- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Time Maps extends beyond all of the old clichés about linear, circular, and spiral patterns of historical process and provides us with models of the actual legends used to map history. It is a brilliant and elegant exercise in model building that provides new insights into some of the old questions about philosophy of history, historical narrative, and what is called straight history."-Hayden White, University of California, Santa Cruz

Who were the first people to inhabit North America? Does the West Bank belong to the Arabs or the Jews? Why are racists so obsessed with origins? Is a seventh cousin still a cousin? Why do some societies name their children after dead ancestors?

As Eviatar Zerubavel demonstrates in Time Maps, we cannot answer burning questions such as these without a deeper understanding of how we envision the past. In a pioneering attempt to map the structure of our collective memory, Zerubavel considers the cognitive patterns we use to organize the past in our minds and the mental strategies that help us string together unrelated events into coherent and meaningful narratives, as well as the social grammar of battles over conflicting interpretations of history. Drawing on fascinating examples that range from Hiroshima to the Holocaust, from Columbus to Lucy, and from ancient Egypt to the former Yugoslavia, Zerubavel shows how we construct historical origins; how we tie discontinuous events together into stories; how we link families and entire nations through genealogies; and how we separate distinct historical periods from one another through watersheds, such as the invention of fire or the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Most people think the Roman Empire ended in 476, even though it lasted another 977 years in Byzantium. Challenging such conventional wisdom, Time Maps will be must reading for anyone interested in how the history of our world takes shape.

Who were the first people to inhabit North America? Does the West Bank belong to the Arabs or the Jews? Why are racists so obsessed with origins? Is a seventh cousin still a cousin? Why do some societies name their children after dead ancestors?

As Eviatar Zerubavel demonstrates in Time Maps, we cannot answer burning questions such as these without a deeper understanding of how we envision the past. In a pioneering attempt to map the structure of our collective memory, Zerubavel considers the cognitive patterns we use to organize the past in our minds and the mental strategies that help us string together unrelated events into coherent and meaningful narratives, as well as the social grammar of battles over conflicting interpretations of history. Drawing on fascinating examples that range from Hiroshima to the Holocaust, from Columbus to Lucy, and from ancient Egypt to the former Yugoslavia, Zerubavel shows how we construct historical origins; how we tie discontinuous events together into stories; how we link families and entire nations through genealogies; and how we separate distinct historical periods from one another through watersheds, such as the invention of fire or the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Most people think the Roman Empire ended in 476, even though it lasted another 977 years in Byzantium. Challenging such conventional wisdom, Time Maps will be must reading for anyone interested in how the history of our world takes shape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Time Maps by Eviatar Zerubavel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780226981536, 9780226981529eBook ISBN

9780226924908The Social Shape of the Past | 1 |

As one can certainly tell by the fact that we do not recall every single thing that has ever happened to us, memory is clearly not just a simple mental reproduction of the past. Yet it is not an altogether random process either. Much of it, in fact, is patterned in a highly structured manner that both shapes and distorts what we actually come to mentally retain from the past. As we shall see, many of these highly schematic mnemonic patterns are unmistakably social.

