- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

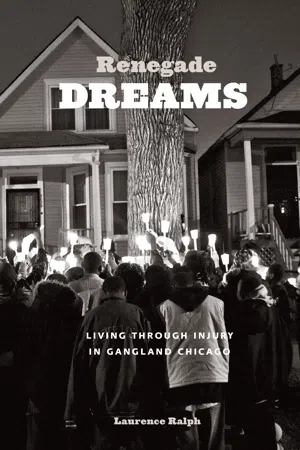

Every morning Chicagoans wake up to the same stark headlines that read like some macabre score: "13 shot, 4 dead overnight across the city," and nearly every morning the same elision occurs: what of the nine other victims? As with war, much of our focus on inner-city violence is on the death toll, but the reality is that far more victims live to see another day and must cope with their injuries—both physical and psychological—for the rest of their lives. Renegade Dreams is their story. Walking the streets of one of Chicago's most violent neighborhoods—where the local gang has been active for more than fifty years—Laurence Ralph talks with people whose lives are irrecoverably damaged, seeking to understand how they cope and how they can be better helped.

Going deep into a West Side neighborhood most Chicagoans only know from news reports—a place where children have been shot just for crossing the wrong street—Ralph unearths the fragile humanity that fights to stay alive there, to thrive, against all odds. He talks to mothers, grandmothers, and pastors, to activists and gang leaders, to the maimed and the hopeful, to aspiring rappers, athletes, or those who simply want safe passage to school or a steady job. Gangland Chicago, he shows, is as complicated as ever. It's not just a warzone but a community, a place where people's dreams are projected against the backdrop of unemployment, dilapidated housing, incarceration, addiction, and disease, the many hallmarks of urban poverty that harden like so many scars in their lives. Recounting their stories, he wrestles with what it means to be an outsider in a place like this, whether or not his attempt to understand, to help, might not in fact inflict its own damage. Ultimately he shows that the many injuries these people carry—like dreams—are a crucial form of resilience, and that we should all think about the ghetto differently, not as an abandoned island of unmitigated violence and its helpless victims but as a neighborhood, full of homes, as a part of the larger society in which we all live, together, among one another.

Going deep into a West Side neighborhood most Chicagoans only know from news reports—a place where children have been shot just for crossing the wrong street—Ralph unearths the fragile humanity that fights to stay alive there, to thrive, against all odds. He talks to mothers, grandmothers, and pastors, to activists and gang leaders, to the maimed and the hopeful, to aspiring rappers, athletes, or those who simply want safe passage to school or a steady job. Gangland Chicago, he shows, is as complicated as ever. It's not just a warzone but a community, a place where people's dreams are projected against the backdrop of unemployment, dilapidated housing, incarceration, addiction, and disease, the many hallmarks of urban poverty that harden like so many scars in their lives. Recounting their stories, he wrestles with what it means to be an outsider in a place like this, whether or not his attempt to understand, to help, might not in fact inflict its own damage. Ultimately he shows that the many injuries these people carry—like dreams—are a crucial form of resilience, and that we should all think about the ghetto differently, not as an abandoned island of unmitigated violence and its helpless victims but as a neighborhood, full of homes, as a part of the larger society in which we all live, together, among one another.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Renegade Dreams by Laurence Ralph in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226032719, 9780226032689eBook ISBN

9780226032856One

The Injury of Isolation

INTRODUCTION

THE UNDERSIDE OF INJURY

OR,

How to Dream Like a Renegade

Justin Cone tilted in his wheelchair. He executed this delicate balancing act effortlessly, while simultaneously craning his head to take in the audience behind him. His neck muscles began to bulge as he surveyed the teenagers. He was perched in the front row of a high school assembly on gang violence in Chicago. It was the winter of 2008; twenty-seven public school students had been killed since September. This was an unprecedented number at the time. Little did Justin and I know that the bloodshed would only increase. The ignoble number of deaths in 2008 would be surpassed year after year after year. By the end of 2011, three years later, 260 would be dead.1

Justin had been to many such assemblies, but this time he encouraged me to come with him. There was something remarkable about these particular speakers, he promised—something that a gang researcher just had to see for himself. I soon found out what Justin deemed extraordinary: the young men onstage looked like him. They, too, used to belong to a gang and had been disabled by a gunshot; now they were onstage, calling attention to their wounds.

