- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Relative to the other habited places on our planet, Hawai'i has a very short history. The Hawaiian archipelago was the last major land area on the planet to be settled, with Polynesians making the long voyage just under a millennium ago. Our understanding of the social, political, and economic changes that have unfolded since has been limited until recently by how little we knew about the first five centuries of settlement.

Building on new archaeological and historical research, Sumner La Croix assembles here the economic history of Hawai'i from the first Polynesian settlements in 1200 through US colonization, the formation of statehood, and to the present day. He shows how the political and economic institutions that emerged and evolved in Hawai'i during its three centuries of global isolation allowed an economically and culturally rich society to emerge, flourish, and ultimately survive annexation and colonization by the United States. The story of a small, open economy struggling to adapt its institutions to changes in the global economy, Hawai'i offers broadly instructive conclusions about economic evolution and development, political institutions, and native Hawaiian rights.

Building on new archaeological and historical research, Sumner La Croix assembles here the economic history of Hawai'i from the first Polynesian settlements in 1200 through US colonization, the formation of statehood, and to the present day. He shows how the political and economic institutions that emerged and evolved in Hawai'i during its three centuries of global isolation allowed an economically and culturally rich society to emerge, flourish, and ultimately survive annexation and colonization by the United States. The story of a small, open economy struggling to adapt its institutions to changes in the global economy, Hawai'i offers broadly instructive conclusions about economic evolution and development, political institutions, and native Hawaiian rights.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hawai'i by Sumner La Croix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Short History of Humans in Hawaiʻi

Humans have a very short history in Hawaiʻi. The Hawaiian archipelago was the last major land area on the planet to be settled when Polynesians traveled over 2,000 miles north to the islands about 750–850 years ago. Just 50 years ago, our understanding of the social, political, and economic changes that unfolded over the next eight centuries was limited by how little we knew about the first four to five centuries of settlement. Today, a series of snapshots of Hawai‘i’s early history has emerged due to extensive excavations by archaeologists, scientific advances in dating archaeological remains, and remarkable connections made between the new physical evidence and oral stories passed down across generations of Hawaiians. A series of insightful and ambitious recent studies has woven these historical snapshots into more coherent historical narratives. These synthetic narratives have, in turn, awakened us to the importance of grasping the full sweep of Hawai‘i’s history: knowing more about the economic and political institutions in place centuries earlier allows us to see clear linkages between those early institutions and today’s institutions and outcomes.

Some linkages are obvious. When we look at the ponded taro fields at Hanalei, Kaua‘i, we see not just today’s taro fields but also the outlines of the irrigation systems put in place in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by the new immigrants from East Polynesia and their descendants. A tour of these fields quickly informs us how remarkably productive they still are today. Our new understanding of Hawaiian history allows us, however, to connect the high productivity of these fields today with their high productivity 700 years earlier. The surpluses generated by these taro fields 700 years ago allowed an economically and culturally rich society to emerge and flourish, and the rich inheritance of these ancient institutions is reflected in the productivity of today’s farmers at Hanalei.

Important connections between the distant past and the present have been found in societies around the globe. Consider that one of the very best “predictors of an individual’s income today is the level of riches attained by that person’s ancestors hundreds of years ago.”1 Consider African tribes that captured and sold people from other tribes for the slave trade during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Today, the countries that encompass those societies have governments than tend to be more authoritarian and citizens who tend to be poorer and have less trust in one another than citizens of other African countries.2 Consider the German villages where Jews were massacred during the fourteenth-century Black Death. They turn out to be the same German villages where Jews were terrorized during the 1920s and citizens voted for the Nazi Party.3

