- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this jarring look at contemporary warfare and political visuality, renowned anthropologist of violence Allen Feldman provocatively argues that contemporary sovereign power mobilizes asymmetric, clandestine, and ultimately unending war as a will to truth. Whether responding to the fantasy of weapons of mass destruction or an existential threat to civilization, Western political sovereignty seeks to align justice, humanitarian right, and democracy with technocratic violence and visual dominance. Connecting Guantánamo tribunals to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, American counterfeit killings in Afghanistan to the Baader-Meinhof paintings of Gerhard Richter, and the video erasure of Rodney King to lynching photography and political animality, among other scenes of terror, Feldman contests sovereignty's claims to transcendental right —whether humanitarian, neoliberal, or democratic—by showing how dogmatic truth is crafted and terror indemnified by the prosecutorial media and materiality of war.

Excavating a scenography of trials—formal or covert, orchestrated or improvised, criminalizing or criminal—Feldman shows how the will to truth disappears into the very violence it interrogates. He maps the sensory inscriptions and erasures of war, highlighting war as a media that severs factuality from actuality to render violence just. He proposes that war promotes an anesthesiology that interdicts the witness of a sensory and affective commons that has the capacity to speak truth to war. Feldman uses layered deconstructive description to decelerate the ballistical tempo of war to salvage the embodied actualities and material histories that war reduces to the ashes of collateral damage, the automatism of drones, and the opacities of black sites. The result is a penetrating work that marries critical visual theory, political philosophy, anthropology, and media archeology into a trenchant dissection of emerging forms of sovereignty and state power that war now makes possible.

Excavating a scenography of trials—formal or covert, orchestrated or improvised, criminalizing or criminal—Feldman shows how the will to truth disappears into the very violence it interrogates. He maps the sensory inscriptions and erasures of war, highlighting war as a media that severs factuality from actuality to render violence just. He proposes that war promotes an anesthesiology that interdicts the witness of a sensory and affective commons that has the capacity to speak truth to war. Feldman uses layered deconstructive description to decelerate the ballistical tempo of war to salvage the embodied actualities and material histories that war reduces to the ashes of collateral damage, the automatism of drones, and the opacities of black sites. The result is a penetrating work that marries critical visual theory, political philosophy, anthropology, and media archeology into a trenchant dissection of emerging forms of sovereignty and state power that war now makes possible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Archives of the Insensible by Allen Feldman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Desisting Sovereignties

ONE

Before the Law at Guantánamo

The courts, to be sure, have law books at their disposal, but people are not allowed to see them, “It is characteristic of this legal system,” conjectures K., “that one is sentenced not only in innocence but also in ignorance.” Laws and definite norms remain unwritten in the prehistoric world. A man can transgress them without suspecting it and thus become subject to atonement. But no matter how hard it may hit the unsuspecting, the transgression in the sense of the law is not accidental but fated, a destiny which appears here in all its ambiguity. . . . In Kafka the written law is contained in books, but these are secret; by basing itself on them the prehistoric world exerts its rule all the more ruthlessly.

—Walter Benjamin, “Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death”

It may happen that a man wakes up one day and finds himself transformed into vermin. Exile—his exile—has gained control over him.

—Benjamin, “Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death”

The CSRT

On October 16, 2004, Ashraf Salim Abd Al Salam Sultan, a Libyan schoolteacher “captured” by the American military forces in Afghanistan, was subjected to a Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) held and staffed by U.S. military personnel at Guantánamo, where he had been imprisoned since 2002 after his rendition from Afghanistan.1 Salim was accused of being a member of a splinter faction of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (in opposition to the Gaddafi regime and reputedly allied to Al Qaida) and of being an enemy combatant against the American forces and its allies in Afghanistan at the time of his capture—abduction—in 2001.

The CSRT proceedings conducted reviews of 558 Guantánamo prisoners between 2004 and 2007 in which 361 detainees personally participated to contest their status as combatants against American forces and their allies in the hope of being released.2 The tribunals were based on classified information inaccessible to the prisoner (or erratically available in heavily redacted summaries); unclassified information that was inconsistently made available to the prisoners; and spoken testimony of the detainee given at his tribunal and in statements made prior to the hearing to “personal representatives” who were neither legal advocates nor chosen by the prisoner (legal representation was denied to the prisoners). Each hearing was staffed by a court reporter, a translator, and the personal representative and was adjudicated by a tribunal president and two associate tribunal members.

