- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Is it in our nature to be altruistic, or evil, to make art, use tools, or create language? Is it in our nature to think in any particular way? For Daniel L. Everett, the answer is a resounding no: it isn't in our nature to do any of these things because human nature does not exist—at least not as we usually think of it. Flying in the face of major trends in Evolutionary Psychology and related fields, he offers a provocative and compelling argument in this book that the only thing humans are hardwired for is freedom: freedom from evolutionary instinct and freedom to adapt to a variety of environmental and cultural contexts.

Everett sketches a blank-slate picture of human cognition that focuses not on what is in the mind but, rather, what the mind is in—namely, culture. He draws on years of field research among the Amazonian people of the Pirahã in order to carefully scrutinize various theories of cognitive instinct, including Noam Chomsky's foundational concept of universal grammar, Freud's notions of unconscious forces, Adolf Bastian's psychic unity of mankind, and works on massive modularity by evolutionary psychologists such as Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, Jerry Fodor, and Steven Pinker. Illuminating unique characteristics of the Pirahã language, he demonstrates just how differently various cultures can make us think and how vital culture is to our cognitive flexibility. Outlining the ways culture and individual psychology operate symbiotically, he posits a Buddhist-like conception of the cultural self as a set of experiences united by various apperceptions, episodic memories, ranked values, knowledge structures, and social roles—and not, in any shape or form, biological instinct.

The result is fascinating portrait of the "dark matter of the mind," one that shows that our greatest evolutionary adaptation is adaptability itself.

Everett sketches a blank-slate picture of human cognition that focuses not on what is in the mind but, rather, what the mind is in—namely, culture. He draws on years of field research among the Amazonian people of the Pirahã in order to carefully scrutinize various theories of cognitive instinct, including Noam Chomsky's foundational concept of universal grammar, Freud's notions of unconscious forces, Adolf Bastian's psychic unity of mankind, and works on massive modularity by evolutionary psychologists such as Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, Jerry Fodor, and Steven Pinker. Illuminating unique characteristics of the Pirahã language, he demonstrates just how differently various cultures can make us think and how vital culture is to our cognitive flexibility. Outlining the ways culture and individual psychology operate symbiotically, he posits a Buddhist-like conception of the cultural self as a set of experiences united by various apperceptions, episodic memories, ranked values, knowledge structures, and social roles—and not, in any shape or form, biological instinct.

The result is fascinating portrait of the "dark matter of the mind," one that shows that our greatest evolutionary adaptation is adaptability itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dark Matter of the Mind by Daniel L. Everett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Psycolinguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226526782, 9780226070766eBook ISBN

9780226401430PART ONE

Dark Matter and Culture

1

The Nature and Pedigree of Dark Matter

Adherence to an epistemology is not something which merely ‘happens to a person but instead it reflects a component of his moral development. In some sense he is . . . morally responsible for adopting an epistemology even though it can neither be proved nor disproved to the satisfaction of those who oppose it.

KENNETH PIKE, With Heart and Mind: A Personal Synthesis of Scholarship and Devotion

This chapter provides a definition and pedigree of the notion of dark matter, tracing two broad clades of descent—the Platonic and the Aristotelian. I align my own work with the Aristotelian, empiricist line, arguing in favor of this tradition throughout the remainder of the book.

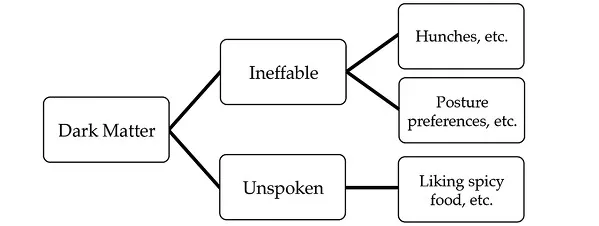

The first section of the chapter looks at kinds of knowledge that linguists, philosophers, psychologists, and anthropologists have proposed that are relevant for our present concerns. I give a definition of dark matter, its major divisions into unspoken and ineffable, and how it is distinct from other types of knowledge, including tacit knowledge. We look at knowledge-how vs. knowledge-that, for example, arguing, along with others, that no clear dividing line exists between such knowledges.

In this regard, I also discuss knowledge as “particle, wave, and field,” borrowing these three perspectives from the work of Kenneth Pike. I look at linguistic knowledge of sound units—phonemes and allophones (the local variants of phonemes)—in order to exemplify these epistemological perspectives.