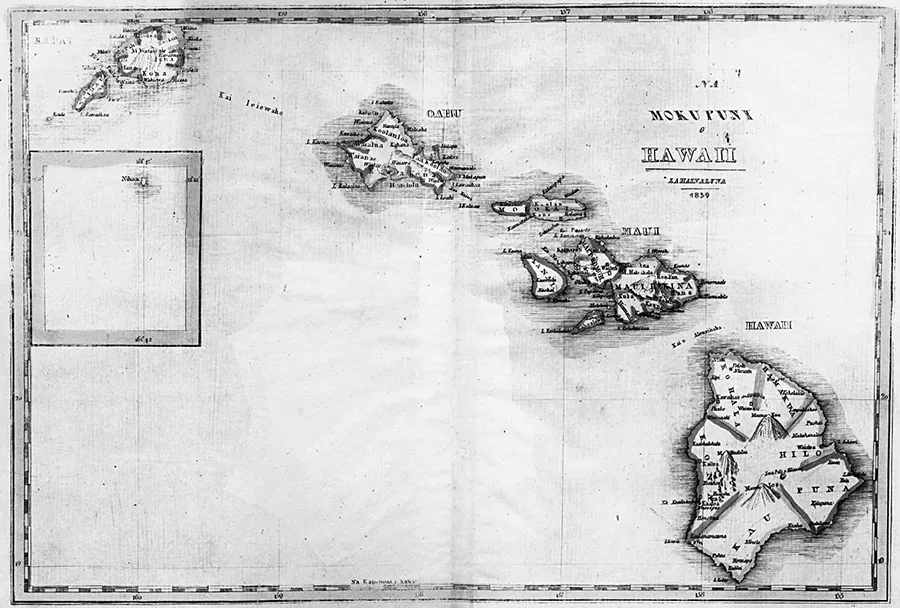

The linkages between the past and present in Hawai‘i’s political history are also quite remarkable. Archaeologists and historians now date the emergence of centralized political institutions on the island of O‘ahu from sometime in the fifteenth or early sixteenth century, more than 500 years ago. Small, resource-rich chiefdoms, each supported by a state religion, merged into larger states and competed with one another for the next 350–400 years to control more territory and people within the eight major Hawaiian islands (fig. 1.1). In these well-organized states, property rights in land were well specified and enforced, and a system of post-harvest taxation facilitated risk sharing and mobilization of state resources for war. We see these well-functioning institutions mirrored in today’s sophisticated political institutions and high living standards. The maka‘āinana, the people who worked the land, had living standards with levels of nutrition and leisure that probably equaled or exceeded those of peasants in England. In 2018, the typical Hawai‘i household continues to have a standard of living exceeding that of the typical English household.

FIGURE 1.1. Na Mokupuni O Hawaii [Map of the Hawaiian Islands], 1839. Drawing: Lahainaluna Prints. Source: Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library.

Three more general features of Hawai‘i’s past political institutions are reflected in its twenty-first-century political institutions. First, today’s political institutions reflect the centralization of those that emerged 500–600 years ago, as the state government cedes few powers to Hawai‘i’s four county governments, and the state constitution endows the state governor with more powers than governors in other states hold. Second, ruling chiefs used land redistribution as a mechanism to form and preserve ruling political coalitions in ancient Hawai‘i. Land redistribution was the lubricant that allowed a ruling chief to respond to changes in the political power of powerful chiefs and their supporters. What is striking is how land redistribution continued to be used as a mechanism to stabilize ruling coalitions when Hawai‘i was unified by King Kamehameha in 1795, when King Kauikeaouli reorganized property rights and modernized the government in the 1840s, when the territorial colonial government took the crown lands in 1898, and when the new state government acted in 1967 to allow homeowners to force the sale of leased land under their homes. Today, politicians forgo explicit redistribution of land to stabilize their political coalitions, relying instead on the dual application of state and county land use laws to distribute above-normal economic returns—economic rents—to favored parties. Finally, Hawai‘i’s early political institutions reflected its origin as a society of immigrants who established independent settlements that were neither controlled by nor dependent on their home governments. It is striking that despite over 75 years of colonial rule in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, independent political institutions and ambitions re-emerged with the push to statehood in the 1950s, and more are emerging with the more recent push by Hawaiian sovereignty groups to achieve self-determination.

Independence is also an early theme in Hawaiian history, as the population was founded by Polynesians who embarked on long, risky voyages in hope of finding a new home. The voyages to Hawai‘i are now recognized as among the last waves in a pulse of voyages and settlements of East Polynesia that happened during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries. It had been more than 1,500 years since Polynesians had undertaken voyages that discovered new archipelagos, but suddenly there came pulses of voyages to the north (Hawai‘i), to the southwest (New Zealand), and to the southeast (Rapa Nui, also called Easter Island). From about 1200 to about 1300–1400, voyages between Hawai‘i and the newly settled Marquesas Islands and Society Islands brought new immigrants, plants, technologies, culture, language, and political and economic institutions to Hawai‘i (see chap. 2).4 From the archaeological record and ancient oral traditions, the archaeologists Timothy Earle and Patrick Kirch have constructed compelling narratives of the establishment of new communities by Polynesians in their newly found islands. An emerging body of evidence suggests that the first waves of Polynesian immigrants transformed Hawai‘i’s environment, burning lowland forests and harnessing streams in mountain valleys to create thousands of ponded taro farms, fields of sweet potatoes and yams, and groves of breadfruit trees.

The original Polynesians carried their culture, plants, animals, technologies, and political institutions with them on their voyages to re-establish their societies when they found their new island homes.5 They came to the islands with well-established norms of behavior and clear understandings of how governments and societies functioned on their home islands, all of which possessed natural environments not that different from those they found in Hawai‘i. The immigrants were far enough separated from their homes by distance and the risks of voyaging that they surely discounted rule from the home country as a possibility. From the beginning, they must have assumed that their new settlements would be autonomous, yet surely could not have imaged how completely isolated from other societies they would become.