Plotlines and Narratives

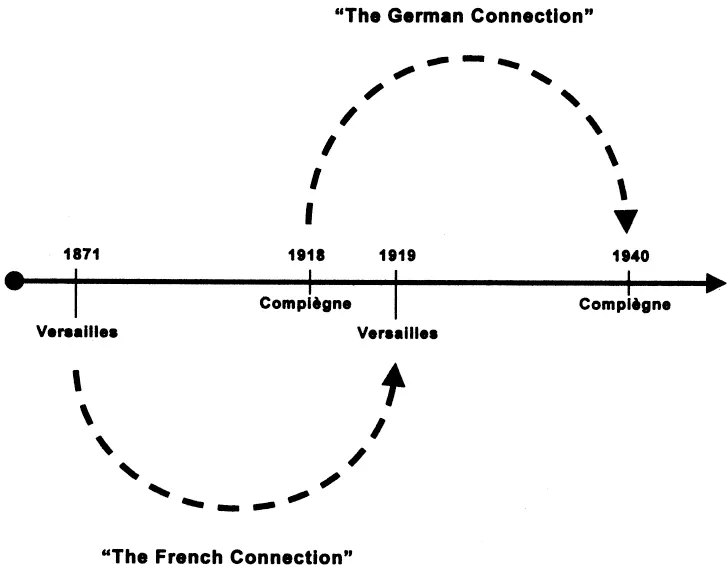

In June 1919, as a triumphant France was preparing to sign the Treaty of Versailles, it made the portentous decision to stage the final act of the historical drama commonly known as revanche (revenge) in the very same Hall of Mirrors where the mighty German Empire it had just brought to its knees was formally proclaimed almost fifty years earlier, following Prussia’s great victory in the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War. Not coincidentally, an equally pronounced sense of historical drama led a victorious German army twenty-one years later, in June 1940, to hack down the wall of the French museum housing the railway coach in which the armistice formalizing Germany’s defeat in World War I had been signed in November 1918, and tow it back to the forest clearing near the town of Compiègne where that nationally traumatic event had taken place and where Germany was now ready to stage France’s humiliating surrender in World War II:

The cycle of revenge could not be more complete. France had chosen as the setting for the final humbling of Germany in 1919 the Versailles Hall of Mirrors where, in the arrogant exaltation of 1871, King Wilhelm of Prussia had proclaimed himself Kaiser; so now Hitler’s choice for the scene of his moment of supreme triumph was to be that of France’s in 1918.1

Soon after Hitler finished reading the inscription documenting the historic humiliation of Germany by France in 1918, everyone entered the famous railcar and General Wilhelm Keitel began reading the terms of surrender after explicitly confirming the choice of that particular site as “an act of reparatory justice.”2

Only within the context of some larger historical scenario,3 of course, could either of these events be viewed in terms of “reparation.” And only within the context of such seemingly never-ending Franco-German revenge scenarios can one appreciate a 1990 joke in which the tongue-in-cheek answer to the question “Which would be the new capital of the soon-to-be-reunified Germany: Bonn or Berlin?” was actually “Paris”!

Essentially accepting the structuralist view of meaning as a product of the manner in which semiotic objects are positioned relative to one another,4 I believe that the historical meaning of events basically lies in the way they are situated in our minds vis-à-vis other events. Indeed, it is their structural position within such historical scenarios (as “watersheds,” “catalysts,” “final straws”) that leads us to remember past events as we do. That is how we come to regard the foundation of the State of Israel, for example, as a “response” to the Holocaust, and the Gulf War as a belated “reaction” to the U.S. debacle in Vietnam. It was the official portrayal of the 2001 military strikes in Afghanistan as “retaliation” for the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon that likewise led U.S. television networks to report on them under the on-screen headline “America Strikes Back,” and the collective memory of a pre-Muslim, essentially Christian early-medieval Spain that leads Spaniards to regard the late-medieval Christian victories over the Moors as a “re-conquest” (reconquista).

Consider also the case of historical irony. Only from such a historical perspective, after all, does the recent standardization of the Portuguese language in accordance with the way it is currently spoken by 175 million Brazilians rather than only 10 million Portuguese come to be seen as ironic. A somewhat similar sense of historical irony underlies the decision made by the New York Times the day after the 2001 U.S. presidential inauguration to print side by side two strikingly similar yet contrasting photographs featuring the outgoing president Bill Clinton outside the White House: one with his immediate predecessor, George Bush, back in January 1993, and the other with his immediate successor, George W. Bush, exactly eight years later.5

One of the most remarkable features of human memory is our ability to mentally transform essentially unstructured series of events into seemingly coherent historical narratives. We normally view past events as episodes in a story (as is evident from the fact that the French and Spanish languages have a single word for both story and history, the apparent difference between the two is highly overstated), and it is basically such “stories” that make these events historically meaningful. Thus, when writing our résumés, for example, we often try to present our earlier experiences and accomplishments as somehow prefiguring what we are currently doing.6 Similar tactics help attorneys to strategically manipulate the biographies of the people they prosecute or defend.

