![]()

ONE

A Conversation in Rome

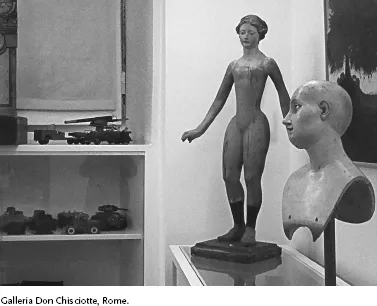

WHEN I ARRIVE at Giuliano’s gallery I often find him in the midst of making some sculpture in papier-mâché, sitting at his desk in the front, spreading wet strips of the Corriere della Sera over a rough form, in order to make what looks like a tall horse or an elongated human head. This is the Galleria Don Chisciotte, so it is not surprising that among the completed works scattered around the space there many versions of Cervantes’s hero—eerily elongated, stark and fragile, sometimes standing alone with his helmet and spear, or mounted, at a precarious angle, on the back of a paper Rocinante. There is also a staring, astonished king, a demon, and a cat with sawlike teeth. There is a wild-eyed Pinocchio figure with a thin, elongated nose, as well as a fierce, spike-bearded sculpture of Mangiafoco (fire-eater)—the impresario of the puppet company whose show Pinocchio interrupts, and who threatens to throw him on the fire to help cook his dinner. All are somewhat starved, solitary, yet immensely playful. I apologize to Giuliano for interrupting him in his work, but he is content to let the flour glue dry while we talk, holding a thin black cigarette in his hand.

I have walked here from nearby Piazza del Popolo, with its vast oval space and the fountain at its center, a huge obelisk—an ancient Roman prize from Egypt—surrounded by four granite lions spouting water. The piazza is just inside the walls of the old city, at the point where the ancient Via Flaminia begins, flanked on the east by the steeply climbing Pincian Hill, on top of which one sees the umbrella pines of the Villa Borghese. At the northern end of the piazza is Santa Maria del Popolo, one of the few early Renaissance churches still remaining in Rome. It is a place I know well, since, in a chapel just to the left of the apse, there are two paintings by Caravaggio that I often go to stare at, images of a grotesque martyrdom and a violent conversion. On the left wall of the chapel is a picture of Saint Peter being crucified upside down. You see the cross starting to be raised, hauled aloft by three straining workmen—one grasping the base, one tugging at it with a rope, one crouched down low with the main shaft on his shoulder. Peter leans forward and turns around, his strong neck and shoulders straining to give him a glimpse of those workers, resembling less a man in pain than someone rising from or falling back into sleep. Facing this image is the conversion of Saint Paul. It shows, close up, the persecutor of Christians fallen from his horse and lying on his back, arms rising up with ease toward a pool of light. Close by and looming above him, filling almost all the rest of the space, is the beautiful, immobile horse, whose hide is mottled white and brown and flooded with the same light as Paul, with a great hanging head that looks calmly at the ground. You look back and forth with increasing need, trying to find some relation between the two paintings, the movements up and down, the directions of the limbs, the curved form of Peter bending around to watch his crucifixion and the curved neck and head of the horse, looking down at Paul. They form a kind of magnetic field between them that keeps eye and body in motion, making gravity inescapable and yet a stranger sort of thing.

A hen’s foot of streets ushers you out of the piazza. The Corso, beautifully flanked by twin baroque churches, is the central toe, leading you down past Trajan’s Column to the gaudy expanse of the monument to Vittorio Emanuele, behind which are the ruins of the Roman forum. But to get to the gallery you take the street on the right, the Via Ripetta, and walk two blocks south to the corner of the Via Angelo Brunetti, where it is just to the right, number 21. I visited first because a friend told me the gallery had old puppets and toys for sale.

Many of the figures on display are small and simple marionettes from the nineteenth century, with metal control rods stuck through their heads and a few strings to move the arms and torso. You see them all mingled together, without regard for social distinction, kings, princesses, villains, peasants, clowns, devils, magicians, knights, giants, and pygmies. They hang along the walls, with their wide-staring eyes and small wooden hands, mildly or grimly distorted versions of the human, their costumes often showing marks of age. These works of popular artifice are less self-contained than more finished works of art, asking more than the eye of the viewer to make them live. In their stillness they are at once more intimate and more commonplace, impassive but needful, trying to appeal to some inner theater of sentiment, since there is no one to take them down from their hooks and improvise a show with them. (Puppets do not have thoughts, they are more like our thoughts, images of our thoughts, as if our minds were populated with remnants of the older, more clichéd stories that we manipulate and that manipulate us.) There are also nineteenth-century hand puppets, similarly diverse characters but with larger and more bluntly carved wooden heads, paint that is rubbed and stained, and shapeless costumes and arms empty of the hand that gives them life. These too have the wide staring eyes that seem inevitable in this tradition, looking out at you, demanding response but without sympathy, without interiority. Among them are many examples of Pulcinella, the Italian Punch, with his white clown’s costume and black, sharp-nosed mask.

