- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In our architectural pursuits, we often seem to be in search of something newer, grander, or more efficient—and this phenomenon is not novel. In the spring of 1910 hundreds of workers labored day and night to demolish the Gillender Building in New York, once the loftiest office tower in the world, in order to make way for a taller skyscraper. The New York Times puzzled over those who would sacrifice the thirteen-year-old structure, "as ruthlessly as though it were some ancient shack." In New York alone, the Gillender joined the original Grand Central Terminal, the Plaza Hotel, the Western Union Building, and the Tower Building on the list of just one generation's razed metropolitan monuments.

In the innovative and wide-ranging Obsolescence, Daniel M. Abramson investigates this notion of architectural expendability and the logic by which buildings lose their value and utility. The idea that the new necessarily outperforms and makes superfluous the old, Abramson argues, helps people come to terms with modernity and capitalism's fast-paced change. Obsolescence, then, gives an unsettling experience purpose and meaning.

Belief in obsolescence, as Abramson shows, also profoundly affects architectural design. In the 1960s, many architects worldwide accepted the inevitability of obsolescence, experimenting with flexible, modular designs, from open-plan schools, offices, labs, and museums to vast megastructural frames and indeterminate building complexes. Some architects went so far as to embrace obsolescence's liberating promise to cast aside convention and habit, envisioning expendable short-life buildings that embodied human choice and freedom. Others, we learn, were horrified by the implications of this ephemerality and waste, and their resistance eventually set the stage for our turn to sustainability—the conservation rather than disposal of resources. Abramson's fascinating tour of our idea of obsolescence culminates in an assessment of recent manifestations of sustainability, from adaptive reuse and historic preservation to postmodernism and green design, which all struggle to comprehend and manage the changes that challenge us on all sides.

In the innovative and wide-ranging Obsolescence, Daniel M. Abramson investigates this notion of architectural expendability and the logic by which buildings lose their value and utility. The idea that the new necessarily outperforms and makes superfluous the old, Abramson argues, helps people come to terms with modernity and capitalism's fast-paced change. Obsolescence, then, gives an unsettling experience purpose and meaning.

Belief in obsolescence, as Abramson shows, also profoundly affects architectural design. In the 1960s, many architects worldwide accepted the inevitability of obsolescence, experimenting with flexible, modular designs, from open-plan schools, offices, labs, and museums to vast megastructural frames and indeterminate building complexes. Some architects went so far as to embrace obsolescence's liberating promise to cast aside convention and habit, envisioning expendable short-life buildings that embodied human choice and freedom. Others, we learn, were horrified by the implications of this ephemerality and waste, and their resistance eventually set the stage for our turn to sustainability—the conservation rather than disposal of resources. Abramson's fascinating tour of our idea of obsolescence culminates in an assessment of recent manifestations of sustainability, from adaptive reuse and historic preservation to postmodernism and green design, which all struggle to comprehend and manage the changes that challenge us on all sides.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Obsolescence by Daniel M. Abramson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226478050, 9780226313450eBook ISBN

97802263135971

Inventing Obsolescence

Before Obsolescence

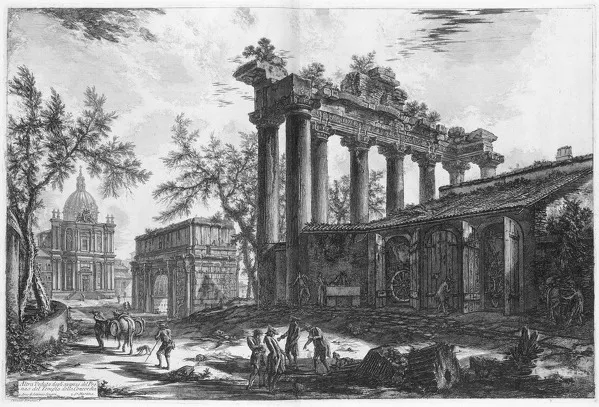

Prior to the twentieth century, conceptions of architectural time in the Western tradition prioritized permanence and gradual change. The past persists visibly in centuries-old monuments, such as the ancient Roman arch of Septimius Severus, illustrated by the famed eighteenth-century printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi (fig. 1.1). Nature and history worked their slow decay, the same picture shows. At the same time, human reuse adapted gently to the past, as we can see in the middleground, where the ruined Temple of Saturn is repurposed to mundane ends. And new architecture hewed to deep time as well. The seventeenth-century baroque church of Santi Luca e Martina, in Piranesi’s background, features classical columns and a symmetrical composition, which echo antecedents from centuries before. Ruinscapes like these parade architectural continuity. Time proceeds slowly. The past endures. Even when the nineteenth-century English architect John Soane famously had his monumental Bank of England building pictured in an exhibition watercolor as a ruin, with its roofs and walls sheared away, he did so not to promote the value of transience but to underscore his and the institution’s dream of immortal, Romanlike grandeur.1

FIGURE 1.1. Remains of the Temple of Concord, Rome, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, late eighteenth century. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Art Resource, NY.

