eBook - ePub

Cartographic Japan

A History in Maps

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cartographic Japan

A History in Maps

About this book

Miles of shelf space in contemporary Japanese bookstores and libraries are devoted to travel guides, walking maps, and topical atlases. Young Japanese children are taught how to properly map their classrooms and schoolgrounds. Elderly retirees pore over old castle plans and village cadasters. Pioneering surveyors are featured in popular television shows, and avid collectors covet exquisite scrolls depicting sea and land routes. Today, Japanese people are zealous producers and consumers of cartography, and maps are an integral part of daily life.

But this was not always the case: a thousand years ago, maps were solely a privilege of the ruling elite in Japan. Only in the past four hundred years has Japanese cartography truly taken off, and between the dawn of Japan's cartographic explosion and today, the nation's society and landscape have undergone major transformations. At every point, maps have documented those monumental changes. Cartographic Japan offers a rich introduction to the resulting treasure trove, with close analysis of one hundred maps from the late 1500s to the present day, each one treated as a distinctive window onto Japan's tumultuous history.

Forty-seven distinguished contributors—hailing from Japan, North America, Europe, and Australia—uncover the meanings behind a key selection of these maps, situating them in historical context and explaining how they were made, read, and used at the time. With more than one hundred gorgeous full-color illustrations, Cartographic Japan offers an enlightening tour of Japan's magnificent cartographic archive.

But this was not always the case: a thousand years ago, maps were solely a privilege of the ruling elite in Japan. Only in the past four hundred years has Japanese cartography truly taken off, and between the dawn of Japan's cartographic explosion and today, the nation's society and landscape have undergone major transformations. At every point, maps have documented those monumental changes. Cartographic Japan offers a rich introduction to the resulting treasure trove, with close analysis of one hundred maps from the late 1500s to the present day, each one treated as a distinctive window onto Japan's tumultuous history.

Forty-seven distinguished contributors—hailing from Japan, North America, Europe, and Australia—uncover the meanings behind a key selection of these maps, situating them in historical context and explaining how they were made, read, and used at the time. With more than one hundred gorgeous full-color illustrations, Cartographic Japan offers an enlightening tour of Japan's magnificent cartographic archive.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cartographic Japan by Kären Wigen, Sugimoto Fumiko, Cary Karacas, Kären Wigen,Sugimoto Fumiko,Cary Karacas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART IV

Still under Construction

CARTOGRAPHY AND TECHNOLOGY SINCE 1945

Introduction to Part IV

Kären WIGEN

The rosy promise of pan-Asian prosperity that lit up Japanese children’s magazines in 1942 would soon be exposed as a sham. The very next year, the tide began to turn against Japan. The imperial navy’s attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor had already brought the United States into the fight, unleashing the fury of war across the Pacific. Early victories for the Japanese gave way to a string of defeats; by 1944 the front had reached the home islands. Guided by modified Japanese maps, American bombers blew up Japan’s factories and reduced its major cities to rubble in the space of half a year. The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of ’45 dealt the final blow. Within days, the emperor’s voice could be heard through the static on radios across the country announcing the unthinkable. Japan’s imperial dream—East Asia’s colonial nightmare—was over.

In the short term, defeat brought desperation to ordinary Japanese. Food, jobs, and shelter were all in short supply. The repatriation of six and a half million servicemen and colonists from Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria, China, and Southeast Asia only aggravated the crisis; for nearly five years, millions faced the very real prospect of starving. While the Allied Occupation could put democratic reforms in place by executive order, rebuilding homes and livelihoods proceeded at a crawl. But when war broke out on the nearby Korean Peninsula in 1950—on the eve of the treaty negotiations that would bring a formal end to the Occupation—Japanese industry came back to life. Factories that had once been slated for dismantling now went into high gear, making tanks and munitions for the US Army. Even after hostilities ground to a halt, Cold War strategists in Washington made sure that Tokyo retained access to the technology, capital, and markets the Japanese needed to rebuild their domestic infrastructure and manufacture consumer goods, for sale abroad as well as at home. With their new national constitution founded on the principles of human rights, democracy, and pacifism, the Japanese people were able to make a fresh start, initiating a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity.

So began the wide-ranging, long-running process of postwar landscape transformation that is the subject of part IV. For students of spatial history, the years after 1945 present a conundrum. On the one hand, documentation for this era is richer than for any previous time in the human past. In Japan as elsewhere, the cartographic archive grew exponentially in the later twentieth century; since the invention of the Internet, it has swelled yet again. On the other hand, the resulting embarrassment of riches gives us too much to take in. With millions of maps covering thousands of themes, a comprehensive overview recedes out of reach. Fundamental changes have been wrought, and mapped, in every sphere of Japanese life; only a few can be captured in a volume like this.

