The Myth of Spontaneity

The band is hot. Thirteen musicians and two dancers packed onto the stage of the Middle East Upstairs in Cambridge, MA’s hip Central Square neighborhood. Tonight is a Felabration: a celebration of the life and music of Fela Kuti.1 Boston’s Afrobeat band Federator N°1 is playing to a sold-out room while video screens project footage of the famous Nigerian musician and social activist. In one corner of the room is a Shrine to Fela, if you are determined enough to push your way through a roiling mass of shoulder-to-shoulder dancers to reach it. I grab a beer and join the dancers on the floor, moving to the strong funk groove laid down by the bass and the tight harmonies of the horns. At a signal from the singer, the tenor sax player steps forward and begins to solo, winding a fierce melody up and then down the range of his instrument, highlighting cross-rhythmic gestures. The crowd goes nuts, and the singer signals for him to take another chorus.

A young guy in a plaid shirt and skinny jeans leans toward me with the most enormous grin. “Outstanding!” he shouts over music. “Can you believe he’s just pulling this shit out of thin air?”

I nod and smile back; the saxophonist really is very good. But I suspect that what he’s actually doing is much more complicated, and much cooler than that!

Finding the Boundaries of Creativity

It’s hardly radical to claim that virtually no improvised music is wholly spontaneous. Unlike the bar brawler improvising weapons from chair legs and pool cues, or the intrepid dinner host improvising a new recipe for “tuna surprise” when, thirty minutes before his guests arrive, he discovers he has no tuna, we know that improvising musicians do not simply play slapdash with whatever materials are conveniently available. “You have to know the dasar, the basics, first,” my arja drum teacher Pak Dewa2 tells me. “You have to practice it to feel it,” his partner Cok Alit3 adds. The inadvertent side effect of using “the concept of improvisation as a universal cutting across cultural domains” (Nettl 1998, 2) is that the untrained listener assumes that the process is offhand or unconsidered. As Bruno Nettl amusingly but aptly notes: “We probably never should have started calling it ‘improvisation’” (Nettl 2009b, ix).

Yet even unplanned acts of drunken violence and improvised culinary art are based on models and structural understandings of the objects and actors involved. The bar brawler would think: “I wish I had something with which to hit this other person. Like a cudgel.” Not being a character in a video game and thus having no cudgel handy, she would search for an object that could fulfill the same function. The mind stores concepts as sets of properties and their associated values (see Sawyer 2007, 115). Properties and values of a cudgel would include shape: long and thin; material: metal or other hard substance; function: to hit things. The way in which ideas, memories, and their representations are mentally encoded allows the brain to conjure useful images that relate, in sometimes surprising ways, to current situations.4 Using what psychologists call conceptual transfer,5 the bar brawler would seek a replacement cudgel based on the values of that object’s properties: something well-shaped for gripping, light enough to lift and swing, and hard enough to inflict damage. A pool cue would work (a TV trope for the improvised bar weapon); a pigeon or a chocolate chip cookie would not. The bar brawler may have improvised a weapon off the cuff and with no preparation to the specific situation, but the choice was neither completely random nor a brilliant innovation in a vacuum; her cultural training and life experience had taught her what a good equivalent to a cudgel might be, and, with that knowledge and memory, her mind came up with a useful solution. It is well established among experimental psychologists, neuroscientists, and other scholars examining human creativity that creative acts and ideas, no matter how radical, are grounded in the familiar.

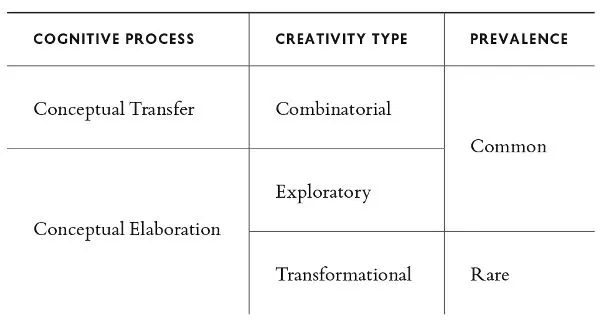

Cognitive scientists have shown that different kinds of creativity require the brain to process information in different ways. Combinatorial creativity involves combining familiar ideas in unfamiliar ways, as in visual collage, analogy, and poetic metaphor. A Balinese tembang macapat singer uses a comparable process when improvising new texts, mixing and matching familiar “devices and sources” and incorporating “resources built up” over time (Herbst 1997, 98 and 56). Likewise the gendér wayang player who has “a collection of small variations to phrases which may be used in alternation” (Gray 2011, 96). Such creative acts, through conceptual transfer, involve “projecting a ‘source’ (a familiar situation) onto a ‘target’ situation so as to help us learn about or think about the latter, or, if the ‘target’ does not yet exist, to create it” (Perlman 2004, 33). The bar brawler’s improvised weapon also falls into this category.

