- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

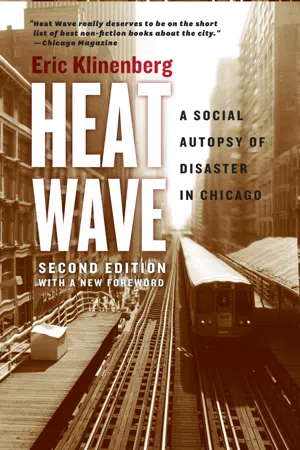

About this book

"A classic. I can't recommend it enough."--Chris Hayes

On Thursday, July 13, 1995, Chicagoans awoke to a blistering day in which the temperature would reach 106 degrees. The heat index, which measures how the temperature actually feels on the body, would hit 126 degrees by the time the day was over. Meteorologists had been warning residents about a two-day heat wave, but these temperatures did not end that soon. When the heat wave broke a week later, city streets had buckled; the records for electrical use were shattered; and power grids had failed, leaving residents without electricity for up to two days. And by July 20, over seven hundred people had perished-more than twice the number that died in the Chicago Fire of 1871, twenty times the number of those struck by Hurricane Andrew in 1992—in the great Chicago heat wave, one of the deadliest in American history.

Heat waves in the United States kill more people during a typical year than all other natural disasters combined. Until now, no one could explain either the overwhelming number or the heartbreaking manner of the deaths resulting from the 1995 Chicago heat wave. Meteorologists and medical scientists have been unable to account for the scale of the trauma, and political officials have puzzled over the sources of the city's vulnerability. In Heat Wave, Eric Klinenberg takes us inside the anatomy of the metropolis to conduct what he calls a "social autopsy," examining the social, political, and institutional organs of the city that made this urban disaster so much worse than it ought to have been.

Starting with the question of why so many people died at home alone, Klinenberg investigates why some neighborhoods experienced greater mortality than others, how the city government responded to the crisis, and how journalists, scientists, and public officials reported on and explained these events. Through a combination of years of fieldwork, extensive interviews, and archival research, Klinenberg uncovers how a number of surprising and unsettling forms of social breakdown—including the literal and social isolation of seniors, the institutional abandonment of poor neighborhoods, and the retrenchment of public assistance programs—contributed to the high fatality rates. The human catastrophe, he argues, cannot simply be blamed on the failures of any particular individuals or organizations. For when hundreds of people die behind locked doors and sealed windows, out of contact with friends, family, community groups, and public agencies, everyone is implicated in their demise.

As Klinenberg demonstrates in this incisive and gripping account of the contemporary urban condition, the widening cracks in the social foundations of American cities that the 1995 Chicago heat wave made visible have by no means subsided as the temperatures returned to normal. The forces that affected Chicago so disastrously remain in play in America's cities, and we ignore them at our peril.

For the Second Edition Klinenberg has added a new Preface showing how climate change has made extreme weather events in urban centers a major challenge for cities and nations across our planet, one that will require commitment to climate-proofing changes to infrastructure rather than just relief responses.

On Thursday, July 13, 1995, Chicagoans awoke to a blistering day in which the temperature would reach 106 degrees. The heat index, which measures how the temperature actually feels on the body, would hit 126 degrees by the time the day was over. Meteorologists had been warning residents about a two-day heat wave, but these temperatures did not end that soon. When the heat wave broke a week later, city streets had buckled; the records for electrical use were shattered; and power grids had failed, leaving residents without electricity for up to two days. And by July 20, over seven hundred people had perished-more than twice the number that died in the Chicago Fire of 1871, twenty times the number of those struck by Hurricane Andrew in 1992—in the great Chicago heat wave, one of the deadliest in American history.

Heat waves in the United States kill more people during a typical year than all other natural disasters combined. Until now, no one could explain either the overwhelming number or the heartbreaking manner of the deaths resulting from the 1995 Chicago heat wave. Meteorologists and medical scientists have been unable to account for the scale of the trauma, and political officials have puzzled over the sources of the city's vulnerability. In Heat Wave, Eric Klinenberg takes us inside the anatomy of the metropolis to conduct what he calls a "social autopsy," examining the social, political, and institutional organs of the city that made this urban disaster so much worse than it ought to have been.

