eBook - ePub

Visualizing Disease

The Art and History of Pathological Illustrations

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Visual anatomy books have been a staple of medical practice and study since the mid-sixteenth century. But the visual representation of diseased states followed a very different pattern from anatomy, one we are only now beginning to investigate and understand. With Visualizing Disease, Domenico Bertoloni Meli explores key questions in this domain, opening a new field of inquiry based on the analysis of a rich body of arresting and intellectually challenging images reproduced here both in black and white and in color.

Starting in the Renaissance, Bertoloni Meli delves into the wide range of figures involved in the early study and representation of disease, including not just men of medicine, like anatomists, physicians, surgeons, and pathologists, but also draftsmen and engravers. Pathological preparations proved difficult to preserve and represent, and as Bertoloni Meli takes us through a number of different cases from the Renaissance to the mid-nineteenth century, we gain a new understanding of how knowledge of disease, interactions among medical men and artists, and changes in the technologies of preservation and representation of specimens interacted to slowly bring illustration into the medical world.

Starting in the Renaissance, Bertoloni Meli delves into the wide range of figures involved in the early study and representation of disease, including not just men of medicine, like anatomists, physicians, surgeons, and pathologists, but also draftsmen and engravers. Pathological preparations proved difficult to preserve and represent, and as Bertoloni Meli takes us through a number of different cases from the Renaissance to the mid-nineteenth century, we gain a new understanding of how knowledge of disease, interactions among medical men and artists, and changes in the technologies of preservation and representation of specimens interacted to slowly bring illustration into the medical world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visualizing Disease by Domenico Bertoloni Meli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

VISUALIZING DISEASE IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

This chapter explores some key themes related to the visual representation of disease in the early modern period by combining a thematic and a biographical approach. I focus on three major aspects; the new genre of Observationes and the cognate Historiae and Curationes, especially those marked as chirurgicae, offered a venue for focusing on case histories. The establishment of anatomical museums and collections including pathological specimens provided valuable material for instruction and comparison; this practice accelerated in the last third of the seventeenth century, with the development of novel preservation techniques. Finally, the rise of surgeons socially and in the main scientific societies of the time favored what I call a “doubly localistic” approach valuing visualization; while of course visual representations of diseased states were not the exclusive prerogative of surgeons, it was surgeons who played an especially prominent role both directly and indirectly, by promoting and advocating their perspective. These developments intersected and reinforced each other.

Two figures emerge as particularly significant at the endpoints of my account, Guilhelmus Fabricius Hildanus in the first third of the seventeenth century and Frederik Ruysch in the decades around 1700. While Ruysch is well known and has attracted a considerable amount of scholarship in recent years, Fabricius has been far less studied, despite his reputation at the time. Their activities touched on the three themes I have identified: despite major differences in the preservation methods available at their respective times, both established museums that have been carefully documented; Fabricius was a leading surgeon, while Ruysch was lecturer to surgeons; their publications include collections of Observationes, rely on their museums, and present a large number of illustrations, including pathological ones.

Preamble: Early Broadsides and Surgical Treatises

Publications with illustrations of diseased states came in different formats, from folio to duodecimo and from large collections to small ephemeral broadsides. Here I wish to provide a few introductory remarks about very early developments with no pretense to offering a comprehensive treatment. It may come as no surprise that up to the sixteenth century the most common form representation associated to disease was the uroscopy chart, often depicted in the form of a wheel with many beautifully hand-colored urine flasks. Such charts provided a careful description of color, whose role in ascertaining disease was discussed in the text in relation to the four humors, blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. The many editions and translations of Fasciculus medicinae (editio princeps, Venice, 1491) by German physician Johannes de Ketham, for example, included a uroscopy chart with over twenty flasks. Such charts, however, represent diseased states only in an indirect way; although their role declined in the sixteenth century, they show that physicians included images, even colored ones, when they perceived them to be intellectually significant to their practice.1

Broadsides were a popular print form often announcing monsters, portents, and marvels. The spread of the French pox at the end of the fifteenth century constituted a dramatic development; the depiction attributed to Albrecht Dürer of a victim of the disease in a 1496 broadside by the Nuremberg town physician Theodoricus Ulsenius was probably the first of its kind. It shows the victim flanked by Nuremberg’s coats of arms under a zodiac sign with the year 1484, pointing to the astrological cause of the condition. Even when the broadside was hand-colored, the visual clues remained rather general at best. In the early Renaissance broadsides rarely provided detailed visual representations of diseased states; their main focus was elsewhere, often with congenital malformations perceived as monstrous.2