Next we move to a discussion of the Platonic tradition of innate knowledge, continuing from Plato to Chomsky and beyond, via many others. This section also looks closely at the influence of the thesis of the “psychic unity of mankind” first proposed by Adolf Bastian. Following this, we survey different works in the Aristotelian tradition of dark matter. We then reach the conclusion of this chapter, also providing a survey of the major lessons learned here.

Kinds of Knowledge

As we have seen, over the last few decades, the two biggest proponents of tacit knowledge have arguably been Michael Polanyi and Noam Chomsky, though with radically different conceptions of the nature and source of this knowledge. Chomsky’s conception of tacit knowledge descends from Plato; Polanyi falls closer to Aristotle’s ideas. In contemporary research, forms of the debate over tacit knowledge are to be found in the contrasts between evolutionary psychology vs. embodied cognition, questions about whether computers can replicate human cognition in any significant sense, on the nature of concepts (what does it mean to hold a concept), in translation theory, expert systems, the assumptions that drive business decisions, the behavior of populations vs. individuals, and so on. The belief that humans share basic concepts and other knowledge innately has been a popular one in the history of Western thinking. Some of the more prominent examples beyond the two just mentioned include Freud’s notion of the unconscious forces that drive human psychology; Jung’s theory of “collective unconsciousness”; Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth”; the work of Cosmides, Tooby, and Pinker in evolutionary psychology; and Jerry Fodor’s work on mental modules.

I want to argue, to the contrary, that humans are designed to be flexible, that “human nature”—when characterized as inborn cortical, hardwired information, and instincts—is incompatible with flexibility. Humans adapt as well as upright primates might be expected to have done in the world in which they live. We are able to vary behaviors in similar environments and to respond effectively to environmental change, in the sense that their psychologies and cultures can solve problems of various types encountered by the species worldwide. Cultures are evolution’s ultimate solution to the problem of providing adaptive flexibility—so much so that the most important cognitive question, as others have put it, becomes not “What is in the brain?” but “What (culture/society/environment) is the brain in?”

Our minds and our cultures are constructed symbiotically. The relationship between culture and psychology is not supervenience, though each influences, shapes, and enhances the other. Because of this I want to argue here that nativist ideas are for the most part superfluous in understanding human cognition, once we recognize the universal platforms of human cognition, the nature of the tasks humans have to perform, and the ways in which humans “live culturally” and come to acquire the dark matter of their minds, which ultimately shapes who they are as well as how they think about and relate to the world around them.

The flexibility and cognitive resources of humans are found particularly in the dark matter of our minds—the tacit knowledge we acquire from lived experience. This knowledge comes from many sources. Culture, or “culturing,” is but one of those. Material environment is another. The nature of the task another. But the role of culture in domains where it was once considered irrelevant is vital to the understanding of ourselves and our species.

The knowledge I am concerned most with is any knowledge-how or any knowledge-that that is unsaid in normal circumstances, unarticulated even to ourselves or, at the extreme, ineffable (Levinson and Majid 2014). It comes from personal observation and social expectations (standards, values, and so on). It is shared and it is simultaneously personal. It is acquired via emicization and apperceptions. The sense of self is just these plus memory.

Variation is where the action is at in understanding ourselves, our conspecifics, and our species as a whole. We should not be too quick to look for the invariant, the abstract generalizations. We should first attempt to fully describe (Geertz 1973) and reflect on the particular (James [1906] 1996). And variation operates at multiple levels simultaneously. The two broad intersection planes of variation that concern us here are individual psychology and group culture.

Another crucial idea is that human cognition and behavior are not law-like. When we attempt to understand human cognition and human actions, we are not doing physics. We do not expect exceptionless laws. We expect rather a confluence of dynamic, shifting properties. Answers will not be simple many times and they will focus as much on variation, if not more so, than they will on constancy. I am less interested in universals and more in understanding, and I do not believe that the former is always the basis of the latter.

In fact it seems that understanding is often list-like and descriptive, rather than abstract and general (see James [1906] 1996 as well as Fodor’s (1998, 40ff) lexical semantics). The best way to judge the success of our proposals is their consonance with what we know more generally about the world, and the inclusivity and utility for those trying to deepen their understanding of the cognitive life of Homo sapiens.

