- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the passage of the Civil Rights Act, virtually all companies have antidiscrimination policies in place. Although these policies represent some progress, women and minorities remain underrepresented within the workplace as a whole and even more so when you look at high-level positions. They also tend to be less well paid. How is it that discrimination remains so prevalent in the American workplace despite the widespread adoption of policies designed to prevent it?

One reason for the limited success of antidiscrimination policies, argues Lauren B. Edelman, is that the law regulating companies is broad and ambiguous, and managers therefore play a critical role in shaping what it means in daily practice. Often, what results are policies and procedures that are largely symbolic and fail to dispel long-standing patterns of discrimination. Even more troubling, these meanings of the law that evolve within companies tend to eventually make their way back into the legal domain, inconspicuously influencing lawyers for both plaintiffs and defendants and even judges. When courts look to the presence of antidiscrimination policies and personnel manuals to infer fair practices and to the presence of diversity training programs without examining whether these policies are effective in combating discrimination and achieving racial and gender diversity, they wind up condoning practices that deviate considerably from the legal ideals.

One reason for the limited success of antidiscrimination policies, argues Lauren B. Edelman, is that the law regulating companies is broad and ambiguous, and managers therefore play a critical role in shaping what it means in daily practice. Often, what results are policies and procedures that are largely symbolic and fail to dispel long-standing patterns of discrimination. Even more troubling, these meanings of the law that evolve within companies tend to eventually make their way back into the legal domain, inconspicuously influencing lawyers for both plaintiffs and defendants and even judges. When courts look to the presence of antidiscrimination policies and personnel manuals to infer fair practices and to the presence of diversity training programs without examining whether these policies are effective in combating discrimination and achieving racial and gender diversity, they wind up condoning practices that deviate considerably from the legal ideals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Working Law by Lauren B. Edelman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226400761, 9780226400624eBook ISBN

9780226400938Part I

The Interplay of Law and Organizations

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is regarded as one of the most significant social reform laws ever passed in the United States. It held great promise for a nation in which, as Martin Luther King Jr. previsioned, people would be judged only by the content of their character.1 More than fifty years later, although considerable progress has been made, that dream has yet to be realized. In this book, I argue that an important reason for continuing racial and gender inequality in the workplace is that employers create policies and programs that promise equal opportunity yet often maintain practices that perpetuate the advantages of whites and males. Over time, organizational policies that symbolize diversity have become widely accepted indicia of compliance with civil rights laws, irrespective of their effectiveness. When we see company brochures that highlight their diverse workforces or university websites that emphasize their commitment to equity and inclusion, we tend to think of those organizations as fair and nondiscriminatory even though we know little about whether men and women of color and white women have equal access to management and professional positions or are subject to harassment that makes it difficult for them to succeed. We have become a symbolic civil rights society: one in which symbols of equal opportunity are ubiquitous and yet often mask discrimination and help to perpetuate inequality.

The widespread acceptance of organizational policies that symbolize equal opportunity, moreover, extends into the legal realm, where courts too often focus on the presence of organizational policies that signify nondiscrimination more than they attend to evidence that minorities and women face systematic disadvantages at work. In so doing, courts embrace and condone symbolic civil rights. In Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes,2 a case that illustrates this problem, the United States Supreme Court focused on a company policy banning sex discrimination more than on evidence that women were systematically denied advancement and training opportunities, paid less than men for similar work, steered into lower-paying jobs, subjected to a hostile work environment, and subject to retaliation if they sought to redress the alleged civil rights violations.

Betty Dukes, a fifty-four-year-old employee at a Walmart3 store in California, was the named plaintiff in a class action lawsuit that began in 2001 in the US District Court for the Northern District of California. In seeking to certify the largest class in US legal history, the plaintiffs provided evidence of widespread disparities in opportunities for women, offered statistical evidence showing that women were underrepresented in management and paid less than men, and presented expert testimony by sociologist William Bielby, who argued that Walmart’s corporate culture and discretionary personnel practices made it vulnerable to gender bias. The issue in determining class certification was whether there were common questions of law and fact such that the female employees could sue as a class rather than individually. In June 2004 the district court ruled in favor of class certification, and Walmart appealed. After multiple hearings at the federal appeals court, the full panel of eleven Ninth Circuit judges affirmed the district court’s class certification in February 2009 in a 6–5 vote, and Walmart appealed to the US Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower courts. In a 5–4 decision in 2011, with the justices divided along ideological lines, the Court ruled that the class action could not go forward and held that female employees would not be able to establish discrimination across all of Walmart’s roughly thirty-four hundred stores. In reaching the conclusion that there could be no common experience of discrimination, the majority opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, emphasized, “Wal-Mart’s announced policy forbids sex discrimination.”4 Thus, despite evidence presented by the plaintiffs that showed overwhelming statistical disparities based on sex (women held more than two-thirds of the low-level hourly jobs but only one-third of the management positions and, even when promoted, were concentrated at the lowest managerial level) and anecdotal evidence of sex discrimination by many managers, the presence of a formal policy banning sex discrimination was an important factor in the Court’s decision to shut down the class action case.

