- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this era of tweets and blogs, it is easy to assume that the self-obsessive recording of daily minutiae is a recent phenomenon. But Americans have been navel-gazing since nearly the beginning of the republic. The daily planner—variously called the daily diary, commercial diary, and portable account book—first emerged in colonial times as a means of telling time, tracking finances, locating the nearest inn, and even planning for the coming winter. They were carried by everyone from George Washington to the soldiers who fought the Civil War. And by the twentieth century, this document had become ubiquitous in the American home as a way of recording a great deal more than simple accounts.

In this appealing history of the daily act of self-reckoning, Molly McCarthy explores just how vital these unassuming and easily overlooked stationery staples are to those who use them. From their origins in almanacs and blank books through the nineteenth century and on to the enduring legacy of written introspection, McCarthy has penned an exquisite biography of an almost ubiquitous document that has borne witness to American lives in all of their complexity and mundanity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Accidental Diarist by Molly A. McCarthy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780226033358, 9780226033211eBook ISBN

9780226033495CHAPTER ONE

The Almanac as Daily Diary

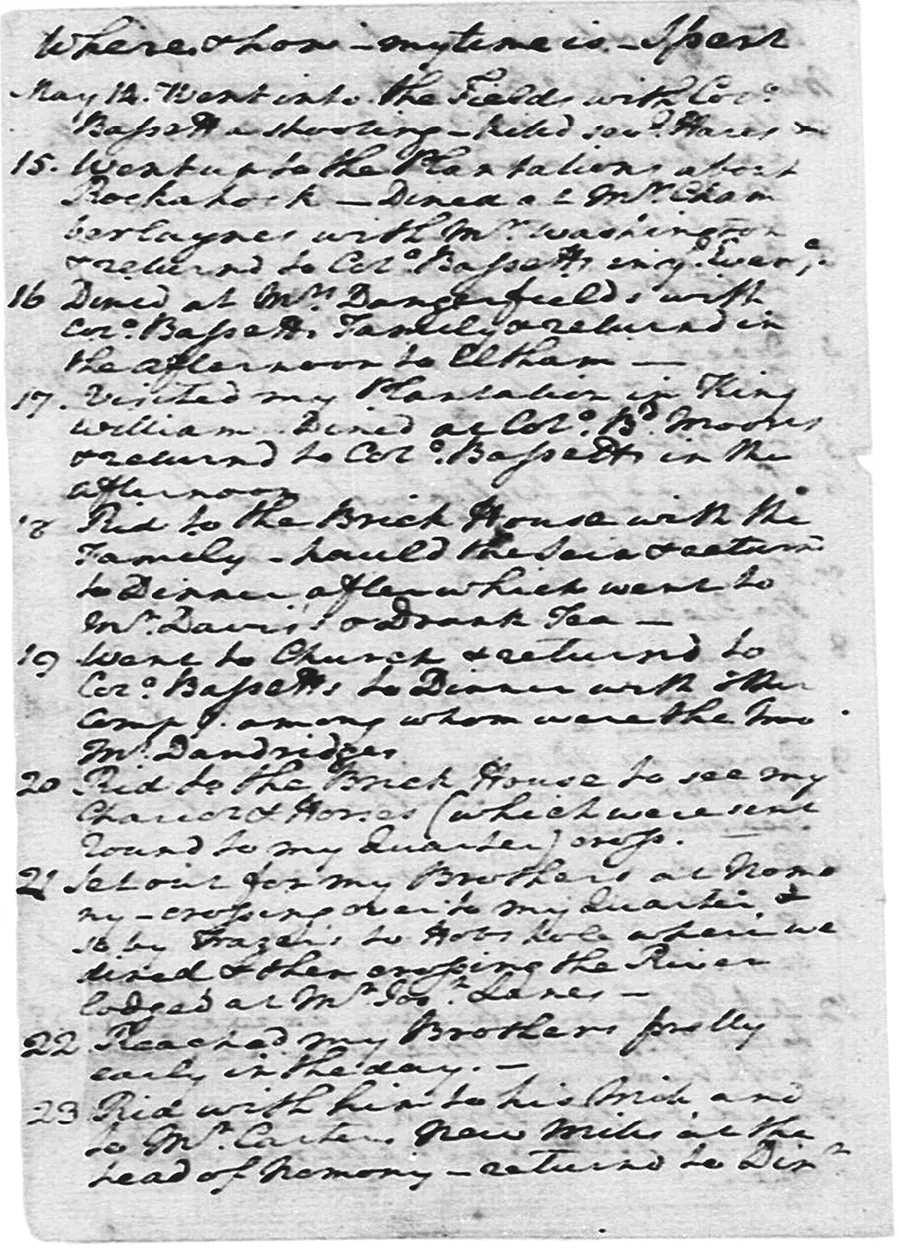

George Washington made a habit of writing at the top of each page in his diary the phrase “Where & how my time is Spent.” The motto, or mantra, certainly seems in character for a general revered for being methodical and disciplined. Yet the phrase reveals more than Washington’s idiosyncratic quest for order and self-control. His choice of words is symbolic and reflects the way an entire generation of early Americans conceived of and accounted for time. Time’s passage, for Washington and his contemporaries, remained tied to the days on the calendar more than the hands of a clock. Time proceeded a day at a time with few reasons to parse the days more finely than by forenoon, afternoon, and evening and little need to look beyond the present day to set future appointments. Washington’s phrase had more to do with marking the days as they passed, setting them in order and in time. But Washington could not do this without some help. For assistance, he looked to an almanac, or more specifically, to the pages of the Virginia Almanack.