Starting with the question of why so many people died at home alone, Klinenberg investigates why some neighborhoods experienced greater mortality than others, how the city government responded to the crisis, and how journalists, scientists, and public officials reported on and explained these events. Through a combination of years of fieldwork, extensive interviews, and archival research, Klinenberg uncovers how a number of surprising and unsettling forms of social breakdown—including the literal and social isolation of seniors, the institutional abandonment of poor neighborhoods, and the retrenchment of public assistance programs—contributed to the high fatality rates. The human catastrophe, he argues, cannot simply be blamed on the failures of any particular individuals or organizations. For when hundreds of people die behind locked doors and sealed windows, out of contact with friends, family, community groups, and public agencies, everyone is implicated in their demise.

As Klinenberg demonstrates in this incisive and gripping account of the contemporary urban condition, the widening cracks in the social foundations of American cities that the 1995 Chicago heat wave made visible have by no means subsided as the temperatures returned to normal. The forces that affected Chicago so disastrously remain in play in America's cities, and we ignore them at our peril.

For the Second Edition Klinenberg has added a new Preface showing how climate change has made extreme weather events in urban centers a major challenge for cities and nations across our planet, one that will require commitment to climate-proofing changes to infrastructure rather than just relief responses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heat Wave by Eric Klinenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Nordamerikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Dying Alone

The Social Production of Isolation

At the end of summer in the year 2000 I had my most personal encounter with the heat wave victims. They had been dead for five years by then, so it was hardly a typical meeting. But a generous invitation from a group of county employees who make their living working in what they call the “secret city of people who live and die alone” made the unlikely introduction possible. A few weeks before, I had read an article that reported an increase in the prevalence of dying alone in San Francisco, a city that has a far smaller population of poor and elderly residents than Chicago. In the first six months of the new year, San Francisco officials discovered almost as many cases of solitary decedents as they had during the previous decade. “More people are dying alone, with no one to arrange their funerals, settle their estates or mourn their passing,” the story explains. “Sometimes the bodies lie for months in the city morgue as officials search for heirs.”1 In San Francisco, the article continues, the public administrators office is in charge of these investigations, and stores the personal papers of solitary decedents for five years in case someone comes to collect them. This article was published close to the fifth anniversary of the 1995 heat wave in Chicago, and I wondered if the Office of the Cook County Public Administrator might have records of the cases it investigated during the disaster. One phone call later, I learned that the county had, in fact, maintained its files from the catastrophe and catalogued its work through the 1990s. Officials there had conducted roughly 1,000 to 1,200 investigations—about 3 per day—for almost every year during the 1990s. In the 1997–98 budgetary year, though, the total jumped to 1,370; and in 1998–99, the most recent year for which there were data, it was 1,562. That day I wrote to the office requesting permission to examine the files.

Soon after, I was sitting in a conference room on the twenty-sixth floor of the County Building, surrounded by roughly 160 official reports and boxes full of the mundane belongings—watches, wallets, letters, tax returns, photographs, and record books—that had been in the homes or on the persons of the heat wave victims. During the previous five years of my investigation I had spoken to neighbors, friends, and family members of some of the decedents; immersed myself in neighborhoods that had exceptional heat wave mortality rates; visited the apartment buildings and transient hotels where people had died; spent hours in the morgue looking over death certificates and speaking with the Chief Medical Examiner; scoured police reports, public health documents, and epidemiological studies; read hundreds of news articles; viewed dozens of television stories; and interviewed paramedics, police officers, and hospital workers who handled the dead and the dying the week of the heat wave. Yet nothing apart the decedents’ files had given me such an intimate and human view of the people whose isolation knew no limits, of the nature of life and death inside the sealed room.