The Polynesians settling Hawai‘i did what migrants to new lands who come from established societies always do: they re-created the societies, polities, and institutions of their homelands during their early years of settlement. There is only fragmentary evidence regarding post-discovery contacts between Hawai‘i and Polynesia, but archaeologist Patrick Kirch has pointed out an array of connections that reinforce oral traditions of cultural transfer (e.g., religious traditions brought by the priest Pā‘ao from Tahiti, the pahu drum and temple rituals brought by La‘amaikahiki, and breadfruit seedlings brought by Kaha‘i), technological transfer, and perhaps trade (e.g., volcanic glass adzes mined from the Mauna Kea quarry during the 1300s found in the Marquesas and an adz mined on Kaho‘olawe found in the Tuamotu Archipelago).6 With the transformation of the environment and the rapid expansion of farming and settlement came rapid population growth.7 Archaeologists studying the first 100–150 years of settlement contend that most of the valuable lands had been claimed by 1400, setting the stage for changes in the returns to laborers and landowners and, consequently, the overall political environment.

After voyagers and their descendants re-established the political and economic orders of their homelands in Hawai‘i, an unthinkable and incredibly rare event unfolded: for roughly 350–400 years, Hawaiians had no contact with the rest of Polynesia and, for that matter, the rest of the world.8 Hawaiians are one of only a very few people in world history who have ever become isolated from other societies solely due to changes in the climate and the ocean that affected their abilities to navigate beyond the islands and other peoples’ abilities to navigate to Hawai‘i.9 Perhaps the winds in the Northeastern Pacific Ocean changed, or perhaps the Polynesian peoples in the Eastern Pacific Ocean began to view long-distance voyaging as more risky or less profitable. Whatever the reasons for the end of voyaging, flows of migrants, ideas, and trade to and from Polynesia stopped completely for about three to four centuries. During these 300–400 years, the Hawai‘i population grew rapidly (see chap. 3), which means that many families had large numbers of children. Losing the opportunity to migrate was a big loss for these large generations, as they were forced to compete for land in Hawai‘i rather than voyage to discover and settle new archipelagos.

Closure of the migration option probably had several other important effects. It could have been important in the fifteenth century when O‘ahu chiefs consolidated their control because it left O‘ahu farmers with one less option to resist attempts by the chiefs who managed the land to extract more income from them. Isolation from other peoples in Polynesia meant that there were fewer ideas in circulation and no one from other societies visiting who might directly or indirectly raise questions about the increasingly exalted status of Hawai‘i’s chiefs (ali‘i). Isolation meant that it was easier for ruling chiefs to legitimize the ideology that enshrined their exceptionally differentiated status.10 And isolation also meant the end of trade in valuable goods, as voyaging canoes were not suited for long-distance transport of staple goods. An end in the trade for valuable goods such as volcanic glass adzes would have reduced the incomes of highly skilled craftsmen and left them more dependent on trade with high-ranking chiefs, again strengthening the chiefs’ wealth and power.

The several Hawaiian states that were competing for power by the fifteenth century had evolved in a direction quite different from their Polynesian counterparts in Tahiti or the Marquesas Islands, developing more features like those seen in the states in central Mexico in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries that consolidated into the Aztec Empire, the competing Wankan states that emerged in the upper Mantaro Valley in Peru in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, or even the Egyptian Pharaonic state during the Second and Third Dynasties.11 In all of the newly consolidated states in Hawai‘i, there developed a sharply differentiated elite (ali‘i) whose social rank and privileges were far above those of the main body of the population (kānaka maoli). When ali‘i passed through a village, kānaka maoli had to lie face down on the ground or face execution. The ali‘i’s divine connections were supported by a state religion and an elaborate system of genealogical mapping denied to the rest of the population.12 These cultural developments pose a central question for the study of Hawai‘i’s history: What was it about isolation and internal conditions in Hawai‘i that led to the development of a society with such huge gaps in status between the 1–2 percent of the population who ruled and those who worked the land?

My analysis of this question follows in the wake of a huge literature generated by a small army of archaeologists who have extensively probed the origins of archaic states in Hawai‘i.13 Chapter 3 reviews archaeologists’ theories and evidence regarding the origins of archaic states in Hawai‘i and considers how the widespread warfare among these states affected the institutions that evolved, and vice versa. All of the Hawaiian states were theocracies, in which religious and state officials were part of the same overall organization. A critical feature of the archaic state’s architecture was its ritualized system of taxation during the New Year’s festival (makahiki), which facilitated extraction of economic surplus and preparations for war. The integration of political authority with a state religion to build tens of thousands of s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- chapter 1. The Short History of Humans in Hawaiʻi

- chapter 2. Voyaging and Settlement

- chapter 3. The Rise of Competing Hawaiian States

- chapter 4. Guns, Germs, and Sandalwood

- chapter 5. Globalization and the Emergence of a Mature Natural State

- chapter 6. Treaties, Powerful Elites, and the Overthrow

- chapter 7. Colonial Political Economy: Hawaiʻi as a U.S. Territory

- chapter 8. Homes for Hawaiians

- chapter 9. Statehood and the Transition to an Open-Access Order

- chapter 10. The Rise and Fall of Residential Leasehold Tenure in Hawaiʻi

- chapter 11. Land Reform and Housing Prices

- chapter 12. The Long Reach of History

- Appendix: A Model of Political Orders

- Notes

- References

- Index