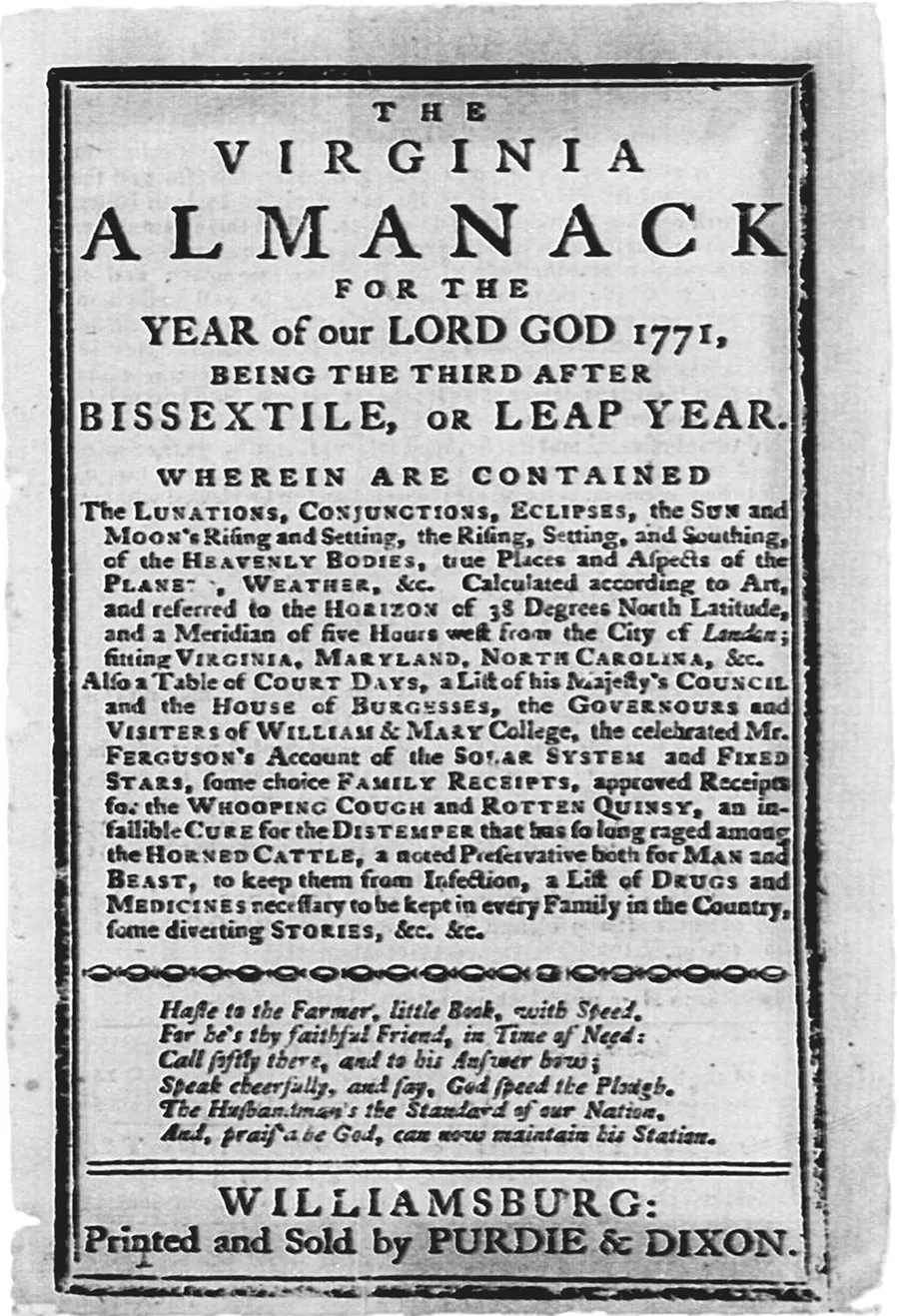

In fact, Washington’s diary and his annual were inextricably linked since Washington made his daily entries on blank pages sewn inside the Virginia Almanack. Washington’s diary and his almanac, then, were one and the same. While it is no secret that many of the Founding Fathers were avid diarists, few of their biographers have pointed out exactly what they were writing in. Thomas Jefferson, too, turned to an almanac for a diary, as did many colonists of his generation, both notable and unknown.1 Converting an almanac into a daily diary had roots in the Mother Country, and an almanac was among the first books the settlers of Massachusetts Bay imported into the colonies. When John Winthrop arrived in Salem aboard the Arbella in the spring of 1630, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay carried with him a draft of “A Model of Christian Charity,” the opening pages of his journal that would form the basis for his History of New England, and a copy of Allestree’s Almanac for 1620. A decade earlier, Winthrop’s father, Adam, had converted the annual into a diary for his grandson John Jr., so that he might learn the record-keeping habit when he came of age.2 Although Winthrop and his Puritan descendants rarely mentioned it, the almanac diary was far more common in British America than the diary of religious examination.3 It was the daily agenda of the colonial age. By the time Washington chose the Virginia Almanack to set down his daily whereabouts, the almanac diary had assumed a central role in how these early Americans marked their days and made sense of their world.

FIGURE 1.1. A page from George Washington’s diary inserted into his 1771 Virginia Almanack. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The almanac is key to understanding the full meaning behind Washington’s choice of words. The phrase was hardly accidental and informed by the distinctive conception of time the almanac reinforced. Scheduling events would be difficult, and nearly impossible, without its calendar. How else might Washington or other users know when to be somewhere on a certain day or at an appointed time? For those interested in increments smaller than the day, the