The prisoners were informed of the existence of inaccessible classified information and instructed on the role this archive would ultimately play in arriving at a final determination. Prisoners were explicitly or indirectly denied access to witnesses other than those already incarcerated at Guantánamo (see Salim’s transcript below). After face-to-face hearings with the prisoner, the tribunal members held in camera sessions without the prisoner, where the tribunal reviewed the classified information and arrived at a final adjudication. Transcripts of the sessions working with classified evidence are embargoed, unlike transcripts for the face-to-face hearing with the detainees, which were only involuntarily released well after the hearings through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit brought by the Associated Press. There was no burden of proof brought to bear on the classified information, evidence that was treated as presumptively valid and thus unchallengeable. Mark Denbeaux, the council to two detainees, a professor at Seton Hall University School of Law, and the principal investigator of a human-rights report on the CSRT, concluded that the government was attempting to replace habeas corpus with what he termed a “no hearing hearings” protocol that did not meet the requirements of due process.3

Almost from the start of his October 2004 hearing, Ashraf Salim questioned and contested the deployment of the classified information being used to adjudicate his case, information to which he had no access. This was not well received by the tribunal, who at the start of the hearing preemptively warned Salim against any emotional outbursts and disruptive behavior and threatened to remove him from the hearing.

TRIBUNAL PRESIDENT: You may be present at all open sessions of the Tribunal. However, if you become disorderly, you will be removed from the hearing and the Tribunal and the tribunal will con . . . [Detainee interrupts Tribunal president before she can continue her sentence] . . .

DETAINEE: How would I disturb order?

TRIBUNAL PRESIDENT: Becoming too emotional. Not listening to the Tribunal . . . if you become disorderly, you will be removed from the Tribunal and the Tribunal will continue to hear evidence in your absence.4

This warning from the tribunal was in part due to Salim’s “record” as an “uncooperative” prisoner in Guantánamo, which began before this hearing and continued long after, as the following report made subsequent to the hearing describes:

His overall behavior has been sporadically compliant and hostile to the guard force and staff. Detainee currently has 45 Reports of Disciplinary Infraction listed in DIMS with the most recent occurring on 1 April 2008, when he failed to follow guard instructions. He has two Reports of Disciplinary Infraction for assault with the most recent occurring on 29 March 2008, when he attempted to break a guard’s arm. Other incidents for which he has been disciplined include inciting and participating in mass disturbances, failure to follow guard instructions and camp rules, inappropriate use of bodily fluids, unauthorized communications, damage to government property, attempted assaults, provoking words and gestures, and possession of food and non-weapon type contraband. In 2007, he had a total of six Reports of Disciplinary Infraction and four so far in 2008.5

Salim’s reaction to his detention and imprisonment can be inferred from this record. In the hearings no testimony was taken concerning the conditions of imprisonment or the conditions under which prior interrogations of the prisoners had been conducted. Though his behavioral record was not directly raised to Salim in the face-to face tribunal encounter, one crucial and rhetoricized criterion of judgment was the abducted prisoner’s compliance or noncompliance with the regime of abduction prior to any definitive assignment of the prisoners’ combatant status. This was ultimately expressed in the CSRT finding that Salim was a “high threat from a detention perspective.”

The Guantánamo disciplinary apparatus was and is evidently engaged in manufacturing “security risks” through the technologies of incarceration. This unwritten protocol provides a crucial context for reading the CSRT process. The black site operates a culpabilizing system of managed “productive cooperation,” analogous to the techniques of immaterial labor, wherein detainees become active subjects in the coordination of the apparatus, which in this case is meant not to rehabilitate, but to manufacture terrorists through the protocols of detention.6 Standing outside positive law, the function of incarceration at the black site is to orchestrate ceremonies of criminalization, such as forced feeding and CSRT tribunals, sandwiched between the dead time of warehousing the human cogs of this certification machine. The production of a subject rendered adequate to the justifiability of capture through the conditions of incarceration explains why discussions of the release of Guantánamo inmates are short-circuited by the dogma of their “return to terror.” The inventive repertoire of misconduct ascribed to Salim by his captors, including his use of projectile body substances, expresses “autonomous productive synergies” as a display of virtuosity and affective labor functioning as “participative management as a technology of power, as technology for creating and controlling the subjective processes.”7 The post-Fordist prison produces the “entrepreneurial autonomy” of a prisoner as “terrorist” through confinement that promotes the detainees’ noncompliance with their detention as their compliance with the war on terror. In an ironic variation of the regimens of cognitive capitalism, the subject of penal production becomes the production of an incarceration-resistant subject.8 The manufacture of culpability and objective guilt at Guantánamo is immaterial insofar as it does not produce objects or tangible end products, but rather actions as ends in themselves.9