“Watch this,” Justin said, directing my attention to the stage. (I had been looking down, fiddling with my recorder—making sure the device had enough digital space to capture what the speakers were about to discuss.)

“They’re gonna make folks really uncomfortable now,” he said.

As my eyes focused on the stage, I saw that the disabled ex–gang members were holding plastic bags and medical tubing in outstretched arms, explaining in precise and graphic detail the daily realities of life in a wheelchair. The teenagers squirmed as they realized that the men were holding catheters and enema bottles. Justin gave me an I-told-you-so look. The men onstage calmly segued from medical necessities to larger truths; their bodies now bear witness to violence—violence that can and should be prevented.

“They say when you gang bang, when you drug deal, the outcomes are either death or jail,” Tony Akpan, one of the disabled speakers announced from the stage. “You never hear about the wheelchair. I didn’t know this was an option. And if you think about it, it’s a little bit of both worlds ’cause half of my body’s dead. Literally. From the waist down, I can’t feel it. I can’t move it. I can’t do nothing with it. The rest of it’s confined to this wheelchair. This is my prison for the choices I’ve made.”

After listening to members of the Crippled Footprint Collective, I began to see the novelty of what disabled ex–gang members were doing in Chicago. I started to realize that in Chicago, the disabled gang member emerges as a prominent figure—one who highlights the sobering realities of coming of age in a poor community under a persistent cloud of violence. Anti-violence forums like the one that Justin and I attended, and others that I would help organize, revealed aspects of the gang experience scarcely mentioned in ethnographic studies of street gangs. Contemporary scholarship fails to acknowledge that victims of gun violence are much more likely to be disabled than killed.2 Chicago is a prime example of this trend: over the past fifteen years, more than 8,000 people have been killed, while an estimated 36,000 have been debilitated.3

When I sat next to Justin at that high school assembly, I wasn’t aware of these statistics; nor did I know that the former gang affiliates onstage would inspire him to pursue a new career path. Soon after the talk, Justin proclaimed that he wanted to be an anti-violence activist. “If the killings won’t stop,” he explained, “then we’re gonna need more hands on deck.”

Justin already worked at a violence prevention agency, Safe Futures; but he was now motivated to learn the craft of public speaking. He wanted to tell his story to gang-affiliated youth in Chicago and eventually start a violence prevention organization of his own. After watching the Crippled Footprint Collective, he had a new mission. “I’ve never been more sure about anything in my life,” he said a few weeks after the assembly.

That conversation came at the beginning of what would be three years of ethnographic fieldwork in Eastwood. I had come to Eastwood to study gang violence. But I soon started realizing something else: Justin’s disability was obvious because of his wheelchair. But in Eastwood, injury was everywhere. And injury took many different forms. There, people did not merely speak of injury in terms of gunshot wounds. Longtime residents saw injury in the dilapidated houses that signaled a neighborhood in disrepair; gang leaders saw injury in the “uncontrollable” young affiliates who, according to them, symbolized a gang in crisis; disillusioned drug dealers saw injury in the tired eyes of their peers who imagined a future beyond selling heroin; and health workers saw injury in diseases like HIV and the daily rigors of pain and pill management that the disease required. “These pills,” an HIV patient, Amy O’Neal, told me, “they teach me that every day’s a battle between life and death.”

As I spent more time with Eastwoodians like Amy, I witnessed how injury invaded people’s lives. People in Eastwood interpreted injury on a vast spectrum; they forced me to stop thinking of this concept as an objective condition, something that a doctor could identify or diagnose. Instead, I began to think of the myriad injuries that Eastwoodians described as encumbrances that followed them through life, weighed them down, and affected their future prospects. Even further, I saw that injury wasn’t just physical. I learned that community redevelopment projects of the local government—despite its good intentions—also injured Eastwoodians; so, too, did historical emotions like nostalgia and philosophical sentiments like authenticity. Over time, this range of injurious possibilities started to inform the way I thought about the diseases and disabilities (and other kinds of physical harm, like addiction) that disproportionately impacted poor black communities like Eastwood. And I realized the limits of how scholars and experts have been talking about violence and injury, even when they are trying to help places like Eastwood.

