![]()

1. The Dream of the Information World

The world is really going to hell in a toboggan, and I’m putting these boxes together. . . . But, you know, that’s not the point. The point is . . . [that the idea is] followed absolutely to its conclusion, which is mechanistic. It has no validity as anything except a process in itself. It has nothing to do with the world at all.—Sol LeWitt (1969)

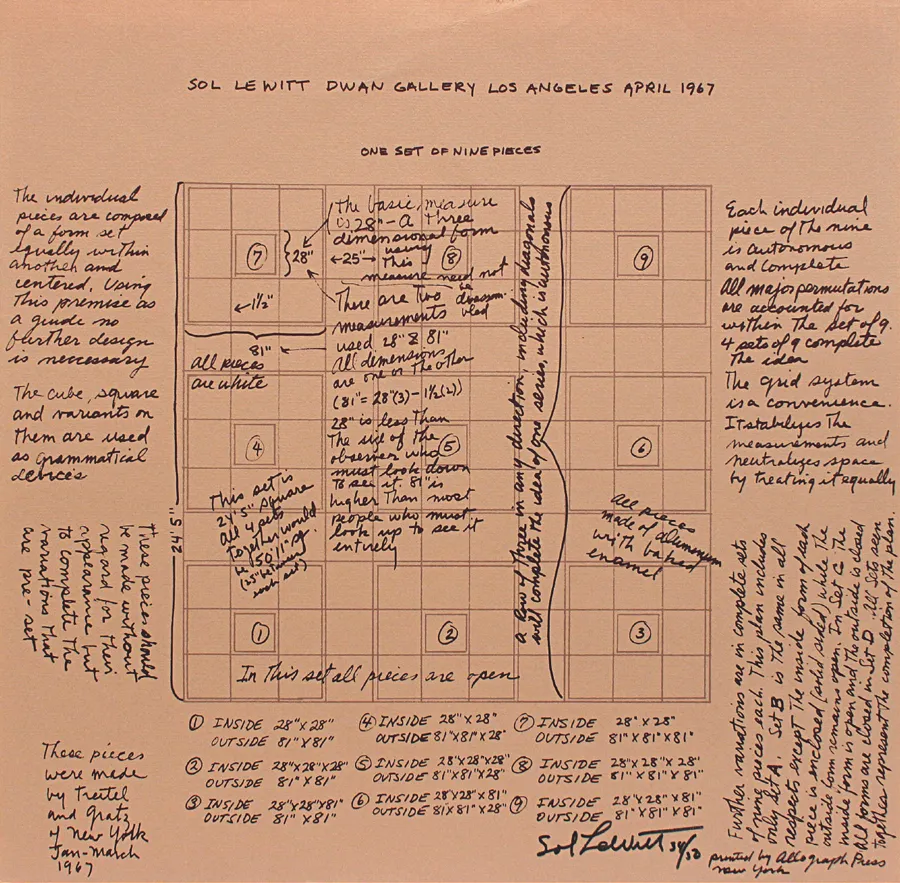

Look at a print of a drawing produced by Sol LeWitt in 1967, and then used as the announcement for an exhibition of his work at the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles that year (fig. 1.1). The drawing is a plan for four sets of nine pieces. One of these sets LeWitt has described graphically in both gridded form and written language. Take a grid, subdivide it into nine smaller, equivalent grids, then mark off each as its own isolated “piece.” LeWitt has done just this, and then he has numbered the pieces from one to nine—a designation that appears to be their only distinguishing mark. Otherwise, these pieces appear to be completely identical, having been produced by the grid’s fail-safe system of equivalences.