Also on the shelves are some beautiful toy theaters—those paper cutout forms so popular in the nineteenth century, engraved and colored images of actual theaters with their elaborate prosceniums, curtains, and painted backdrops, as well as tiny paper figures in costume. Such theaters allowed children within their homes to restage and reinvent in a private space works played on the public stage, everything from Othello and Aida to Jack the Giant-Killer and Blue Beard. (Toy theaters fascinated the young Ingmar Bergman, among others. “This is the great magic. It will make your flesh crawl,” he says in documentary footage shot while he films a scene for the opening of Fanny and Alexander, a moment where a haunted child—Bergman’s alter ego—alone in an empty house, plays distractedly with his paper actors.) Old toys fill other glass cases in the gallery, most from the early and mid-twentieth century, variously German, Japanese, and American: metal windup cars, small mechanical trains running on narrow circles of track, wide-eyed monkeys that beat incessantly on tiny drums, metal clowns made to balance on their heads, ranks of windup motorcyclists, a child acrobat who twirls on a metal trapeze, and a tiny skirted dancer pirouetting on the back of a metal horse. They are not rare, handmade toys, but modest, industrially produced objects, made of cardboard, molded plastic, and lithographed tin, many stained or slightly rusted. They are relics, souvenirs of someone else’s childhood, and so a little senseless, out of phase, abandoned, waiting to be taken up, their fixed smiles carrying some other knowledge, oddly clairvoyant in their muteness. Part of the charm of these toys lies in their secret potential for motion, and the feeling that, different as they are in style and shape and origin, they are set together like members of a traveling circus, or the ad hoc family of a troupe of traveling players, waiting to perform. Yet another case in the gallery is inhabited by many variations of the perennial green-and-red figures of Pinocchio that you find in shops all over Italy, large and small, old and new. Those going back to the 1930s are virtually the same as modern ones, though there is a patina of age on them. They are members of a family of eternal children that must number in the hundreds of thousands—all with long, jointed limbs, blunt hands and feet, fixed smiles and eyes, conical green hats, and the pointed nose just long enough to recall its mysterious penchant for growing in response to lies and tales. None of them seem able to keep one another company.

Set out on other shelves are miniature carved cherubs and benignly smiling images of the infant Christ. Near them stand female figures made of wood, between one and two feet high, with outstretched arms, their heads and hands carefully carved and painted, but with their torsos and legs more roughly formed, like those of a crude marionette. They were made originally for use in private household devotions of Italian Catholics, intended to be dressed in the ornamental trappings of the Madonna or a female saint, and they make an eerie spectacle in their undressed state. Along with these relics of lay devotion you can see, in the glass cases, rank upon rank of tiny, painted leaden soldiers, figures belonging to many periods, many places, and many armies—figures in medieval armor and the garb of the Napoleonic Wars, figures from World War I and World War II, including soldiers of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Among these last are several figures of Hitler—at attention, with outstretched arm, or sitting in a staff car. They must once have belonged to a perfectly ordinary child.

The very lack of system in Giuliano’s collection is part of its appeal, even its historical and aesthetic intelligence. These objects evoke a mysterious population, relics of forgotten households, refugees from abandoned games, traces of all sorts of lost industries and forms of play, forms of worship, and forms of kitsch. Giuliano has arranged no scenes or tableaux among the toys on his shelves; it is left to the viewer to improvise familial and narrative relations among the different objects. More commonly in Rome, history is marked by ruins of temples and public baths, triumphal arches, huge stone heads and hands, and shapeless, overgrown masses of brick and concrete that seem like geological phenomena, such as the mausoleum of Augustus, which lies not far away down the Via Ripetta. Yet these smaller, homelier, no less secret things carry history in a different way, mark survival in a different way.