That said, the essays in part IV offer precious perspectives on an era of rapid change. While interested readers can readily turn elsewhere for studies of party politics, social movements, or international relations, the contributors to this final part of Cartographic Japan have elected to revisit some of the chief themes that have preoccupied Japan’s mapmakers since the Edo era: urban life, people on the move, sacred landscapes, and hazardous events. Along the way, their contributions illuminate the broad arc of postwar Japanese history, from recovery to growth to newfound vulnerabilities.

We begin with a look at the cartographic tools of US Army bombers in the final phase of the war (discussed in the chapter by Cary Karacas and David Fedman). The maps that facilitated the American campaign of incendiary air raids, from planning to damage assessment, took advantage of earlier topographic surveys undertaken by the Japanese government. Yet they are also among the first images of Japanese cities ever made by a conquering power. In one of many paradoxes that characterize this tragic era, these maps embody Japan’s role reversal from colonizer to colonized. Moving forward to the immediate aftermath of defeat, a map of occupied Tokyo from 1946 shows how the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers provided for thousands of foreign troops in the ruined capital (chapter by Cary Karacas).

Crucial though they were, food and housing were not the only urgent issues addressed during the Occupation. The US and its allies also moved swiftly to reorganize the symbolic landscape, stripping Shinto of its special political status and repurposing some sacred sites. As a prime symbol of the emperor-centered religion that had helped fuel Japan’s wartime ideology, Mount Fuji in particular became the subject of a protracted legal battle—one that began under the Occupation but continued for more than a decade afterward (chapter by Andrew Bernstein). Meanwhile, determined Japanese visionaries began making maps for the future. One plan drafted in the early postwar years redesigned Hiroshima around a commemorative peace park (chapter by Carola Hein); another laid out a whole new town on the rural outskirts of Osaka (chapter by André Sorensen).

By the time Senri New Town was built, Japan had entered a period of unprecedented double-digit economic growth, kicking off another wave of urban migration. Workers, students, and families from rural areas across the archipelago flocked to Japan’s newly rebuilt cities, with Tokyo emerging as by far the most powerful magnet. The sustained influx transformed the capital—a process brought into focus by our next group of essays. Starting with a snapshot of Tokyo’s overstrained road system on the eve of the 1964 Olympics (discussed by Bruce Suttmeier), successive authors highlight the proliferation of subway lines (Alisa Freedman), the struggle to sustain a traditional shopping district (Susan Paige Taylor), and the rise and demise of the city’s famed waterfront fish market (Theodore C. Bestor).

As Tokyoites began bracing for the 2020 Olympics, Japan found itself in the throes of yet another round of creative destruction. Most heavy industries had long since moved offshore in search of cheaper labor, the loss of manufacturing jobs only partially offset by new opportunities in the knowledge economy. Precariousness was the watchword of the day, as millions found themselves stuck in low-wage, part-time service jobs.1 Nor was fragility marked only in the economic sphere. Japan’s continuing vulnerability to natural hazards was made terrifyingly clear in the triple disaster (earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown) that struck northeastern Honshu on March 11, 2011.

That telling moment forms the backdrop for the volume’s concluding theme: new developments in the digital age. Our final section begins with a trio of essays on natural hazard cartography in the wake of 3/11, with individual authors probing the frontiers of earthquake forecasting (Gregory Smits), crowd-sourced mapping (Jilly Traganou), and a new genre of run-and-escape cartography (Satoh Ken’ichi). But just as the digital age has put powerful tools in the hands of citizens seeking to understand contemporary phenomena, so has it given new techniques to scholars seeking to understand the past. The mapmaking software known as geographic information systems (GIS) has opened new historical vistas, revealing spatial patterns in data that were collected during earlier periods but never before represented in cartographic form. One area where such techniques are being used to good effect is in the study of historical demography. In the case explored here by Fabian Drixler, plotting nineteenth-century stillbirth statistics reveals a lingering culture of infanticide that was essentially invisible until computer-assisted cartography came along. Reconstructions of this kind can be expected to illuminate many more corners of the Japanese past.

Meanwhile, complementing these data-driven applications of computer cartography are new forms of analysis for old maps. In our final pair of essays, Japanese scholars Nakamura Yūsuke and Arai Kei—pioneers in this line of research—recount recent breakthroughs in the study of the kuniezu, the massive manuscript maps of the provinces introduced in part I. Digital scanners have proven a boon to students of these fragile and unwieldy materials, allowing for unprecedented magnification and side-by-side comparison of widely scattered documents. Moreover, with painstaking care, these scholars and their students have launched a novel project to reconstruct provincial maps at full scale. Recounting the excitement of their discoveries, the final essays in the volume leave us at the cutting edge of Japanese historical cartography today—bringing us back full circle to the archival treasures with which Cartographic Japan began.