Surgery is the medical specialty with an especially strong association with visual representation. Unlike physicians, surgeons used many mechanical tools and took pride in them: instruments are often given a prominent role in their treatises. Procedures too are often featured and provide rich documentation about wider issues such as venues and social status. Surgical operations before the mid-nineteenth century were limited: they involved removing external growths and tackling external and rarely some internal conditions, such as those associated with syphilis, for example, the urinary system, amputations, and bone afflictions. Moreover, surgeons were often the ones responsible for dissections and would therefore have been in the front line at postmortems. Overall, however, early surgical works focused more on instruments and procedures than on diseased states as such, and when these do appear, they tend to be rather schematic, though matters progressively changed.3

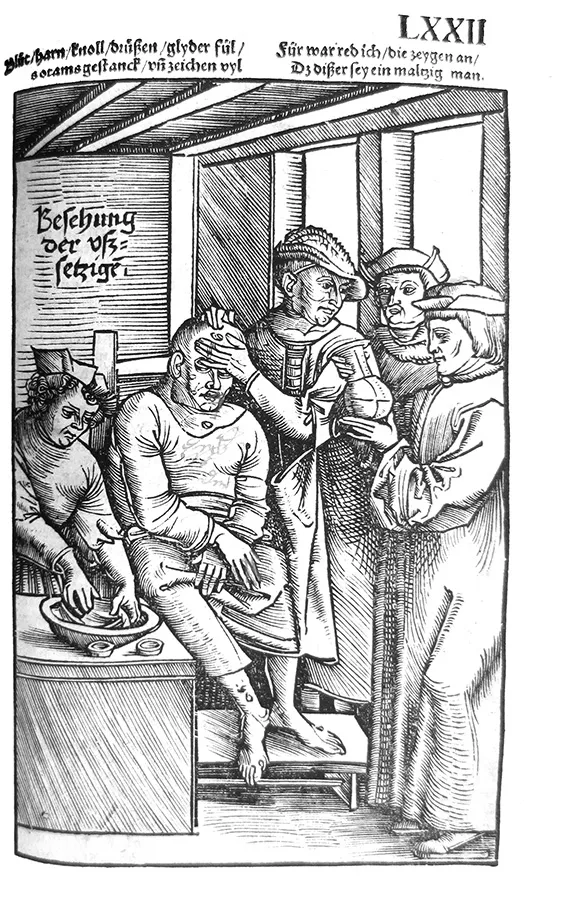

Illustration 1.1 Gersdorff, Feldbüch, 1517, [Hans Wächtlin?], page lxxii, leprosy. Woodcut.

At a time when images in medical books were emerging, they may have served a variety of didactic and practical purposes: the precise shape of surgical instruments would be practically relevant but also advertise the surgeon’s skill and equipment. Images of successful cures would obviously advertise the medical man’s skill. Procedures would show the proper set-up for patients and surgeons in a way that could be difficult to describe in words. Lastly, some images may have had a decorative or a mnemonic purpose, as the “wound-man,” with his impossibly large number of conditions, frequently shown in surgical works.

Feldtbüch der Wundtartzney (Strassburg, 1517) by military surgeon Hans von Gersdorff (ca. 1455–1529) is remarkable as an early example of both anatomical and pathological illustrations. Several plates in this surgery book show unusual attention to pathological conditions in live patients. Historian Luke Demaitre has argued that the woodcut of a leprosy patient in the Feldtbüch shows several procedures that would have unlikely occurred simultaneously (illustration 1.1). On the left possibly a barber surgeon washes a cloth that has been soaked in the patient’s blood; finding a sandy residue, or perhaps adherence of the blood to its container, would be a sign of leprosy. The two small cups in the foreground possibly contained salt and vinegar for assaying the blood by ascertaining whether it dissolved salt and whether vinegar changed its color. The patient, dressed in loose garments and in a pose reminiscent of Jesus surrounded by his tormentors, is being examined by a surgeon palpating his forehead while turning away to confer with the other people in attendance; his expression seems to express disgust at the patient’s stench, this being another diagnostic sign. Nodules are shown at different locations on his body, especially on the face, where they were deemed indicative of leprosy, but they are rendered schematically and without much detail. The next person on the right may be another physician or a public official; the last one on the right is a physician shown canonically while examining the urine flask.4 Overall, the nature of the condition is identified more by the text and setting than the actual lesions.