As is quite evident from figure 1, in order for historical events to form storylike narratives, we need to be able to envision some connection between them. Establishing such unmistakably contrived connectedness is the very essence of the inevitably retrospective mental process of emplotment.7 Indeed, it is through such emplotment (as well as reemplotment,8 as is quite spectacularly apparent in psychotherapy)9 that we usually manage to provide both past and present events with historical meaning.

Approaching the phenomenon of memory from a strictly formal narratological perspective, we can actually examine the structure of our collective narration of the past just as we examine the structure of any fictional story.10 And indeed, adopting such a pronouncedly morphological stance helps reveal the highly schematic formats along which historical narratives usually proceed. And although actual reality may never “unfold” in such a neat formulaic manner, those scriptlike plotlines are nevertheless the form in which we often remember it, as we habitually reduce highly complex event sequences to inevitably simplistic, one-dimensional visions of the past.

Following in the highly inspiring footsteps of Hayden White,11 I examine here some of the major plotlines that help us “string” past events in our minds,12 thereby providing them with historical meaning. Rejecting, however, the notion that these plotlines are objective representations of actual event sequences, as well as the assumption that such visions of the past are somehow universal, I believe that we are actually dealing here with essentially conventional sociomnemonic structures. As is quite evident from the fact that certain schematic formats of narrating the past are far more prevalent in some cultural and historical contexts than others, they are by and large manifestations of unmistakably social traditions of remembering.

Figure 1 The Versailles and Compiègne Plotlines

Progress

A perfect example of such a plotline is the general type of historical narrative associated with the idea of progress. Such a “later is better” scenario is quite commonly manifested in highly schematic “rags-to-riches” biographical narratives13 as well as in unmistakably formulaic recollections of families’ “humble origins.” It can likewise be seen in companies’ “progress reports” to their shareholders as well as in history of science narratives, which almost invariably play up the theme of development.

Yet the most common manifestation of this progressionist14 historical scenario is the highly schematic backward-to-advanced evolutionist narrative. It is quite evident, for example, in conventional narrations of human origins, which typically emphasize the theme of progressive improvement with regard to the “development” of our brain, level of social organization, and degree of technological control over our environment. Similarly, it is evident whenever modern, “civilized” societies are compared to so-called underdeveloped, “primitive” ones.15

As we can see in figure 2, such an unmistakably schematic vision of progressive improvement over time often evokes the image of an upward-leaning ladder. This common association of time’s arrow with an upward direction (and its rather pronounced positive cultural connotations)16 is quite crisply encapsulated in the title of Jacob Bronowski’s popular book and television series, The Ascent of Man,17 as well as in the conventional vision of the “lower” forms of life occupying the lower rungs of the “evolutionary ladder.”18

Such a highly formulaic vision of the past clearly reflects more than just the way some particularly optimistic individuals happen to recall certain specific events. Indeed, it is part of the general historical outlook of entire mnemonic communities. Though we normally regard optimism as a personal trait, it is actually also part of an unmistakably schematic “style” of remembering shared by entire communities.

Thus, as is quite evident from Horatio Alger’s and numerous other “rags-to-riches” versions of the so-called American Dream, many Americans, for instance, are much greater believers in the idea of progress than Afghans or Australian Aborigines. And as one can clearly tell from the general aversion of the working class to this idea,19 different historical outlooks are also associated with different social classes.20

Furthermore, as a brainchild of the Enlightenment, progressionism is a hallmark of modernity and has certainly been a much more common historical outlook over the past two hundred years than during any earlier period. Viewing history in terms of progress is an integral part of the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century philosophies of Marie Jean Condorcet, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Introduction The Social Structure of Memory

- 1 The Social Shape of the Past

- 2 Historical Continuity

- 3 Ancestry and Descent

- 4 Historical Discontinuity

- 5 In the Beginnings

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Author Index

- Subject Index