I am certainly not the first to develop the thesis that nurture is at least as important as nature in understanding the thought and behavior of humans and other animals. Among the books that take on this subject from different angles are Paul Ehrlich’s (2001) Human Natures (biology); Alison Gopnik’s (2010) The Philosophical Baby (child development); Jesse Prinz’s (2014) Beyond Human Nature (philosophy), and Philip Lieberman’s (2013) The Unpredictable Species (neuroscience and linguistics). But the approach to the issue of human nature and knowledge is different here. First, it is based on anthropological and linguistic field research on some highly interesting and distinctly un-Western cultures. Second, a major—and unique—concern of this study is a new understanding of culture, and the interaction of culture with individual psychology. This interaction, as mentioned, is referred to in this work as “emicization,” borrowed from Pike (1967).

For convenience, let’s repeat the earlier definition of dark matter:

Dark matter of the mind is any knowledge-how or any knowledge-that that is unspoken in normal circumstances, usually unarticulated even to ourselves. It may be, but is not necessarily, ineffable. It emerges from acting, “languaging,” and “culturing” as we learn conventions and knowledge organization, and adopt value properties and orderings. It is shared and it is personal. It comes via emicization, apperceptions, and memory, and thereby produces our sense of “self.”

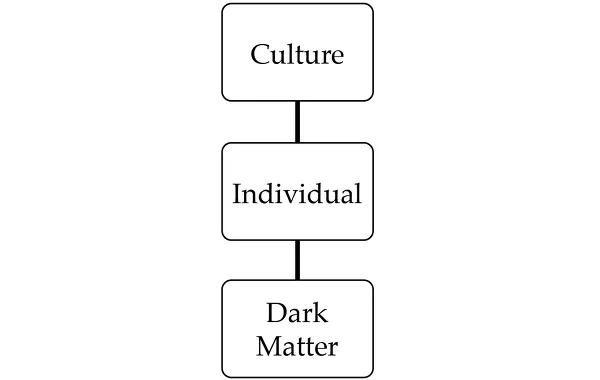

Since the literature is already rich with discussions of the unconscious, culture, and tacit knowledge, I offer figures 1.1 and 1.2 as a way of understanding how dark matter is different. Dark matter is a combination of culture and individual psychology, produced by the culturing of the individual as well as the individual’s apperceptions, interpretations of others, and personal psychology. The basic theses to be explored in regard to this idea include the following: First, we experience the world culturally, in a specific temporal-geographical-axiological context. Second, we slot our experiences into a “cultural field” or “table,” a matrix of values and knowledges that establishes the relationships of experiences to one another hierarchically and which is vital to our emerging sense of self and belonging. I call this (see chap. 2) C(ultural)-grammar.1 Third, we interpret our experiences individually and jointly, based on the cultural concepts that we have internalized. Fourth, we employ episodic memory consolidation and reconsolidation to form our complete autobiographical memory and thus our identities.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

As an attempt to illustrate the latter points, let’s consider the components of bike riding, from learning to mastery. Ryle ([1949] 2002) distinguished between “knowing-how” and “knowing-that.” As Polanyi ([1966] 2009) interprets Ryle, knowing-how consists in the ability to act. This ability, so it is claimed, cannot be made fully explicit. As Polanyi (ibid.) observes for bike riding, we acquire knowledge-how by doing something. Explicit instructions are less useful than examples.

Many philosophers, psychologists, physiologists, and others have written on knowing-how. Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger, and Nietzsche are but three of the more prominent philosophers who have discussed what it is to know how to do something. Gestalt psychologists have also written about the whole of a learned action being greater than the sum of its parts. For example, skiing is not merely moving your knee one way or the other, holding your body in a certain position, and so on. Rather, it is learing to “flow” with the act of skiing. In Pike’s terms, an action has more than a static existence; it also has dynamic existence (how it is performed) as well as “field” existence (how it relates to other actions within a given cultural system).

For any knowing-how, there exists a process to be mastered, mainly by doing, usually learned in parts. Riding a bike entails learning to mount, pedal, steer, turn, dismount, brake, and so on, without falling. We cannot learn such things by reading about them or being lectured about them. We need (painful) practice, and we benefit from examples (partially due to mirror neurons that communicate with our muscles so as to prepare them to act as we perceive another’s action).