The Wal-Mart decision is an example of a phenomenon I call judicial deference, in which judges infer a lack of discrimination in part from the presence of organizations’ formal policies even when those policies are ineffective and fail to protect employees’ civil rights. The formal antidiscrimination policy that the Court deferred to is an example of what I call a symbolic structure, a policy or procedure that is infused with value irrespective of its effectiveness. Symbolic structures connote attention to law or legal principles, whether or not they contribute to the substantive achievement of legal ideals. Symbolic structures exist along a continuum from symbolic and substantive, meaning that they signal attention to law and are effective at achieving legal ideals, to merely symbolic, meaning that they are ineffective at achieving legal ideals but retain symbolic value. Many symbolic structures have some substantive effect, but often much less than courts assume.

My focus on symbolism is inspired in part by work in political science that calls attention to the political deployment of symbols as a means of ensuring the “quiescent acceptance of chronic inequality, deprivation, and daily indignities”5 and, in the context of law, as “powerful shapers of perceptions.”6 I argue in this book that societal acceptance of and judicial deference to symbolic structures, irrespective of their effectiveness, help to explain why race and gender inequality persist in the American workplace more than a half century after the passage of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.7

The Persistence of Race and Gender Inequality after Fifty Years of Civil Rights Legislation

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act ushered in a new era of civil rights legislation. Since its passage, many other civil rights laws mandating equal employment opportunity (EEO) have been enacted, including the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967,8 which prohibits employment discrimination based on age (over forty); the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,9 which expanded the power of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC); the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990;10 the Civil Rights Act of 1991;11 and the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993.12 In addition to federal laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, veteran status, and pregnancy, state and local EEO laws in some jurisdictions cover other types of discrimination as well, including discrimination on the basis of weight and sexual orientation.

Although most of my arguments apply to protected groups in general, I focus in this book on discrimination on the basis of race and sex because these forms of discrimination are so prevalent in the American workplace and are the most common types of discrimination alleged in discrimination complaints to the EEOC13 and in lawsuits alleging discrimination.14 I use the term minorities to refer to men and women who are members of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and the term women to refer to both women of color and white women. Although the phrase minorities and women is sometimes read to refer to minority men and white women, thus excluding women of color, I always mean to include women of color unless otherwise specified.

During its first fifty years, EEO law, along with social movement pressure and changing management practices, has sharply reduced overt discrimination, and there has been considerable improvement in the workforce status of minorities and women. Newspapers no longer run job ads for whites or males only, and minorities and women enjoy significantly greater representation in the workforce now than in the 1960s. Yet, as is revealed by the figures and the statistics cited below, substantial workplace inequality on the basis of race, sex, and other protected categories persists.

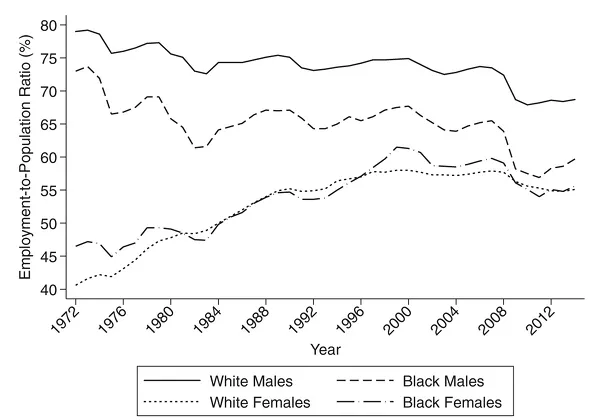

Figure 1.1 shows the employment-to-population ratio by race (blacks and whites only) and gender from 1972 to 2014.15 These data reveal a substantial reduction over time in overall inequality but also show that substantial differences still exist. Black females and males and white females continue to lag considerably behind white males in workforce participation. Most notably, while the gap between white and black males has remained relatively consistent over time, it is actually greater today than it was in 1972.

Figure 1.1. Employment-to-population ratio by race and gender, ages twenty and above, 1972 to 2014. Source: Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, (Unadjusted) Employment-to-Population Ratio—20 Yrs. & Over, series IDs LNU02300028, LNU02300029, LNU02300031, LNU02300032.