Aesthetically, classical design, the dominant Western tradition since the Renaissance, strove for ideals of fixity and permanence. The Italian theorist and architect Leon Battista Alberti, in his seminal fifteenth-century treatise, defined formal perfection as “that reasoned harmony of all parts within a body, so that nothing may be added, taken away, or altered, but for the worse.”2 According to Alberti’s prescription, a building was beautiful only when it appeared unchangeable and finished in time. Architects followed this vision for centuries. Constructions of permanent stone, like Santi Luca e Martina in Piranesi’s print, are embellished with centralizing motifs, like temple fronts or triumphal arches, and framed at their ends by projecting stonework or columns. These conventions of centralized, framed arrangement embodied an aesthetic of symmetry, hierarchy, and completion, implying an eternal order in their very composition.

Temporal continuity and stability was valued beyond the classical tradition. Mid-nineteenth-century British medieval revivalists esteemed historical “development”—“continued, gradual, tranquil” change, explains the architectural historian David Brownlee.3 The Gothic revival philosopher and critic John Ruskin extolled the virtues of permanence. “Architecture is always destroyed causelessly,” he proclaimed in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849).4 Other nineteenth-century observers, who accepted modernity more readily than Ruskin, still wished for traditional architectural endurance. “We are not like our fathers, building for a short time only,” the American critic Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer wrote in the Century Illustrated Magazine in 1884 about modern commercial New York. “Their structures have proved but temporary, while for ours a life may be predicted as long as the city’s own.”5 Van Rensselaer acknowledged the explosive initial development of a modern city but wished to see it slowed down in maturity, returning to architectural longevity.

To be sure, impermanent structures had always existed. Festivals, pageants, coronations, and fairs throughout history stood just for a moment. Famously in Japan, the wood temples at Ise have for centuries been reconstructed identically every two decades. But Japanese material impermanence fixes permanent principles; each generation internalizes the religious and architectural lessons of the past. The buildings may be deliberately transient, but the goal is eternal values. Occasionally, a building type in history had to face up to modern-style obsolescence—rapid, continuous devaluation and supersession engendered by external factors of innovation and competition. Renaissance fortifications, for instance, had notably short lives owing to improved siege technology. But this was unusual. Durability was the norm in building and values. It was only in the twentieth century that obsolescence became understood as a universal condition of built environment change—permanent and ceaseless replacement of structures and habits, applicable to all building types, regardless of function, form, and cultural meaning.

Another historical antecedent of modern obsolescence might perhaps be found in past large-scale urban renewals caused by natural disaster, war, or politics. The famous mid-nineteenth-century redevelopment of Paris, led by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, impelled the poet Charles Baudelaire at the time to lament, “Alas, a city’s face changes faster than the heart of a mortal.”6 But no one at the time envisioned Haussmann’s redevelopment to be endless, rebuilt again and again, ad infinitum. Only in the twentieth century did a pace of unending, ceaseless change in the built environment come to be understood as the new normal.

In nineteenth-century culture the possibility of permanently shortened building lives and cultural values was recognized but not yet accepted as a desired end. Nathaniel Hawthorne in The House of the Seven Gables (1851) has the youthful “wild reformer” Holgrave declare provocatively, “It were better that [our public edifices] should crumble to ruin, once in twenty years, or thereabouts, as a hint to the people to examine into and reform the institutions which they symbolize.”7 Fixed building lives would reflect and impel radical change in each generation, Holgrave prophesies. By novel’s end, however, Holgrave has reversed himself. He admits that “the happy man inevitably confines himself within ancient limits.” And he imagines that he himself would “build a house for another generation” (emphasis added), not a short-life building.8

The romantic ideal—invented in the nineteenth century and ultimately disavowed by Holgrave—that each age produces its own architecture was influentially voiced in France by Victor Hugo. “This Will Kill That,” reads a famous chapter title in Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), one technology superseding another. He hypothesized that the printed page had replaced architecture in the fifteenth century as “the principal register of mankind.”9 In Hugo’s time, some contemporary structures did appear to satisfy the desire to express architecturally the industrial character of the age. But spectacles like the vast 1851 Crystal Palace glass-and-iron exhibition pavilion in London were not considered proper architecture precisely because of their evident impermanence, even as they housed and embodied the latest marvels of machine civilization. Other aspects of the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution did indirectly inspire the idea of architectural obsolescence and can be credited more directly with increasing the pace and scope of creative destruction generally.