Giuliano de Marsanich is an old Roman, with a thin, worn, bearded face—full of fine wrinkles, a mobile, expressive face that by turns sharply displays delight, anger, sadness, and seriousness, often settling into an expression of quietness and reflection, punctuated by smiles and soft laughter. Someone said that he looks like a puppet, but in fact he looks more like Don Quixote. He has run the gallery since 1961, at first showing mostly the work of painters. Some have been well-established artists—Giorgio Morandi, Joan Miró, Gior gio de Chirico, Alberto Savinio (de Chirico’s interesting younger brother), and Salvador Dalí—but he always shows younger talent, his eye drawn especially to works of fantastic subject matter combined with precise, exquisite execution. In its earlier years, Giuliano also made the gallery a place where artists, actors, directors, and writers would gather in the evenings, the writers often reading from their work—a group that included Leonardo Sciascia, Giorgio Bassani, and Alberto Moravia, Giuliano’s first cousin. “Unforgettable evenings of poetry.” Many of his friends are dead, he often dreams of the dead, he tells me, gone not just years but decades.

The gallery has started to show paintings again—during my time in Rome in 2008 there is a fine show of commissioned works based on the theme of Don Quixote—but it is the puppets I have come to see, and about which I want to talk. Giuliano speaks about the puppets as one might talk about old friends or family members. They are objects of love, but also of a fascinated scrutiny. He gestures toward a new acquisition, a large unstrung and unclothed marionette from the nineteenth century, with its starkly jointed wooden limbs, its blunt torso and bald, painted head—shock eyes and red lips. He reflects on how, even lying still, it feels mysteriously alive to him, full of a frightening kind of presence; it does not need manipulators to gather a quantity of unsettling life. By contrast, he says, the simpler hand puppets, burattini, however stark their carving, remain nothing but lifeless bits of wood and cloth until they have the direct presence of a human hand inside their bodies. Giuliano knows the dramatic power of such inhuman actors, however, and frequently laments the decline of a serious popular puppet theater since the nineteenth century. Rome, in common with other cities in Italy, and Europe more generally, boasted a number of permanent theaters for marionettes at that time, along with many smaller traveling companies. Such theaters played anything that might be found on the human stage, melodramas such as The Count of Monte Cristo, Ruy Blas, Ernani the Bandit, and The Corsican Brothers, adaptations of Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, versions of Faust and Don Juan, operas by Mozart and Verdi, along with folk plays of Adam and Eve, the Nativity, the Passion, the Prodigal Son, or the temptation of Saint Anthony, and the great tradition of marionette plays based on chivalric epics such as Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. Simpler hand puppets, often playing on portable stages in street and square, showed rougher farces and improvised dramas, many starring the cudgel-wielding Pulcinella, a mocking, rebellious trickster, scheming at some kind of “wild justice.” Both the fixed and the moving stages displayed the puppet theater’s peculiar talent for humor and parody, the puppets’ will to insert their comic noses even into serious drama.

In an enthusiastic description of Roman marionette shows in his travel book Rome, Naples, and Florence (1826), Stendhal praises their spirit of acute and mordant satire. He likened their mocking force to the Roman tradition of the pasquinata, or pasquinade, a kind of poem that takes its name from a deformed, faceless fragment of ancient statuary nicknamed Pasquino, which stands in a small square in the old city, near Piazza Navona. Pasquinades were verse satires, often crude and demotic, and always anonymous, attacking the corruption, injustice, and stupidity of religious and political authorities. In a practice that began in the fifteenth century, these poems were pasted secretly at night to the base of the statue, making this scarred but dramatic piece of marble (which Bernini called the most beautiful statue in Rome) a mouthpiece for thoughts otherwise unspoken, or too dangerous to attach a name to. Puppets also have often been asked to say things or show things otherwise not permitted; it is a theatrical mode whose words and actions are more able to slip under the radar of official censorship, something too trivial to be taken quite seriously by the authorities (though in practice puppet theater could be just as subject to restriction as the theater of human actors). One thing that Giuliano likes in the puppets, I think, is that they form a kind of secret society, for all their bluntness and openness of mien, that they are heroes and victims of a hidden history of resistance to church and state. They chorus with the strongly anticlerical streak in him, common to many Romans. “I have a great antipathy toward the Vatican, a center of power, vicious, cruel, I hate the bishops, the cardinals, a terrible form of theater.”