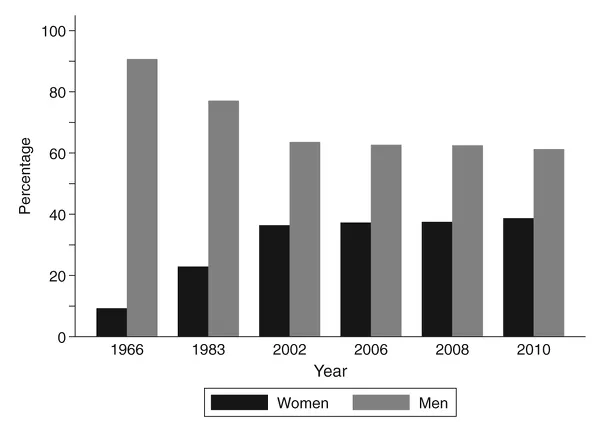

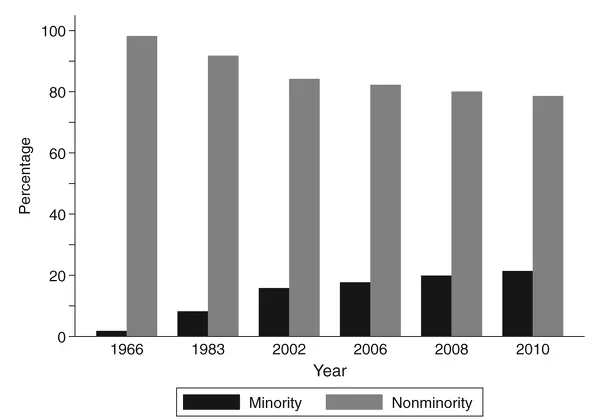

In addition to being underrepresented in the workforce as a whole, women and minorities are underrepresented in high-level positions. Figures 1.2 and 1.3 show that women and minorities, respectively, have gained representation among officials and managers among private firms with 100 or more employees but still lag far behind men and whites. As with overall representation in the workforce, women have made greater gains toward men in obtaining high-level positions than have minorities toward nonminorities. Moreover, minorities are still disproportionately represented among laborers and service workers, and women are still disproportionately represented among office and clerical positions.16

Figure 1.2. Officials and managers in US private sector, women versus men—1966, 1983, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2010. Source: Data from Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Job Patterns for Minorities and Women in Private Industry (based on EEO-1 reports).

Figure 1.3. Officials and managers in US private sector, minority versus nonminority— 1966, 1983, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2010. Source: Data from Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Job Patterns for Minorities and Women in Private Industry (based on EEO-1 reports).

Among all firms, in 2014 African Americans made up 11.4 percent of the total workforce but only 6.7 percent of management positions, and Hispanics made up 16.1 percent of the total workforce but only 9.1 percent of management positions.17 Females made up 46.9 percent of the total workforce but only 38.6 percent of management positions.18 Wage gaps for both minorities and women remain, including at management levels. Relative to their white male counterparts, African American males earned 75.8 percent as much, Hispanic males earned 68.6 percent, African American females earned 68.1 percent, and Hispanic females earned 61.0 percent.19 Females earned 82.5 percent of what their male counterparts earned in 2014; and in management professions, females earned only 77.5 percent of what male managers earned.20

Social scientists have documented systematic patterns of race and sex segregation in the labor market and within organizations.21 Women and minorities are disproportionately segregated into job categories with shorter mobility ladders, reduced access to job training, and fewer networking opportunities; are more likely to encounter glass ceilings; and generally receive lower pay than workers in job categories dominated by white men.22 In their book, Documenting Desegregation, Kevin Stainback and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey provided extensive documentation of sustained—and in recent years increasing—segregation on the basis of race and sex in the United States. They showed that from the mid-1960s until about 1980, segregation on the basis of race and sex declined. From 1960 to 1972, black men in particular saw marked improvement in their workforce position. From 1972 to 1980, both white and black women made substantial gains as well. The workforce position of white women continued to improve through about the year 2000, but progress for both black men and black women slowed after 1980.23

Beyond the statistics, scholars have identified continuing forms of discrimination that are less easily measured but nonetheless hinder the employment prospects of white women, minority men, and especially minority women. Employers’ reliance on social networks to find new employees tends to exacerbate segregation by encouraging women to go into traditionally female job categories and minorities to go into job categories with less potential for upward mobility.24 Seniority rules, transfer policies, and job-posting practices tend to preserve the segregation that occurs at the entry level.25 Tokenism, or small numbers of women or minorities in a workplace, hinders success by increasing harassment, caus...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- PART I. The Interplay of Law and Organizations

- PART II. Law in the Workplace

- PART III. The Workplace in Law

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index