The public administrators’ descriptions of the rooms are incisive but curt, with simple, abbreviated terms summing up the destitution surrounding most victims: “Furnished room,” many reports began, revealing the large concentrations of death in the city’s single room occupancy (SRO) dwellings; “roach infested,” and “complete mess” were common too. Most files contained instant photographs of the apartments taken by the investigators; some showed barren spaces and few signs of life, while others were so cluttered with objects as to suggest that the material goods had replaced human company in the worlds of the isolates.2 The victims’ mementos and photographs capturing better times provided some relief from the terrible images everywhere else in the files. One man, for example, died alongside a certificate awarding him the Bronze Star for exemplary conduct in ground combat during World War Two, and two photographs of himself as a handsome young soldier in full uniform. There is, however, a disturbing side to such signs of vitality and success: they show how fleeting can be one’s security, how deep are the crevices in the city, and how invisible are those who fall through the gaps.

The personal letters express the longings born of solitude, hinting at the extent to which the victims suffered from their social deprivation. Several weeks before the heat wave, one resident of an SRO dwelling in the North Side’s Uptown neighborhood penned a plea for companionship to an estranged friend in a nearby suburb, but ultimately kept the note himself. “When you have time please come visit me soon at my place,” he wrote. “I would like to see you if that’s possible, when you come to the city. Write when you can. I will be glad to hear from you.” Another resident who died in the same hotel had received a letter from a distant relative shortly before July. The writer anticipated his family’s demise, though his relative in the Chicago SRO was only fifty-three years old. “I don’t have words to tell you how bad I feel about the troubles and sickness you are having,” he began. “It seems to me that our family should have gotten along and been friends. As we near our end it seems it should be different.”

While researching the heat wave I had become familiar with a series of popular books and scholarly publications that downplayed the difficulties of living alone, especially in old age, and enthusiastically celebrated the successes of people who managed to enrich their lives and build communities while living by themselves. Renowned writers such as Robert Coles, Arlie Hochschild, and Barbara Meyerhoff had published beautiful and influential books about the capacity of older people to flourish despite their separation from family and old friends; and even Robert Putnam, whose lament over the increase in Americans bowling alone captivated the public during the 1990s, emphasized that, relative to other groups, retired senior citizens were the nation’s most active joiners. Yet none of the authors who celebrated the flourishing elderly living on their own established whether the subjects of their studies were typical or exceptional. Hochschild, in fact, had argued that her subjects were interesting precisely because they were not representative of most seniors, while the others had simply avoided the question.3 The books had done the important work of illustrating the conditions under which it is possible to age well, but they said little about the fate of the people deprived of such opportunities. Older people who live as shut-ins and isolates are no more typical than the seniors who appear in these popular texts—but their absence in the literature leaves a knowledge gap that the Public Administrator’s files help to fill.

Coles, whose book Old and On Their Own is the most recent of these works and the only one to focus on senior citizens living alone, produced a heartwarming collection of photographic and written portrayals of older Americans. Their success, as he describes it, is that they manage to “hold on—to maintain considerably more than a semblance of their privacy, their independence, their personal sovereignty, their ‘home rule’” while living alone.4 Coles presents the faces and stories of the seniors who are struggling to get through the daily challenges of aging alone but who, in the end, are making it. They manage, as one eloquently puts it, to “duck . . . bullets” such as bodily decline, boredom, depression, loneliness, illness, immobility, loss, and the constant proximity of death that come at the end of life. Neither Coles nor his informants hide the difficulties of aging alone, yet the portraits in Old and On Their Own offer few glimpses into the social universe apparent everywhere in the biographies at the Public Administrators Office. It was as if the stories of the most isolated and vulnerable seniors had been excised because they disrupted the triumphant tone of the book; they were, perhaps, too difficult to absorb.

Perhaps Coles and the photographers excluded the most difficult cases from their presentation, invoking them only as absences, ghosts we dare not see. Longevity means forging new opportunities for creating things, for making or developing meaningful relationships, for contributing to society, to family, and to friends, and it would be misleading to emphasize only the dangerous consequences of aging alone or the unusual problems of being isolated. Yet it is equally misleading to celebrate a long duration of life without thinking seriously about the quality of that life, or to let the successes of the fortunate seniors who age alone and well blind us to the difficulties of those who suffer the more severe consequences of spending most of their time by themselves.

