eBook - ePub

Mothers on the Move

Reproducing Belonging between Africa and Europe

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The massive scale and complexity of international migration today tends to obscure the nuanced ways migrant families seek a sense of belonging. In this book, Pamela Feldman-Savelsberg takes readers back and forth between Cameroon and Germany to explore how migrant mothers—through the careful and at times difficult management of relationships—juggle belonging in multiple places at once: their new country, their old country, and the diasporic community that bridges them.

Feldman-Savelsberg introduces readers to several Cameroonian mothers, each with her own unique history, concerns, and voice. Through scenes of their lives—at a hometown association's year-end party, a celebration for a new baby, a visit to the Foreigners' Office, and many others—as well as the stories they tell one another, Feldman-Savelsberg enlivens our thinking about migrants' lives and the networks and repertoires that they draw on to find stability and, ultimately, belonging. Placing women's individual voices within international social contexts, this book unveils new, intimate links between the geographical and the generational as they intersect in the dreams, frustrations, uncertainties, and resolve of strong women holding families together across continents.

Feldman-Savelsberg introduces readers to several Cameroonian mothers, each with her own unique history, concerns, and voice. Through scenes of their lives—at a hometown association's year-end party, a celebration for a new baby, a visit to the Foreigners' Office, and many others—as well as the stories they tell one another, Feldman-Savelsberg enlivens our thinking about migrants' lives and the networks and repertoires that they draw on to find stability and, ultimately, belonging. Placing women's individual voices within international social contexts, this book unveils new, intimate links between the geographical and the generational as they intersect in the dreams, frustrations, uncertainties, and resolve of strong women holding families together across continents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mothers on the Move by Pamela Feldman-Savelsberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226389882, 9780226389745eBook ISBN

97802263899121

Introduction

We are always on the move, for ourselves and for our children.

MAGNI, Berlin 2009

Toward the beginning of our multiyear friendship and year of intense collaboration regarding maternity, mobility, and belonging, my Cameroonian research assistant leaned her head toward mine, coffee from a Berlin university library café steaming up our glasses. A migrant mother herself, Magni1 confided, “We are always on the move, for ourselves and for our children.” Like many of my interlocutors, this young woman embodies the rushing movement of a working mother getting through her day, the bureaucratically regulated physical movement across international boundaries, and the upwardly mobile movement of an international student. Like many other Cameroonian women, Magni had migrated to Germany in search of better conditions in which to raise her family.

Ironically, Cameroonian women often find that their migration creates challenges to the social and emotional connections that constitute belonging—a complex mix of recognition by, and attachment to, a particular place or group. Like many others we spoke with, Magni found her relations, her things, and her loyalties stretched between Cameroon and Germany. In the course of our work together, Magni and I heard many stories regarding migrant women’s difficulties with respect to reproduction and belonging, summarized in their recurrent exclamation that “it’s hard being a mother here.” Their difficulties were emotional and social, medical and legal. Despite their complaints, clearly it was through their children that our Cameroonian interviewees managed to overcome the burdens of exclusion and forge new layers of belonging. Through their children, young women strengthened connections to kin in Cameroon and built new connections to Cameroonian diasporic communities and to German officials. Having and raising children in Berlin may have been hard and lonely for these recent immigrants, but it also helped young mothers adjust to a new place.

This book explores how Cameroonian women in Germany seek to establish their belonging through birthing and caring for children and what happens to their ties in places of origin and places of migration in the process. It is partly a tale about immigrant integration—belonging in Germany—but also a story about belonging in new ways with fellow migrants in Berlin and with Cameroonians back home.

Cameroon is a small country with a land mass approximately the size of California, nestled between West and Central Africa. A century ago, Cameroon was still a German colony; split between French and British rule following World War One, Cameroon gained political independence in 1960. As more and more of its approximately 22 million inhabitants (World Bank 2013) are seeking education, jobs, and new lives in Europe, Cameroonian migration to Berlin represents one variation of a larger phenomenon of African migration to the global north.

Africans are migrating to Europe more than ever before, migrating as families, to sustain families, and to found new families. In a world of movement, what does it mean to belong? How do migrant mothers create a sense of belonging for themselves, for their children, and through their children? A decade after the turn to the new millennium, this tension among mobility, rootedness, and reproduction was palpable in my interactions with Cameroonian mothers in Berlin. Each woman narrated different hardships about motherhood “on the move,” simultaneously revealing how those hardships prompted them to extend and intensify their social networks while occasionally putting other connections on hold. From the tender phase of mother-infant care through the turbulent teen years, mothers deploy their children to forge connections across a variety of social networks.