It fits that a gallery for puppets and toys would take its name from Don Quixote, though Giuliano named his gallery long before it was devoted to showing these creatures. When I ask him about the mad knight, he says, “Don Quixote was a great marionette, no? a pure creature of the theater.” He is indeed a figure moved by the enchanter-puppeteer Cervantes, as well by those other humans he encounters, and by his own desire and imagination; he is often cruelly battered and tossed about, as puppets are, but survives to continue his quest. There is a nobility in the knight’s delusions as well as mockery, caught as the novel is between skepticism and mad faith, able to make one glimpse the madness of those who appear sane. In one episode Don Quixote mistakes puppets for living humans, making them more real (and himself more puppetlike) in cutting them to pieces. Giuliano tells me that he particularly loves the scene at the end of the novel where Sancho tries to convince the dying Alonzo Quixano, who has abandoned his quest, to take up the fantasy again.

Another ironic quester, Pinocchio, also comes up often in our conversations. This is not the saccharine Pinocchio of Walt Disney, but the darker figure shaped in the original tale, published by Carlo Collodi in 1881, which is something of an Italian obsession. Giuliano talks of Collodi’s puppet with familiar affection, as something that has long been part of his memory and imagination. Collodi himself—liberal journalist, Freemason, and gambler—intended to close his originally serialized fiction with the scene of the puppet Pinocchio hung up by his enemies, the Cat and Fox, when he refuses to give them his gold coins, but the public could not bear to let the puppet die, demanding that the story continue. There is a spirit of uncanny play and grotesquery in the book. Pinocchio in his actions is a charged, haunted thing, and the book’s satiric humor is joined to something rare in Italian writing, Giuliano suggests, “un mondo gotico”—a Gothic world—full of death and menace, shadow selves and doppelgängers, a world such as is more familiar in writings by Hoffmann, Hawthorne, or Poe. (Italians in general, he insists, have no understanding of the Gothic spirit.) In the book, any impulses of moral shame or even filial affection we find in Pinocchio are brief and intermittent. More frequently, Pinocchio becomes an incarnation of the dangerous spirit of the puppet, keeping faith with his origin in a piece of wood that otherwise might have been burned for warmth, even as he makes contact with wilder sources of life. His language attaches itself to the real unexpectedly, but always with mocking precision. As Giorgio Manganelli explores in his remarkable study Pinocchio: Un libro parallelo, the puppet often knows things he cannot know—nicknames, private histories, distant places—even as his words evoke the arbitrary, adhesive, empty truths of fantasy and human naming, the power of absent things. Yet Collodi’s novel always shows the puppet’s affinity for the world of ordinary objects, their melancholy and potential for harm.

Collodi’s wooden boy is indeed not a sweet, endearing thing. Throughout the book he is cowardly, impatient, and careless of others, a ready liar, often devious, but also headstrong and easily duped. Frequently beaten and abused—like Don Quixote, he always survives these attacks—Pinocchio is himself not a little given to violence. His immediate response to the criticisms of a talking cricket, for example, is to smash the creature against the wall with a mallet. Even in his subversiveness, Pinocchio is indeed, Giuliano reflects, something of a Fascist.

The comparison is not an idle one for an Italian of Giuliano’s generation (he was born in 1929). After many conversations, I am no longer surprised at how quickly Giuliano’s talk about puppets can shift into talk about Italian history and politics, especially the legacy of Mussolini. Both topics conjure up the same urgent fascination in him, bouts of anger and melancholy. As a young man in the 1950s and 1960s he was part of leftist intellectual and political circles, joining in succession various Socialist and Communist groups, even advocating militant political action, before becoming disenchanted with politics of all sorts (a disenchantment at once answered and emblematized by the chaos of objects in the gallery). This restless search was itself partly a reaction to having grown up with a father who was a member of the Fascist party and an uncle high up in Mussolini’s state. Mussolini remains a question mark. Giuliano speaks of Il Duce as “un pezzo di merda,” a coward and opportunist, something of a clown, a fat puppet. (There were laws banning puppet theater in Fascist Italy because, one contemporary speculated, “every puppet can put on Mussolini’s chin.”) Yet he wants to recall the power of Mussolini’s physical presence and of his rhetoric, the fascination he and his movement held for many inside and outside Italy. And while rehearsing the treacheries and violence of the Fascist state, he wants to keep in mind how much its power depended on the complicity of ordinary Italians—including some politically...