities within the United States. Obvious, true, but still the sort of obvious thing that we overlook as we rush to “get started.”

Finally, there may be theories or questions that we believe to hold at more than one UOA. For example, we may say that increasing income inequality leads to increased crime at any level of analysis: town, county, state, or nation, say. While there might be times when this makes sense, it’s usually a worrisome signal that we’re tossing words around somewhat randomly. Since it’s unlikely that the processes involved at these different levels could be the s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Sharpen Your Tools

- Chapter 2: How to Formulate a Question

- Chapter 3: How Do You Choose a Site?

- Chapter 4: Talking to People

- Chapter 5: Hanging Out

- Chapter 6: Ethics in Research

- Chapter 7: Comparing

- Chapter 8: Dealing with Documents

- Chapter 9: Interpreting It and Writing It Up

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

- Footnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Thinking Through Methods by John Levi Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.