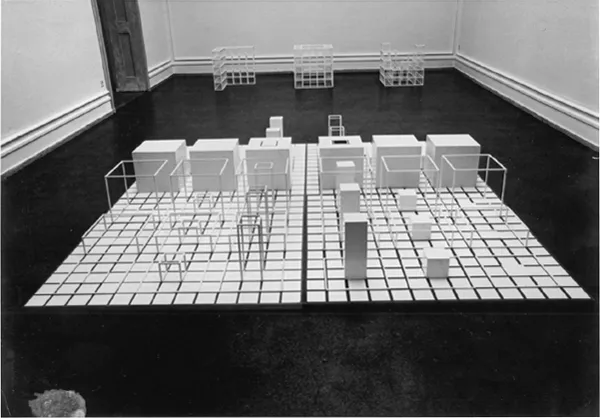

But look more closely and you’ll see that LeWitt’s drawing is actually asking us to imagine these nine pieces as distinct—he indicates this with a list of measurements jotted at the foot of the print. In fact, this set of nine pieces is more like Serial Project #1 (ABCD) from 1966–68 than the grid diagram would have us think (fig. 1.2). Each piece in the print is defined by the uniqueness of its variation. Like Serial Project, the print represents a field of cubic forms that rise to incremental heights, in the way an urban landscape or miniature architectural model appears from above. But the drawn set would be better described not as architectural or even inhabitable, but as structural. In fact, the artist prefers the term “structure,” to the more usual one, “sculpture.”1

1.1 Sol LeWitt, announcement card for Sol LeWitt exhibition at Dwan Gallery, 1967. Printed announcement, 35.6 × 35.6 cm. © 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston.

1.2 Sol LeWitt, Serial Project #1 (ABCD), 1966–68. Painted steel, 9.5 × 70 × 70 in. Westfalisches Landesmuseum, Münster, Germany. © 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

By 1967, the year LeWitt created this particular structure, the rules of structural order were widely and readily applied to nearly every field of cultural inquiry—mathematics, the empirical sciences, the social sciences, especially anthropology and psychology, and of course linguistics. In fact, by that year practitioners from a wide range of fields were calling upon the laws of structural order to examine and explain an extraordinarily vast range of cultural phenomena. In 1968 Jean Piaget, among many others, sought to define what exactly a structure is. In his terms, a structure is “not a mere collection of elements and their properties,” but rather it “involve[s] laws: the structure is preserved or enriched by the interplay of its transformation laws, which never yield results external to the system nor employ elements that are external to it.”2 The kind of structure I see LeWitt employing accords with Piaget’s definition; it is a system of transformations. Looking closely at LeWitt’s set of nine pieces, we can grasp that his grid’s law of equivalences is actually used to spawn differences. There are only differences in LeWitt’s structure. The meaning of each piece is not immanent in it, much in the same way that structuralist linguistics teaches us that the letters that form the word “cat” have no intrinsic meaning; they mean because they are not “cap” or “cad” or “bat.” Furthermore, both field and module in LeWitt’s structure are organized in such a way that precludes breaking the system, for the elements of any structure are always subordinate to its laws. Piaget explains that the elements “do not exist in isolation from one another, nor were they discovered one by one in some accidental sequence and then, finally, united into a whole. They do not come upon the scene except as ordered.”3 We could say, therefore, that LeWitt’s structure is predicated on the obdurate incontestability of the peculiar temporality of its order—always-already present as whole, like a grid whose elements come into being together and all at once, in an extraordinarily democratic way, in the very moment that the horizontal-vertical pattern is laid down. Moreover, to consider any one piece from LeWitt’s set will always be an activity inextricable from the conceptual integrity of the whole.

Be sure to notice, as well, that LeWitt’s grids do not actually operate for the work of art like a framework, as in the case of a picture rendered in one-point perspective; the grid structure does not function, as Lawrence Alloway has put it, “as the invisible servicing of the work of art.” Rather, the grid structure is, as Alloway says, the “visible skin” of the work. He adds, emphatically, “it is not . . . an underlying composition, but a factual display.”4 And so if LeWitt’s structure pictures a world—as I want to suggest it does—it does not do so in the way that we ordinarily associate with pictures. His grid does not serve as the armature for a scene represented, or for a ground with or without figures upon it. In fact, if LeWitt’s structure could be said to indicate anything at all, it would be the very assurance that everything has been brought to the surface, or better, that the relationship between surface and depth, disclosure and hiddenness, visibility and invisibility, has been extinguished. LeWitt’s grid declares that “everything is here.” And it does so with a self-generated sense of autonomy, like a miniature world created ex nihilo. Even if we can’t actually see it, everything is accounted for by the structural system, everything has been subsumed into its order of equivalences. Everything has been brought into absolute visibility, only now visibility is not a property of looking or even of the visual, but a figure of epistemic mastery.