astronomical data embedded in the calendar was equally critical since that was how those temperamental clocks remained calibrated. Sociologists have long acknowledged the importance of clocks and calendars for participating in social life. The almanac supplied the “means and ways to ‘time’” their behavior and provided diarists with a framework on which to inscribe their own experiences, moving both outward and inward simultaneously. That structure was much less compartmentalized than today with the “rhythmic beat” of most activities such as work and socializing more attuned to the day and the week than the hour or minute.4 If Washington needed to know what day it was or how many days before the next Sabbath, the calendar alone might suffice. Others achieved more benefits by adding a diary that ordered their past and brought structure to the present. Washington’s mantra indicated a need to order his experiences and exert some control over events that might otherwise feel disorderly and random.5 Customers would have to wait for products like the nineteenth-century pocket diary that, similar to today’s date books or blank calendars, allowed a user to look ahead and record future events in a preformatted, dated space. The timing in almanac diaries, for the most part, worked retrospectively.6

As prologue, this chapter explains how the almanac served as precursor and instigator of the daily planner. The daily planner would never have come about without the almanac. As America’s first best seller (as popular as the Bible), the almanac had a powerful influence on the way early Americans viewed time as well as money. It’s difficult to account for the great explosion in diary keeping and the rise of the daily planner in the nineteenth century without explaining the groundwork the almanac diary and its followers laid. From the perspective of its customers, the almanac accustomed them not only to a particular sense of time and its passage but also to a habit of recording that appeared matter of fact and abbreviated yet was rich with meaning. From the vantage point of the printers and booksellers hawking the popular annual, the almanac provided a reliable source of income year after year, even in the worst financial times.

