eBook - ePub

Unfreezing the Arctic

Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In recent years, journalists and environmentalists have pointed urgently to the melting Arctic as a leading indicator of the growing effects of climate change. While climate change has unleashed profound transformations in the region, most commentators distort these changes by calling them unprecedented. In reality, the landscapes of the North American Arctic—as well as relations among scientists, Inuit, and federal governments— are products of the region's colonial past. And even as policy analysts, activists, and scholars alike clamor about the future of our world's northern rim, too few truly understand its history.

In Unfreezing the Arctic, Andrew Stuhl brings a fresh perspective to this defining challenge of our time. With a compelling narrative voice, Stuhl weaves together a wealth of distinct episodes into a transnational history of the North American Arctic, proving that a richer understanding of its social and environmental transformation can come only from studying the region's past. Drawing on historical records and extensive ethnographic fieldwork, as well as time spent living in the Northwest Territories, he closely examines the long-running interplay of scientific exploration, colonial control, the testimony and experiences of Inuit residents, and multinational investments in natural resources. A rich and timely portrait, Unfreezing the Arctic offers a comprehensive look at scientific activity across the long twentieth century. It will be welcomed by anyone interested in political, economic, environmental, and social histories of transboundary regions the world over.

The author intends to donate all royalties from this book to the Alaska Youth for Environmental Action (AYEA) and East Three School's On the Land Program.

In Unfreezing the Arctic, Andrew Stuhl brings a fresh perspective to this defining challenge of our time. With a compelling narrative voice, Stuhl weaves together a wealth of distinct episodes into a transnational history of the North American Arctic, proving that a richer understanding of its social and environmental transformation can come only from studying the region's past. Drawing on historical records and extensive ethnographic fieldwork, as well as time spent living in the Northwest Territories, he closely examines the long-running interplay of scientific exploration, colonial control, the testimony and experiences of Inuit residents, and multinational investments in natural resources. A rich and timely portrait, Unfreezing the Arctic offers a comprehensive look at scientific activity across the long twentieth century. It will be welcomed by anyone interested in political, economic, environmental, and social histories of transboundary regions the world over.

The author intends to donate all royalties from this book to the Alaska Youth for Environmental Action (AYEA) and East Three School's On the Land Program.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unfreezing the Arctic by Andrew Stuhl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Dangerous: In the Twilight of Empires

Imagine the village of Kittigaaryuit in 1861 (figure 1). There, on a beach at the mouth of the Mackenzie River, perched the largest known settlement of Inuit in the North American Arctic. Up to one thousand Kittigaaryungmiut—ancestors of today’s Inuvialuit—sustained an elaborate community for half a millennium. They built semisubterranean houses out of driftwood and insulated them with the tundra’s thick sod. During short but vibrant summers, hunters pooled labor and ingenuity to take beluga whales from the Beaufort Sea. They drove the animals into bays between the river and the ocean, using shallow draft kayaks designed to be easily carried, yet strong enough to withstand incessant waves. In the dark days of winter, they invented games and rituals—all meant to keep mind and muscles fit—and hammered out a system of governance through conversation and dispute resolution.1