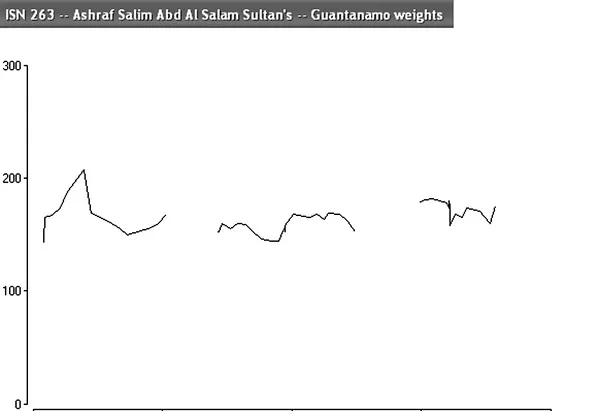

To manufacture self-willing, yet system-sustaining subjects is to fabricate structural guilt through the media of day-to-day disciplinary infractions, as well as more extreme protests such as hunger striking, resistance to forced feeding, and prisoner suicide. Forced feeding preempts the will to autonomy by prisoner hunger striking and suicide by severing the political will of the prisoner from the autonomic will of the body. The latter is circulated as an emblem of the regime’s penetrative power or subditio—the submergence of one will (the autonomic) into that of another (the penal regime). Forced feeding as subditio “ensure[s] that one always had the will of another in the place of one’s own.”10 However, in Guantánamo subditio is organized around the scenic agon of wills, of the state and the prisoner, as a theater of dislocation; subditio is concentrated in the performativity of forced feeding, which foregrounds, frames, and conserves the resisting will of the hunger strikers, not just its terminal submergence: “The existence of the colonizer as subject is shot through with the easy enjoyment that consists in filling the thing with a content that is immediately emptied. The subject that the colonizer is, is a subject stiffened by the successive images he or she makes of the native.”11 The substance (I will not deign to call it sustenance or food) whose transfer mediates this agon of wills is literally a transmission of substantialized power.12 Thus it is no coincidence that the Guantánamo authorities have published weight-gain graphs of their prisoners as emblems of the clinical character of confinement and the value they accord to a sustainable warehoused terrorist body, however recalcitrant (fig. 1.1).13 Guantánamo prisoners who pretend that they are eating are termed “stealth hunger strikers” by the camp commander, connecting their resistance to their imputed and ongoing “terrorist” biopower.14 The photology of forced feeding deepens the occupation and spectrum dominance over the terrorist body by inserting “scopic” utensils (metal-tipped tubes) and compulsory state substances into the exposed and inverted interiority of the prisoner.

Figure 1.1. Weight graph of Ashraf Salim while imprisoned in Guantánamo. Source: U.S. Department of Defense

This subject-making project extends to the adjudication process of the CSRT itself, which is why the futurity of its verdicts effectively appear to precede the actual tribunal and are integrated into the veridiction procedure, which functions as an act of avowal not by the accused, but by the state. The state avows the subject of the tribunal through what can and cannot be said in accordance with secret knowledge. Two archives or two anterior verdicts, that of the classified information and that of the disciplinary infractions of the detainee, elaborate the effective jurisdictional right of the CSRT. Both these archives establish the incompetency of the detainee as an avowing subject, which is why this act is transferred to the tribunal, masquerading as an intermediary between the prisoner and sovereignty as exemplified by the counterfeit figure of the “personal representative.” In the post-Fordist, post-rehabilitative apparatus, any prisoner’s contestation of the CSRT, of its evidentiary or procedural validity, merely extends the institution’s design of the former’s crime.

Disframed and Disframing Sovereignty

At his tribunal Salim was informed that he would be tried on documents, “partially masked for security reasons,” to which he would have no direct or indirect access. The tribunal transcript (as mediated by an Arabic-English translator and the court stenographer) recorded his response:

DETAINEE: We are getting into things classified and unclassified. All this is just about me proving what I did. If I did the things I did, I would admit that I did. Things I didn’t do, I will say clearly I didn’t do them. But if the Tribunal is saying there are classified things, classified information—they have to prove that. I am not asking to see the witnesses, if you have any. I need just their names to prove your documents are true. I think this is not justice if you accuse some one based on the classified information. This is not justice; it is not right. It hasn’t been witnessed in the whole human history. If you base your judgment or the accusations against me on classified information, then there is no need to continue. Let’s just stop it right here.

TRIBUNAL PRESIDENT: Ashraf Salim, I have classified information that is being presented by the Government. If we release all of that information it could cause harm to the national security of the United States.

DETAINEE: What harm or danger could you expe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Enigmatic Dispersals

- Part I: Desisting Sovereignties

- Part II: Amputating Archives

- Part III: Committing Anthropology

- Index