The quickening business world, especially the cutting-edge railroad industry, which involved ever more people, goods, information, equipment, and capital, took an increasingly “deep and vested interest in a rigorous definition and measurement of time,” explains the geographer David Harvey.10 From this arose a new class of professional experts, including engineers, economists, and accountants, who sought to master not just space and nature, but that key factor in industrial productivity and profit management, time itself. Time’s effect on value was of particular concern to modern accounting. By 1840, historians report, “the concept of depreciation was widely known and the need to recognize wear and tear explicitly discussed in publications available to British and U.S. textile mill owners and managers.”11 Assessing financial losses due to material wear and tear allowed industrial enterprises to value more accurately their capital assets for taxation, financing, and sale purposes, taking into consideration the dimension of time. Depreciation thus represented “a rational tool for management facing diversity and complexity.”12

Obsolescence emerged alongside depreciation as a financial risk management tool. Yet whereas depreciation resulted from slow, more or less predictable, physical wear and tear, obsolescence was different. It “was the loss which is constantly arising from the superseding of machines before they are worn out, by others of a new and better construction,” said Karl Marx, citing an 1862 English source.13 He called this process “moral depreciation,” but the more common term was obsolescence, from the Latin obsolescere (to grow old). The term was used first in sixteenth-century England to describe human speech “growne out of use,” then in the nineteenth century to describe an organism’s loss of function, before also encompassing inanimate machinery’s loss of utility. In this newly understood process an object’s material integrity holds fast—it is still young and operates as intended—but its functional worth has declined. Something better has come along to devalue and supersede it, to make it expendable and disposable. By the early twentieth century the accounting distinction between depreciation and obsolescence was well established. “Depreciation in its narrow sense, is physical—obsolescence economic,” defined the real estate taxation expert Joseph Hall in 1925.14

In architecture, application of the idea of physical depreciation emerged in late nineteenth-century America as a product of insurance and builders’ estimates. The popular 1895 Architect’s and Builder’s Pocket-Book, by Frank E. Kidder, in its twelfth edition offered readers detailed life-span charts for a whole range of structures and materials, from frame to brick, dwelling to store, plaster to porches, with paint the shortest-lived component (five years) and sheathing the longest (fifty).15 The basis for these charts was an 1879 fire underwriter’s paper, which in turn was founded upon eighty-three builders’ reports from eleven western states. But economic obsolescence distinct from physical depreciation did not factor into Kidder’s life-span numbers, which were simply material wear-and-tear rates.

Before 1900 the notion of obsolescence was thus absent from architectural thought. Buildings were expected to last for generations, along with the values and habits they embodied. Structures might wear out, but that process was slow, regular, and remediable. Rapid urban change might occur at one moment, but redevelopment would not be ceaseless. No one imagined a state of permanent expendability in the built environment. That idea had yet to be invented.

New York and Reginald Bolton’s Theory

The concept of obsolescence, in the English language, was first applied to the built environment around 1910. Lower Manhattan was the early epicenter for the invention of the idea of architectural obsolescence. In the 1890s New York property corporations began investing tens of millions of dollars in large new structures to accommodate the growing numbers of lawyers, accountants, bankers, managers, and other white-collar workers servicing the new corporate American economy. These tenants drove demand for the latest plumbing, heating, and elevator technologies. Their ever-changing desires had the effect of devaluing even the most recently constructed accommodations. The scope of the demand required new kinds of institutions and organizations to finance construction. Previously real estate investment dollars had been gathered from individuals or small groups. But big buildings needed big money. New joint-stock real estate investment companies collected capital through stock issues from scores of individual investors and came to combine under one roof construction, finance, and real estate, such as that of the United States Realty and Construction Company. Moreover, these novel development entities used the existing money markets to innovate mortgage bonds, in effect cutting mortgages up into hundred- or thousand-dollar increments to be publicly sold to even more investors, making it possible to raise for building amounts of money heretofore unimaginable. As the professional building manager Earle Shultz wrote of later, similar Chicago developments, “Replacement of old, obsolete buildings was made possible by the flood of money provided by the bond houses.”16

The result of all this cash and credit flowing into commercial real estate was intense market volatility. Growth and speculation hastened demolition and new construction. A boom-and-bust environment developed, with demand rising even as oversupply threatened investment values. The risk of catastrophic loss was profound, and as a result real estate capitalists faced harrowing unpredictability. This was the context then for the unsettling demolition of the thirteen-year-old Gillender Building in 1910 and the disappearance of numerous other short-lived commercial structures across the United States. As the author Henry James wrote in 1907, shocked upon seeing New York after years away, “One story is good only till another is to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Inventing Obsolescence

- 2 Urban Obsolescence

- 3 The Promise of Obsolescence

- 4 Fixing Obsolescence

- 5 Reversing Obsolescence

- 6 Sustainability and Beyond

- Notes

- Illustration Credits

- Index