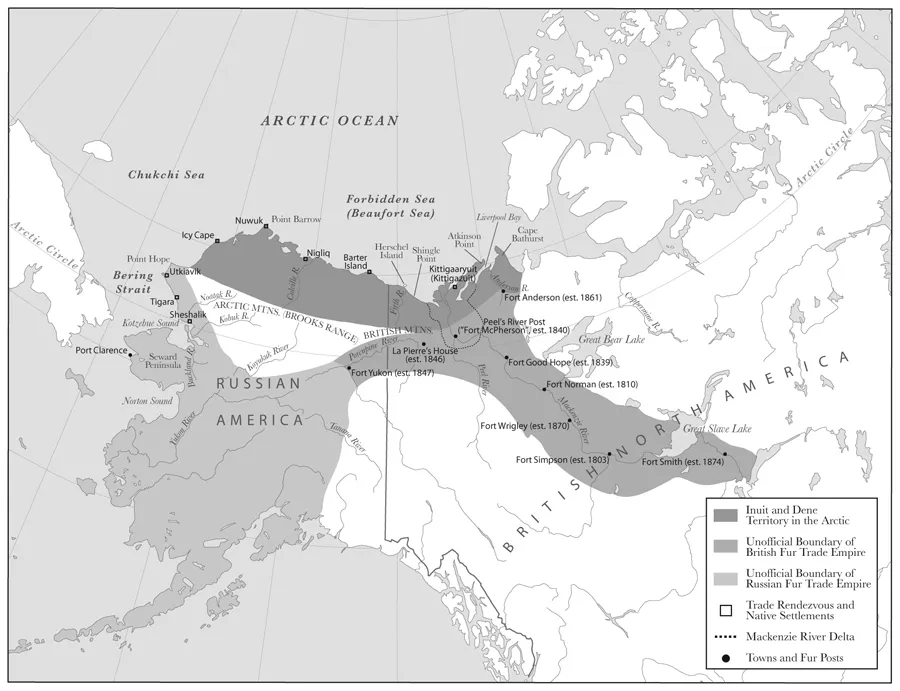

FIGURE 1. The western Arctic in 1861. Russian and British fur trading activities were consolidated around the Bering Strait and the Mackenzie River. Inuit living along the Beaufort Sea coast negotiated these empires and stemmed their northward expansion. Map by Morgan Jarocki.

To an untrained eye, Kittigaaryuit might look like highly localized adaptation. It could serve as an example of Inuit living according to what their immediate surroundings provide, however harsh and unforgiving. But when we look again, with a bird’s-eye view, we see holes in that theory. Kittigaaryuit was one of a string of Inuit settlements draped across the rim of northwestern North America in the middle of the 1800s. Far from isolated or self-sufficient, these places depended upon an immense corridor of economic exchange, itself under threat and supported by two world superpowers—the Russian and British empires (figure 1). Across the Bering Strait, Russian American Company traders provided manufactured goods, like firearms and ammunition, to Siberian and Alaskan Inuit for fox, beaver, and sometimes reindeer. Their British counterparts, the Hudson’s Bay Company, also desired access to Inuit country but could penetrate only as far north as Fort McPherson, several hundred miles south of Kittigaaryuit. At rendezvous points on Alaska’s Arctic slope, Inuit from the Bering Strait region met Inuit from along the coast—from as far west as Kotzebue, Alaska, and as far east as Kittigaaryuit. Here, Russian-made products moved to coastal Inuit in exchange for seal oil and whalebone. Native northerners on the Beaufort Sea coast thus funneled the goods of two different empires toward their subsistence while preventing either from encroaching upon their territories.2

Now, hold on to this image of Kittigaaryuit as we fast forward to 1898. The place pales in comparison. The buildings remain, but they are shells of their former selves. Rarely occupied, their supporting beams have been scavenged to erect graveyards. Scores of Inuit fell victim to a series of devastating epidemics over the turn of the twentieth century. Inuit still move through this place, but they do not stay long. They are en route to another settlement called Herschel Island, just offshore from today’s Yukon Territory. There they find the flow of goods and equipment that once sustained them, though a new imperial force has redirected and commanded it. With vessels that dwarfed Inuit kayaks, yet performed a similar function, American whalers sought the fat deposits and baleen of the bowhead whale. They transported these animal parts—themselves storehouses of nutrients accumulating in the Arctic ecosystem—to San Francisco for rendering into commodities that greased the machinery and pockets of urbanizing, industrial nations. Whalers helped convert marine life into illumination for factory workers, lubrication for power looms, and even fashionable corsets for ladies in Paris and London. In return, whalers brought their germs to the Arctic, as well as their flour and their rifles. Whalers traded all of these things with Inuit, transforming life on the Beaufort Sea coast.3

The American whaling industry triggered a sea change in Arctic history. Not simply because of the human and environmental displacements that followed in its wake, but because it set off a century of intervention, transformation, and scientific attention in the far north. To see how this could be so, we must examine movements within and across the Arctic at the close of the 1800s, like those witnessed in two scenes at Kittigaaryuit. Standard histories of this period often miss this action, focusing instead on political deal-making in Ottawa and Washington—think “Seward’s Folly”—or the exploits of British naval officers in search of the Northwest Passage. While these events shaped the north, their influence came at a distance and mattered little to the future of the Arctic—according to Native northerners, at least. In Inuvialuit historical accounts, the coming of whalers, or Tan’ngit (outsiders), marks the shift between a traditional period (1300 to 1800) and the era of land claims agreements and climate change (1970s to now). That is, commercial whaling spawned colonialism in the north and thus provides the beginning of the backstory for modern global warming and globalization. In the view from the top of the world, British explorers and federal bureaucrats, those who achieved so much fame in Euro-American accounts of the past, left “little lasting impression” on the Arctic.4

As we follow scientific itinerants, we come to see the two versions of Kittigaaryuit in a different light. By the mid-1890s, the sun had set on Russian and British imperialism in northern North America, while the stars of the United States and Canada had risen. Whether in perpetual darkness or under the midnight sun the Arctic sat always in the twilight of empires.

