- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

There is nowhere else in the world quite like Chungking Mansions, a dilapidated seventeen-story commercial and residential structure in the heart of Hong Kong's tourist district. A remarkably motley group of people call the building home; Pakistani phone stall operators, Chinese guesthouse workers, Nepalese heroin addicts, Indonesian sex workers, and traders and asylum seekers from all over Asia and Africa live and work there—even backpacking tourists rent rooms. In short, it is possibly the most globalized spot on the planet.

But as Ghetto at the Center of the World shows us, a trip to Chungking Mansions reveals a far less glamorous side of globalization. A world away from the gleaming headquarters of multinational corporations, Chungking Mansions is emblematic of the way globalization actually works for most of the world's people. Gordon Mathews's intimate portrayal of the building's polyethnic residents lays bare their intricate connections to the international circulation of goods, money, and ideas. We come to understand the day-to-day realities of globalization through the stories of entrepreneurs from Africa carting cell phones in their luggage to sell back home and temporary workers from South Asia struggling to earn money to bring to their families. And we see that this so-called ghetto—which inspires fear in many of Hong Kong's other residents, despite its low crime rate—is not a place of darkness and desperation but a beacon of hope.

Gordon Mathews's compendium of riveting stories enthralls and instructs in equal measure, making Ghetto at the Center of the World not just a fascinating tour of a singular place but also a peek into the future of life on our shrinking planet.

But as Ghetto at the Center of the World shows us, a trip to Chungking Mansions reveals a far less glamorous side of globalization. A world away from the gleaming headquarters of multinational corporations, Chungking Mansions is emblematic of the way globalization actually works for most of the world's people. Gordon Mathews's intimate portrayal of the building's polyethnic residents lays bare their intricate connections to the international circulation of goods, money, and ideas. We come to understand the day-to-day realities of globalization through the stories of entrepreneurs from Africa carting cell phones in their luggage to sell back home and temporary workers from South Asia struggling to earn money to bring to their families. And we see that this so-called ghetto—which inspires fear in many of Hong Kong's other residents, despite its low crime rate—is not a place of darkness and desperation but a beacon of hope.

Gordon Mathews's compendium of riveting stories enthralls and instructs in equal measure, making Ghetto at the Center of the World not just a fascinating tour of a singular place but also a peek into the future of life on our shrinking planet.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ghetto at the Center of the World by Gordon Mathews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780226510200, 9780226510194eBook ISBN

9780226510217ONE

Place

Introducing Chungking Mansions

Chungking Mansions is a dilapidated seventeen-story structure full of cheap guesthouses and cut-rate businesses in the midst of Hong Kong’s tourist district. It is perhaps the most globalized building in the world. In Chungking Mansions, entrepreneurs and temporary workers from South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and across the globe come to seek their fortunes, along with asylum seekers looking for refuge and tourists in search of cheap lodging and adventure. People from an extraordinary array of societies sleep in its beds, jostle for seats in its food stalls, bargain at its mobile phone counters, and wander its corridors. Some 4,000 people stay in Chungking Mansions on any given night. I’ve counted 129 different nationalities in its guesthouse logs and in my own meetings with people, from Argentina to Zimbabwe, by way of Bhutan, Iraq, Jamaica, Luxembourg, Madagascar, and the Maldive Islands.