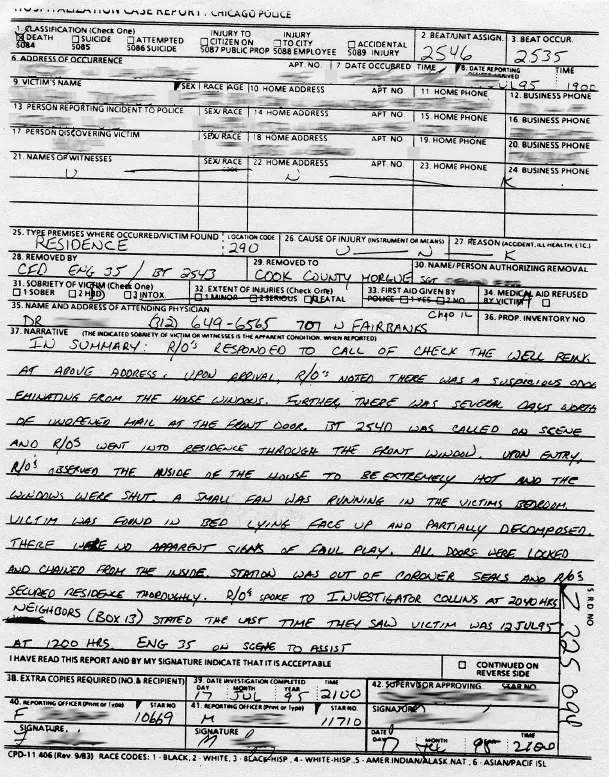

The incongruity between the accounts featured in Old and On Their Own and the Chicago stories I was learning about became even more noticeable when I discovered the police reports of the heat wave deaths. Filed in the recesses of the Cook County Morgue, the hastily scribbled notes authored by Chicago police officers show that the circumstances under which many heat victims died only emphasized the isolation and indignity of their lives.

MALE, AGE 65, BLACK, JULY 16, 1995

R/Os [responding officers] discovered the door to apt. locked from the inside by means of door chain. No response to any knocks or calls. R/Os . . . gained entry by cutting chain. R/Os discovered victim lying on his back in rear bedroom on the floor. [Neighbor] last spoke with victim on 13 July 95. Residents had not seen victim recently. Victim was in full rigor mortis. R/Os unable to locate the whereabouts of victim’s relatives.

FEMALE, AGE 73, WHITE, JULY 17, 1995

A recluse for 10 yrs, never left apartment, found today by son, apparently DOA. Conditions in apartment when R/O’s arrived thermostat was registering over 90 degrees f. with no air circulation except for windows opened by son (after death). Possible heat-related death. Had a known heart problem 10 yrs ago but never completed medication or treatment.

MALE, AGE 54, WHITE, JULY 16, 1995

R/O learned . . . that victim had been dead for quite awhile. . . .Unable to contact any next of kin. Victim’s room was uncomfortable warm. Victim was diabetic, doctor unk. Victim has daughter . . . last name unk. Victim hadn’t seen her in years. . . . Body removed to C.C.M. [Cook County Morgue]

MALE, AGE 79, BLACK, JULY 19, 1995

Victim did not respond to phone calls or knocks on victim’s door since Sunday, 16 July 95. Victim was known as quiet, to himself and at times, not to answer the door. Landlord . . . does not have any information to any relatives to victim. . . . Chain was on door. R/O was able to see victim on sofa with flies on victim and a very strong odor decay (decompose). R/Ocut chain, per permission of [landlord], called M.E. [medical examiner] who authorized removal. . . . No known relatives at this time.

These accounts rarely say enough about a victim’s death to fill a page, yet the words used to describe the deceased—“recluse,” “to himself,” “no known relatives”—and the conditions in which they were found—“chain was on door,” “no air circulation,” “flies on victim,” “decompose”—are brutally succinct testaments to the forms of abandonment, withdrawal, and isolation that proved so dangerous and extensive in Chicago during the heat wave (compare with fig. 15). Yet, like the Public Administrators Office reports, they introduce more questions about the lives inside the rooms than they resolve.