THE SKINS AND SAMPLES OF AN EARLIER AGE

Furs were the “black gold” in a preindustrial era of global trade. The skins of beaver, muskrat, and fox linked consumers and fur frontiers across the continents. The opening of New World fur territories in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had tilted the global distribution of wealth and power toward North America. This shift accelerated in the nineteenth century, in part through the opening of western Arctic fur grounds, which boasted a stock of fur-bearing creatures unrivaled in Europe. In an effort to control the extraction and circulation of furs from Arctic land, Russian, British, and indigenous nations confronted one another over the end of the 1800s.5

The Hudson’s Bay Company (hereafter HBC or the Company) wanted to tap the value of the Arctic and drain it via the Mackenzie River. The Company set up fur trading posts along more than 1,000 miles of the river by 1840. In that year, it opened the Peel River post, known today as Fort McPherson. Traders primarily engaged Dene First Nation communities nearby, but soon attracted Inuit living along the Yukon coast, in the Mackenzie Delta, and between the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers, to the east. The value of the Inuit trade grew over the 1850s, from 100 British pounds in 1854 to 1,000 pounds in 1858. In response, Company officers began to curry favor with Inuit, providing guns, ammunition, and tobacco at their request. These signs of encouragement convinced the chief factor of the Mackenzie District, James Anderson, to scout for a post situated squarely in Inuit territory. He called on Roderick MacFarlane, who journeyed to Anderson River in 1857 (figure 1).6

MacFarlane’s experiences on the Anderson River provide a first reference point for the profound changes in the Arctic over the second half of the 1800s. A Scot who joined the Company as an apprentice clerk at nineteen years old, he earned the rank of manager after two years managing trade at others posts in the Mackenzie District. His efforts in opening up Inuit fur country in the 1860s linked him to a constellation of power in North America, one that shifted substantially with the arrival of commercial whaling to the Beaufort Sea by the start of the 1870s.7

The fate of the Anderson River post—the Company’s first on the tundra in the western Arctic—suggests both the possibilities and obstacles of imperialism in the mid-1800s. After his initial reconnaissance of the Anderson River, MacFarlane wrote a glowing review of the fur resources of the country. The region, he concluded, boasted a large Inuit population, a suitable river for transportation, and abundant driftwood for fuel and shelter. After reviewing MacFarlane’s recommendations, the North American director of the Hudson’s Bay Company approved the construction of Fort Anderson in 1861. Over the next three years, MacFarlane reported increasing returns, with fox pelts bringing over 1,000 British pounds in 1864. By 1866, however, the Company shut the post down. Because the Anderson River was not part of the infrastructure-rich Mackenzie River valley, the Company struggled to administer it. An outbreak of distemper killed sixty-four sled dogs, which hampered already strained communication and transportation between Fort Anderson and the chain of posts that connected it to London. The end of the fort in 1866 thus foreshadows the combination of human and nonhuman forces that underpinned control over the Arctic for centuries to come.8

Despite MacFarlane’s failures, or perhaps because of them, the Arctic earned a lasting place in circles of professional science. At the most remote location in the Company’s system, MacFarlane had an unparalleled opportunity to collect materials from a landscape and culture not known by budding research communities. Between 1854 and 1866, MacFarlane contracted a scientific “fever,” leveraging his seasonal interactions with Inuit and Dene trappers to collect specimens. In one five-year period at Fort Anderson in that span, he sent more than five thousand artifacts to the newly built Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.9