Belonging to these social networks—kin groups and households, ethnic or migrant community associations, and states—encompasses a range of statuses and feelings. Through their children, women may maintain or gain their citizenship status, national or ethnic identity, emotional connection, and feelings of recognition, acceptance, and comfort. Women’s and their children’s belonging can be felt (an interior state), performed (by behaving according to certain codes), or imposed (e.g., when a bureaucrat categorizes a woman as deserving of assistance). In interaction with family members stretching from Cameroon to Germany, with migrant associations, and with German officials, migrant mothers variably enact belonging through rights, duties, and expectations regarding financial transactions (remittances, fees, taxes); decision making (voting, advice); physical presence (residence and visits); bodily care (of mothers and infants); and use of symbols, including language choice and naming practices).

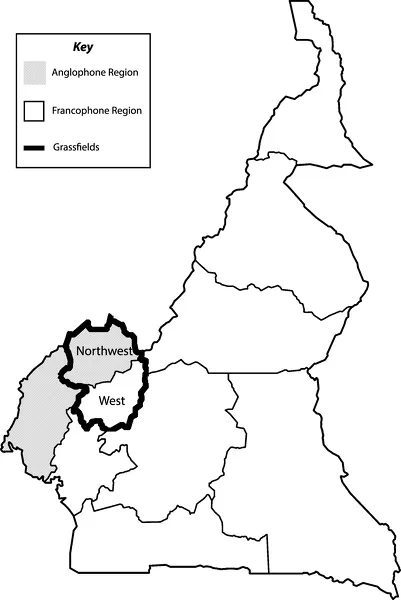

Migration complicates belonging, stretching some connections to the breaking point while facilitating new ones. This is particularly so in the highland Grassfields area, spanning two Cameroonian provinces and bearing a long history of labor migration and political opposition to the central state within Cameroon. Spanning two Cameroonian provinces, Grassfields peoples include the French-speaking Bamiléké of the West Region and their ethnic cousins from the English-speaking Northwest Region (see figure 1.1). Bamiléké make up 30 percent and Anglophones 20 percent of Cameroon’s population of 22 million. A series of economic and political crises in Cameroon since the 1980s sharpened and politicized ethnic boundaries, a phenomenon that scholars term the “politics of belonging” (e.g., Geschiere 2009).

FIGURE 1.1. Map of Cameroon.

Cameroonians from this area—the focus of my research—migrate to improve the conditions in which they regenerate families. In the Cameroonian cities where Bamiléké and Anglophones move, locals consider them ethnic strangers; discrimination and corruption (Transparency International 2014) make accessing health care and supporting a family difficult. Hard labor, poor nutrition, and disease render women’s fertility fragile. Indeed, the statements I heard in Berlin about the difficulties of motherhood in the diaspora reminded me of previous encounters with mothers in both rural and urban Cameroon, a recurrent gesture of hands clapped together then opened, palms up, indicating, “We have nothing”—not enough children, not enough food or material goods or the conditions to grow healthy families.

These conditions of reproductive insecurity in Cameroon motivate many to search for well-being through transnational migration (see also Stoller 2014). Cameroonians call migration to seek one’s fortune abroad “bushfalling.” In this case, “bush” denotes an unknown place simultaneously full of rich potential and mysterious danger. To “fall bush” literally means to hunt or to cultivate distant fields, but in contemporary Cameroon it refers to migration to Europe, North America, and occasionally the Middle East and Asia (Alpes 2011; Fleischer 2012; Nyamnjoh 2011; Pelican and Tatah 2009; Pelican 2013).The predicaments that Bamiléké and Anglophone women face in Cameroon motivate bushfalling and tell us why young Cameroonian mothers find themselves in Berlin.

Although transnational migration is one way Cameroonian women seek to overcome Cameroonian impediments to growing and supporting their families, transnational migration renders women’s reproduction and belonging even more insecure. Through migrating, African women make “choices for their future children and for their children’s future” (Shandy 2008, 822), based on legal, economic, cultural, and emotional logics. These choices entail sacrifice as mothers leave the embrace of their families and familiar ways of being behind to face the material, social, and emotional challenges of starting anew in a strange place. While moving across space is one way to be socially mobile and realize middle-class aspirations, migration necessitates managing new sets of expectations about belonging-through-children that emanate from kin back home as well as from laws and bureaucratic procedures in Germany.