Our modern-day view of the almanac is obscured by its folksy legacy: the Old Farmer’s Almanac. Still published annually, the periodical, founded by Robert B. Thomas in 1792, is most renowned for its weather predictions. As soon as the latest version of the Old Farmer’s Almanac hits newsstands every fall, broadcasters take to the airwaves, often highlighting the more outrageous or farfetched of forecasts, such as the year it foretold a “snowy winter” in Las Vegas.7 Although Americans might still peruse its pages to test its predictions or consult the quirkier columns, the almanac has become, for the most part, an antiquated conversation piece.

To Washington’s generation, the almanac was neither quaint nor folksy. America’s first president would have a difficult time accepting the almanac’s fall from grace, because for him, and for every colonist who came before him, the almanac was everything. It told him the time, calculated the interest on his loans, directed him to the nearest inns, and entertained him with its poetry. Before even acknowledging its role as a diary, Washington recognized the almanac as an indispensable calendar and local guide. More than many early newspapers, almanacs were a font of local information. They provided readers with the kind of facts needed to negotiate the geographic and commercial terrain of early America. A colonist might turn to a newspaper in search of an advertisement for books or assorted “English Goods,” but he’d turn to his almanac to consult a list of roads from Boston to New York or New York to Philadelphia. He might also find there, when the region’s courts were in session, a list of local officials, coach fares, and currency conversion tables.

The almanac enjoyed a status in early America unparalleled by any book, except the Bible. Every colonial household was sure to have an almanac hanging on a peg by the hearth.8 Washington would have agreed with the author who cautioned his customers about the dangers of doing without: “A person without an almanac is somewhat like a ship without a compass; he never knows what to do, nor when to do it.”9 It’s the same feeling someone a century later might have experienced without his pocket watch. Even though that analogy may seem farfetched, many eighteenth-century Americans considered the almanac, not the clock, the authority on time. Take away the interest tables, the essays, the recipes, and other features publishers added over time, and the four- by six-and-a-half-inch crudely stitched pamphlet was—at its most basic level—a calendar.

The almanac provided a system, a form where none existed. It allowed men such as Washington to fill in the blanks rather than make up something entirely on his own. Just as we mark up our calendars today, write out a grocery list, or balance a checkbook, there is a satisfaction that comes with getting things down on paper. However, in this case the uses were prompted by the almanac’s features, many of which came down to time and matters of the pocketbook: listing expenses, recording loans, noting debts, or figuring out how much money until payday.

It’s no wonder the almanacs that survive are so fragile. They look as if they had been carried around in a breast pocket or thumbed to near disintegration. Many scribbled sums or recorded a settled debt in the margins. In an advertisement placed in the Virginia Gazette on December 12, 1777, a subscriber offered a $10 reward to anyone who might find his “small red pocket book containing a blank almanack, and the following bills, viz. One twelve pounds of the James river bank, one eight, one six and one five dollar bill, a four and one shilling bill with two parcels of needles.”10 Almanacs became vital personal accessories, as crucial as a hat or coat in foul weather. They were cheap, portable, and compact, a convenient accoutrement for the merchant about town as well as a farmer in the woods.

Booksellers in England had promoted the almanac’s suitability as a diary for more than a half-century before Adam Winthrop modeled one for his grandson. From a production standpoint, there were a few methods almanac makers used to aid customers in converting their pamphlets into diaries. If paper was plenty, publishers simply inserted a blank page opposite the calendar for each month, known in the business as “interleaving.” As early as 1565, Englishman Joachim Hubrigh introduced A Blanke and Perpetuall Almanack “designed primarily for the reader to note debts, expenses and other ‘things that passeth from time to time (worthy of memory to be registered).’” Imitators soon followed, with Evans Lloyd adopting another method with his 1582 almanac by offering account pages already “marked off in columns headed ‘L.s.d.’” To save paper others reserved a column on each calendar page for personal notes, though, understandably, it allowed for the scantest of insertions.11 Such almanacs, often called “Blanckes,” offered space opposite the calendar pages for the owner to note debts, expenses, and other “things that passeth from time to time (worthy of memory to be registered).”