This alliance between MacFarlane and the Smithsonian was not uncommon in North America at the time. Like it supported science in the US West, the Smithsonian supported Arctic science with zeal, employing those already living in the far north as collectors. Its first curator, Spencer Baird, outfitted his Hudson’s Bay Company team with dissecting kits, microscopes, pocket compasses, revolvers, opera glasses, and mosquito nets. In turn, Company men induced Inuit and Dene trappers to collect for them, providing American-made goods like handkerchiefs, jewelry, textiles, and the most prized item—double-barreled shotguns—in exchange for the skins of birds, bears, moose, and caribou. Baird also created user-friendly checklists for field-workers, like his “Directions for Collecting, Preserving, and Transporting Specimens of Natural History,” so that his Company workers, regardless of their training, could contribute to science in an orderly fashion. Zoological collecting had long been conducted out of curiosity, with a fascination for the bizarre. In enlisting northerners with concrete guidelines, Baird sought to introduce an organized and systematic process of data collection and enfold the Anderson River—a place out of reach to the Company—into the grasp of the natural history museum. Between 1859 and 1867, more specimens left northern British North America destined for the Smithsonian than had ever left the territory for European museums.10

MacFarlane was not a prolific writer, but his collections in some ways speak for themselves. A recent report by a team of museum scholars and Inuvialuit resource specialists described its contents as including “a full range of skin clothing and bags; hunting and fishing gear; domestic tools, personal jewelry, and a wide range of pipes; carving tools and artworks; a model umiat (boat), sleds and kayaks.” These objects were crafted locally but showed evidence of vast trade networks, which, for museum curators, now demonstrate “the vibrant, land-based lifestyle of the local people.” According to Stephen Loring, who has reviewed letters between MacFarlane and Spencer Baird, Inuit in the region were well versed in trading relationships and used MacFarlane’s presence to their advantage. “Already knowledgeable about the trading economy,” Loring notes, “MacFarlane’s Inuvialuit collectors took payment for the collections acquired on behalf of the Smithsonian in a wide array of non-Native commodities including clothing, tools, tobacco, and even guns.” As they worked together to skin the tundra, it seems both scientists and Inuit took samples from each other.11

THE NATURE OF IMPERIAL FRUSTRATION: ANTAGONISTIC NATIVES AND ILLEGIBLE LANDS

MacFarlane’s work deserves more interpretation, because even without a corpus to his name, he projected a powerful representation of the north. His Arctic natural history was a by-product of a mutually beneficial flow of material goods between Inuit trappers on one hand and British and Russian fur traders on the other. Yet this flow of goods induced fear in Russian and British fur companies as each vied for total control of Inuit lands, but failed to attain it. British audiences grew accustomed to stories of the dangerous Arctic. Its bone-chilling climate, extreme stretches of light and dark, and notoriously “barren” landscape had all vexed British naval officers in search of a Northwest Passage during the mid-1800s. MacFarlane’s scant written material and sketches added another element to these treacherous conditions: in his mind, Arctic indigenes were equally as hostile as the physical environment.

In 1891, Roderick MacFarlane published a summary of his 1857 journey down the Anderson River in the Canadian Record of Science. He tempered his optimism about the natural resources of the Anderson River area with his interactions with Dene and Inuit. MacFarlane traveled with an Inuit “chief” between the lower stretch of the river and a larger camp of Inuit families stationed at its mouth in Liverpool Bay (figure 1). Here, a fleet of Inuit canoes and kayaks overtook his party, which, according to the British fur trader, immediately displayed their intent to engage in battle. “Seven guns were held up to intimate to us that they were as well armed as ourselves,” MacFarlane wrote. He abandoned negotiations with these coastal Inuit, deciding to ditch his boats and walk seven days back to his camp upriver to avoid further confrontation. With similar expedience, he blamed this altercation on historic Inuit-Dene tensions around the fur trade. He did not acknowledge, however, that extending the Hudson’s Bay Company’s reach northward to the Arctic coast surely agitated Native northerners and their trading networks.12

This chronicle of events repeats a well-worn trope within Hudson’s Bay Company lore about the Heroic Fur Trader and the Hostile Natives. In 1771, Samuel Hearne had traveled down the Coppermine River with Dene guides, hoping to initiate trade relations with the Inuit living near the Coronation Gulf. According to Hearne, his Dene guides ambushed a party of Inuit, murdering twenty men, women, and children. In 1799, Duncan Livingston attempted to replicate Alexander Mackenzie’s 1789 journey down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean. After meeting a group of Inuit below Arctic Red River, Livingston’s entire crew was apparently killed. Hearne and Livingston’s experiences became legend, preserved in accounts that circulated throughout the Company for the next seven or eight decades. MacFarlane’s representation of the western Arctic, then, fit into a well-defined set of representations and interventions under British imperialism in northern North America.13

With the frame of these existing Company stories, Mac...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Note on Terminology

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- EPILOGUE

- Acknowledgments

- Archival Collections

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index