This chapter addresses the first layer of the heat wave puzzle by assembling an account of the collective production of individual-level isolation. Two questions guide this inquiry. First, why did so many hundreds of Chicagoans die alone during the heat wave? Second, to extend the question outward from the heat wave to the present, why do so many Chicagoans, particularly older residents, live alone, with limited social contacts and weak support networks during normal times?

These questions carry significant social and symbolic meaning. Most contemporary versions of the “good death” in the United States emphasize that the dying process should take place at home, a familiar setting in which the person is more likely to be comfortable. But it is even more crucial that the process is collective, shared with a community of attendant family and friends. When someone dies alone and at home, such a death can be a powerful sign of social abandonment and failure. The community to which the deceased belonged is likely to suffer from stigma or shame as a consequence, and often it will respond by producing redemptive accounts or enacting special rituals that reaffirm the bonds among the living.5

Figure 15. A police report notes the conditions of a decedent’s apartment: “suspicious odor,” “unopened mail,” “extremely hot,” “windows were shut.”

In the United States, the social issues of living alone or lacking close and durable communal ties are equally loaded. Despite considerable evidence that Americans are relatively active participants in social organizations and community groups, the specter of the lonely and atomized individual in the great metropolis has long haunted the national imagination. U.S. sociology is internationally distinct in that only here do studies focusing on the isolation of individuals and the crisis of community account for five of the six best-selling books in the history of the field, including texts entitled The Lonely Crowd and The Pursuit of Loneliness.6 Moreover, two of the most influential books in the last twenty years of American social science, William Julius Wilson’s The Truly Disadvantaged and Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, are based on theories that “social isolation,” broadly construed, is the fundamental cause of numerous and varied social problems. To talk about social isolation, it seems, is to touch a central nerve of U.S. intellectual culture.7

BEING ALONE

The issues of aging and dying alone are hardly limited to Chicago. The number of people living alone is rising almost everywhere in the world, making it one of the major demographic trends of the contemporary era.8 In the United States, the proportion of all households inhabited by one person (the U.S. Census Bureau’s best measure of people living alone) climbed steadily in the twentieth century, moving from roughly 7 percent in 1930 to 25 percent in 1995; and the percentage of all people who lived alone rose from 2 percent to about 10 percent in the same period. According to the Census Bureau, the total number of Americans living alone rose from 10.9 million in 1970 to 24.9 million in 1996; about 10 million of these, more than 40 percent of the total, are aged 65 years or older.9 As figures 16 and 17 show, the proportion of American households inhabited by only one person and the proportion of elderly people living alone has soared since 1950. These numbers are certain to rise even more in the coming decades, yet few studies document the daily routines and practices of people who live alone in their final years, and we know little about the experiential makeup of their conditions.10 We know even less about the fastest emerging group of seniors: “very old” people aged 85 years or above who live alone, often surviving the departure of their children, the death of their spouse, and the demise of their social networks.

It is important to make distinctions among living alone, being isolated, being reclusive, and being lonely. I define living alone as residing without other people in a household; being isolated as having limited social ties; being reclusive as largely confining oneself to the household; and being lonely as the subjective state of feeling alone.11 Most people who live alone, seniors included, are neither lonely nor deprived of social contacts. This is significant, because seniors who are embedded in active social networks tend to have better health and greater longevity than those who are relatively isolated. Being isolated or reclusive, then, has more negative consequences than simply living alone. But older people who live alone are more likely than seniors who live with others to be depressed, isolated, impoverishe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Prologue: The Urban Inferno

- Introduction: The City of Extremes

- Chapter One: Dying Alone: The Social Production of Isolation

- Chapter Two: Race, Place, and Vulnerability: Urban Neighborhoods and the Ecology of Support

- Chapter Three: The State of Disaster: City Services in the Empowerment Era

- Chapter Four: Governing by Public Relations

- Chapter Five: The Spectacular City: News Organizations and the Representation of Catastrophe

- Conclusion: Emerging Dangers in the Urban Environment

- Epilogue: Together in the End

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index