Note

1. Anne Allison, Precarious Japan (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

44. Blackened Cities, Blackened Maps

Cary KARACAS and David FEDMAN

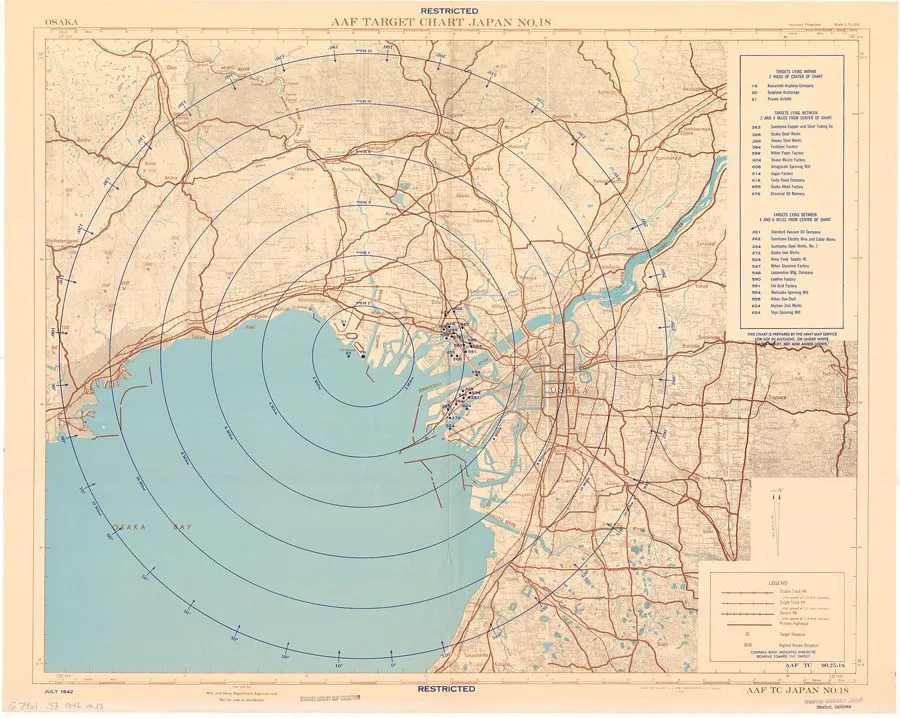

FIGURE 44.1. “AAF Target Chart Japan No. 18e Osaka,” July 1942. Army Map Services, US Army. 57 × 68 cm. Courtesy of Branner Earth Sciences Library, Stanford University.

For many among the first wave of American soldiers and civilians to arrive in Tokyo following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, words failed to convey the ruinscapes they encountered. “There is really no way to describe a bombed-out city,” wrote photojournalist John Swope. “There is simply nothing left—that’s all there is to it.”1 Perhaps no one painted a portrait of this destruction more vividly than the New York Times reporter George Jones, who wrote in a dispatch from Tokyo, “There should be no mistaken interpretation of the word ruins. There were blocks on which not a single building stood, where the construction and civilization wrought in the past centuries had been obliterated, leaving reddish soil—and nothing else.”2 Although observations of this sort focused principally on the capital and the two cities destroyed by nuclear bombs, urban wastelands stretched across the Japanese archipelago. By war’s end, the US Army Air Forces (AAF) had targeted sixty-six cities for destruction by incendiary bombing.

Initially, military strategists did not imagine striking such a blow to the Japanese homeland. “Use of incendiaries against cities,” Henry Arnold, the AAF’s top commander, had professed, “is contrary to our national policy of attacking only military objectives.”3 Although as early as the 1930s some strategists had noted the vulnerability of Japanese cities to fire, the AAF in the Pacific prioritized the high-altitude precision bombing of Japan’s aircraft engine plants, to be followed by “other war-making targets.”4 This is reflected in a substantial set of target maps of Japanese metropolitan areas created by the US military starting in 1942 as they planned the coming air war.

“AAF Target Japan No. 18e Osaka” (fig. 44.1), one of many such maps produced in 1942, visually conveys this strategic doctrine. The dots sprinkled throughout the concentric circles mark the location of military installations and industrial sites in the greater Osaka area, including munitions depots, billeting facilities, and chemical plants. This particular map centers on a target undeniably martial in nature: the Kawanishi aircraft plant, one of the region’s largest manufacturers of airplane parts. In addition to conveying the AAF’s focus on military sites, the map also hints at how new forms of spatial intelligence allowed for the production of a wide array of wartime cartography. In this instance, army cartographers relied heavily on Japanese cadastral survey maps, the likes of which cartographers and other specialists within the intelligence community—esp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- A Note on Japanese Names and Terms

- Introduction

- I. Visualizing the Realm: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries

- II. Public Places, Sacred Spaces

- III. Modern Maps for Imperial Japan

- IV. Still under Construction: Cartography and Technology since 1945

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Index