What really struck me was this: each time that I sat in a teenager’s house and listened to him tell me about the pressures to seek retribution after a close friend was killed or I heard former gang members recounting stories about being gunned down and left for dead, I immediately noticed the evidence of injury. Bodies that were partially immobilized, futures that seemed destined for pain and disappointment. Then I noticed the bulging necks and fierce eyes of Eastwoodians as they told me their stories. Bodies that despite their injuries weren’t slunk or broken, but upright and inspired. Minds that weren’t consigned to a life of drudgery, despite terrible odds, but were busy planning for the future. Eastwoodians weren’t afraid to dream of a better life. Whether dreaming meant pursuing a new career path, imagining a different kind of gang—or both—in Eastwood, injury was intimately tied to dreaming. But how can we understand this kind of inheritance?

There are so many kinds of dreams.4 But in the long tradition of African American activism, dreams have typically been linked to concrete aspirations for social reform. In his 1951 poem “Harlem,” Langston Hughes, writer and social activist, famously questioned the outcome of a “dream deferred.” Does such a dream dry up, fester, stink, crust and sugar over, or sag like a heavy load, he pondered. Then, foreshadowing the hundreds of race riots that would take place in the 1960s and 1970s, he ends his poem with an emphatic query: Or does it explode?

It wasn’t Hughes, of course, but Martin Luther King Jr. who delivered perhaps the most well-known reference to dreaming, on August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Prompted by the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who from the crowd exhorted King to “Tell them about the dream,” King departed from his prepared text and sermonized on his aspirations of freedom and equality, and how that dream would rise from the deleterious social conditions of slavery and segregation.5 From where King stood, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, a black president might well have embodied the integrated society King longed to see. Perhaps this is why, as I began my field research, Barack Obama (the embodiment of an integrationist’s “dream deferred”) was the latest aspirant to capture the imagination of black America.

Obama’s memoir Dreams of My Father was written just before he launched his political career and draws on his personal experiences of race relations in the United States. Determined to graduate from Harvard University (the school where his immigrant black father began his studies but couldn’t afford to finish), Obama initially pursued his father’s goal, but eventually came into his own by developing his potential to lead. Inner-city Chicago figures prominently in Obama’s story, as he moves to the South Side after finishing law school and works for a nonprofit agency as a community organizer. From the difficulties of those Chicago days, as his program battled with entrenched community leaders and local government apathy, a politician was born.6

The Eastwoodians with whom I spent my days and nights over the course of three years were intimately linked to dreamers like Obama. This was not merely because he eventually became their senator and then their president, but because he learned his first political lessons in Altgeld Gardens, an inner-city neighborhood like their own. They were also linked to dreamers like Hughes, through the tortured history that led African Americans to migrate from the South and settle in northern outposts like Harlem and Chicago; they were linked to dreamers like King through civil rights organizations, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), that met and strategized in churches and parks and run-down houses all over the West Side of Chicago. Yet their Eastwood dreams were not tied to a particular social movement like the Harlem Renaissance or the civil rights crusade. No charismatic figure vocalized their aspirations for them. Quite the opposite, in fact, particularly for the young black men at the heart of this story. Local leaders often articulated the problems of their community in terms of the “crisis of the young black male.”7

The people I lived with did not speak from a position of institutional authority; they knew that no one, except maybe green graduate students, cared much about their dreams. Nevertheless, Eastwoodians—young and old, male and female alike—dreamed in ways that expressed desires for a different world. Now lest I be accused of suggesting too rosy a picture, I should say that these dreams were not grandiose. These were not the genre of dreams that have been Disney-fied and squashed into the storybook realm. In fact, when I first moved into Eastwood, I did not recognize residents’ struggles as dreams because they were often quite banal. Safe passage to school became something to dream for, as did a stable job and affordable, livable housing. These dreams, it is critical to note, didn’t always come true: Children were gunned down on the way to school; adults searched for work to no avail; the threat of displacement haunted residents daily. In the face of these hardships, the scant resources that Eastwoodians did obtain barely scratched the surface of actual need. The brutal honesty with which they acknowledged the difficulty of real change suggested that the power of such dreams is in having them and working toward them, regardless of whether or not they come to fruition.8