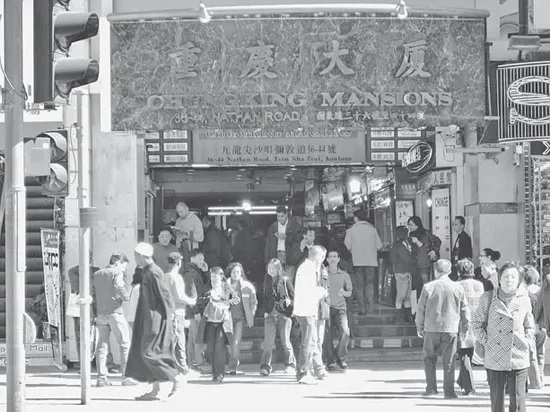

Chungking Mansions is located on the Golden Mile of Nathan Road, famous, according to the guidebooks, for “its ability to suck money from tourists’ pockets.”1 If you approach Chungking Mansions from across Nathan Road, you will see a row of glitzy buildings towering on the other side of the street bearing an array of stores, including a Holiday Inn, many electronics places, several entrances to shopping arcades, a number of fashionable clothing outlets, a couple of steak houses, and several bars. This looks like the Hong Kong of postcards, particularly if you approach in the evening and are bathed in the gaudy sea of neon that Nathan Road is famous for. However, in the midst of these fancy buildings is one that looks plainer, more disheveled and decrepit. Its lower floors, seen from across the street, hardly seem part of the building since they too are fancy shops and malls, physically part of the building but inaccessible except from outside and a world away. But then, in the middle of these stores, you see a nondescript, dark entrance that looks like it belongs somewhere else. As you cross Nathan Road on a butterfly crosswalk and draw closer to this entrance, you will notice that the people standing near the entrance to this building don’t look like most other people in Hong Kong, certainly not like the throngs of shoppers elsewhere on Nathan Road. As you enter the building, if you are Chinese, you may feel like a member of a minority group and wonder where in the world you are. If you are white, you might instinctively clutch your wallet while feeling trepidation and perhaps a touch of first-world guilt. If you are a young woman, you may feel, very uncomfortably, a hundred pairs of male eyes gazing at you.

If you approach Chungking Mansions from the same side of Nathan Road walking from the nearest underground MTR railway exit on Mody Road, just around the corner from the building (see map on p. 6), you will get a somewhat fuller introduction to the place. You will first see a 7-Eleven that in the evenings may be full of Africans drinking beer in its aisles and spilling outside its entrance. You may also see a dozen Indian women resplendent in their saris who, if you are male and look at them, will offer you a price and then follow you closely for a few paces to make certain that you truly aren’t interested in their sexual services. After passing the 7-Eleven, you may, if you are male, be accosted at the corner of Nathan Road by other young women, from Mongolia, Malaysia, Indonesia, and elsewhere. You will also be accosted by a number of South Asian men offering to make you a suit—“A special deal just for you.” They may be joined by copy-watch sellers, offering various brands of watches for a small fraction of the price of the original. If you hesitate and show interest, they will lead you to any of the numerous shadowy emporiums in nearby buildings.

Once you cross Mody Road and are on the same block as Chungking Mansions (whose entrance is now some one hundred feet away), the restaurant touts may be in wait if it is the right time of day, shilling for a half dozen different Chungking Mansions curry places. You must either ignore them or decide to follow one tout to his restaurant; otherwise you will be mobbed. You may also—especially if you are white—find a young man quietly sidling up to you and whispering, “Hashish?” and if you query further, numerous other substances as well. Once you reach the steps at the entrance to Chungking Mansions, the guesthouse touts will set upon you if it is late afternoon or evening, with a South Asian man saying, “I can give you a nice room for HK$150” (US$19),*1 and a Chinese man saying, just out of earshot of the South Asian, “Those Indian places are filthy! Come to my place! It’s clean”—possibly so, but at a considerably higher price.

After you have passed through this gauntlet of attention, you will find yourself in the midst of Chungking Mansions’ swirl, at times more people crowded in one place than you have seen in your entire life. It is an extraordinary array of people: Africans in bright robes or hip-hop fashions or ill-fitting suits; pious Pakistani men wearing skullcaps; Indonesian women with jilbab, Islamic head coverings; old white men with beer bellies in Bermuda shorts; hippies looking like refugees from an earlier era; Nigerians arguing confidently and very loudly; young Indians joking and teasing with their arms around one another; and mainland Chinese looking self-contained or stunned. You are likely to find South Asians carting three or four huge boxes on their trolleys with “Lagos” or “Nairobi” scrawled on the boxes’ sides, Africans leaving the building with overstuffed suitcases packed with mobile phones, and shopkeepers selling everything on earth, from samosas to phone cards to haircuts to whiskey to real estate to electrical plugs to dildos to shoes. You will also see a long line of people of every different skin color waiting at the elevator, bound for a hundred different guesthouses.

You may wonder, upon seeing all of this, “What on earth is going on here? What has brought all these different people to Chungking Mansions? How do they live? Why does this place exist?” These are the questions that led me to begin my research in Chungking Mansions. I first came to Chungking Mansions in 1983 as a tourist, staying for a few nights before moving on. I came to Hong Kong to live in 1994, visiting Chungking Mansions every couple of months to eat curry and to take in the world there. In 2006, I began formally to do anthropological research in Chungking Mansions, finding out all I could about the place and the people in it and seeking to understand Chungking Mansions’ role in globalization. I have been living in Chungking Mansions for one or more nights each week over the past three and a half years and have spent my every available moment there (it is a thirty-minute train ride from the university where I live), seeking to answer the questions posed above and, more than that, to understand Chungking Mansions’ significance in the world.