Women seek to manage these often contradictory expectations by forging connections that support them as mothers and allow them to care for others. Finding partners, being pregnant, giving birth, and rearing children—in other words, practices of physical and social reproduction—tie mothers to families, to communities, and to states. For example, when parents care for their children, they fulfill family expectations while drawing upon help from extended kin or entitlements from community associations and government social service agencies. Such exchanges embed mothers in overlapping fields of social relationships and thus form the basis of their multilayered belongings.2 Mothers purposefully build, maintain, and manage networks through their reproductive practices. And mothers shape their reproductive decisions in part because they are striving for the sense of positive value and recognition that comes with belonging.

Mothers negotiate belonging through exchanges of care, money, goods, and words within these networks. Later in this chapter, I will imagine these ties as electrical circuits along which exchanges flow in discontinuous ways that respond simultaneously to external constraints and to the emotions of mothers’ network of relationships. I draw inspiration from Jennifer Cole and Christian Groes’s recent conceptualization of affective circuits in their work on personhood and the pursuit of regeneration in African migration to Europe (2016). In this book, we will see that mothers juggle multiple, sometimes contradictory, expectations by making, dropping, and picking up again ties established through kinship, community organizations, and state actors. By situationally cultivating certain affective circuits and letting other circuits temporarily “rest,” Cameroonian migrant mothers manage the contingent nature of belonging for mothers who are “always on the move.”

Examining motherhood and child-rearing among Cameroonians in Berlin invites us into a larger world of African migrations and transnational family-making. Much of the literature on transnational families examines how women create and manage connections to others through the circulation of children, including fostering, adoption, and other forms of distributed parenting (e.g., Alber, Martin and Notermans 2013; Coe 2013; Leinaweaver 2008, 2013; Parreñas 2005; Reynolds 2006). But it neglects the role childbearing plays in mothers’ webs of belonging. And what happens when mothers and children move together, or when children born in the country of migration stay with their immigrant mothers?

This book focuses on childbearing and child-rearing as processes of belonging and not-belonging for Cameroonian migrant mothers in Berlin. By soliciting care from multiple directions, the young child helps its mother with her transition to a new place. Sending older children to school and commiserating with other mothers about the challenges of raising tweens provides migrant mothers further opportunities to reflect upon what it means to be African while becoming established in Europe. Furthermore, by sharing experiences about their encounters with the state apparatus and bureaucracy in Berlin, mothers develop a migrant legal consciousness, common orientations about getting along in a new land. Women resolve, manage, and reproduce the challenges of migration through their efforts to forge networks with kin, with community organizations, and with authorities. Along these affective circuits, migrant mothers circulate emotions, support, and ideas that orient them to a new cultural, reproductive, and juridical landscape. Although Cameroonian mothers repeatedly lament that “It’s hard being a mother here,” they recognize that their children create opportunities as well as difficulties for their new lives in Germany.

Concepts

Four concepts frame my argument: reproductive insecurity, belonging, affective circuits (i.e., emotion-laden social networks), and legal consciousness. I take reproductive insecurity as a motivator to movement, including young Cameroonians’ drive toward both physical and social mobility. Mobility complicates belonging, which encompasses both jural-political and affective aspects. Jural incorporation and emotional belonging condition forms of relatedness and the exchanges that flow along and form affective circuits within Cameroonian women’s social networks. Stories about belonging and exclusion, about encounters with neighbors, teachers, physicians, and public officials, circulate along these same social ties, sedimenting into forms of legal consciousness and political subjectivity. Affective circuits and legal consciousness are the tools through which mothers on the move navigate the tricky seas of reproduction and belonging.

REPRODUCTIVE INSECURITY

Connections between reproduction and belonging are sharply revealed by instances in which reproduction goes awry. I propose the term “reproductive insecurity” to address the conditions and anxieties surrounding such reproductive challenges. Reproductive insecurity encompasses social and cultural reproduction (e.g., the reproduction of social inequalities among culturally defined groups) as well as biological reproduction (creating people to populate those groups). While my Berlin interlocutors tell me that “all reproduction in the diaspora is a challenge,” some examples from my work among the Bamiléké in Cameroon illustrate instances when biological and social reproduction become short-circuited in communities of origin (what migration researchers call “sending communities”). A woman may face infertility (Feldman-Savelsberg 1999) or repeated miscarriages (Feldman-Savelsberg, Ndonko and Yang 2006), putting her marriage and community belonging at risk. By seeking an abortion, she may break one set of cultural proscriptions to maintain culturally appropriate models of motherhood (Feldman-Savelsberg and Schuster n.d.). Her reproduction may become part of ethnic stereotyping in the context of autochthony movements that seek to exclude Bamiléké migrants from full Cameroonian citizenship (Feldman-Savelsberg and Ndonko 2010; Geschiere 2007). These and other challenges to reproduction and belonging occur frequently in the medically and politically treacherous context of sub-Saharan Africa.