Another remarkable thing was this: Eastwoodians’ dreams were tied to overcoming the very obstacles—mass incarceration, HIV, gun violence—that are often discussed by reporters, government officials, and scholars in terms of the ways they incapacitate people. Slowly, I began to realize, if injury immobilizes people, like that fatal bullet that fractures the spine, then dreams keep people moving in spite of paralysis. Everywhere I went—high schools, detention centers, churches, and barbershops—I witnessed people exerting tremendous effort in a desperate attempt to pursue their passions. The more time I spent with residents like Justin and Amy, the more I began to understand: In Eastwood, injury endows dreams with a renegade quality.9

Justin’s goal to become an anti-violence activist was a prime example of the renegade spirit that dreaming in Eastwood required. He and I bonded during the many afternoons I spent volunteering at Safe Futures. The more we talked about the gang, the more I realized that this organization couldn’t be understood outside of the community that gave birth to it. I learned that to be an anti-violence activist (or an ethnographer) in Eastwood, you had to position yourself within a community rife with social problems. This positioning entailed learning about the problems specific to Eastwood.

Redevelopment, for instance, was a hot-button issue when I was conducting research. I moved to Eastwood in 2007 as a graduate student to learn everything I could about gangs. But I soon found out that if I wanted to accomplish this goal, then I also had to learn about the ways in which Eastwoodians were grappling with the threat of gentrification. (It turned out that gang members did want to talk about territory and turf, but not in the ways I expected.)10 My first task was to figure out which organizations the local gang aligned themselves with to voice their concerns about housing, and which organizations held opposing views and an alternate vision for the community; I had to recognize how the gang could sometimes symbolize all the ills of the community, but how at other times a person’s gang affiliation became submerged within the larger issue of dislocation; and I had to distinguish between the times when everything I read about poor black communities like Eastwood enhanced my perspective, and the times when everything I read prevented me from seeing what was right before my eyes. This was no easy task, in large measure due to the avalanche of books and articles—on Chicago’s gangs, its crumbling housing market, its impoverished and underperforming schools—that is published every year.11

In part because of the attention of scholars and journalists, Eastwood and communities like it attract a lot of “help.” Although the neighborhood is only about two miles wide and a mile and a half in length, Eastwood has nearly 180 nonprofit organizations. There are even more churches—187—on record, many of which are committed to social reform. And these figures don’t include the efforts of informal groups, schools, ministries, and block clubs. Additionally, in recent years select institutions that host a number of social welfare programs have teamed up with the city government to redevelop the community. In other words, Eastwood is awash with help, and yet it is not clear if all these efforts are really helping.

In 2007, not long after I began volunteering at Safe Futures, I met Aaron Smalls. He worked for the city’s Department of Planning, and he was visiting local nonprofits as part of what he called a “scouting trip.” Shortly after his visit, I scheduled a meeting with the commissioner at his office in City Hall, where he explained the local government’s interest in redeveloping Eastwood. The first thing he mentioned was that this area was “doomed for failure” because residents lacked the basic skills and qualifications to secure livable wages. Though I didn’t agree with his interpretation of “doom,” it was certainly true that of the 41,768 residents living in Eastwood, nearly half (42 percent) were below the poverty line.

“Those who are employed,” Mr. Smalls said, “often find themselves in repetitive, low-wage jobs—or without jobs altogether.” I paused for a moment to scribble down his observation. This was also true; at nearly 51 percent, Eastwood’s unemployment rate was three times as much as the rest of Chicago, and five times higher than the national average.12

“Additionally,” Mr. Smalls said, waiting for me to look up from my legal pad, “with the large population of ex-offenders—who often struggle with drug addiction, poverty, low rates of education, unemployment, and unstable housing—Eastwoodians simply don’t have the necessary resources to improve their community.” In my notebook I drew a sharp black line beneath this statement. Here, it seemed, was where Mr. Smalls’s perspective on the community diverged from the beliefs of the community itself.

The facts about Eastwood were not under dispute: 34 percent of residents between eighteen and twenty-four years of age la...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Dramatis Personae

- Preface

- Part One † The Injury of Isolation

- Part Two † The Resilience of Dreams

- Conclusion ‡ The Frame or, How to Get Out of an Isolated Space

- Postscript ‡ A Renegade Dream Come True

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index