The other two primary forms of creativity, exploratory creativity and transformational creativity, are both grounded in specific conceptual spaces: structured, culture-based styles of thinking, such as the inherent rules of a genre of music. And both involve a creative mental process called conceptual elaboration, in which existing concepts are not simply mixed and matched, as in conceptual transfer, but modified in order to create something new (see Sawyer 2007, chap. 6). In exploratory creativity, the innovator comes up with new ideas within the confines of existing conventions, such as creating a new recipe, or reworking an old one, in the French style. A Balinese composer who reworks a gendér wayang piece in “fundamental ways, recreating [it] to such an extent that [it] could be said to be [a] new piec[e]” (Gray 2011, 189) is practicing exploratory creativity, as is that same composer creating a brand new composition in a known style, or a performer taking advantage of the “space” (97) in that composition to make alterations to it in the course of performance.

In transformational creativity, by contrast, the innovator alters some aspect of the conventions themselves in order to create the possibility of something more radically new.6 A thirteenth-century musician at Notre Dame Cathedral who maintained that 3rds and 6ths should be consonant instead of 4ths and 5ths could have created music considered impossible at that time, by changing just one defining dimension of the conceptual space of medieval music making. The new compositions would still be rule-bound, but the rules would now be altered. The contemporary Balinese composition mentioned in the previous chapter, in which a performer plays a gong with a metal grinder, is equally transformative. Such novel transformations, though, are extreme and relatively rare; “all artists and scientists spend most of their working time engaged in combinatorial and/or exploratory creativity” (Boden 2013, 8).7 Yet even the rare transformational kind is based on preexisting knowledge or conventions; new innovations are really just creative reworkings of culturally accepted or system-appropriate norms, patterns, and styles of thinking. Both combinatorial and exploratory creativity, and their associated cognitive processes, are relevant to a discussion of improvisation (table 1.1).8

Table 1.1 The types of creativity

Collective Creativity as Combinatorial and Exploratory

How do these concepts offer insight into specifically collective creativity? We learned in the previous chapter that many of the most original inventions happen through collaboration. Yet group genius need not involve direct contact between participants; innovation often evolves slowly, becoming a web of ideas and adaptations over time. Gottlieb Daimler’s internal combustion engine incorporated the hot-tube ignition system design of an English inventor named Watson, improving on Nikolaus Otto’s unwieldy four-stroke engine from twenty years earlier, which itself built on a design by Belgian engineer Jean Joseph Étienne Lenoir (see Diamond 1999, chap. 13; Clark 2010; Wise 1974). And “Edison didn’t invent the lightbulb; he found a bamboo fiber that worked better as a filament in the lightbulb developed by Sawyer and Man, who in turn built on lighting work done by others. . . . Inventors build on the work of those who came before, and new ideas are often . . . ‘in the air’” (Lemley 2012, 710 and 711). This kind of group genius emerges from a sort of invisible collaboration, where innovations from one place and time spread to influence innovators in another, and the combination of their ideas creates something neither could have created alone. The evolution of the mountain bike through the mid- to late 1970s is a case in point. Bikers in several places across the western United States began off-roading only to realize that the design of their road-racing bikes couldn’t sustain the terrain of a mountain. Each group started independently altering their bikes to improve the design, coming into contact with one another’s ideas over time:

The Morrow Dirt Club [of Cupertino, California] designed the gear-shifter and the new handlebars; the Marin County riders devised brakes that wouldn’t burn out; and several riders independently designed custom-made frames that wouldn’t break on the big bumps. . . . The mountain bike was the result of a largely invisible long-term collaboration that stretched from Marin to Colorado. (Sawyer 2007, 7)

Whether improvising a recipe in the moment or crafting a new invention over many years, creativity is a cumulative and imitative process, seldom truly cognitively transformational.

The same appears to be true of musical creativity, where invisible collaboration is key to idiomatic performance in well-established genres and styles. Arja drummers often attribute elements of their playing to the innovation of others. I Dewa Nyoman Sura of Pengosekan village often spoke to me of the many kendang patterns he had adopted over the years. Whenever he heard a great drummer, he once admitted, he would keep his ears open for notable patterns to incorporate into his own improvisations.9 “Dicuri!” he laughed, grabbing at the air between us with glee. “Stolen!” And Anak Agung Raka of Saba village once bragged to me how licik, sly, he was in borrowing other drummers’ concepts to then rework into his own playing. He described how he would meet master kendang players at the local warung kopi, coffee stand, buy them a cup of coffee, and begin a casual conversation about drumming. He would then encourage them to re-create, through mnemonics, their own patterns. Knowing that I sometimes transcribed his patterns after our lessons, he winked as he told me, “I write their patterns ...