These Cameroonian examples reveal the important interrelations among biological reproduction, cultural notions of procreation, and social reproduction. Human biological reproduction occurs in the context of social institutions that shape patterns of sexual partnerships and the physical health necessary for conception, gestation, and childbirth. Just as important for reproductive insecurity are the ways participants understand these processes, where children come from and how they are made (Delaney 1991). To illustrate, let’s visit the Bamiléké paramount chieftaincy (called “fondom” in Cameroonian Pidgin English and in English-language scholarship on Cameroon) where I began my long research encounter with Cameroon. During the 1980s in Bangangté, parents understood procreation through rich culinary metaphors of hot sex, gendered ingredients, and cooking-pot wombs. Thirty years later their children, now cosmopolitan migrant mothers in Berlin, framed procreation in biomedical terms but retained their mothers’ concerns regarding the effects of social discord on fertility. Cameroonian ideas about procreation, while changing over time, clearly place biological reproduction within the realm of social relationships.

The circumstances of birth create multiple layers of social relationships, as a child is born into a lineage, strengthens its parents’ conjugal and affinal ties, and gains citizenship either on the basis of genealogy (jus sanguinis) or place of birth (jus soli). Sustaining these relationships and their associated values, norms, and potential inequalities over time constitutes social reproduction (Bourdieu 1977; Edholm, Harris and Young 1978). As Colen points out in her work on “stratified reproduction” (1995), both biological and social reproductive labors are processes distributed among multiple actors—mothers, fathers, siblings, aunts, grandmothers, and non-kin caregivers (cf. Laslett and Brenner 1989; Goody 2008; Coe 2013). Distributed reproductive labors forge a number of relationships that can be rendered insecure—through colonial and postcolonial intrusions, through structured misunderstandings between reproductive health providers and immigrant clients (Sargent 2011), and through the “exclusionary incorporation” (Partridge 2012) that greets African migrants on European shores.

We can see that numerous material, cultural, and social conditions render human reproduction, cultural belonging, and social reproduction problematic. Reproductive insecurity encompasses the conditions and social experience of these difficulties and linkages (Feldman-Savelsberg, Ndonko, and Yang 2005). The conditions rendering biological and social reproduction insecure (e.g., social determinants of health inequalities such as poverty, infectious disease, social disruption, violence) are primarily political and economic, often linked to domestic and transnational labor migration. These conditions generate personal and collective anxiety, the affective aspect of reproductive insecurity. The emotional force of reproductive insecurity is revealed and (re)produced through speech and bodily practices expressing fear of reproductive mishaps from infertility and pregnancy loss to “demographic theft” (Castañeda 2008) as well as through concerns about the ability to maintain—or reproduce—a particular form of social organization and sense of cultural distinctiveness.3

BELONGING

Belonging is one way of expressing relatedness, key to anthropology from its earliest studies of kinship to more recent work on reproduction and migration (e.g., Leinaweaver 2008, 2011). Nothing could be more central to anthropology than the constitution and continuity of culturally defined groups and ways in which group membership is established and experienced for individuals. Despite the de facto permeability of their boundaries, these groups—based on such attributes as kinship, residence, gender, ethnicity, religion, or citizenship—are the building blocks of social organization. The process of creating and maintaining group membership—belonging—for oneself and for one’s dependents is an important part of reproductive labor. Indeed, social reproduction is not only about reproducing structured relationships among individuals and groups; it is also about reproducing emotional commitment—an emotional sense of belonging—to those groups and positions.

Belonging is an expansive term, encompassing relatedness based on (1) social location, (2) emotional attachment through self-identifications, and (3) institutional, legal, and regulatory definitions that simultaneously grant recognition to and maintain boundaries between socially defined places and groups (Y...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Cast of Characters

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Cameroonian Predicaments

- 3 Starting Cameroonian Families in Berlin

- 4 Raising Cameroonian Families in Berlin

- 5 Civic Engagement

- 6 In the Shadow of the State

- Notes

- References Cited

- Index