This reconfiguration of the visible is critical here, not just for the self-definition of so-called conceptual art, but, more importantly, for the world-view out of which LeWitt’s grid and so many other works of art like it grew. LeWitt’s grid renounces the visual and, in its place, proposes that there is a deeper, structural logic governing its form that cannot, nor even need, be seen with our eyes. In 1967, just one year after the year most often cited as the start date for conceptual art, LeWitt turned this sort of practice into something of a mantra: “What the work of art looks like isn’t too important.”5 His language seems straightforward; he explains that, on the one hand, there is an art of the mind and, on the other, an art of the eye. LeWitt was not alone in making statements such as this; his words may stand in here for those of dozens of practitioners who might have said the same: Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, and Douglas Huebler come first to my mind. “Art is not necessarily a visual experience,” Huebler proclaimed two years later. “Art [is] the thing that comes into your head—and not . . . a visual thing. You see, by using the visual thing and then suspending it, then the art has to be located in the idea and away from the visual appearance, you see.” For Huebler, even seeing is not a thing of vision, but a figure of speech for grasping the concept.6 Indeed, LeWitt reiterated his disavowal of the visual within this very print. “These pieces should be made without regard for their appearance,” he scrawled alongside the grid plan—as if to announce, along with the opening of his show at the Dwan Gallery, that we won’t find what we’re looking for by looking.7 Appearances should be disregarded.

Above all, it is the look of LeWitt’s print that nearly causes us to overlook the obscurities of his language and swallow whole his stated disavowal of the visual. On first glance, it seems there is nothing to look at in the work; it is too lean, too stripped, too “pre-fact[ual],” to use his word—always before something else that never fully arrives.8 Or perhaps it is because when one looks, as Donald Kuspit has surmised, “one does not so much see [the work] as think about [it], in part because the seeing . . . is quickly and fastidiously done.”9 And when we do look, we quickly come up against the challenges of description. “It’s like getting words caught in your eyes,” wrote Robert Smithson after laying his eyes on this print.10

But what if we asked—in spite of LeWitt’s derogation of the visual, in the face of language’s recalcitrance to being looked at, over and against the elusive transparency of the grid—what does the print look like? If we are to see this print as a species of the visual and understand the world that its aesthetic pictures, then we will have to read its structure with an eye to form, as one reads a dream. We will have to attend to the strategies of withholding that have shaped that which is, despite all claims to the contrary, certainly given to be seen.

To show how the visual matters to this work and so many others like it, I will advance three claims, each describing what LeWitt’s print “looks like.” Then, by way of an examination of the Information show, held at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1970, I will elaborate the depth of their significance and explain what each has to do with the others. My first claim: LeWitt’s Untitled looks like information. This is not just because the drawing informs us of the rules and specifications for the nine pieces, but also because the print has the look of information—to rethink Kuspit’s figuration “the look of thought.”11 As I will elaborate shortly, this “look of information” permits us to understand the technological imaginary of its historical moment.

My second claim will come as no surprise to readers of conceptual art: this drawing also looks like language. This is not merely because the drawing is largely composed of written form, but also because it has the look of language. To understand this idea, we will need to consider carefully the structuralist imaginary of this historical moment—the range of cultural forms language was said to represent and encompass, and the ways in which it was understood to perform that representation. And lastly, my third claim: LeWitt’s Untitled print also looks like a work of art in a time of crisis, at least a late twentieth-century rendition. “The world is really going to hell in a toboggan,” the artist said in a 1969 interview with Patricia Norvell, “and I’m putting these boxes together. . . . But, you know,” he continues, “the point is [that the idea is] followed absolutely to its conclusion, which is mechanistic. It has no validity as anything except a process in itself. It has,” he concludes, “nothing to do with the world at all.”12 This look, I will explain, has everything to do with the world: not just contemporary events, movements, and catastrophes, of which there were so many at this time, but also the way in which we conceive of the world—not if it exists, for that would be to return to the inquiry of Descartes’s “Meditation VI,” in which the existence of the world is predicated on its presence to his faculty of knowledge alone, as he says, “t...