Over the past few years I have found some answers. Let me describe a typical walk of late from the train station exit to Chungking Mansions. The Indian sex workers are already out this early evening but know that I’m not a customer, so they ignore me, except for the new ones who see in a white face the chance to make a lot of money; their seniors tell them not to bother. A copy-watch salesman friend waves hello from behind his dark glasses. He was partially blinded by the police in his South Asian country, he has told me, when they taped open his eyelids and forced him to gaze at the sun all day. But the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the arbiter of his case and his fate, may not believe him, he worries, because he cannot provide proof. So he illegally works, attempting to save up enough money to eventually be able to receive cornea transplants. Meanwhile, he looks out for undercover police as best he can and accosts every likely customer: “White people are the best. They buy more than anyone else.” But sales are bad this month, and he can hardly pay his rent, let alone save for his longed-for transplants. Whether he was blinded by the police in his country, or by a congenital problem or an accident of some sort, is an open question—how much of his account is true is not for me to judge. But it’s good to come across him again.

A few steps later, a restaurant tout greets me effusively. I haven’t seen him for two months because he’s been back in Kolkata, his home—he is illegally working in Hong Kong as a tourist. He proudly shows me a picture of his baby son, born last month, but says that he’s happy to be back in Hong Kong. “I have to support my family! . . . I miss my family, but the pay’s much better here in Hong Kong, so . . . ” But he spends a significant portion of his money calling home on his mobile phone, he tells me ruefully.

At the entrance to Chungking Mansions, I meet a Nigerian trader I haven’t seen for six months. He says that he couldn’t return to Hong Kong because the exchange rates back home were exorbitant, and he couldn’t get the dollars he needed. “Now I finally can come back. I had an order for 4,000 phones, but I couldn’t come here to pick them up. Now I can do that. I can make money again.” He flies back home the day after tomorrow, after checking every phone as closely as he can. His friend, whom I meet for the first time, is going into south China the day after tomorrow—“It’s better to buy clothes there than in Hong Kong now. I can get 30,000 shirts made following my own style”—after picking up his visa. Both are worried that exchange rate fluctuations might kill any chance of making a profit, not to mention the vicissitudes of customs back home and the dangers of getting cheated in China and in Chungking Mansions. “It’s so hard to make any money,” they say, the continuing refrain of so many traders I have spoken with.

A few steps later, I meet an Indian friend standing near the guard post, He works for a large Hong Kong corporation by day and by night comes back to help his family at their guesthouse. His agony at present is not simply that he has no time, but more that he has a Hong Kong Chinese girlfriend that his parents refuse to recognize. He wonders what he should do—choose his girlfriend or his parents—but at present, he just can’t decide and only waits.

I then meet a West African friend who until recently ran a business in south China. He, unlike almost every other African trader I’ve met, has had the capital to obtain a Hong Kong ID card in return for a US$200,000 investment, which he has made by renting and outfitting an electronics store in Chungking Mansions, one that his fellow Africans and fellow Muslims will patronize, he hopes. His wife and children have recently come to Hong Kong, and he looks forward to making a new life for them here, as against what he feels to be the lawlessness of China. “You can trust Hong Kong.” Of course, whether he can make money remains to be seen, especially in the economic downturn that has affected Chungking Mansions as much as anywhere else in the world; but he believes that by being an honest Muslim merchant, he can succeed in the building.

Another few steps later, I meet a young South Asian whom I’ve only met once before. He tells me that he has lost his job and is desperate. “What am I going to do? I have no money! Everyone in my family depends on me!” I don’t know if he is telling the whole truth, but he certainly seems frantic. I don’t know him, so I only give him HK$100 and wish him luck. I hate playing God this way, but what can I do? There are so many like him. The next time I come back to Chungking Mansions, I don’t see him; in fact, I have never seen him again.

These people are all denizens of Chungking Mansions, the subject of this book. In the book’s first chapter, I explore Chungking Mansions as a place: its reasons for existing, its significance, and its architecture, history, and organization. In its second chapter, I depict the different groups of people in Chungking Mansions, from African traders to Chinese owners to South Asian shopkeepers to asylum seekers, sex workers, heroin addicts, and tourists, and my interviews and travels around the globe with various of these people. In its third chapter, I describe the goods that pass through the building and the shopkeepers and traders who buy and sell these goods in their global passages. In its fourth chapter, I examine the web of laws that constrain all in the building and particularly consider asylum seekers, with their lives placed in limbo. Finally, in its fifth chapter, I explore the building’s significance, for those within it and for the world as a whole, and speculate as to its future.