The later sixteenth century witnessed the appearance of major surgical works from such iconic figures as Ambroise Paré, surgeon to several French kings, Guido Guidi, active between Italy and France, Venice surgeon Giovanni Andrea della Croce, and Dresden oculist Georg Bartisch. Despite the exceptional quality and interest of some of the plates, overall their subjects eschew detailed representations of lesions. Guidi’s Chirurgia (Paris, 1544), for example, is an edition of ancient surgical works including images of conditions such as dislocations from the original manuscripts. Bartisch’s Ophthalmodouleia, oder Augendienst (1583), an ophthalmology treatise with numerous illustrations drawn by the author, includes images of instruments and procedures and occasionally also representations of eye diseases.5

Collecting and Visualization in Fabricius Hildanus

An especially significant figure in my story is Guilhelmus Fabricius from Hilden, or Hildanus (1560–1634), a prominent learned surgeon of his time. His publications in both Latin and the vernacular and extensive epistolary exchanges with prominent figures testify to his status. Fabricius lived a large portion of his life in Switzerland, first Geneva, then Payerne, and eventually Bern, where he became town surgeon and physician. Starting from the end of the sixteenth century, he published several works, notably a series of six centuriae of Observationes et curationes chirurgicae with many illustrations, and treatises on gangrene and dysentery; his Latin Opera (Frankfurt/M, 1646) was translated into French by Bonet in 1669, and a new revamped Latin edition appeared as late as 1713.6

Fabricius followed contemporary practices of learned physicians by publishing collections of Observationes and establishing a museum; in both areas, however, he adopted a surgical approach to documenting his practices and perspectives. He was among the first to characterize his Observationes as chirurgicae as opposed to medicae. Observationes were a new genre that emerged in the mid-sixteenth century, as Gianna Pomata has shown. They stem from the empirical tradition and focus on individual cases; they could make an unusual condition known to the medical community or advertise the success of the medical man in a difficult case. While following this tradition, Fabricius also developed it in new ways. Unlike their medical counterpart, surgical observationes focused on the manual intervention of the surgeon, often involving specially designed instruments that were illustrated together with the specific form of a growth, whether still attached to the body or removed; stones found in the bladder, kidneys, gallbladder, or other body parts; and broken or healed bones. Similarly, following the example of several Italian medical men and contemporary physicians and correspondents at Basel, such as Felix Platter (1536–1614), Caspar Bauhin (1560–1624), and Jacob Zwinger (1569–1610), Fabricius assembled a museum, which was located in his home; although we know that he also collected ancient coins, in his correspondence and publications he singled out a cohesive body of anatomical, surgical, and pathological items.7

Besides describing and at times providing images of several items in his Observationes, Fabricius left a detailed description of his museum in a letter to Leiden anatomist Pieter Paaw, including some of his preservation methods. At the time Leiden had an anatomical museum that Fabricius had visited. A few decades before Fabricius, Paré had used vinegar and alcohol for preservation, but his aim seems to have been embalming more than saving body parts for scholarly purposes. Fabricius relied on drying and stuffing cavities, from blood vessels to the digestive tract, with hemp and cotton. He also mentioned a white mole and a monstrous black sow preserved with aloe, myrrh, scordium, absinth, and hemp.8

With such limited preservation methods, it is not surprising that his museum consisted largely of stone formations and especially bones, both being largely surgical domains. All the items listed in his letter to Paaw were naturalia, except for an artificial eye he had constructed; he listed forty-eight individual items or collections of items—item twenty-three, for example, mentions more than thirty badly healed bones—for a total exceeding one hundred. The main organization criterion emerging from his letter to Paaw is the distinction between human and animal items: the first twenty-nine items list human parts, whether healthy or diseased, items thirty to forty-eight relate to a wide range of animals, which would display an analogy, proportion, and similarity with the human body. Very small animals display God’s knowledge, providence, and goodness; thus Fabricius’s museum joined cognitive and religious motivations. One item, thirty-seven, consists of a “monstrous” pig with double parts; Fabricius also wrote a pamphlet on a monstrous sheep, though it was not included in his Opera, where overall monsters do not play a significant role.9

Illustration 1.2 Fabricius Hildanus, Opera, 1646, page 2, eye tumor. Woodcut.

Fabricius included a large number of images in his works. Much like rare and remarkable specimens in his museum, or successful cures reported in Observationes, images enhanced his standing and provided valuable material for investigation and instruction. No doubt, they added to the appeal of a work for multiple reasons; in discussing the peculiar position of a fetus Fabricius defended their cognitive role, arguing that features that “are obscure from a description, can be better known from an image.” Some passages point to Fabricius relying on draftsmen, at times including noted Bern artist Joseph Plepp.10

The first case in Fabricius...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Bodies, Diseases, Images

- 1 Visualizing Disease in the Early Modern Period

- 2 “Sic nata est anatome pathologica picta”: The Diseases of Bones

- 3 Preserved Specimens and Comprehensive Treatises

- 4 Intermezzo: Identifying Disease in Its Inception

- 5 The Nosology of Cutaneous Diseases

- 6 Morbid Anatomy in Color

- 7 Comprehensive Treatises in Color

- Concluding Reflections

- Acknowledgments

- Illustration Credits

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index