Over time, our basal ganglia, synaptic connections, even our muscles—through specific patterns of use and excitation, even creating new fiber nuclei in some cases (Bruusgaard et al. 2010)—register these actions. We build up such memories by integrating individual apperceptions of parts of action into a whole. Then we have mastered bike riding. It has become an emic action rather than merely etic actions. The involvement of the muscles, nerves, and the body more generally, along with the seeming irrelevance of propositional knowledge, make bike riding a prototypical case of knowledge-how—the kind of knowledge one more effectively “demonstrates” than “tells.”

But are these ingredients completely lacking from what is referred to as knowledge-that? Consider a simple proposition such has “John knows that an apple is a fruit.” How can we determine whether John in fact knows the fruity nature of apples? We can only know it by what assertions he makes, how he responds to an apple in his environment, how he infers properties of the apple based on his knowledge and so on. And another question: Then how has John acquired this knowledge of apples? In just the same way, by doing and watching actions done. As John acts, he affects his synapses, his body (e.g., salivation, olfactory sense, hunger pangs), and his physiology and cognitive states more generally. In other words, to say that John knows x, we have to also know how John reacts to x, uses x in a sentence, draws inferences from x, and the like. We must know how John knows how to do these things. Yet if this is so, then the knowledge-how vs. knowledge-that distinction is at best weak, at worst nonexistent.

There is another sense in which the distinction between knowing-how and knowing-that is weak. Knowledge-how can be translated into knowledge-that. It is possible (and often done), for example, to develop a bike-riding algorithm that can enable a machine to try to ride a bike.2

When I began to learn to ride a bike, I remember focusing during each attempt on what I thought were the important steps—from my intentionally white-knuckled grip on the bar, to keeping up the minimum speed necessary to maintain forward motion without risking a lurch into the intersection, to avoiding objects by focusing ahead sufficiently to plan my steering. Conscious concentration on every subroutine of the larger act of “riding” tired me out. But as I internalized my knowledge by use of my body, before long, I “got it”—my brain’s system of equilibrioception adjusted to this new form of locomotion, and I came to “know how” to ride a bike. Riding a bike is a paradigm example of knowing-how. But is this knowing-how utterly distinct from knowing-that? To answer this question, let’s consider another problem that seems superficially like knowing-how: the knowledge of a linguistic sound system, a phonology. The phonological knowledge of native speakers is both knowing-how and knowing-that simultaneously. Before looking at phonology, however, we need to better understand “knowing-that.”

Knowing-that is generally assumed to be quite different from knowing-how. The former is propositional knowledge, while the latter encompasses skills. Thus knowing-how is taken by some philosophers and psychologists not to be knowledge at all but only habits, skills, or capacities developed over time through practice, or repetition and imitation—muscle memory, largely—whereas knowing-that is taken to be part of cognition proper. Knowing how to ride a bike, again, in this view, is not properly speaking cognition, but merely muscle routines. And yet if knowing that a proposition means x requires that we know how to use it in x-related inferences, as Brandom (1998) urges, then the how/that distinction is again weakened, if not eliminated.

Because there is a clear sense in which I have “internalized” or “emicized” the bike riding process, yet I am nevertheless unable to give a fully adequate explicit description of what I am doing when so engaged, it may not be possible to reduce knowing-how to knowing-that. There is some part of all knowledge that is not reducible to propositions. But you might reply “It has already been demonstrated that we can devise a set of algorithms for bike riding that, when fed into a robot, enables it to actually ride a bike. Wouldn’t that prove that bike riding is ultimately a knowing-that rather than a knowing-how, and thus that knowledge is not ineffable in principle?”

No. And for largely the same reason that Google Translate cannot be said to speak a language or Searle’s (1980b) “Chinese room” cannot be said to speak Chinese.3 Whatever algorithm the robot is following, I am not using these algorithms to ride my bike. How do I know? I know first because they are never conscious, and they are impossible to make conscious for the average bike rider. Second, no scan or other image of my brain is going to turn them up. They are literally not in my brain. But third and most important, the algorithms add nothing to our understanding of human bike riding. The way to understand that is to study the human body and learn what the muscles do, how the brain controls them in bike riding, and how the entire body adjusts to angles, wind, and so on, to maintain balance, speed, and directedness without overt commands. We do not linguistically represent all problems; we “resonate” with many of them (Gibson 1966, 1979). Our bodies adjust to the movement of the bike, the contour of the earth, the holes in the pavement, and so on. Perhaps the notion of resonance might even help us to understand why trying to make what we are doing explicit while ridin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1 Dark Matter and Culture

- Part 2 Dark Matter and Language

- Part 3 Implications

- Notes

- References

- Index