This book is about Chungking Mansions and the people within it, but it is also about “low-end globalization,” a form of globalization for which Chungking Mansions is a central node, linking to an array of nodes around the world, from Bangkok to Dubai to Kolkata, Kathmandu, Kampala, Lagos, and Nairobi. Low-end globalization is very different from what most readers may associate with the term globalization—it is not the activities of Coca-Cola, Nokia, Sony, McDonald’s, and other huge corporations, with their high-rise offices, batteries of lawyers, and vast advertising budgets. Instead, it is traders carrying their goods by suitcase, container, or truck across continents and borders with minimal interference from legalities and copyrights, a world run by cash. It is also individuals seeking a better life by fleeing their home countries for opportunities elsewhere, whether as temporary workers, asylum seekers, or sex workers. This is the dominant form of globalization experienced in much of the developing world today.

Chungking Mansions flourishes in a small space through which enormous amounts of energy, people, and goods flow, but this is nonetheless tiny in volume compared to the scale of the developed-world economy that surrounds it. It is one dilapidated building compared to all the financiers’ skyscrapers in Tsim Sha Tsui and especially across Hong Kong harbor in the Central District, Hong Kong’s concentrated wealth as a center of high-end globalization ten minutes away by train and a universe distant. This book is about Chungking Mansions, but it is also about all the world, in its linkages, its inequalities, and its wonders.

“Ghetto at the Center of the World”

Chungking Mansions is a place that is terrifying to many in Hong Kong. Here are some typical comments from Chinese-language blogs and chat rooms: “I feel very nervous every time I walk past [Chungking Mansions]. . . . I feel that I could get lost in the building and kidnapped.” 2 “I am . . . afraid to go [to Chungking Mansions]. There seem to be many perverts and bad elements there.”3 “I saw a group of black people and Indian people standing in front of a building. I looked up and saw the sign ‘Chungking Mansions.’ Just as the legend goes, it is a sea of pitch darkness there.”4 “I went with some classmates for curry today. It was my very first time going to Chungking Mansions. I felt like I was in another country. The curry was all right, but I was scared when I entered the building . . . because my dad told me I should never go in.”5 As this last quotation indicates, some Hong Kong Chinese, particularly young people, are attracted to Chungking Mansions because of its half dozen semifashionable curry restaurants on its higher floors, but many more are afraid to even enter the building.

This fear of Chungking Mansions extends beyond Hong Kong—it is apparent among commentators from the developed world as a whole. Consider the following passages, largely written by American and European journalists, also taken from the Internet:

Chungking Mansions is the sum of all fears for parents whose children go backpacking around Asia. . . . In the heart of one of the world’s richest and glitziest cities, its draw card of cheap accommodation has long been matched by the availability of every kind of vice and dodgy deal, not to mention its almost palpable fire and health risks.6

Chungking Mansion is the only place I have ever been where it is possible to buy a sexual aid, a bootleg Jay Chou CD and a new, leather-bound Koran, all from the same bespectacled Kashmiri proprietor who can make change for your purchase in any of five currencies. It is also possible, while wandering the alleys, hallways and listing stairwells of Chungking Mansions, to buy a discount ticket to Bombay, purchase 2,000 knock-off Tag Heuer watches or pick up a counterfeit phone card that will allow unlimited calls to Lagos, Nigeria. . . . You can disappear here. Thousands have. Most of them by design.7

Chungking Mansions offers very cheap accommodation for backpackers and is a hideout for illegals such as those who have overstayed their visas. It is a den of crime, of drug trafficking, prostitution and generally all the nastiness that goes on in the world you can find in Chungking Mansions. . . . Personally I go there for the curry.8

This dodgy reputation dates from the 1970s, when Chungking Mansions emerged as a hangout for Western hippies and backpackers. It grew during the 1980s and early 1990s, as confirmed in the dark portrayal in Wong Karwai’s famous 1994 film Chungking Express, a film about Hong Kong Chinese postmodern romance that takes place, in part, in Chungking Mansions. The film depicted Chungking Mansions misleadingly. Hong Kong Chinese did not usually come to Chungking Mansions in the early 1990s, and those who did stuck out so obviously that they probably couldn’t have engaged in the kinds of activities the film depicts. Nonetheless, the film does accurately convey the seedy atmosphere of the place at that time. This dodgy reputation of Chungking Mansions continues today, largely because of the massive presence of South Asians and Africans in the building, as seen through the quasi-racist lenses of Hong Kong Chinese and other rich-world peoples who don’t quite know how to interact with their poor-world brethren.

The biggest reason why so many people in Hong Kong and in the developed world are terrified of Chungking Mansions is simply that they are afraid of the developing world and the masses of poor people who come to the developed world for some of the crumbs of its ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prelude: A Note on Hong Kong

- 1. Place

- 2. People

- 3. Goods

- 4. Laws

- 5. Future

- Notes

- References

- Index