For the most senior Winthrop, the last directive meant noting who happened to be preaching, as is evident from the following lines lifted from the diary pages of Winthrop’s copy of Allestree’s Almanack:

March 8. The Assises at Bury, Mr. Muninge preached before the Juges.

March 15. Sr. Jo. Deane & my lady dined wth us.

March 25. The year 1620 beginneth.

Aprill 17. Mr. Rogers of Dedham preached at Carsey.

May 9. Mr. Birde preached at B. & Mde Bacon came to Groton.

June 18. Mr. Smyth of ye K. Colledge preached in Groton. My Cosen Jeremy Raven preached at Boxforde on Sonday in the afternoone.12

For others, it meant recording the routines of one’s profession, whether as preacher, farmer, or merchant. Here are the events farmer Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, chose to memorialize in February 1713/4:

Thursd 18 fair. I was at home al day Presing hay. windy.

fryd 19 fair. I was at home Screwing hay al day.

Saturd 20 fair. I was at home Pressing hay al day.

Remarkably, Hempstead continued in similar fashion for another forty years.13 Such practices followed the day’s conventions and were influenced by the contents of the almanac itself. What someone recorded in his almanac was not so much determined by his personality as the dictates of a formula that was so predictable some almanac makers poked fun at their customers’ entries. One London publisher advertised a 1663 almanac with a “diary” already printed inside with notes such as “the red cow took bull,” “My son John born,” and “The black cat caught a mouse in the barn,” mocking the plain style of the typical diarist.14 Few customers appeared to care about what publishers thought of their entries since hundreds of enthusiasts followed Winthrop’s lead.

FIGURE 1.2. The title page of George Washington’s Virginia Almanack, the almanac he routinely chose for his diary. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By the time of America’s founding, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson preferred copies of the Virginia Almanack in which to record their daily memoranda. When Washington arrived in Philadelphia in the spring of 1787 without his diary, he wrote his nephew at Mount Vernon and asked for its swift return “under good strong paper cover, sealed up as a letter.” Just in case his nephew did not know where to look, Washington added: “It will be found, I presume, on my writing table.” For Washington, his almanac was critical to his sense of well-being, an essential tool that tracked his daily expenses and the events of his public and private life. Washington, himself, acknowledged as much with his now familiar motto: “Where & how my time is Spent.”15 Nevertheless, even though we might like to think Washington’s diaries more weighty or lofty than those of his contemporaries, his annotated almanacs followed a similar pattern. In the summer of 1771, his almanacs were suffused with the business of running his large estate:

July 1. Rid into the Neck to my Harvest People, & back to Dinner. Mr. Robt. Rutherford came in the Afternoon & went away again.

2. Rid to Harvest Field in the Neck & back to Dinner.

3. Rid to the Harvest Field in the Neck by the Ferry & Muddy hole Plantations. In the Afternoon Mr. Jno. Smith of Westmoreland came here.

4. At home all day with Mr. Smith. In the Afternoon Jno. Custis came.

5. Mr. Smith set out after breakfast on his journey to the Frederick Sprgs. In the Afternoon I rid to the Harvest Field in the Neck.

6. Writing the forepart of the day. In the afternoon Rid to Harvest Field at Muddy hole.16

As formulaic and repetitive as Joshua Hempstead’s entries decades earlier, Washington’s record keeping was not unique. One needed to look especially hard to find anything that might distinguish his daily register from the norm, and only if one knew how to read between the lines. For instance, later in the month of July, Washington recorded simply “I set out to Williamsbur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Almanac as Daily Diary

- 2. The Birth of a Daily Planner

- 3. The Profits of an Abbreviated Self

- 4. Making a Diary Standard

- 5. The Daily Planner Meets the Adman

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index